Полная версия

The Imperial Aircraft Flotilla

7 Officer and Williamson ‘Purchasing Power of British Pounds from 1245 to Present’—based on the RPI for 1912 and 2012

8 Singapore Free Press (SFP), 15 November 1912

9 Giving rise to a hoax report in the Madras press that the Indian princes planned to present a number of battleships: news relayed around the world by Reuters before being dismissed as false—SFP, 11 December 1912

10 Straits Echo (mail edition) (SE), 27 December 1912

11 Jagjit Singh Sadhu, ‘British Administration in the Federated Malay States, 1896–1920’ (PhD thesis, University of London: January 1975)

12 HKT, 31 January 1913

13 Lugard, The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa

14 Williams, Running the Show, has a profile: Chapter 11 ‘Sweet talk and secrets—the rise and rise of Frank Athelstane Swettenham’

15 Swettenham, British Malaya, p. 343

16 Swettenham, Footprints in Malaya, p. 67

17 Ibid. p. 97

18 The Times of Malaya and Planters’ and Miners’ Gazette (weekly mail edition) (ToM), 2 June 1916

19 With the exception of the Boer War of 1899–1902, which had proved a very unpleasant shock

20 Wrench, Struggle, Appendices

21 Booth, ‘Lord Selborne and the British Protectorates, 1908–1910’

22 Daily Mail Overseas Edition or Overseas Daily Mail (ODM), 16 January 1915

23 Mackenzie, Propaganda and Empire, p. 148

24 The National Archive (TNA), FO 369/799 ‘Consular Miscellaneous (General)’, Consular Circular No.75275

25 TNA, FO 369/854, ‘Consular Miscellaneous (General) 114–359’

26 Reuters, 25 May 1914

27 TNA, FO 369/854

28 Pall Mall Gazette (PMG), 6 May 1912

29 PMG, 29 January 1914

30 PMG, 11 November 1913; 2 December 1913

31 Overseas, December 1915, p. 18

32 The Aeroplane, 4 August 1915, p. 124

33 Gratton, The Origins of Air War, p. 11

34 Mottram, ‘The Early Days of the RNAS’

35 Baughen, Blueprint for Victory, pp. 51–2

36 Officer and Williamson ‘Purchasing Power’

37 TNA, FO 369/854

38 TNA, CO 616/55, Escott/CO, 13 July 1916; Admiralty/CO, 3 September 1916

39 The Times, Empire Day Supplement, 24 May 1916

40 Overseas, April 1916

41 Flight, 26 October 1916

42 Patriotic League of Britons Overseas, Second Annual Report

43 Wrench, Struggle, Appendices

Chapter 2:

And for the Army, Vickers Gunbus Dominica, and a kite balloon …

Neither Anglo-German naval rivalry in the period before the outbreak of war, nor the Patriotic League’s subsequent efforts at fundraising for a battle cruiser, indicated any lack of interest in aviation on the part of the British public. It was quite the contrary, given the ‘Zeppelin factor’ in popular perceptions of threats to the nation. War in the Air by H. G. Wells was published in 1908; in this the West’s major cities, including London, were destroyed by airships. Press articles in Lord Northcliffe’s newspapers, the Daily Mail and The Times, drew attention to the allegedly paltry resources devoted to aeronautics from 1909 onwards; and in that same year an Aerial League of the British Empire was also formed (and continued with propaganda activities throughout the Great War).1 Then in 1913, the peak year for ‘air agitation’,2 public disquiet over Britain’s new vulnerability from the skies was fanned by reported sightings of German Zeppelins over England (denied by Germany).

For a good eighteen months before the outbreak of the Great War, therefore, pressure had been building for more spending. Great Britain, it was claimed, was lagging behind France and Germany in both government funding and voluntary fund-raising. At a meeting of the Aeronautical Society, then Brigadier General David Henderson stated that the reason the War Office had ordered so few aeroplanes, and none at all between September 1912 and January 1913, was down to lack of money.3 His interest lay in maximising funding for the RFC. Henderson qualified for his pilot’s certificate at the advanced age of forty-nine in 1911, and as Director of Military Training he exercised oversight of pilot instruction from the RFC’s very beginnings. When in August 1913 the War Office created a Directorate of Military Aeronautics, Henderson was put in charge, and retained this responsibility, one way or another,4 until replaced by Sir John Salmond in the autumn of 1917. Henderson was to play the key role on the service side in nurturing the Imperial Aircraft Flotilla campaign during its early stages.

