полная версия

полная версияEverything Begins In Childhood

Mama worked two shifts at the factory. The first one started at eight in the morning. In order not to be late for work, Mama would take Emma and me to the kindergarten very early, around six o’clock. It was winter so we arrived when it was still dark, and we paced around in the snow for an hour or an hour and a half in front of the locked building. There was a lot of snow that winter. It sparkled beautifully, streaked with silver when the moon was out. And the moon was also very beautiful and very, very big. It seemed so close that we could touch it with our hands.

We weren’t scared because we were together, but we often ended up with wet feet, and our teachers had to change our clothes.

Chapter 12. Guncha

For as long as I can remember, I knew my mama was a seamstress. “Quota,” “output,” and “plan” were among the first words I remember. Mama would mutter them angrily. I heard familiar words in Chirchik because Mama also worked at the Guncha sewing factory there. However, Mama spoke about her work with less irritation than before. Something had changed. Of course, I didn’t understand what. I was too little to understand production processes and relations. I grew to understand that much later. As a child, all I had were impressions. One memory that stuck in my mind was once when Mama took Emma and me to the factory where she worked.

Our kindergarten was closed for a quarantine that day. Mama had been at home that morning, and as she was getting ready to leave for her night shift, she said, “You can’t stay home alone. You’ll be better off sleeping overnight at the factory.”

We took a long ride on a bus. It puffed heavily and let out a roar as it went up hills. There were many of them. The twisting road ran now up, now down, and new four-story apartment buildings crowded together, some on top of hills, others at their feet. Some of the buildings still had scaffolding. The fourth micro-district – that was what this part of town was called – was under construction and growing. That was where Mama’s factory was located.

Cool air embraced us as we entered the wide lobby. A large chandelier sparkled on the ceiling. There were many bright posters on the walls. Among them, there was a board crowned with red letters that had photographs on it. Suddenly, I noticed Mama on one of them. I stopped and grabbed her by the sleeve, “Mom, what is it?”

“It’s the board of honor.” She laughed, but her face had a contented look.

We approached a door with a glass plaque. Mama adjusted Emma’s dress and knocked on the door. “We’ll be seeing the manager. Say hello to him,” she whispered.

The manager wasn’t scary at all. He called us bogatirs (Russian epic heroes), but when Mama asked his permission for us to stay in the workshop overnight, he waved his hands, “Oh no, Ester, we can’t do that,” but, when he saw that Mama was upset, he grunted and ordered, “Put them on a pile of rags in the corner, away from the machines. Got it? And they shouldn’t run around.”

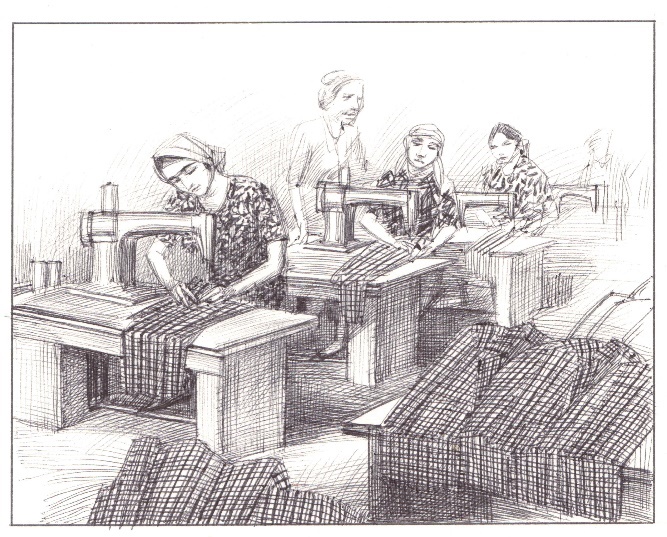

We walked up the steps leading to the workshop. Something upstairs was rumbling and chirping and rolling loudly. It seemed that something swift and huge might dash out onto the staircase toward us. It was the sewing workshop that was making all that noise. It was crammed with sewing machines, 20-30 of them in each row. It took my breath away – there were so many of them there. The foot pedal Zinger sewing machines seemed so splendid to me. The shift began, and Mama sat down at one of those wonderful machines.

