Полная версия

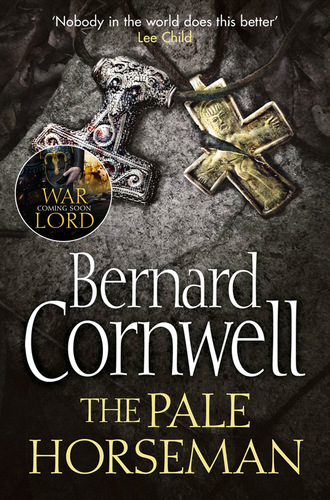

The Pale Horseman

‘That’s not what I hear.’

He looked at me suspiciously ‘And what do you hear, young man?’

‘That God has sent us peace.’

Wulfhere laughed at my mockery. ‘Guthrum’s in Gleawecestre,’ he said, ‘and that’s just a half day’s march from our frontier. And they say more Danish ships arrive every day. They’re in Lundene, they’re in the Humber, they’re in the Gewæsc.’ He scowled. ‘More ships, more men, and Alfred’s building churches! And there’s this fellow Svein.’

‘Svein?’

‘Brought his ships from Ireland. Bastard’s in Wales now, but he won’t stay there, will he? He’ll come to Wessex. And they say more Danes are joining him from Ireland.’ He brooded on this bad news. I did not know whether it was true, for such rumours were ever current, but Wulfhere plainly believed it. ‘We should march on Gleawecestre,’ he said, ‘and slaughter the lot of them before they slaughter us, but we’ve got a kingdom ruled by priests.’

That was true, I thought, just as it was certain that Wulfhere would not make it easy for me to see Ragnar. ‘Will you give a message to Ragnar?’ I asked.

‘How? I don’t speak Danish. I could ask the priest, but he’ll tell Alfred.’

‘Does Ragnar have a woman with him?’ I asked.

‘They all do.’

‘A thin girl,’ I said, ‘black hair. Face like a hawk.’

He nodded cautiously. ‘Sounds right. Has a dog, yes?’

‘She has a dog,’ I said, ‘and its name is Nihtgenga.’

He shrugged as if he did not care what the dog was called, then he understood the significance of the name. ‘An English name?’ he asked. ‘A Danish girl calls her dog Goblin?’

‘She isn’t Danish,’ I said. ‘Her name is Brida, and she’s a Saxon.’

He stared at me, then laughed. ‘The cunning little bitch. She’s been listening to us, hasn’t she?’

Brida was indeed cunning. She had been my first lover, an East Anglian girl who had been raised by Ragnar’s father and who now slept with Ragnar. ‘Talk to her,’ I said, ‘and give her my greetings, and say that if it comes to war …’ I paused, not sure what to say. There was no point in promising to do my best to rescue Ragnar, for if war came then the hostages would be slaughtered long before I could reach them.

‘If it comes to war?’ Wulfhere prompted me.

‘If it comes to war,’ I said, repeating the words he had spoken to me before my penance, ‘we’ll all be looking for a way to stay alive.’

Wulfhere stared at me for a long time and his silence told me that though I had failed to find a message for Ragnar I had given a message to Wulfhere. He drank ale. ‘So the bitch speaks English, does she?’

‘She’s a Saxon.’

As was I, but I hated Alfred and I would join Ragnar when I could, if I could, whatever Mildrith wanted, or so I thought. But deep under the earth, where the corpse serpent gnaws at the roots of Yggdrasil, the tree of life, there are three spinners. Three women who make our fate. We might believe we make choices, but in truth our lives are in the spinners’ fingers. They make our lives, and destiny is everything. The Danes know that, and even the Christians know it. Wyrd bið ful aræd, we Saxons say, fate is inexorable, and the spinners had decided my fate because, a week after the Witan had met, when Exanceaster was quiet again, they sent me a ship.

The first I knew of it was when a slave came running from Oxton’s fields saying that there was a Danish ship in the estuary of the Uisc and I pulled on boots and mail, snatched my swords from their peg, shouted for a horse to be saddled and rode to the foreshore where Heahengel rotted.

And where, standing in from the long sandspit that protects the Uisc from the greater sea, another ship approached. Her sail was furled on the long yard and her dripping oars rose and fell like wings and her long hull left a spreading wake that glittered silver under the rising sun. Her prow was high, and standing there was a man in full mail, a man with a helmet and spear, and behind me, where a few fisherfolk lived in hovels beside the mud, people were hurrying towards the hills and taking with them whatever few possessions they could snatch. I called to one of them. ‘It’s not a Dane!’

‘Lord?’