While a Parliamentary Aerial Defence Committee (established in 1909 by Lord Montagu of Beaulieu and others) pressed the Government for greater public spending,5 a number of private money-raising schemes had already been floated. In 1913 Captain Walter Faber MP proposed a voluntary scheme along the lines of the French Avions Départementeaux, which had raised the equivalent of £150,000 and provided the French Army with ninety-four military aircraft and training for seventy-five pilots in preparation for military service.6 On the naval side, a large meeting was called in London under the auspices of the Imperial Maritime League to draw attention to the ‘new peril of the air’. Held at the City’s Baltic Exchange in April 1913, it appealed to Government to take the necessary steps to increase the numbers of both Dreadnoughts and naval aircraft.7 In May, a short-lived National Aeronautical Defence Association launched at a meeting at Mansion House presided over by the Lord Mayor of London, its aim to bring together the various existing pressure groups.8 In Liverpool, three thousand people attended a meeting convened by the Lord Mayor to call for the city’s very own dedicated flying corps to defend it; a message from the Secretary of State for War, Colonel Seely, explained why that was undesirable and invited a contribution of £40,000 from Liverpool to equip an RFC squadron instead.9

The Great War was upon Britain before any of these initiatives bore fruit. However, in August 1914 Britain’s first aeroplane gift of the conflict was indeed forthcoming from a Liverpool businessman under the Imperial Air Fleet scheme (outlined in chapter eighteen). The donor, William E. Cain, requested that it should ultimately go to the Commonwealth of Australia, in recognition of all the support that country was giving to Britain in the war.10 It was handed over in formal ceremony at Farnborough; the Australian High Commissioner’s wife broke a small bottle of champagne on the propeller to christen it Liverpool and Australia thereupon lent it to the British War Office to hold in trust.11 A theoretically Australian-owned Liverpool was then allotted to the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in France at the end of 1914.12 It was a Blériot Experimental 2c model (BE2c), a reconnaissance biplane and the first aircraft to be manufactured in substantial numbers for the RFC.

The second and third aircraft to be presented in the war came from much further afield—or, rather, the funds for them did—from the island of Dominica in the Caribbean. Dominica was an atypical British Caribbean island in many respects. It possessed relatively few landless labourers working on large estates, and had a much smaller planter aristocracy than was commonplace in the West Indies. Green and mountainous, with an area of little more than 300 square miles, most of the population of about 35,000 comprised an independent peasantry speaking a French patois, and owning plots of land of sufficient size to grow their own food and raise small cash crops of cocoa and limes. Dominica had its own resident British Administrator, but was under the supervision and control of the Leeward Islands’ Governor based in Antigua.13

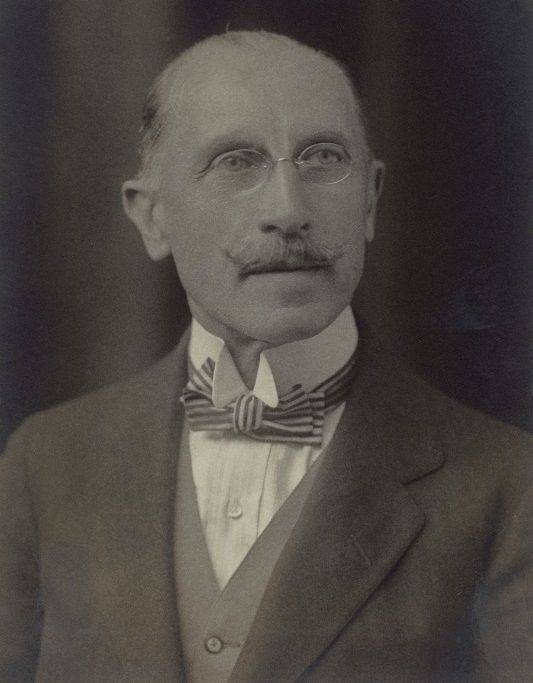

This was Sir Henry Hesketh Bell during 1912–16. Elegant, whimsically humorous, inventive and vain, Bell was nonetheless no mere lightweight. Born in the West Indies of French extraction, Bell had started out as a lowly 3rd class clerk in the office of the Governor of Barbados and the Windward Islands, and worked up from there. As well as winning the backing of one of the foremost British politicians of the age, Joseph Chamberlain, his talents impressed the mandarins of the Colonial Office.14 As Governor of Uganda (1905–1909) he had rolled back a most deadly epidemic of sleeping sickness through the temporary evacuation of designated tsetse fly-infested zones around Lake Victoria, guided by an interest in entomology and his observation that few cases were found more than two miles from open water.15 It was a pioneering and effective measure.

