Полная версия

The Imperial Aircraft Flotilla

ibidem Press, Stuttgart

Table of Contents

Preface and Acknowledgments

Notes

Abbreviations

Part I—How it began

Chapter 1: Introduction—gifts for the Royal Navy, and the Patriotic League

Chapter 2: And for the Army, Vickers Gunbus Dominica, and a kite balloon …

Chapter 3: The Imperial Aircraft Flotilla Takes Off, 1915–1916

Part II—Case Studies: The campaign’s spread and development

Chapter 4: Press and personal networks: Canada and Newfoundland

Chapter 5: Sultan Seyyid Khalifa of Zanzibar and the Royal Naval Air Service

Chapter 6: Tropical Sugarcane Producers: Pacific, Indian Ocean, and Caribbean

Chapter 7: Eastern outposts—bankers and philanthropists of Hong Kong

Chapter 8: The Malaya Air Fleet Fund—the Straits Settlements and Malay states

Chapter 9: West Africa, and most particularly Gold Coast, and Hugh Clifford

Chapter 10: The Rhodesias—friends in high places, a Grey area?

Chapter 11: The Basuto nation, the British sovereign, and 25 Sopwith Camels

Chapter 12: Swaziland, Major Miller, the Union of South Africa, and Jan Smuts

Chapter 13: The Indian Empire: The sub-continent and Burma

Chapter 14: Birds of Ceylon—a very strange campaign indeed

Chapter 15: Furthest ripples of the Great War reach Abyssinia and Siam

Chapter 16: Big and small donors: The Shanghai Race Club and Argentine Britons

Chapter 17: Charles Alma Baker and the Australian Air Squadrons Fund

Part III—How it ended, and epilogue

Chapter 18: New Zealand and Britain’s aeroplane gifts to the Dominions

Chapter 19: Cast list: minorities, colonials, ‘subject peoples’ and native rulers

Chapter 20: The orchestration of support—the British Empire’s last curtain call?

Annexes

Annex I: The Overseas Club

Annex II: The Patriotic League of Britons Overseas

Annex III: The Imperial Air Fleet Committee

Annex IV: Procedural correspondence and instructions

Bibliography I—Primary Sources:

Bibliography II—Secondary Sources:

