Полная версия

The Complete Guide to Children's Drawings: Accessing Children‘s Emotional World through their Artwork

When working with these children, it is important to give them the protections they need (for example, by giving them a towel to wipe their hands), but it is also important to invite them to continue exploring the sensory experience, which in many cases can also lead to behavioral change.

Children who show clear preference for gouache could use this experience to learn how to effortlessly take control of the entire page area, but also to maintain its boundaries and improve their gross motor skills.

What to Look for in Children’s Drawings?

For the child, drawing is a daily language and additional medium of communication. The child has never been taught how to draw before, and he advances through the developmental stages freely and intuitively. As in any language, the language of art combines social codes that make it understandable and “spoken”, together with private codes borrowed from the child’s inner world which mark his artwork as unique.

In order to gain a broad perspective on the child’s inner world and self-image based on his drawings, I recommend analyzing at least 25 samples drawn in various techniques (gouache, pastel, markers, pencils, etc.). Analyzing fewer drawings will provide limited indications, representing passing moods rather than broad trends. Accordingly, it is also important to analyze drawings made over a period of at least six months, so as to provide a clear picture of the child’s emotional world and enable comparison to earlier periods.

Interpreting the drawing requires assessing a wide variety of phenomenon, from the way the drawing has been executed and the child’s various artistic choices, through his use of the page area, line pressure and color selection, to analysis of the child’s verbalizations during and after the drawing.

The drawing environment is also significant to the diagnosis: children draw in different styles and with different materials at home and at kindergarten. Drawing at kindergarten next to other children is naturally different than drawing at home, alone or with a parent. Bear in mind that kindergarten drawings are not always spontaneous, and that the teacher often invites the child to the table and focuses him on a particular subject (such as a holiday or a season). In these cases, it is important to compare such artwork to spontaneous drawings made by the child at home.

Free choice is essential to the success of our interpretation. It is important for the child to choose the page size, drawing tools and colors. This will contribute to his free and authentic expression, and paint a more reliable picture of his subjective emotional world.

Having met these conditions, you must check whether the child uses a dominant hand or whether he is still switching hands. You must also check whether he prefers a certain position (lying, standing and even walking). The answers to those questions have direct bearing to the degree of pressure applied to the drawing tool and the angles from which the various elements on the page are drawn.

Finally, you must know the child’s exact age (in months) in order to assess his developmental level. In younger ages, children may achieve developmental leaps every month, so that frequent analysis of their artwork combined with awareness of their precise age will provide clearer indications as to their emotional state.

The drawings shed light not only on the child’s inner world, but also on his social environment and the various influences of the adults in his life – from his parents and wider family, through his teachers to people he met on the street or saw on TV; all of them shape the child’s worldview and all will leave their mark on his art.

How to Respond to Children’s Drawings?

As you pick up your child from kindergarten at the end of the day, you see him bursting enthusiasm as he presents you with his most recent masterpiece. You look at the drawing and don’t know how to react. At first (as well as second) glance, it simply looks like a senseless doodle. And yet, since you want to encourage your child, you mumble things like, “Wow! This is the most beautiful drawing I’ve ever seen!” In most cases, that’s all there is to it: the child seems pleased, and the parent is happy, having succeeded in the positive reinforcement task.

This triple encounter – parent, child and drawing – offers a splendid opportunity to conduct a meaningful conversation about the child’s inner world. But first of all, the parent has to be truly available to attend to the child’s artwork.

As in other parenting situations, this is the first question you need to ask yourselves: “Do I have the energy and patience to totally be with my children?” Granted, it is important to teach our child that we cannot be available to them around the clock; as adults, we have desires, needs and occupations that are independent of his existence. On the other hand, as parents, we are aware of the child’s needs and willing to channel them to other times when we are more available. It is essential to fulfill the promise and “reconvene the meeting” at a later time, instead of just blurting “this is so beautiful”, without even gazing at the drawing.