Guncha was a knitting factory, and they mostly made knitted jackets there. So, what was actually being sewn? Making the jackets included many operations, from cutting them out to sewing on buttons: many short, clearly delineated, strictly limited operations that didn’t require any imagination but demanded precision and concentration and didn’t allow for any minor deviations.

The team in which Mama worked attached collars. That operation was divided into a few stages. Mama performed the first stage – she had to attach the middle of the lower part of the collar to the back of a jacket’s collar line, right in the middle. Everything else was based on that first positioning. If Mama made a mistake, the whole jacket would be ruined, and it would be classified as defective merchandise.

Someone brought a cart piled with jackets to the end of the row. Mama snatched a jacket and a collar. Oone, and a jacket flew into the machine. Twoo, Mama turned it so fast with her hands that I didn’t even notice its color. And I didn’t notice how the collar ended up in the right spot. Thrree, it was done, and the jacket flew on to the next seamstress… Mama’s machine was chipping and chirping. She sat with her head down, rocking slightly. Her feet moved without stopping, her hands made fast, precise movements. She was absorbed in her work. It seemed she didn’t notice either the rumbling of the workshop, the rattling of carts passing by, or her children who sat in the corner on a pile of multi-colored scraps watching her… Well, I was the only one who was watching Mama. The pile of bright, soft scraps was a real treasure that any girl would have envied. It was hard to imagine that such treasure was considered trash at the factory. Emma rummaged through the scraps, mumbling something, snatching and twisting them, tying them together, trying them on. She made a scarf, a shawl, or something that looked like a harlequin’s outfit. In a word, she was very busy.

But I could not tear my eyes away from the assembly line. I watched how fast the jackets moved along it, but my eyes always returned to Mama’s machine, to her hands. And what I soon noticed was that Mama was working faster than the others. She would pass a jacket to the next seamstress, who had not yet finished with the previous one. Someone called from another part of the workshop, “Ester, take a break! Slow down!” But Mama seemed not to hear; she didn’t raise her head.

Mama was a wonderful seamstress, a virtuoso. She couldn’t possibly do bad work.

But that was not the only reason. At Guncha, unlike at the factory in Tashkent, they paid according to one’s output. Mama’s earnings depended on her hands, on her craftsmanship. Mama’s restless hands kept Emma and me fed.

Only here in Chirchik, Mama felt that her work was valued. Before long, she was awarded the Order of Labor of the Third Degree. Only five people in town had received that award. Mama was certainly proud of it. Perhaps, she was even very proud. Mama’s work was exhausting, her speed, efficiency, and concentration required an enormous output of energy and produced nervous tension. Good heavens, but did she ever think of herself?

When apprentices showed up at the factory, they were taken to Mama. Who could possibly teach them better? Who could demonstrate to them more patiently, many times over, how to do the work? They sometimes brought defective items to her, and she repaired them with the skill a surgeon would use operating on a seemingly hopeless patient.

Probably, a true master in any field is one who possesses emotional generosity, as well as skill.

…The time passed, hour after hour. The workshop rumbled ceaselessly. Emma had fallen asleep long before, buried in her pile of treasure. I was falling asleep too, but I gave a start and woke up because silence fell over the workshop. A break began. I don’t know if there was a cafeteria at the factory, but many seamstresses had a snack at their machines. They plugged in their hand-held water boilers. The sound of paper rustling could be heard as they unwrapped their sandwiches. Now and then, women ran up to Emma and me to treat us to candies or cookies. They had kind, tired faces, scarves tied around their heads, wearing aprons covered with bits of thread. Then, Shura Cheremisina, our neighbor, came up to us.

“Good! You’ve brought your kids,” she told Mama. “Let them see what we do here.”