Copyright

Preface and Acknowledgments

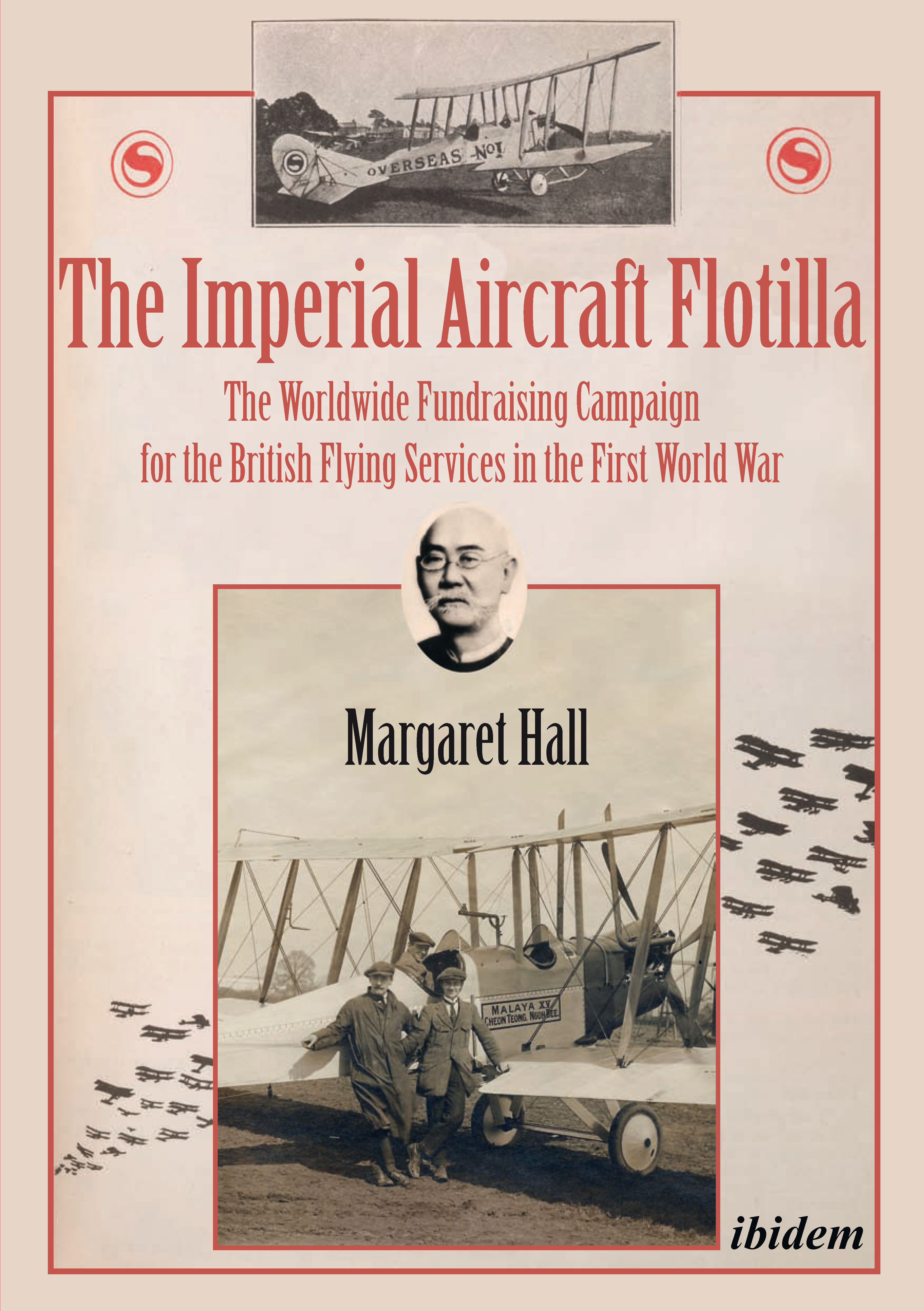

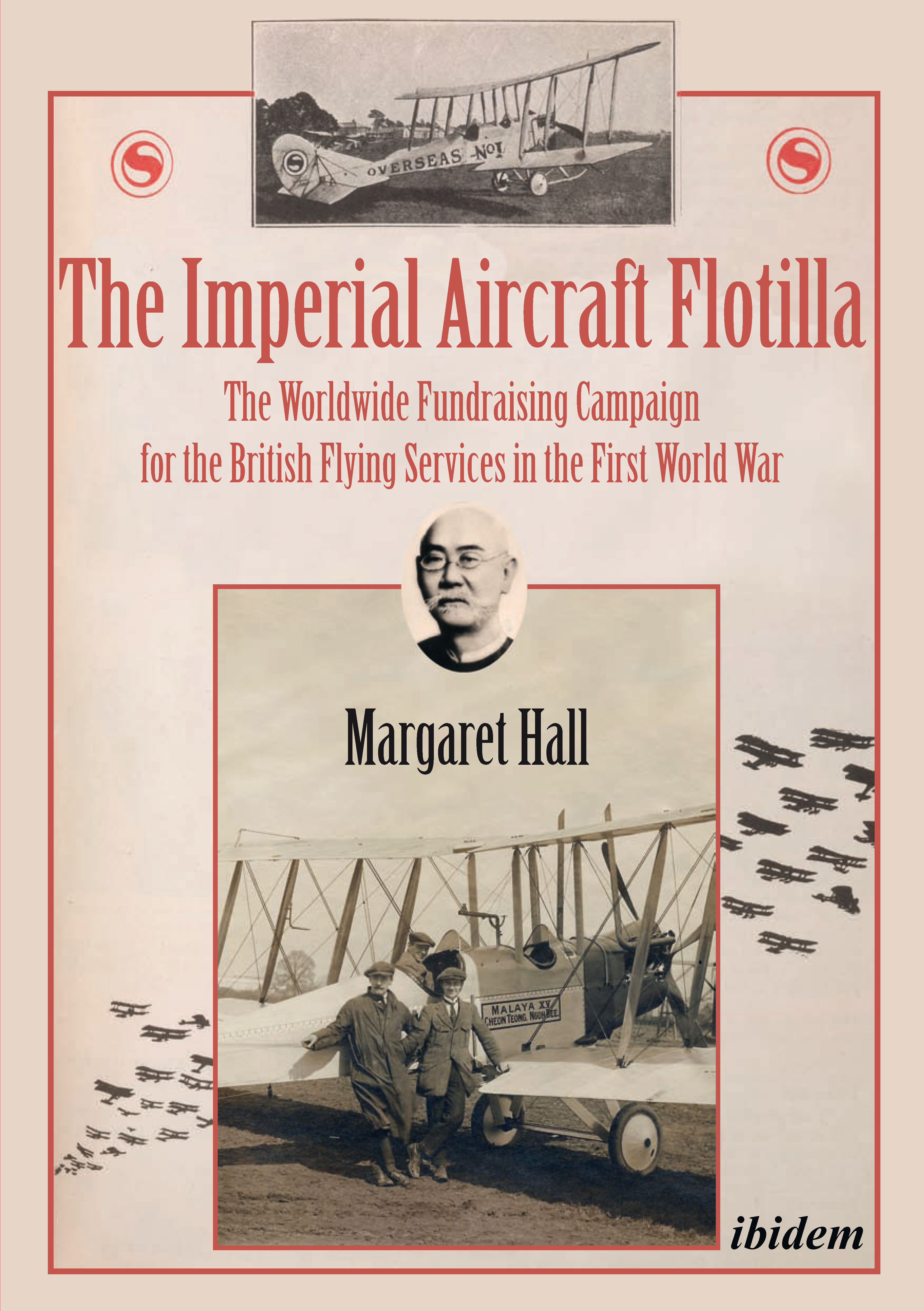

This study arose from a combination of chance, curiosity, and the sudden leisure afforded by retirement. Patrick Khoo unwittingly initiated it in 2008 by asking me to find out why his (Straits Chinese) grandfather had jointly donated a plane to the British flying services in 1916. Previously unaware of the empire’s part in financing Britain’s first air war, initial research discovered a comprehensive survey of 1914–18 presentation aircraft compiled from surviving Royal Flying Corps records.1 Attributions suggested that although colonial governments had gifted some, the overseas public and local rulers had subscribed many more. Curiosity about the underlying reasons for such support led me to widen the scope of my enquiry beyond Malaya and the Straits Settlements, to wherever, and whomsoever, had happened to contribute substantially to the campaign.

Since aircraft were designated after the communities, areas or individuals presenting them, and subscribers put forward their own presentation names, I was drawn by what this might tell us about identities, and how they related to voluntary association with the ‘imperial’ war effort. The First World War, when viewed from a later British perspective, seemed to present a sort of hiatus, or terrible diversion, in the life of the British Empire—some four years of bloody involvement in a catastrophic and all-consuming continental conflict, lodged in between generally successful and profitable British global expansion and the beginnings of that empire’s long decline (just as it attained its greatest geographical extent). I wondered what gaps in the wartime history of the British Empire an account of the overseas fundraising might fill, and why exactly efforts concentrated so much on aircraft?

Because the Imperial Aircraft Flotilla campaign of 1915–18 was above all a voluntary and press driven affair, material for the country case studies largely derived from the British Library’s extensive newspaper holdings, supplemented (or replaced, where there was no local press coverage) by official papers held at the National Archives, Kew. That and other archival material—along with Evelyn Wrench’s published memoirs, also supplied the story from the London end. My primary debt is thus collectively due to the many librarians, research staff and archivists involved, especially those of the old Colindale Newspaper Library, my habitual haunt before its closure; but also those based at the main British Library, Imperial War Museum, and Royal Air Force Museum.

Former colleagues from the Research Department at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (more recently known as Research and Analysis Department) also helped. Sally Healy bravely struggled through inchoate initial versions of early chapters, as well as casting an expert eye over the Abyssinia story; and I am additionally most grateful to David Howlett for the benefit of his helpful comments and suggestions on Empire and Commonwealth, Pacific and Antipodean matters. Any mistakes are, of course, my own.