When you first look at the drawing, it is important that you refer to what you can see – even if it’s just a scribble consisting of seemingly random blots of paint. You can say things like: “I see you drew over the entire page… pressed hard on the marker… used lots of colors/only two colors… drew many lines”. These specific references indicate to the child that the parent is indeed observing his drawing and noticing every little detail he made such an effort to produce.

Naturally, you can also ask the child to explain what he drew, but it’s just as important to respect his answer, rather than badger him with questions such as “Why this way and not otherwise”, or suggest ideas for additional elements. Thus, when your child paints the sky green or red, there is no need to correct him out of fear his perception may be flawed. The drawing is a window onto his inner world, and there is no reason to assume that he is confused about the world outside.

When observing the drawing, bear in mind that it is also a product of his motor development. As such, it is not always pregnant with symbolic meaning. Sometimes your child simply enjoys the process of creating by way of manipulating objects in the world and leaving his mark.

Next, you should wait before complimenting the child, and try to hold a real conversation about the drawing. More often than not, your child will be happy to talk about it. In the conversation, you can mediate between the child’s world and the world of art, and draw his attention to the fact that he loves a particular color that appears time and again both in his drawings and in his room, for example. Invite the child to tell you what he drew, whether verbally or simply by showing your interest through body language and curious eyes.

During the schematic stage (ages 5–8) when human figures tend to appear more frequently in drawings you can broaden the dialogue and talk about the figures’ character. If one character looks angry, for example, you can ask the child why and start a conversation about anger in daily life, about real-life events that may have inspired him to draw that figure, just as you would talk to an artist about his artwork and its emotional underpinnings.

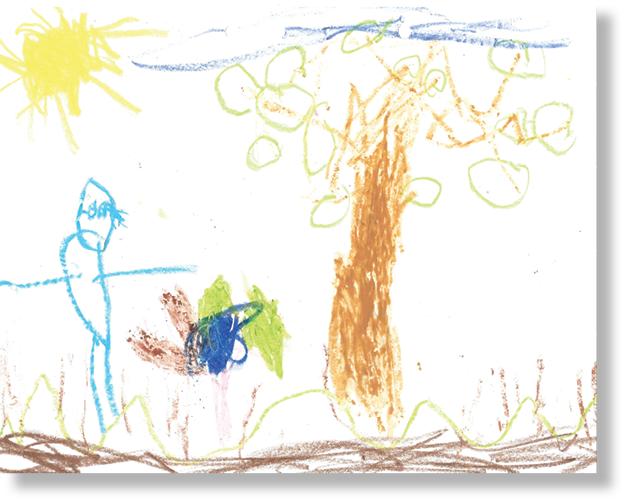

Figure 1-27:Asking questions about the drawing: What grows on the tree? Why is that man sad?

In older ages, you can ask your child about what is hidden in the drawing, and not only about what is clearly visible. For instance, if he drew a house with windows, you can ask him who lives in the room the window’s in. This will start a fascinating and imaginative conversation. You can also use the drawing as a stepping stone to the world of knowledge and riddles: How do clouds form? Why can’t we fly? How do we know the fruits on the tree are ready to eat?

You will not always get answers to your questions – some children will prefer philosophical questions while others will prefer concrete ones, all in accordance with their age and character.

Nevertheless, note that questions such as, why didn’t you draw daddy, or why are you big and mommy small, are unnecessary, and will usually not produce an informative reply. In general, you should avoid overwhelming your child with questions so as not to pressure him.

When you want to give your child a compliment, say things you really mean. Saying things like “this is the most beautiful drawing in the world” is clearly problematic in that sense – it is too demanding. It is better to say, “this is a wonderful gift… this is the most beautiful gift I have ever received”. You can also refer to emotions related to the act of drawing: “I’m so happy that you drew for me… I love it when you give me your drawings… I’ve noticed you enjoy drawing very much…”

When you give a compliment, it is important to encourage the creative process and experience, rather than the final outcome. You can be proud of the drawing and show it to the entire family, but at the same time you must be attentive to your child’s reactions and make sure your pride does not make him feel under pressure to perform. Sometimes the best compliment is to keep the drawing near your bed or in your briefcase.