The Governor had a special interest in Dominica, where he had made quite an impact as Administrator from 1899 until his Uganda posting. During his term of office a new road across the island begun by his predecessor (entitled the Imperial Road) had opened up the interior to estate cultivation. He encouraged settlers from Britain to come to Dominica and invest in lime and cocoa estates run along modern lines, on lots carved out from Crown land; he also devised an accompanying scheme to provide insurance cover against hurricane damage to property in the West Indies.16 Again, his scientific curiosity had been in evidence. He made a study of hurricane activity that persuaded Lloyds of London that the venture was worthwhile. Bell was full of ideas, not all of which came to fruition, like his scheme to bring 3,000 Boer War prisoners from South Africa to settle in the interior. (Volcanic eruptions on nearby Martinique warned off the British authorities, which after the scandal of the concentration camps in South Africa probably wanted no more bad publicity over the treatment of Boer captives.)

Sir (Henry) Hesketh Bell by Walter Stonemason, 1919

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Bell had exercised his charm on those in a position to further his plans; wooed the press; sent letters and articles to British newspapers and magazines publicising the attractions of the island; written recruitment pamphlets and a guidebook; and established his own experimental plantation off the Imperial Road (‘Sylvania’), where prospective settlers could see tropical products being scientifically grown.17 All this was in accordance with the imperial policies of Hesketh Bell’s patron, Secretary of State for the Colonies Joseph Chamberlain, who looked to the advancement of the more economically backward corners of the British Empire through the agency of a British planter class, assisted by modern scientific agricultural methods and the provision of improved communications. Chamberlain had viewed Dominica as a test case, and advanced Colonial Office grants for the island’s development.18

Hesketh Bell retained a soft spot for Dominica generally. He wrote of ‘99 per cent’ of its population: ‘These people live simple, quiet lives and are considerably under the good influence of the Roman Catholic Church. In complexion the peasantry and working classes vary from almost pure black to a very light shade of yellow.’19 However, it was the one per cent constituting ‘Society’ that formed his immediate world. During Bell’s period as Administrator, Government House in the island capital, Roseau, had become the heart of social life for its members, whether newcomers or old established families. ‘Society’ comprised the principal officials, planters, professionals, and heads of the main commercial houses. Most were of purely European descent, according to Bell, but the proportion of well-to-do people of light colour and good education was steadily increasing.20 He was a fine dancer, held balls, waltzed with future writer Jean Rhys, then fourteen years old, at a children’s fancy dress dance.21

During his term as Administrator some thirty to forty British settlers and their families were attracted to try their hand at planting on Dominica;22 and the number of Europeans on the island increased from just a handful to almost four hundred between 1891 and 1911. One amongst them was Robin Hughes Chamberlain. Born at Greytown, Natal, in 1887, his father had fought in the British Army in the Zulu Wars, and later settled down as a Justice of the Peace (JP), with as part of his remit to combat gun-running in the vicinity. Initially taught at home by a governess, Robin was dispatched at the age of eight to continue his schooling in England and France. In 1907, he moved to Dominica to learn plantation management at the invitation of a resident, a solicitor to whom he had been introduced in England. After one year he settled down on his own lime and cocoa estate at Wotton Waven outside Roseau.

Already fascinated by aviation (and an avid reader of novels by such writers as Jules Verne and H. G. Wells), it was while on holiday in England at the very beginning of 1914 that Robin Hughes Chamberlain paid his two guineas for his very first short passenger flight, at a flying display at Hendon aerodrome.23 Back once more in Dominica, the Great War broke out. In January 1915 he returned to England bearing letters of introduction from the then Administrator, Edward Drayton, and Leeward Islands Governor Hesketh Bell, with the intention to train as a pilot and serve on the Western Front. Three or four days after his interview at the War Office he was undergoing instruction at Brooklands.

Pilot training in the initial stages of the war usually implied a private income, for potential recruits had to qualify for a Royal Aero Club certificate for which they paid £75 upfront (it was generally refunded later if they were commissioned into the RFC as flying officers). In the British Caribbean islands, as throughout the whole of the empire, British expatriates and residents of British descent and military age made their own way to England after war was declared, usually at their own expense, to join the army as volunteers. Robin Hughes Chamberlain was Dominica’s only pilot.