I thank copyright holders for permission to reproduce images, and would particularly like to express my appreciation to David Payne for allowing me to include the splendid photograph of his grandfather in Malaya XV not only within the book, but also on the cover design. (For the photographic composition of which, my thanks to Su Khoo.) If in any instance I have failed to identify copyright material, despite my best endeavours, I would be glad of information that would allow me to credit ownership. In addition, I gratefully acknowledge the good advice on publishing given by Margaret Ling, and the unobtrusive support of Jakob Horstmann in the completion of the manuscript, and Valerie Lange’s patient efficiency in shepherding me in the publication process.

Shaped by my own past as much as anyone, I offer this monograph to the memory of my father, who worked on aircraft in the Second World War, and that of Dr. T.H.R. (Dick) Cashmore, long-time head of the FCO’s Africa Research Unit and my old mentor on British colonial history and administrative practice.

Margaret Hall

May 2017

1 Raymond Vann and Colin Waugh, ‘Presentation Aircraft 1914-1918’, Cross and Cockade GB Journal, special issue, 14:2 (1983)

Notes

Values: £. s. d. = Pounds, shillings and pence. There were twenty shillings to the pound, and twelve pence in a shilling. A ha’penny = a half penny. A ‘guinea’ was one pound and one shilling (£1 1s 0d) or twenty-one shillings.

Luckily for those of us with little facility for figures, during 1914–18 both the UK and the English-language overseas press habitually expressed subscriptions for aircraft in terms of the sterling production costs for reconnaissance or fighter aeroplanes. These were £1,500 or £2,250 respectively for roughly the first two years of the war, and subsequently £2,500–£2,700 for fighting scouts (equipped with guns but also used for reconnaissance) and fighters, or fighter-bombers. The cost of seaplanes was generally given as £3,500. I have relied on statements of cost and subscription totals expressed in sterling whenever possible.

Civilian Honours: The Order of St. Michael and St. George was designed for service to the crown overseas and was particularly associated with the Colonial Service. In ascending order the ranks are: companion (CMG), knight commander (KCMG), and knight grand cross (GCMG). It ranked in precedence between the two Indian orders—the Order of the Indian Empire (CIE; KCIE; GCIE) and the Star of India (CSI; KCSI; GCSI). The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire was established in 1917 by George V in order to reward civilian service in the war, and consists of member (MBE), officer (OBE), commander (CBE), knight commander (KBE), and knight grand cross (GBE).1 The Royal Victorian Order is in the sovereign’s gift—in descending order, knight grand cross (GCVO), knight (KCVO), commander (CVO), lieutenant (LVO) and member (MVO).

Names: I have used the version most commonly employed at the time by the English-language press and in British official papers, generally indicating variants and alternative spellings, or later changes, the first time that name occurs in the main body of the text. The exceptions to this general rule are those former place-names so well known to an English-speaking readership as to make clarification superfluous (country examples: Abyssinia; Ceylon; Burma; Siam; cities: Peking; Bombay; Calcutta; Madras). Johor in Malaysia was then usually rendered as ‘Johore’ in the press of the day and in Colonial Office papers dealing with the Malay states, and I have kept to this usage, although I well understand that it can invite confusion with that other Johore in India.

1 Kirk-Greene, ‘On Governorship and Governors in British Africa’

Abbreviations

AFC Australian Flying Corps AIF Australian Imperial Force ANC African National Congress ANZAC Australian and New Zealand Army Corps APC African Pioneer Corps ARPS Aborigines’ Rights Protection Society BNC Basutoland National Council BEF British Expeditionary Force BSAC British South Africa Company BSAP British South Africa Police BWIR British West Indies Regiment CEF Canadian Expeditionary Force CMS Church Missionary Society CO Colonial Office DADAE Deputy Assistant Director of Aircraft Equipment DFC Distinguished Flying Cross DSO Distinguished Service Order EEF Egyptian Expeditionary Force FMS Federated Malay States FO Foreign Office FCO Foreign and Commonwealth Office GOC General Officer Commanding IAFC Imperial Air Fleet Committee IWM Imperial War Museum JP Justice of the Peace KAR King’s African Rifles KRRC King’s Royal Rifle Corps LIS Lebombo Intelligence Scouts MC Military Cross MP Member of Parliament NEI Netherlands East Indies NRP Northern Rhodesia Police NSW New South Wales OFS Orange Free State PEMS Paris Evangelical Mission Society PTS Pali Text Society RAF Royal Air Force RAFM Royal Air Force Museum RAS Royal Asiatic Society RCI Royal Colonial Institute RFC Royal Flying Corps RNAS Royal Naval Air Service RNR Rhodesian Native Regiment RNVR Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve ROSL Royal Over-Seas League RPI Retail Price Index SAAF South African Air Force SADF South African Defence Force SANLC South African Native Labour Contingent SANNC South African Native National Congress SCBA Straits Chinese British Association SEF Siamese Expeditionary Force SMC Shanghai Municipal Council STC Straits Trading Company TNA The National Archives US United States VC Victoria Cross WO War Office ZAR Zanzibar African Rifles(See bibliography for newspapers)