“We work like mules,” Mama’s answer was short. She sat down near us. There was a piece of thread hanging from her lower lip. Almost every seamstress had a piece of thread on her lip. It helped them concentrate while sewing. Every part of them participated in the work process – hands, feet, eyes, even lips.

Chapter 13. “Our Neighbor Is a Greek Woman…”

“Kids, get up! It’s time, it’s time!”

I opened my eyes and squinted right away. After our rather dark Tashkent bedroom, I was not accustomed to the bright light that streamed into my eyes. Here, the two big windows faced the vegetable garden in the back of our building and an expanse of open space with towering hills beyond. The sun set behind them in the evening, and in the afternoon, it visited our bedroom, flooding it generously with its rays. Mama had had bars installed on the windows so that we wouldn’t climb through them while we were busy playing.

I stayed in bed for another minute or two, admiring the bedroom. It had delicate blue walls onto which little gold striped diamonds had been rolled. When I looked at the wall for a long time, I would get the feeling I was in outer space, surrounded by stars. One could also admire the floors, which were freshly painted and almost even.

The radio was on. In the morning, Father put the radio on the windowsill in the living room so that Emma and I could do our morning exercises. We did them for fifteen minutes to the sounds of music. We enjoyed doing them and even had time to be naughty and make faces.

“Emma, can you do this?” I asked, winking each of my eyes one after the other. I was cunning. I knew perfectly well what would happen next. She couldn’t wink each eye individually, even though she had tried many times.

“No, not like that! Look!”

I pretended I was trying to help Emma. She was trying to learn how to do it but would end up exhausted from trying. Sometimes, she would run to Mama to complain.

We finished our exercises, so I washed myself quickly with cold water, got dressed and sat down at the table.

“Just a minute,” Mama said as she was slicing lettuce. “I’m about to serve breakfast. Papesh, I need to go to the bazaar today.”

“Go,” Father answered.

“How about some cash? We’ve already spent my salary.”

“I don’t have any,” Father snapped.

It was his usual answer. It had happened many times. Mama would grow quiet and run to neighbors or acquaintances to borrow money until a payday, naturally, hers.

* * *When I remember my father, when I try to imagine what kind of person he was, I envision someone with two personalities. And I wonder – which of them was actually him?

Father, like his brother Misha, was a teacher. One knows that a teacher is a model to imitate, to be held up as an example. That was exactly how the brothers were at work. They enjoyed respect. They did their best to earn it. They attained authority. They needed that for their careers. But at home they were absolutely different, as if they shed their masks. They claimed to be the sole authority and demanded respect. They were despots.

At work, the brothers were building their careers, and they yielded to the rules that facilitated that. At home, such rules were considered superfluous. Wife and children had to obey them, to tolerate everything, to forgive.

Father liked to pose as a well-off man. He didn’t like being thrifty. Why take a bus if you could take a taxi? It was so nice to toss money around, to spend it for his little pleasures, not for boring household needs. It’s true that he sometimes bought clothes, a book, or a toy for Emma and me. When he was in a particularly good mood, he would give Mama some money for shopping at the bazaar, but most of the time he answered as he did that day, “I don’t have any.” But this time Mama didn’t keep silent. I heard her quiet, tense voice:

“So, where does the money disappear to?”

Father raised his brows angrily. He wasn’t used to such questions, but an even less familiar question followed.

“If you don’t give me money for shopping, why do you eat the food I provide?” Mama asked in the same voice.

Father didn’t answer. He jumped up from the table, ran to the stove and knocked the pan with the cutlets in it onto the floor.

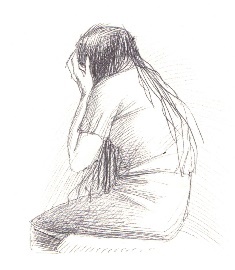

The front door banged – Father left. Mama cried, covering her face. I sat in a stupor, but my heart was pounding as if someone were hitting my chest with a hammer.