When lots of drawings fill the house and there is no room for new one, you can ask your child how he would like to distribute them among relatives, as special, personal gifts. Grandpa and grandma will surely be happy to receive a decorated album of drawings. Another option is to put several drawings one next to the other (on the table or on the fridge) and photograph your child as he presents them. You can then place the photos in an album, so that the drawings will not be forgotten.

In different periods of his life, every child needs a different approach to his artwork. Sometimes he likes a kind word or expects a profound conversation, and sometimes he would prefer a dramatic reaction and applause. When there are several children in the house, it is important to attend to each child’s drawings individually, without comparisons. If you use the same compliment with everyone, it is liable to be perceived inauthentic.

Intervention in Children’s Drawings

“Daddy, draw me a castle with knights and fire breathing dragons!” The child asks, and daddy complies. He does his best to draw the most lavish castle, with the mightiest forts and bravest knights, spending time and effort on sketching the wall and windows. Finally, he presents the drawing proudly to his child. The child smiles, hangs it in his room and… stops drawing! From now on, he prefers doing anything but drawing. After a while, whey you ask him in passing why he’s not drawing anymore, he answers with quiet frustration: “Because I can’t draw as nice as you…”

Parents often find themselves sitting next to their child while he’s drawing. The child is completely engrossed with the task: his tongue protrudes, his eyes are open wide and all his muscles are geared to a single objective – his masterpiece. He has been doing it from the moment he learned how to grab the drawing tool, and beyond the sensory experience involved this artwork is a reflection of his rich inner world. Therefore, no intervention in the drawing process can be considered minor; by necessity, it will have a profound impact on inner psychological processes.

There are ways of intervening other than drawing the castle for the child. Some parents start intervening already early in the scribbling stage, in order to help their children advance to the structured scribbling stage, in which the “doodles” become familiar geometric forms such as circle, triangle or square. However, when the children are not mature enough to move on to this stage, they will try imitating forms that are beyond their skill level or worse, give up and stop drawing.

Children will stop drawing for other reasons as well. For example, when they are not only forced to wear an apron but also have to listen to lectures about neatness and orderliness, or when they can only draw during certain hours of the day, the natural process is obstructed and they no longer express themselves freely.

The drawing surface and tools can also deter children. Some dislike drawing on large pages, while others have sensitive skin and avoid rough surfaces. Broken crayons are not necessarily a problem, because often it is easier for children to manipulate the smaller pieces. However, markers that no longer draw or pastel crayons that require strong pressure could tire out children and make them abandon drawing altogether.

It is also important to notice the supply of artistic materials available to the child. If there are plenty of coloring books at home, or if the kindergarten teachers spend considerable time with the children on coloring decorations (for holidays, or whenever the teacher draws a certain shape and invites the children to color it), the child could overemphasize the need to color within the boundaries. He will be busy with the figures and shapes available to him, at the expense of creating original drawings.

The drawing subject may also be significant in cases of refusal to draw. For example, when a child grows in a difficult family reality, he will tend to avoid family drawings or consistently omit one of the family members. In such a case, there is of course no point in asking about the omission.

Another example for intervention has to do with the adults’ attitude to the finished product. For example, when you ask the child, “What is this drawing? Why is the sky all red?”, or when you artificially identify familiar objects in what is clearly an unrecognizable scribble (“this looks like a flower, and this looks like a heart). Such an attitude communicates to the child that he has to draw recognizable elements that mimic reality. Next time he draws, he might “force” the drawing to be more realistic, and when asked about it, he will try to explain what he drew in a way that would please the adults around him.

