Полная версия

The Complete Guide to Children's Drawings: Accessing Children‘s Emotional World through their Artwork

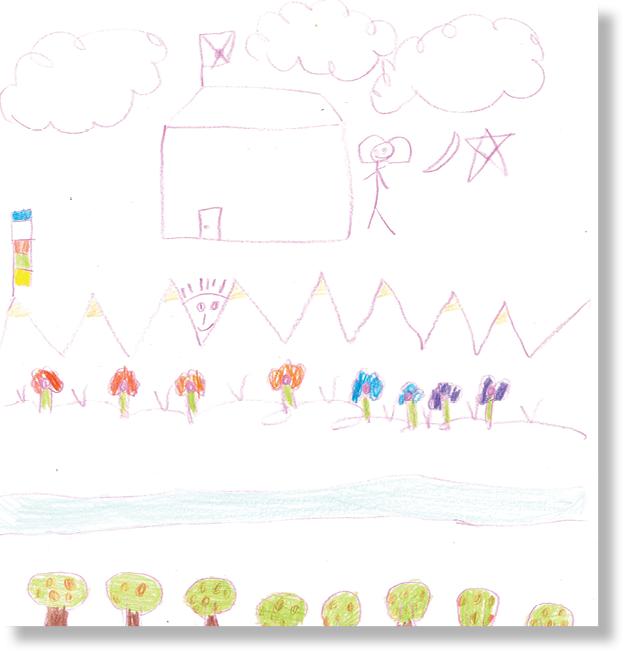

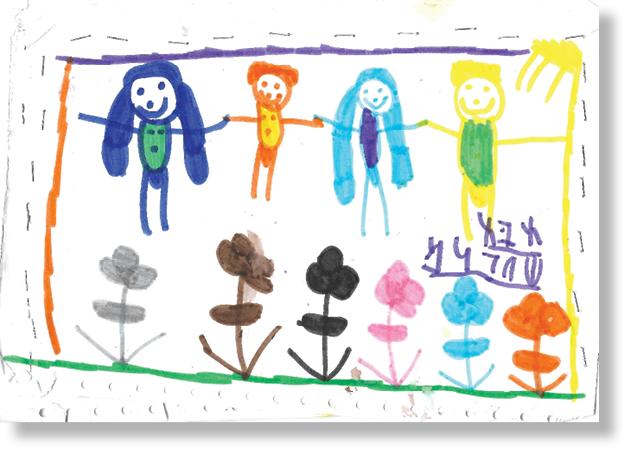

Figure 1-13:Drawing by a Tibetan child with multiple land lines

Multiple land lines are a fascinating phenomenon in drawings by Tibetan children. Despite being in the midst of the schematic stage, well aware of the locations and colors of earth and sky, these children choose to revert to drawing row after row over imaginary land lines.

This style may be affected by the Tibetan prayer wheels, set in a row one next to the other, which represent balance and recurrence which are part of their religious worldview.

At this stage, children still find it difficult to draw figures in profile or in motion, because doing so requires them to ignore schematic characteristics and omit some of the organs (such as a hidden eye, or an arm that is only partly visible while the figure is walking). Instead, they draw “everything that has to be there” by making some organs transparent. Use of colors is also schematic, as children tend to use basic colors rather than shades and combinations. Finally, schematic children attach central importance to the drawing’s subject, and can even engage in a deep conversation about its meanings and the story hidden in the drawing.

Stage 5: Pre-Realistic Stage – Ages 8–11

Pre-realistic children acquire motor skills which enable them to refine their depiction of reality and differentiate objects more accurately. Thus, we see attention to various types of cars or trees, local animals, etc.

Figure 1-14:Yaks in a typical Tibetan pre-realistic drawing

By this stage, each human figure receives individual attention, with its own typical details and accessories: glasses, buttons, bag, hat, and so on.