We went to the kindergarten without having eaten anything. What happened next is difficult for me to describe, for I learned about it from Mama much later. But perhaps what she told me became so strongly intertwined with my childhood impressions, with my intense feeling of pain for Mama, that sometimes it seemed to me that I didn’t spend that day at the kindergarten but instead went with Mama to the factory. There she walked, so thin, pale and unhappy, whispering, “Why me? Why me?” She had hoped that after leaving Korotky Lane and getting rid of Grandma Lisa’s spite, she would live a normal family life. But no, that didn’t happen. Grandma Lisa dogged her, like a shadow. She was nearby even now, in her son.

Here was Mama at the sewing machine. Rocking in time to its rhythm, her head lowered, she whispered something as if she were talking to her breadwinner. The machine understood her and answered sympathetically. “R-r-r!” its motor was terrified. “What for? What for?” the pedal squeaked indignantly. “Prick-prick-prick! Prick-prick-prick!” its needle hurried to the rescue. “I’ll prick him, I won’t allow him to hurt you.” Even the jacket, obedient and soft, gliding under the needle like a skater on ice, tried to ease Mama’s suffering. But her tears continued to fall onto the soft fabric.

“What’s wrong, Ester?” Katya, the seamstress who sat behind Mama, came up to her and hugged her by the shoulders. “What’s happened? Is something wrong at home?”

Mama nodded. Her story was short and muddled. On hearing it, Katya exclaimed, “Let’s go see Sonya, as soon as possible, during the break!”

Sonya, the head of the factory’s Trade Union Committee, was a sharp woman, the kind of woman whom the saying “Be on your guard when she’s around” suited well. She was compassionate. She acted decisively, using all the energy built up inside her, when she could sometimes help workers without antagonizing the management. And Mama’s misfortune afforded her just such an opportunity.

“You’re so silly, Ester. Why have you concealed it for such a long time? We’ll show him… If he doesn’t want to behave, we’ll exchange your apartment for two… It’s impermissible for a teacher to behave like that. I would understand if he were an alcoholic… All right! We’ll go to your place after work!”

Sonya had made a decision. Everything was clear to her. And Mama stood in front of her with her tear-stained face, thinking, was she really ready to flee again? What would she have done if her co-worker and friend hadn’t taken her to Sonya?

Certainly, it’s very important to know that one is not alone. Perhaps, that was the most important thing. But still… Now I think that it was a different Ester in Sonya’s office that day, not the one who humbly tolerated her husband’s cursing and beating and the insults of his relatives. Something had been building up in her and it broke through on the day she took an axe and smashed the walls of the hated house. Her first victory, moving to Chirchik, gave her strength. Was it possible that the respect she enjoyed at the factory and the fact that she was earning more had boosted her self-confidence? It must have been so…

Mama looked at Sonya.

“Yes. Let’s go after work!”

Then we were at home. We, because Mama picked us up from kindergarten on the way home. We were in our room because children should not be around when adults have serious conversations. But our door was cracked. I could see and hear everything. Mama and an unfamiliar woman were in the living room. And where was Father? He was in the bedroom, dressing hurriedly. I was quite worried, for I did understand something, after all. What would Father do? I saw him go to the front door, for some reason, with an axe in his hands, and head for the vegetable garden. He began chopping branches, as if to say, “See? I have work to do here.” But Sonya wasn’t the kind of person one could play such games with. She came out onto the veranda and began her attack.

“Comrade Yuabov, you have visitors in your house, and you’ve walked away. That’s not polite. Come on! We need to talk!”