‘It’s a West Saxon ship,’ I called, though they did not believe me and hurried away with their livestock. For years they had done this. They would see a ship and they would run, for ships brought Danes and Danes brought death, but this ship had no dragon or wolf or eagle’s head on its prow. I knew the ship. It was the Eftwyrd, the best named of all Alfred’s ships which otherwise bore pious names like Heahengel or Apostol or Cristenlic. Eftwyrd meant judgement day which, though Christian in inspiration, accurately described what she had brought to many Danes.

The man in the prow waved and, for the first time since I had crawled on my knees to Alfred’s altar, my spirits lifted. It was Leofric, and then the Eftwyrd’s bows slid onto the mud and the long hull juddered to a halt. Leofric cupped his hands. ‘How deep is this mud?’

‘It’s nothing!’ I shouted back, ‘a hand’s depth, no more!’

‘Can I walk on it?’

‘Of course you can!’ I shouted back.

He jumped and, as I had known he would, sank up to his thighs in the thick black slime, and I bent over my saddle’s pommel in laughter, and the Eftwyrd’s crew laughed with me as Leofric cursed, and it took ten minutes to extricate him from the muck, by which time a score of us were plastered in the stinking stuff, but then the crew, who were mostly my old oarsmen and warriors, brought ale ashore, and bread and salted pork, and we made a midday meal beside the rising tide.

‘You’re an earsling,’ Leofric grumbled, looking at the mud clogging up the links of his mail coat.

‘I’m a bored earsling,’ I said.

‘You’re bored?’ Leofric said, ‘so are we.’ It seemed the fleet was not sailing. It had been given into the charge of a man named Burgweard who was a dull, worthy soldier whose brother was bishop of Scireburnan, and Burgweard had orders not to disturb the peace. ‘If the Danes aren’t off the coast,’ Leofric said, ‘then we aren’t.’

‘So what are you doing here?’

‘He sent us to rescue that piece of shit,’ he nodded at Heahengel. ‘He wants twelve ships again, see?’

‘I thought they were building more?’

‘They were building more, only it all stopped because some thieving bastards stole the timber while we were fighting at Cynuit, and then someone remembered Heahengel and here we are. Burgweard can’t manage with just eleven.’

‘If he isn’t sailing,’ I asked, ‘why does he want another ship?’

‘In case he has to sail,’ Leofric explained, ‘and if he does then he wants twelve. Not eleven, twelve.’

‘Twelve? Why?’

‘Because,’ Leofric paused to bite off a piece of bread, ‘because it says in the gospel book that Christ sent out his disciples two by two, and that’s how we have to go, two ships together, all holy, and if we’ve only got eleven then that means we’ve only got ten, if you follow me.’

I stared at him, not sure whether he was jesting. ‘Burgweard insists you sail two by two?’

Leofric nodded. ‘Because it says so in Father Willibald’s book.’

‘In the gospel book?’

‘That’s what Father Willibald tells us,’ Leofric said with a straight face, then saw my expression and shrugged. ‘Honest! And Alfred approves.’

‘Of course he does.’

‘And if you do what the gospel book tells you,’ Leofric said, still with a straight face, ‘then nothing can go wrong, can it?’

‘Nothing,’ I said. ‘So you’re here to rebuild Heahengel?’

‘New mast,’ Leofric said, ‘new sail, new rigging, patch up those timbers, caulk her, then tow her back to Hamtun. It could take a month!’

‘At least.’

‘And I never was much good at making things. Good at fighting, I am, and I can drink ale as well as any man, but I was never much good with a mallet and wedge or with adzes. They are.’ He nodded at a group of a dozen men who were strangers to me.

‘Who are they?’

‘Shipwrights.’

‘So they do the work?’

‘Can’t expect me to do it!’ Leofric protested. ‘I’m in command of the Eftwyrd!’

‘So,’ I said, ‘you’re planning to drink my ale and eat my food for a month while those dozen men do the work?’

‘You have any better ideas?’

I gazed at the Eftwyrd. She was a well-made ship, longer than most Danish boats and with high sides that made her a good fighting platform. ‘What did Burgweard tell you to do?’ I asked.

‘Pray,’ Leofric said sourly, ‘and help repair Heahengel.’

‘I hear there’s a new Danish leader in the Sæfern Sea,’ I said, ‘and I’d like to know if it’s true. A man called Svein. And I hear more ships are joining him from Ireland.’

‘He’s in Wales, this Svein?’

‘That’s what I hear.’

‘He’ll be coming to Wessex then,’ Leofric said.

‘If it’s true.’

‘So you’re thinking …’ Leofric said, then stopped when he realised just what I was thinking.