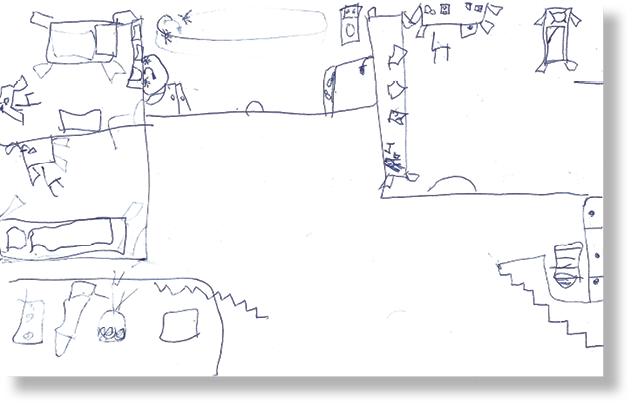

In each human figure drawing, the pre-realistic child tries to resolve graphic difficulties such as: How to draw a person lying down? Should I draw all the table legs or only those visible from this angle? How to draw the house interior and exterior at the same time? In most cases, the difficulty is resolved by flattening the image: for example, houses will be drawn as seen in figure 1-15.

Figure 1-15:Typical flattened house drawing

As abstract cognition develops, this flattening tendency will disappear.

Since the pre-realistic child wishes above all to document reality, he is careful to maintain the proportions among the various objects in the drawing.

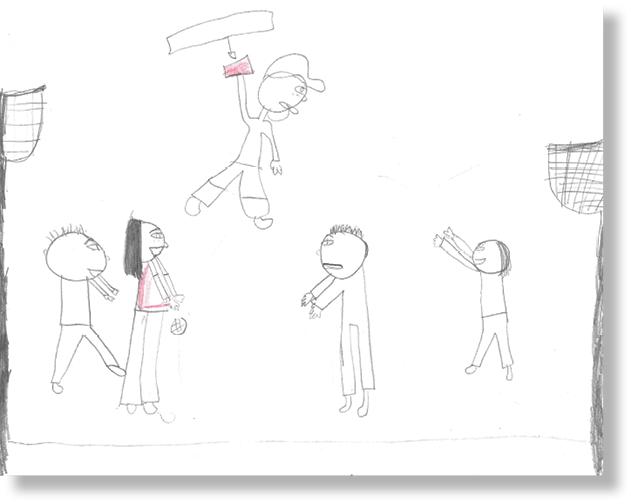

His subjects combine figures from his intimate world (family drawings) with imaginary and historical drawings (Bible stories), as well as current affairs (war scenes, etc.).

In terms of psychological development, Piaget calls this period the operational stage, in which the child can grasp concepts of preservation (of quantity and weight) and to organize items in groups according to common denominators. Problem solving no longer relies exclusively on trial and error, but also on social rules of conduct, as well as the opinions and emotions of others. The child’s understanding of reversibility (every change in location, form, or order may be reversed) and of hierarchic relations refines his family drawings, to which other groups are added, such as sports teams. Moreover, the child begins to attach several drawings together to represent a continuous plot.

Figure 1-16:Family drawings advance to group drawings

The pre-realistic drawing represents an overall improvement in quality: the child refines his composition and landscaping skills. He draws the same subject repeatedly with improving skills, particularly in terms of his ability to render graphic elements that are unique to specific human figures.

At this stage, children begin to view their drawings as an expression of their self-efficacy. This is why they tend to compare their drawing abilities at these ages.

Stage 6: Realistic Stage – Ages 11–14

At the realistic stage, the child/adolescent is fully aware of his environment and has advanced graphic abilities that enable him to start dealing with depictive difficulties by refining his technical skills, such as games of light and shadow, three dimensions, complex scenarios, shades of color, perspectives, etc.

Figure 1-17:Combined techniques indicating improved spatial perception

The subjects become more realistic and less fantastic. The realistic pre-adolescent attaches greater importance to proportions among the various elements, to the point of depicting different shades of color to emphasize their relative locations.

As opposed to drawings made in earlier ages, by this point the child will deemphasize his own image and assume the reference point of an observer.

According to Erikson, the most significant social group at this age is the peer group, which also explains why (unless otherwise directed) realistic children will tend to draw peer groups rather than families.

Figure 1-18:Advanced drawing of facial organs

The drawings typically depict complex situations, including copies of diagrams, illustrations and cartoon figures. We see more faces in profile and detached organs (eyes, mouths). The interest in the human body which is typical of these ages will also be seen in the drawings, with methodical attempts to produce accurate anatomic sketches.