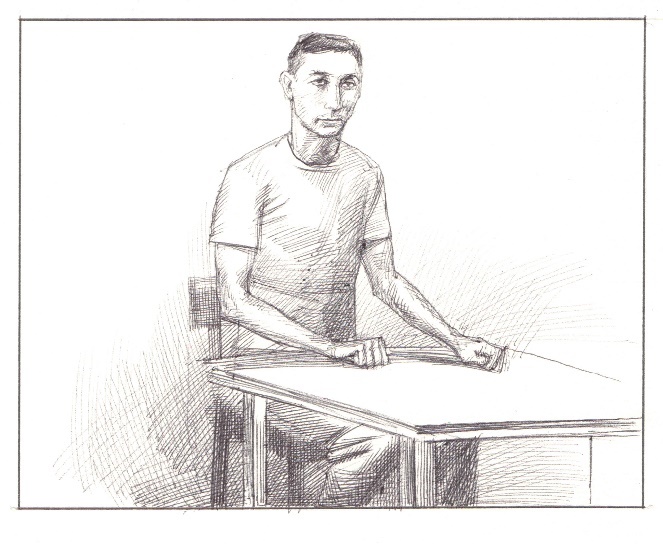

The adults sat around the table. I could see Father’s face. I had never seen him look like that. His face was pale. That I had seen often. His lips were clenched and distorted. That I had also seen – his lips were always like that when he was angry and quarreled with Grandma or Mama. His big nose, curved like an eagle’s, was close to his lips. I had seen that too. But his eyes… yes, it was precisely his eyes that changed his face, made it unfamiliar. Father stared at the visitor, and his glance betrayed his confusion and fear.

Sonya had already introduced herself. She was calm and focused. This situation was not unusual for her. She had taken part in such encounters many times. She was the one to give orders and make decisions: she and she alone. But for Father… Everything was upside down for him. Perhaps, this meeting at the table reminded him of the schoolteachers’ meetings he had attended so many times, but not in this capacity. There, he was an eagle attacking lackadaisical students. Here, Sonya was the eagle. She looked at Father, her glance icy, and asked sternly, “How can you explain what has happened?”

Father was silent, beating the table with his fingers.

“If you don’t want to live together, no one is forcing you,” Sonya continued ruthlessly. “The apartment can be split. You’ll be given a room.”

Silence.

“You’re a teacher, aren’t you?”

Father nodded as he continued beating the table with his fingers, the same grimace on his face and his legs crossed.

“So, this teacher thinks that he can humiliate, beat and harass a defenseless woman. And the school principal probably thinks he has an angel working for him… I’ll visit your principal. I’ll talk to him…”

“One…” Father began to say. He must have decided to answer. “One of our neighbors is a Greek woman…”

Sonya just looked at him in bewilderment, then she turned to Mama. What did this have to do with the neighbor? Sonya didn’t know Father’s trick. When he was cornered, he would blurt out some nonsense to confuse the person who was talking to him, pretending to be a simpleton, to shift the conversation in a different direction.

But it was impossible to confuse Sonya. Without waiting for him to continue his story about the Greek neighbor, she reminded him calmly, “I’m asking you for an answer. Do you want a divorce, or are you willing to live normally?”

“Everything’s normal with us here,” Father mumbled.

“Beating your wife, throwing food on the floor? What’s normal about that?”

Father mumbled something unintelligible again. But the visitor inflicted blow after blow, calmly and persistently breaking the P.S. 19 teacher into even smaller pieces.

Father sat there, drumming the table with his fingers. No, he wasn’t sitting at the table, he had been knocked down, defeated. Sonya was an experienced fighter. She knew that people like my father, self-confident, merciless with the weak, had to be taken by surprise and pinned down.

After casting a last stern, contemptuous glance at Father, Sonya stood up.

“All right, this conversation is over. It’s up to you to decide what will happen next.”

In the morning, my parents talked to each other. Father was calm, polite and nice. We all felt good. Mama even smiled. All was well… for a few days.

Chapter 14. The First School Bell

Finally, it was Sunday night. It lasted too long and didn’t want to make way for the long-awaited tomorrow. It would be the next day, September 1st, when the most important event would happen – I would go to school. Something utterly unimaginable was happening in my head, so nervous was I.

Any events that interrupt the usual course of life provoke nervousness in me, almost as if I were sick. My heart was beating as if it wanted to burst out of my chest. My cheeks were on fire. My fingers would always move by themselves, but I had never been so nervous as this time.