‘I’m thinking that it doesn’t do a ship or crew any good to sit around for a month,’ I said, ‘and I’m thinking that there might be plunder to be had in the Sæfern Sea.’

‘And if Alfred hears we’ve been fighting up there,’ Leofric said, ‘he’ll gut us.’

I nodded up river towards Exanceaster. ‘They burned a hundred Danish ships up there,’ I said, ‘and their wreckage is still on the riverbank. We should be able to find at least one dragon’s head to put on her prow.’

Leofric stared at the Eftwyrd. ‘Disguise her?’

‘Disguise her,’ I said, because if I put a dragon head on Eftwyrd no one would know she was a Saxon ship. She would be taken for a Danish boat, a sea raider, part of England’s nightmare.

Leofric smiled. ‘I don’t need orders to go on a patrol, do I?’

‘Of course not.’

‘And we haven’t fought since Cynuit,’ he said wistfully, ‘and no fighting means no plunder.’

‘What about the crew?’ I asked.

He turned and looked at them. ‘Most of them are evil bastards,’ he said, ‘they won’t mind. And they all need plunder.’

‘And between us and the Sæfern Sea,’ I said, ‘there are the Britons.’

‘And they’re all thieving bastards, the lot of them,’ Leofric said. He looked at me and grinned. ‘So if Alfred won’t go to war, we will?’

‘You have any better ideas?’ I asked.

Leofric did not answer for a long time. Instead, idly, as if he was just thinking, he tossed pebbles towards a puddle. I said nothing, just watched the small splashes, watched the pattern the fallen pebbles made, and knew he was seeking guidance from fate. The Danes cast rune sticks, we all watched for the flight of birds, we tried to hear the whispers of the gods, and Leofric was watching the pebbles fall to find his fate. The last one clicked on another and skidded off into the mud and the trail it left pointed south towards the sea. ‘No,’ he said, ‘I don’t have any better ideas.’

And I was bored no longer, because we were going to be Vikings.

We found a score of carved beasts’ heads beside the river beneath Exanceaster’s walls, all of them part of the sodden, tangled wreckage that showed where Guthrum’s fleet had been burned and we chose two of the least scorched carvings and carried them aboard Eftwyrd. Her prow and stern culminated in simple posts and we had to cut the posts down until the sockets of the two carved heads fitted. The creature at the stern, the smaller of the two, was a gape-mouthed serpent, probably intended to represent Corpse-Ripper, the monster that tore at the dead in the Danish underworld, while the beast we placed at the bow was a dragon’s head, though it was so blackened and disfigured by fire that it looked more like a horse’s head. We dug into the scorched eyes until we found unburned wood, and did the same with the open mouth and when we were finished the thing looked dramatic and fierce. ‘Looks like a fyrdraca now,’ Leofric said happily. A fire-dragon.

The Danes could always remove the dragon or beast-heads from the bows and sterns of their ships because they did not want the horrid-looking creatures to frighten the spirits of friendly land and so they only displayed the carved monsters when they were in enemy waters. We did the same, hiding our fyrdraca and serpent head in Eftwyrd’s bilges as we went back down river to where the shipwrights were beginning their work on Heahengel. We hid the beast-heads because Leofric did not want the shipwrights to know he planned mischief. ‘That one,’ he jerked his head towards a tall, lean, grey-haired man who was in charge of the work, ‘is more Christian than the Pope. He’d bleat to the local priests if he thought we were going off to fight someone, and the priests will tell Alfred and then Burgweard will take Eftwyrd away from me.’

‘You don’t like Burgweard?’

Leofric spat for answer. ‘It’s a good thing there are no Danes on the coast.’

‘He’s a coward?’

‘No coward. He just thinks God will fight the battles. We spend more time on our knees than at the oars. When you commanded the fleet we made money. Now even the rats on board are begging for crumbs.’

We had made money by capturing Danish ships and taking their plunder, and though none of us had become rich we had all possessed silver to spare. I was still wealthy enough because I had a hoard hidden at Oxton, a hoard that was the legacy of Ragnar the Elder, and a hoard that the church and Oswald’s relatives would make their own if they could, but a man can never have enough silver. Silver buys land, it buys the loyalty of warriors, it is the power of a lord, and without silver a man must bend the knee or else become a slave. The Danes led men by the lure of silver, and we were no different. If I was to be a lord, if I was to storm the walls of Bebbanburg, then I would need men and I would need a great hoard to buy the swords and shields and spears and hearts of warriors, and so we would go to sea and look for silver, though we told the shipwrights that we merely planned to patrol the coast. We shipped barrels of ale, boxes of hard-baked bread, cheeses, kegs of smoked mackerel and flitches of bacon. I told Mildrith the same story, that we would be sailing back and forth along the shores of Defnascir and Thornsæta. ‘Which is what we should be doing anyway,’ Leofric said, ‘just in case a Dane arrives.’