Finally, when you talk with the kindergarten teacher you have to remember that the child is also listening. Saying things like, “She’s already four years old and still doesn’t draw houses!”, can make the child feel frustrated and stop drawing altogether.

Why, then, do adults intervene?

Some adults intervene because they fear their child is not drawing at an age-appropriate level, because of some developmental problem. By intervening, they “teach” the child to mimic age-appropriate patterns and abilities. Note, however, that just like copying from other children, it is easy to identify children who “fake” when they draw, using similar indicators used to identify fake handwritings. Namely, when children use elements that are out of sync with their inner development, their drawings will have a hesitant and inconsistent quality. Thus, studying an adult design and mimicking it could help the child produce a drawing that may look impressive, but a professional observer will easily identify it as fake.

Figure 1-28:Intervention drawing, with adult contours

Others intervene when they want to correct mistakes, to teach the child to draw “correctly”. In art, however, there is no such thing as “correct” or “incorrect”. The drawing is designed to mirror the child’s inner world and as such there are no correct or incorrect ways to go about it. Moreover, children who paint red skies are usually perfectly aware of their real color, but choose to draw them red for other reasons.

This attempt to “teach” the child how to draw correctly will fail in most cases. An interesting study (Cox 1996) on children at the “tadpole” stage (age 3) found that they become attached to their tadpole figure and are slow to abandon it even after observing college students drawing conventional human figures. In fact, the reason for the intervention – be it fear of developmental lag or any other reason – does not matter. The drawing mirrors the child’s inner world and “fixing” it will change nothing. Worse, as you have seen, it could disrupt the natural process. Note that when discussing adult interventions I do not refer to therapeutic interventions, as in occupational or art therapy.

When the girl who made the following drawing was 5½ years old, her mother contacted me in order to understand why she omitted the arms in her human figure drawings. At first, she told me that she had tried to intervene and check whether she was aware of all the body parts the arm is composed of (such as forearm, palm and fingers). When the child demonstrated her awareness, the mother continued to explain how important it was to actually draw all these body parts. Her daughter agreed with her, and yet, after several days, she returned to draw armless figures.

Figure 1-29:Armless human figure

My analysis of her drawings, including figure 1-29, indicated that she was a creative girl with a strong desire to control her environment. She made an effort to seem perfect on the outside, and her coloring was particularly meticulous. Despite her relatively developed emotional side, she preferred to set clear boundaries for herself when it came to sharing.

Nonetheless, she continued to draw armless figures because this is an age-appropriate phenomenon! Many children at her age draw complete figures and even dedicate considerable attention to drawing the fingers, and yet many others ignore the arms completely. This is highly typical of children aged 5–7 and there is no point persuading them to draw otherwise, mainly because they will do so in due time.

Naturally, most adult interventions are motivated by good intentions, without awareness of any negative effect they may have, such as refusal to draw. Many adults treat painting just like any other motor skill acquired with adult guidance, such as cooking, and are simply unaware of how important it is for the drawing child to experience and explore on his own.

Still, what can you do when the child refuses to draw?

First, you must make sure the reason for his refusal is not any physiological disorder (motor problem, visual disability, low muscle tone, learning disability, etc.). Once this possibility has been rejected, there are several courses of action available to you. If your child feels his drawings are not “good enough” because they are graphically inaccurate, take him to the museum and show him the wide range of “inaccurate” artworks. If your child asks you to draw for him, use your non-dominant hand to make a “bad” drawing on purpose. Another possibility is for you to draw with your eyes shut and ask your child to guide your hand.

Next, you can ask your child to turn your scribble into a recognizable drawing and then switch parts (Winnicott 1971). Finally, you can designate a special drawing notebook. This way, your child will have a sense of continuity from one drawing to the next and will be able to show his drawings around. In addition, the notebook will encourage him to make up a serial story around the drawings.

If you’ve tried several approaches and your child still refuses to draw, and assuming the possibility of physiological issues has been rejected, you should remember that drawing is a hobby and that there are plenty of other creative avenues still open to your child.