One thing that helped me cope with it, to some extent, was carefully organizing my school gear, all those new things I needed for class that I had received over the summer.

I decided that I should check one more time whether everything was all right. I wouldn’t have any time to do it in the morning. I picked up my new shirt and began to examine it. It was a nice pale-blue cotton shirt. Mama and I had spent so much time looking for a shirt. We had also spent time buying everything else – textbooks, notebooks, a briefcase. In Chirchik, just as in every other town, stores were very seldom supplied with goods. Everything sold out fast. Customers waited for the next delivery, lying in wait for weeks for the things they needed. Lines looked like huge earthworms, and people would run up to them like restless ants with questions: “What was delivered today? What are they selling?”

It’s difficult to imagine anything drearier than store shelves in between deliveries. We stopped at the bookstore and saw that it mostly carried newspapers and brochures with boring covers. As for the newspapers, they were all like members of one big family: Pravda (Truth), Komsomol Pravda, Pravda Vostoka (Truth of the East). We visited the bookstore over and over again, until finally we were rewarded – we were able to buy an ABC book. It was new and smelled pleasantly of paper, paint and glue.

After much effort, we also obtained a briefcase. I scrutinized and admired it endlessly. It smelled like a real leather briefcase. It was unimaginably shiny, and I loved the way it squeaked. It had three compartments – for textbooks, notebooks, and rulers, and a pen case. No words could express how wonderful its lock was. It clicked like a gun trigger. Hey, you out there, beware!

All the objects I had in the briefcase were splendid, particularly the white porcelain inkpot with its blue trim on the top, known as nevilevaika (non-spilling), because ink wouldn’t spill out of its cone-shaped opening, even if you turned it upside down.

Extra pen nibs in a special section of the pen case gleamed like little mirrors. I would soon have a chance to learn that their behavior could be treacherous. You would dip your pen into the inkpot and begin to write without wiping it on the edge of the opening, and… plop! You’d have an inkblot, an ugly navy-blue spider on a clean sheet of paper. There was no way to erase it with an eraser. You would only make a hole. But those treacherous pen nibs squeaked so wonderfully.

After placing all my treasures in the briefcase, I finally went to bed, but my impatience and anxiety kept me from falling asleep for a long time.

* * *Mama and I approached the school early on the morning of that sunny and cloudless day.

Construction of P.S. 24 had been completed by the time we arrived in Chirchik. It was located next to Pinocchio Kindergarten, which I had attended before. There was a short fence and a pedestrian path between them, the path that I was now symbolically crossing. By the way, I was crossing it prematurely. One was supposed to be seven to start school, and I was six. But my father had carried out an offensive operation to secure my enrollment in school ahead of time, and he had been successful.

The four-story school building glittered in its whiteness. The posters and banners seemed especially bright against the white walls. The large portrait of Lenin, with his arm outstretched, calling upon arriving students to study diligently, had been placed above the door where it was impossible to miss. The square in front of the school was filled with adults and children carrying bunches of flowers in their hands. I was glad to see familiar faces, my kindergarten friends – tall skinny Zhenya Gaag, stout Sergey Zhiltsov, and the Doronin twins, Alla and Oksana. My nervousness eased a bit when a muted but frightening voice echoed through the air: “Dear parents… you and your children… today…” I didn’t realize at first that the words were being spoken by a tall man in a dark suit standing at a microphone. He was the school principal, Vladimir Petrovich Obyedkov. He spoke for a long time. I calmed down and became distracted. Then I saw that the tall man held a pair of scissors, with which he cut a pink ribbon stretched across the entrance to the lobby. An orchestra struck up a tune. The copper of the trumpets gleamed. We were all invited to enter the school. The corridor on the ground floor, along which we were ushered to our classroom, was so long that it seemed endless. At every door I thought, my heart skipping a beat, “This one must be ours.” But the door of our classroom was the very last one.