Nevertheless, the young realistic artist is often dissatisfied with the final result, seen as a distorted, inaccurate rendering of the landscape, building or human figures. Since there is no clear educational requirement to continue drawing on a daily basis (unlike other skills, such as writing), many children stop drawing at this age and remain at this level as adults, with bad memories from their difficult and exhausting drawing lessons at school.

The Scribbling Stage – More than Meets the Eye

Simple comparison of scribbles made by several children from the same kindergarten will show that they do have some distinct characteristics: some children prefer certain colors and refuse to use all crayons. Some children apply strong pressure, while others do not. Some scribbles are composed mainly of round and spiral movements spread over the entire page area, while others are dominated by broken lines in a limited area.

In order to properly interpret a scribble and explore how the child translates from the sensory modality to the drawing modality, you must gather a considerable amount of information about the child’s graphic language. Most studies on emotional interpretation of children’s drawings begin from that starting point. When we study graphic language we focus on the quality of the pressure produced by the child on the drawing tool and the way the child conducts it on the surface. For example, weak pressure that is not the result of physiological problem may indicate certain inhibitions. Other indicators include the style of the lines (fragile, disjointed, thin or wavy lines, etc.) and the way they cross each other; the general planning of the page; the child’s ability to compose and combine various geometric forms; how he colors and fills in the forms; his attention to detail, etc. The key point of graphic expression is that the pattern of the drawing on the page is affected by the muscular pressure applied to the drawing tool, which is in turn affected by cerebral activity and the child’s inner emotional world.

Scribbling is the first step in the graphic expression process, and in that it is akin to the babbling which precedes speech among infants. Although scribbling is a preliminary experience, children who scribble soon begin to develop personal preferences and show a clear desire to produce diverse and interesting artwork. Some children start scribbling already at age one, and soon proceed to draw familiar geometric forms, followed by realistic objects (house, tree, etc.). At school age you will still find evidence of scribbling, for example beside the written lines in the notebook. Writing letters, of course, requires prior knowledge in scribbling and drawing.

During this stage, the child begins to develop his spatial orientation and ability to experience the world kinesthetically as well as through the senses. The scribbling process also provides sensory stimulation, and children at this tender age often taste their crayons. At this stage, children understand the world actively and creatively, so that they affect the information rather than receive it passively. In my opinion, older children will also do well to understand the world in this active approach. During this period, it is important to allow the child to experience a broad range of nontoxic materials such as gouache, markers, finger paints, and pastel crayons, as well as a broad range of surfaces such as rough paper, papers of various sizes and colors, wooden boards, Bristol papers and newspapers.

Some children actively seek these surfaces, ignoring the fact that the surfaces may already be written over. It is also important for children to experience a wide variety of kneading materials: dough and other foodstuffs, modeling clay, etc. to stimulate their senses.

At this stage, the edges of the surface are not absolute boundaries for the child, who tends to “stray” to nearby surfaces. When the child first starts to draw, he does it accidentally and admires the product. His fascination and that of others around him challenge him to continue exploring this dimension. However, only when you begin identifying recurring trends in the drawing will you be able to start talking about deliberate drawing that represents conscious intervention by the child.

Drawing is fundamentally a muscular activity and as such, it attests to the child’s temperament and adjustment to his environment.

When the child draws, he is required to balance between movements away from the body (executed by relieving pressure, as you can see in Figure 23) and movements towards the body (executed by contraction and applying pressure, as you can see in Figure 22). Internalizing this pressure is evidence to the maturation of certain brain and nervous system mechanisms and helps the child refine his equilibrium system. By way of drawing, the child enhances his control over various bodily organs and adjusts his bodily posture to the type of drawing he wishes to produce.

Figure 1-19:Example of a scribble from the circular sub-stage

A student of creative education, Victor Lowenfeld (1947) saw drawings as reflecting the child’s view of reality. His studies led to the identification of fours scribbling sub-stages: (1) Disordered or lacking control over motor activity; (2) Longitudinal or controlled repetitions of motions; (3) Circular – further exploring of control motions demonstrating the ability to produce more complex forms; and (4) Naming, where the child tells stories about the scribble, gives it a title and demonstrates symbolic condition.

In other words, according to Lowenfeld the child acquires skills as he practices drawing, wherein lies the importance of recurring drawing elements. Recurrence is also stressed by Rhoda Kellogg (1969), who compiled a list of 20 basic scribbles that represent the foundations of graphic development. Kellogg proceeded to identify 17 compositions which suggest certain regularity in the scribble’s location on the page.