‘The Danes are lying low,’ I said.

Leofric nodded. ‘And when a Dane lies low you know there’s trouble coming.’

I believed he was right. Guthrum was not far from Wessex, and Svein, if he existed, was just a day’s voyage from her north coast. Alfred might believe his truce would hold and that the hostages would secure it, but I knew from my childhood how land-hungry the Danes were, and how they lusted after the lush fields and rich pastures of Wessex. They would come, and if Guthrum did not lead them then another Danish chieftain would gather ships and men and bring his swords and axes to Alfred’s kingdom. The Danes, after all, ruled the other three English kingdoms. They held my own Northumbria, they were bringing settlers to East Anglia and their language was spreading southwards through Mercia, and they would not want the last English kingdom flourishing to their south. They were like wolves, shadow-skulking for the moment, but watching a flock of sheep fatten.

I recruited eleven young men from my land and took them on board Eftwyrd, and brought Haesten too, and he was useful for he had spent much of his young life at the oars. Then, one misty morning, as the strong tide ebbed westwards, we slid Eftwyrd away from the river’s bank, rowed her past the low sandspit that guards the Uisc and so out to the long swells of the sea. The oars creaked in their leather-lined holes, the bow’s breast split the waves to shatter water white along the hull, and the steering oar fought against my touch and I felt my spirits rise to the small wind and I looked up into the pearly sky and said a prayer of thanks to Thor, Odin, Njord and Hoder.

A few small fishing boats dotted the inshore waters, but as we went south and west, away from the land, the sea emptied. I looked back at the low dun hills slashed brighter green where rivers pierced the coast, and then the green faded to grey, the land became a shadow and we were alone with the white birds crying and it was then we heaved the serpent’s head and the fyrdraca from the bilge and slotted them over the posts at stem and stern, pegged them into place and turned our bows westwards.

The Eftwyrd was no more. Now the Fyrdraca sailed, and she was hunting trouble.

Three

The crew of the Eftwyrd turned Fyrdraca had been at Cynuit with me. They were fighting men and they were offended that Odda the Younger had taken credit for a battle they had won. They had also been bored since the battle. Once in a while, Leofric told me, Burgweard exercised his fleet by taking it to sea, but most of the time they waited in Hamtun. ‘We did go fishing once, though,’ Leofric admitted.

‘Fishing?’

‘Father Willibald preached a sermon about feeding five thousand folk with two scraps of bread and a basket of herring,’ he said, ‘so Burgweard said we should take nets out and fish. He wanted to feed the town, see? Lots of hungry folk.’

‘Did you catch anything?’

‘Mackerel. Lots of mackerel.’

‘But no Danes?’

‘No Danes,’ Leofric said, ‘and no herring, only mackerel. The bastard Danes have vanished.’

We learned later that Guthrum had given orders that no Danish ships were to raid the Wessex coast and so break the truce. Alfred was to be lulled into a conviction that peace had come, and that meant there were no pirates roaming the seas between Kent and Cornwalum and their absence encouraged traders to come from the lands to the south to sell wine or to buy fleeces. The Fyrdraca took two such ships in the first four days. They were both Frankish ships, tubby in their hulls, and neither with more than six oars a side, and both believed the Fyrdraca was a Viking ship for they saw her beast-heads, and they heard Haesten and I talk Danish and they saw my arm rings. We did not kill the crews, but just stole their coins, weapons and as much of their cargo as we could carry. One ship was heaped with bales of wool, for the folk across the water prized Saxon fleeces, but we could take only three of the bales for fear of cluttering the Fyrdraca’s benches.

At night we found a cove or river’s mouth, and by day we rowed to sea and looked for prey, and each day we went further westwards until I was sure we were off the coast of Cornwalum, and that was enemy country. It was the old enemy that had confronted our ancestors when they first came across the North Sea to make England. That enemy spoke a strange language, and some Britons lived north of Northumbria and others lived in Wales or in Cornwalum, all places on the wild edges of the isle of Britain where they had been pushed by our coming. They were Christians, indeed Father Beocca had told me they had been Christians before we were and he claimed that no one who was a Christian could be a real enemy of another Christian, but nevertheless the Britons hated us. Sometimes they allied themselves with the Northmen to attack us, and sometimes the Northmen raided them, and sometimes they made war against us on their own, and in the past the men of Cornwalum had made much trouble for Wessex, though Leofric claimed they had been punished so badly that they now pissed themselves whenever they saw a Saxon.