Chapter 1:

Introduction—gifts for the Royal Navy,

and the Patriotic League

A great wave of fundraising ‘patriotic’ associations followed in the wake of Britain’s declaration of war on Germany on 4th August 1914, at home but also right across the empire. Quite apart from the Prince of Wales’ Fund (its aim to alleviate economic hardships caused by war) and donations to the Red Cross and to Belgian relief, the public contributed towards funds to provide tobacco for the troops; hospital beds; motor ambulances; aid for the disabled and their dependents; and a myriad of other purposes. Crown Colony legislatures voted money and advanced loans to Great Britain in support of the war effort, according to their means, and more needy areas at least tried to send gifts in kind. In the self-governing Dominions (Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Newfoundland and South Africa) there were scattered initiatives to raise cash locally for war materiel, such as machine-guns to equip the national troop contingents that were formed.

As for subscriptions towards ‘vehicles of war’, the most successful public campaign of all was launched in London at the beginning of 1915. Known as the Imperial Aircraft Flotilla, its inspiration most probably derived from a vote of monies for fighter aircraft by the island of Dominica in the Caribbean (examined in the next chapter). The scheme aimed to attract similar contributions towards aircraft production costs from throughout the British Empire, and was approved by the Army Council in London. Any country, locality, or community that provided sufficient funds for an entire ‘aeroplane’ (as they were usually called at this period) could have it named after them. It was promised that when the machine crashed or was shot down, the name would be transferred to a new one of the same type—initially either reconnaissance or fighter—but quite possibly of later and improved model. In this way the names designated by subscribers and inscribed on ‘their’ aeroplane were to be perpetuated as long as the war itself lasted.

The scheme coincided with rapid developments in military aviation and proved widely popular. Presentation aircraft subscribed from the Dominions, Crown Colonies, and even Protectorates, as well as scattered British subjects resident in allied and neutral countries outside the empire, were randomly dispersed among British flying squadrons from the outset, so that no single ‘imperial’ air formation ever came into material being. But this did not diminish the appeal of the scheme to donors, beguiled by this flotilla of the imagination if not in fact. By war’s end the production costs for more than five hundred and fifty aircraft (aeroplanes and seaplanes) had been gifted in this way from all over the British Empire and even beyond. This is the story of that scheme, how it developed and spread, and its particularities from place to place.

Contributions towards the imperial air war came from far and wide as case studies illustrate, and the motivations of those subscribing were many and various. Apart from British settlers, businessmen and colonial officials, subscribers were often, but not only, drawn from local elites, though they were certainly not exclusively empire loyalists and political conservatives. In places, the fundraising took on aspects of a popular grass-roots movement. It offered an opportunity to support a new arm of warfare that was proving unexpectedly useful in battle, and which right from the beginning of the conflict played a defensive as well as offensive role. For aeroplanes were seen as providing a form of protection against enemy artillery, and thus the campaign appealed to those with kin at the Front, as well as those seeking a vicarious part in the fighting. Of course, they were often one and the same.

The story of the many fundraising efforts in their respective locations throughout the world also casts an incidental light on how the British colonies were run—or ran themselves—at this period of cataclysm which had engulfed Europe, when the imperial shelves were particularly bare. To a large degree, the administration of Britain’s colonial empire marked time from 1914 to 1918, its ranks depleted of colonial cadre of military age who had enlisted in the forces and were fighting at the Front, its local garrisons depleted of regular troops, and often replaced by Volunteers; while in almost, but not quite all British Crown Colonies, public works schemes were held in abeyance until the war was over.