Boys versus Girls

Society tends to treat boys and girls differently. One study (Huston 1983), for example, explored adult attitudes towards infants at the age when their sex is hard to distinguish. It was found that when the infant wore blue cloths, adults used to hold it high and throw it in the air. When it wore pink, however, they treated it gently, held it close to their chest and avoided rough play.

This is just one of many examples proving the social influence that molds boys and girls into gendered roles. On the other hand, many believe that gender identity is primarily innate. For instance, little boys independently choose “boyish” games (cars, superheroes), even when they have “girlish” toys (dolls, kitchen) at easy reach, and vice versa (Hoffman, 1964).

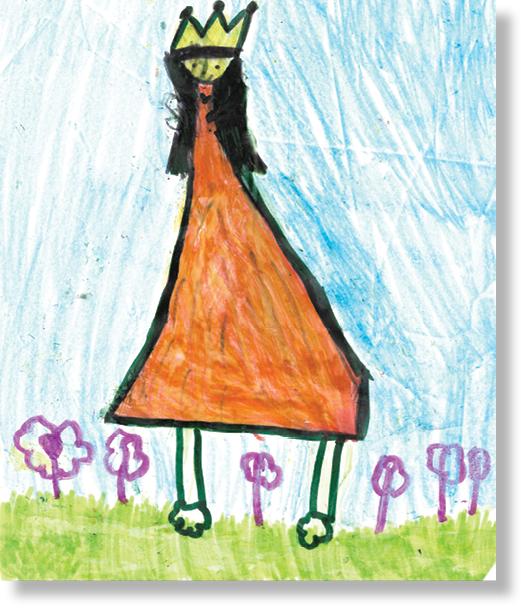

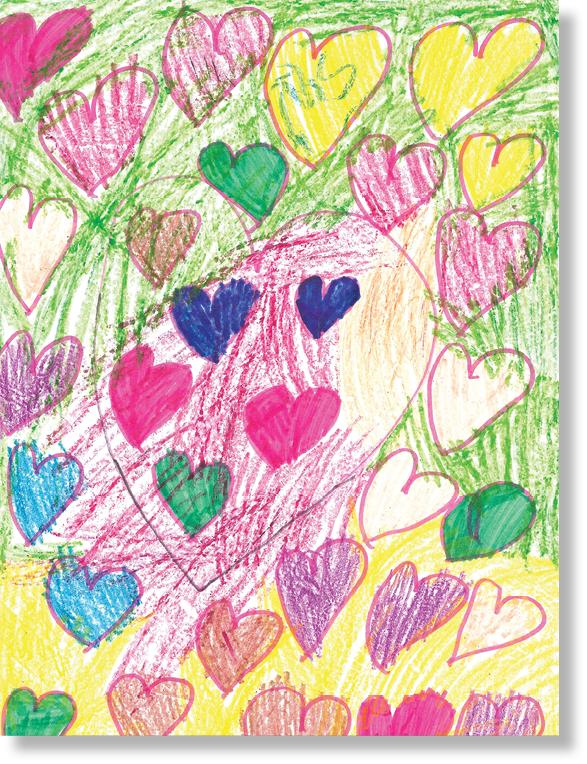

Figure 1-30:Typical painting by a girl

Just like playing with dolls, drawing also gives children the opportunity to create an imaginary world and draw themselves as superheroes or delicate princesses. Everything is possible on the drawing page and children relish this absolute freedom. Beyond themes that are popular among all children regardless of gender, such as family or holiday drawings, most boys tend to draw superheroes combined with various angular shapes, while girls prefer princesses combined with hearts, flowers, jewelry and similar details.