Dominica had twenty-nine volunteers fighting on the Western Front at the time—most likely all drawn from the ranks of ‘Society’ and especially from the ranks of recent British settlers of military age. One amongst them, who had been studying at McGill University, joined the Canadian Royal Horse Artillery. With the formation of the British West Indies Regiment (BWIR) in October 1915, ordinary Dominicans—labourers, mechanics, and sons of small peasant proprietors—were enabled to volunteer. By mid-1917 there were 139 men from Dominica serving in BWIR ranks. They were employed on the Eastern Front (Egypt, the canal zone, Sinai and the borders of Palestine) on guarding the lines of communication and patrolling railway and pipelines, rather than frontline fighting.24

Dominica’s aeroplane gift came about as follows: On 26 September 1914—when Robin Hughes Chamberlain was once more in Dominica and before he returned to Britain to join up—the island’s Legislative Council introduced a resolution approving a grant of £4,000 from Dominica’s financial surplus, to be offered to the British Government as a contribution to the RFC. Though the relevant official papers of the period do not actually mention the name of Hughes Chamberlain,25 the gift, intended specifically for the RFC, was surely connected in some way with his intention to proceed to England for pilot training, reflecting local pride in one of their number, even if he was a comparative newcomer to the island:

Mr. Rolle and Dr. Nicholls spoke also in support of the Resolution. Both members suggested that the Home Government might be asked to devote, if agreeable, the amount voted to the purchase of an armoured aeroplane to be called ‘DOMINICA’, and His Honour the Administrator promised that in his dispatch he would certainly mention this.26

Thus recorded the island’s principal newspaper.

The Colonial Office subsequently directed that any monetary contribution to the imperial war effort on Dominica’s part should go to the Prince of Wales’ Fund (for the relief of dependents of those fighting at the Front, and others suffering economic effects of the war). But Administrator Drayton argued that he could not, at that late stage, have changed the published proposal, which was warmly supported by public opinion; however he had managed to modify the terms of the resolution so that it no longer specified an armoured aeroplane, but rather that the grant should, if possible, go to the war expenses of the RFC, or be expended on any other war purpose His Majesty’s Government saw fit.

Governor Bell forwarded Drayton’s dispatch to the Colonial Office with his endorsement of the Administrator’s action.27 The island’s correspondent for the London-based West India Committee later reported that despite a cable from the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Dominica’s Legislative Council had persisted in their desire to present the money for some war purpose, preferably to the benefit of the RFC, and Lewis Harcourt had gone along with this.28 Dominica’s Legislative Council (made up of six officials and six nominated ‘unofficial’ local members) passed the modified resolution unanimously on 7 October 1914.

The Admiralty then wrote to the Colonial Office to claim their share for the RNAS:

The £4,000 voted by the Legislative Council of Dominica should be equally divided between the Naval and Military Wings. … It would appear appropriate that the money available—£2,000 in each case—should be allocated for the construction of the aeroplane for the use of the particular Wing. The machine could have a plate fixed to their chassis recording the name of the donors etc., and the donors could be kept informed of any good work done by these machine. … Should the cost of the Naval machine exceed the £2,000, the balance would be borne by Navy Votes, while any small saving would be credited to the Vote for aeroplane construction.29

This letter must have been cleared with the War Office, for the Army Council wrote in identical terms, save that excess costs were to be borne by the Army Vote.30

The War Office later forwarded to the Government of Dominica a photograph of the 100 hp. Gnome Vickers Gun Biplane presented to the RFC with its half share of the £4,000. The photograph was put on exhibit at the Free Library in Roseau in April, and reproduced on postcards placed on general sale for three pence apiece. (An enterprising retailer in Roseau also advertised Dominica Aeroplane Souvenirs in the form of ‘pendants and brooches for the Ladies and Gentlemen and spoons for the table’.)

Picture of Dominica supplied by the Army Council, as reproduced on postcards Courtesy of the West India Committee, London

The promise to keep donors informed of ‘good work’ done by Dominica, and the forwarding of a photograph, set a precedent for future presentation machines from elsewhere. However, the Army Council later specified that the photographs supplied of aeroplanes presented were not for publication.