Very many of the British Colonial Governors, and other senior administrators and their wives left at post, had friends and sons and brothers in the war, some of whom were killed or wounded, and they shared the strains and grief of families back home. Some of those officials themselves over military age saw the local fundraising campaign for British aircraft as an indirect opportunity to contribute to the war effort, inasmuch as they were able from afar. At the same time, the name of ‘their’ patch of the empire literally made its mark in a way that was normally acknowledged in British newspapers and by Whitehall.

However, we beg the patience of the readership and start our narrative with an apparent digression, about the pre-war gift of a warship—a Dreadnought—from a Protectorate under British indirect rule. HMS Malaya provided a precedent for gifting vehicles of war from the far corners of empire. It also served as an example that stimulated the launch of a new association in autumn 1914, the Patriotic League of Britons Overseas. The League’s aim was to collect for another warship, but this time from overseas Britons, and when that fund failed, it turned to raising money for seaplanes instead.

For in the naval arms race with Germany that had preceded the First World War, it was not to Protectorates like the Malay states, or even Crown Colonies under direct British rule, but on the contrary to the self-governing white Dominions that Great Britain had looked for practical support and burden sharing, especially Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. These first two countries had sent forces in support of imperial campaigns before—to Sudan in 1884–85, to China (the Boxer Rebellion, 1900) and to South Africa during the Boer War of 1899–1902 in which New Zealanders also took part.

There was no formal constitutional decision-making mechanism in existence to link Britain with the white settler Dominions however, and suggestions of a federal arrangement between them and the Mother Country (such as an overarching parliament, or deliberative joint council) had made no progress. The most that existed were periodic Colonial Conferences after 1887 that provided a flexible forum for the exchange of views, but within the context of ultimate British responsibility for external affairs and defence.

Nor did Great Britain have any desire to be constrained by the interests of the self-governing colonies in matters of imperial defence policy, but there was scope for greater consultation, and clear self-interest on the British part in the practical aspects of cooperation: The new Dreadnoughts—fast, big gun battleships—were very costly to build, initially almost £2 million apiece, and Britain’s concerns increasingly centred on defence of northern waters and containing the ambitious German challenge, as well as on maintaining its dominance of the trade routes of empire. Naturally, however, this was only how matters appeared from a British perspective, as First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill had conceded in a speech presenting the country’s last pre-war Naval Estimates to the House of Commons in March 1914:

Two things have to be considered: First, that our diplomacy depends in great part for its effectiveness upon our naval position … Second, we are not a young people with a blank record and a scant inheritance. We have won for ourselves, in times when other powerful nations were paralysed by barbarism or internal war, an exceptional, disproportionate share of the wealth and traffic of the world.

We have got all we want in territory, but our claim to be left in undisputed enjoyment of vast and splendid possessions, largely acquired by war and largely maintained by force, is one which often seems less reasonable to others than to us … [and] we are witnessing this year increases of expenditure by Continental Powers in armaments beyond all previous experience.1

The King launched the first British Dreadnought in early 1906. By the end of 1912 Britain had built nineteen in all, with another twelve under construction. (The German total was thirteen Dreadnoughts built with another ten under way).2 These capital ships grew ever larger and more expensive, with bigger and more powerful guns. The Naval Estimates rose year by year, so that in the six years culminating in those of 1912–13 Government expenditure, or appropriations for the Royal Navy had attained the dizzying sum of £229 million.3

New Zealand responded to Britain’s appeal for support with an outright gift to the Royal Navy of HMS New Zealand, while Australia became the flag-ship of that nation’s own naval unit, formed for both home and empire engagement. In Canada, however, an imperial naval contribution became a party political issue. At British instigation, Robert Borden, Canadian premier since 1911, proposed that Canada meet the cost of three new Dreadnoughts for the Royal Navy. The proposal divided English- and French-Canadians,4 and his policy, announced to the Canadian parliament in December 1912, met with strong opposition. Nonetheless, in May 1913 his Navy Bill passed its third reading in the Canadian House of Commons. Borden addressed a crowd of more than 10,000 in Toronto—the country’s biggest-ever political demonstration—beneath the motto ‘One flag, one fleet, One Empire’, while a huge model Dreadnought hung in mid-air, flashed electric lights, fired guns, and blew sirens when he rose to speak.5 All to no avail: the Canadian Navy Bill was struck down in the Senate at its first reading.