Not that we saw any Britons at first. The places we sheltered were deserted, all except one river mouth where a skin boat pushed off shore and a half naked man paddled out to us and held up some crabs which he wanted to sell to us. We took a basketful of the beasts and paid him two pennies. Next night we grounded Fyrdraca on a rising tide and collected fresh water from a stream, and Leofric and I climbed a hill and stared inland. Smoke rose from distant valleys, but there was no one in sight, not even a shepherd. ‘What are you expecting,’ Leofric asked, ‘enemies?’

‘A monastery,’ I said.

‘A monastery!’ He was amused. ‘You want to pray?’

‘Monasteries have silver,’ I said.

‘Not down here, they don’t. They’re poor as stoats. Besides.’

‘Besides what?’

He jerked his head towards the crew. ‘You’ve got a dozen good Christians aboard. Lot of bad ones too, of course, but at least a dozen good ones. They won’t raid a monastery with you.’ He was right. A few of the men had showed some scruples about piracy, but I assured them that the Danes used trading ships to spy on their enemies. That was true enough, though I doubt either of our victims had been serving the Danes, but both ships had been crewed by foreigners and, like all Saxons, the crew of the Fyrdraca had a healthy dislike of foreigners, though they made an exception for Haesten and the dozen crewmen who were Frisians. The Frisians were natural pirates, bad as the Danes, and these twelve had come to Wessex to get rich from war and so were glad that the Fyrdraca was seeking plunder.

As we went west we began to see coastal settlements, and some were surprisingly large. Cenwulf, who had fought with us at Cynuit and was a good man, told us that the Britons of Cornwalum dug tin out of the ground and sold it to strangers. He knew that because his father had been a trader and had frequently sailed this coast. ‘If they sell tin,’ I said, ‘then they must have money.’

‘And men to guard it,’ Cenwulf said drily.

‘Do they have a king?’

No one knew. It seemed probable, though where the king lived or who he was we could not know, and perhaps, as Haesten suggested, there was more than one king. They did have weapons because, one night, as the Fyrdraca crept into a bay, an arrow flew from a clifftop to be swallowed in the sea beside our oars. We might never have known that arrow had been shot except I happened to be looking up and saw it, fledged with dirty grey feathers, flickering down from the sky to vanish with a plop. One arrow, and no others followed, so perhaps it was a warning, and that night we let the ship lie at its anchor and in the dawn we saw two cows grazing close to a stream and Leofric fetched his axe. ‘The cows are there to kill us,’ Haesten warned us in his new and not very good English.

‘The cows will kill us?’ I asked in amusement.

‘I have seen it before, lord. They put cows to bring us on land, then they attack.’

We granted the cows mercy, hauled the anchor and pulled towards the bay’s mouth and a howl sounded behind us and I saw a crowd of men appear from behind bushes and trees, and I took one of the silver rings from my left arm and gave it to Haesten. It was his first arm ring and, being a Dane, he was inordinately proud of it. He polished it all morning.

The coast became wilder and refuge more difficult to find, but the weather was placid. We captured a small eight-oared ship that was returning to Ireland and relieved it of sixteen pieces of silver, three knives, a heap of tin ingots, a sack of goose feathers and six goatskins. We were hardly becoming rich, though Fyrdraca’s belly was becoming cluttered with pelts, fleeces and ingots of tin. ‘We need to sell it all,’ Leofric said.

But to whom? We knew no one who traded here. What I needed to do, I thought, was land close to one of the larger settlements and steal everything. Burn the houses, kill the men, plunder the headman’s hall and go back to sea, but the Britons kept lookouts on the headlands and they always saw us coming, and whenever we were close to one of their towns we would see armed men waiting. They had learned how to deal with Vikings, which was why, Haesten told me, the Northmen now sailed in fleets of five or six ships.

‘Things will be better,’ I said, ‘when we turn the coast.’ I knew Cornwalum ended somewhere to the west and we could then sail up into the Sæfern Sea where we might find a Danish ship on its voyage from Ireland, but Cornwalum seemed to be without end. Whenever we saw a headland that I thought must mark the end of the land it turned out to be a false hope, for another cliff would lie beyond, and then another, and sometimes the tide flowed so strongly that even when we sailed due west we were driven back east. Being a Viking was more difficult than I thought, and then one day the wind freshened from the west and the waves heaved higher and their tops were torn ragged and rain squalls hissed dark from a low sky and we ran northwards to seek shelter in the lee of a headland. We dropped our anchor there and felt Fyrdraca jerk and tug like a fretful horse at her long rope of twisted hide.