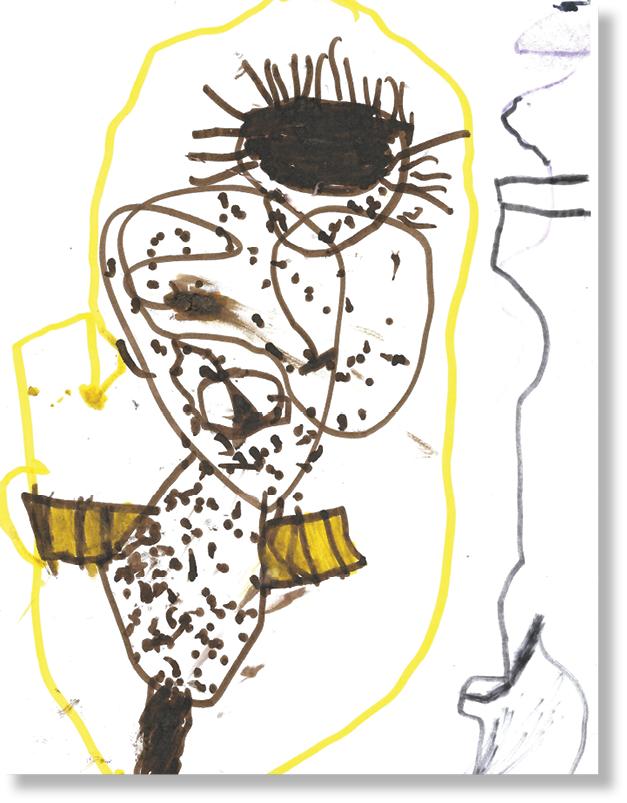

Figure 1-31:Monster drawing as a normative tendency

Unless there are indications to the contrary, drawings of monsters and violent heroes are considered normative among boys, and are usually not considered as evidence of any internal distress or anxiety experienced by the child. Sometimes they lead to precisely the opposite conclusion: the child who draws monsters is socially integrated and understands the social codes of the community, and accordingly has interests that are shared with his peers.

The drawing subject can thus be misleading and even cause unnecessary concern among adults. It is therefore important to get to know the children’s world and understand their language.

In order to identify signs of distress, it is more important to attend less to the subject per se and more to graphic indicators in the drawing, such as the degree of pressure applied on the drawing tool, line quality and color combinations.

A classic social learning study (Bandura 1971) showed that girls usually allow themselves to express negative emotions only when certain this is socially acceptable. Also when drawing, girls tend to attach greater importance to the final product and the way it is received. If the girl is preoccupied with her looks in real life, the figures in her drawing will be rendered accordingly: each figure will have jewelry, hair accessories, makeup and well-drawn eyebrows and lashes. To arrive at such carefully detailed results, they tend to plan their drawings more carefully than boys, color them gently and execute the entire composition with great accuracy. They also tend to draw “acceptable” subjects and avoid subjects that are controversial in terms of gender identity.

Importantly, girls in therapy will use drawings as a therapeutic tool to externalize anger and frustrations, but will tend to do it in a supportive environment. In such an environment, they are less preoccupied with how the final product looks.

Another classic study explored gender differences in graphic expression (Hesse 1978). This study found that significantly, boys’ line style and shape design tends to be characterized by dynamism and momentum, while girls prefer clearly defined lines combined with structured static forms. Girls’ subjects are clearer and more understandable, and they are careful to plan their composition and draw a baseline (the ground line), while boys the same age drew a baseline in only half the cases. In terms of coloring, girls tend to use a greater variety, while boys clearly prefer using 1–3 colors out of the entire pack.

Another significant different between the sexes has to do with brain structure (Restak 1982). Girls’ fine motor skills area is larger and better developed than boys’ and this is perhaps why their drawings are considered “nicer”, as well as their handwriting later on. They tend to draw small and carefully rendered figures. This does not mean that boys develop more slowly, but simply that the developmental trajectory used to judge their drawings is different than that of girls. Another difference that may have to do with brain structure is that girls seem to be better in reading facial expressions. This contributes to their developing social skills and also explains their preference to draw human figures and depict the relationships between them.