Unlike the FMS in 1912, there were no local journalistic critics to query the monies voted by the Legislative Council. Then was peacetime, this was wartime. But it was in part due to the nature of the main newspaper in Dominica. Like those of other British dependencies, the Dominica Chronicle carried news of the war issued by the Press Bureau in Britain (some of the larger circulation papers in bigger British colonies also carried Reuters reports). But the Dominica Chronicle was also a Roman Catholic newspaper, with a circulation of about 450 in an overwhelmingly Christian, and largely Catholic, population of only some 35,000. Moreover, Belgian priests had run it ever since the paper’s establishment in 1909 by Bishop Schelfhaut of the Redemptorist Order.31 It had its own special flavour of war reportage, and published the occasional letter from Catholic priests in Europe, including those of chaplains on the Western Front. It can be surmised that their accounts were also read from pulpits to those in the countryside who did not read the Chronicle.

One particularly gripping report was sent right at the start of the war in the form of a letter to the Bishop of Roseau from the Rev. Father Vermeiren in Antwerp. Father Vermeiren, Superior of the Redemptorist Fathers at St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands,32 just over 300 miles from Dominica and part of Schelfhaut’s Diocese, had been visiting his native land of Belgium when the German army invaded. He wrote forcefully from Antwerp in August 1914:

It appears that Germany is also determined to seize Holland, Switzerland and the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. The Franciscan Fathers and the Jesuits have put their fathers, brothers, nay their very houses at the disposal of the Government. I suppose we (Redemptorists) will soon do the same. I will try to make myself useful among the English-speaking soldiers.

His account of the siege of Liège relates an exciting, but entirely false, legend about the renowned French pilot Roland Garros (who was not present, and not killed):

The famous aviator Garros succeeded also in destroying a ‘Zeppelin’ occupied by 26 German officers. All were killed on the spot. Unfortunately, Garros himself underwent the same fate, his aeroplane dropping down like a stone after his glorious feat.33

Yet despite its factual inaccuracies, his letter demonstrates the emotional filter through which war news reached Dominica, and the influence of Belgian Catholic sensibilities. This was not a pacifist Church, and this was holy war.

The RFC’s initial establishment in 1912 was as a unitary body to serve both Army and Navy. But the Senior Service was jealous to exercise complete control over naval air operations, including pilot training and aircraft procurement policy. On the eve of war, in July 1914, the RNAS gained official recognition, so that the RFC entered the Great War as the flying arm of the British Army, and the RNAS that of the Royal Navy. No one was then quite sure what precise role in warfare aviation might come to play, but the expectation was that it would centre on reconnaissance, over land or water respectively (in particular, without the aid of sonar in those days, spotting submarines was easier from the air than from a ship).

When war began, Brigadier General David Henderson decided to lead the RFC, leaving the War Office and taking almost all the aeroplanes the RFC then possessed off to France with him. Henderson’s professional army background had been in field intelligence and reconnaissance, on which he had published two handbooks, and the new BE2c biplane, manufactured from a design developed at the Royal Aircraft Factory, Farnborough, was specifically made for this very purpose, as a stable platform with a good view of the ground. Advanced enough for the blueprints to be the object of pre-war freelance industrial espionage for sale to American firms,34 the BE2c was not equipped with a powerful engine, and was unable to carry heavy machine guns. With the development of air fighting, it was soon realised that purpose-built gun-mounted fighting machines were urgently needed.35 By the beginning of 1915, they had left the design stage and were in British production ready for dispatch to the Western Front; and Henderson himself handed over command of the RFC in France to then Brigadier General Hugh Trenchard in August 1915 to return full-time as Director General of Aeronautics at the War Office.

In those early days, the greater part of the RFC’s aeroplanes in France were reconnaissance craft, and from early 1915 especially the ubiquitous BE2c. After the introduction in mid-1915 of the faster, and more manoeuvrable German Fokker E-type monoplane, equipped with a synchroniser gear that allowed repeated forward machine-gun fire between the blades of the moving propeller, the BE2c proved fatally vulnerable. It also had structural inadequacies. The observer who sat in front of the pilot had a very limited view, and, although he had a gun for defence, could not fire forward at all because of the propeller, while backwards fire was severely hindered by wires, struts, and the tail plane.36 The ‘Fokker Scourge’, as it was known, lasted from July 1915 until early-mid 1916. However, because of production runs, and because inexperienced pilots thrown hastily into battle were often unable to handle faster, more manoeuvrable, but less stable aircraft, the BE2c biplane continued in use in Europe into 1917.37 (It also developed a new role as a night flyer, employed in Home Defence of England against Zeppelin and air raid attack—one for which its stability proved ideal, and where speed and manoeuvrability were unimportant.)38