Kellogg argued that scribbling has nothing to do with the child’s present psychological development, but that it is evidence of collective hereditary memory.

Namely, the various scribbling variations are not acquired from the environment but inherent to the human organism from birth, indicating the drawer’s uniform sequence of graphic development and nothing more.

Kellogg’s studies are considered controversial. Many of her critics argued that the basic patterns she identified appear in only some of the scribbles in her record, so that they cannot be considered indicative of a universal graphic development sequence.

Likewise, while Kellogg argued that the motive for scribbling is an innate urge to build and to create, that has more to do with the collective unconscious than with the desire to depict external objects, her critics (e.g. Matthews 1988) presented a large number of drawings by children who accompanied their artwork by statements of their desire to document reality, notwithstanding the jumble of lines on the page. Personally, I believe children are affected by a primary urge to create while at the same time being affected by the need to communicate with the environment by way of borrowing existing concepts (archetypes such as the recurring house pattern).

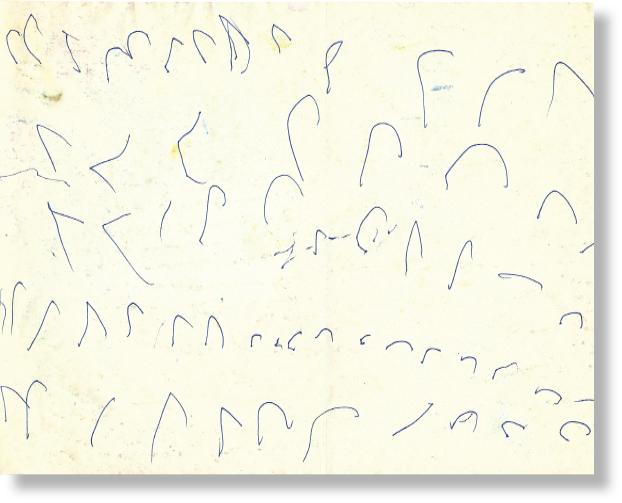

Figure 1-21:Letter-like symbols

The scribbling stage is also when mandalas begin to appear in children’s drawings. These are rounded forms, from which lines extend in various directions, or forms crossed by lines). By drawing mandalas, children acquire the ability to later draw suns with rays, or tadpole figures (human figures without torsos).

Between the ages of 1½ and 3½ you can also find scribbles reminiscent of letters, which are called «letter-like symbols».Such shapes cannot be found in all drawings, but when they are found they do seem to resemble handwriting, including careful attention to lines and spaces.

Such writing attests to the development of fine motor skills, as well as to enhanced brain-eye-hand coordination and spatial orientation. It does not, however, suggest the child is ready to learn how to read and write. Rather this is a passing fad which will return, in some children, around age 4. At this age, many children start writing their names and often use mirror writing, suggestive of internal development processes related to hemispheric dominance.

In art therapy, scribbling is considered a nonthreatening and even soothing technique in that it is completely purposeless. Scribbling is not oriented towards a final outcome and not committed to produce a pretty and accurate picture, but promotes an experiential process free of any rules or inhibitions (Kramer 1975).

Another phenomenon typical of this stage is drawing on walls. Almost every parent is familiar with this situation, facing the masterpiece and asking himself, why on the wall of all places?

The very act of drawing provides sensory stimulation and enjoyment, and since children at the scribbling stage have only begun internalizing the idea of boundaries, they see absolutely nothing wrong with testing their skills and expressing their talents on surfaces deemed unconventional by adults, like walls.

Drawing on walls is just part of a long sequence of attempts by children to test their abilities. The desire to move objects and “produce artistic output” is expressed in their playing at the sandbox, in the bathtub or on the dinner table – when the child grabs a fruit and realizes he is capable of taking it to his mouth. Children also leave their mark artistically, as if marking a territory, as if saying, “Look at me! Only I could draw that!”

The child experiences and explores the world in his own way, still without understanding why drawing is allowed on one surface but not on another. Since the sensory experience of drawing on a wall is completely identical to that which accompanies drawing on paper, children stop drawing on walls only after internalizing the spatial and conventional boundaries and enhance their ability to communicate with the adult world. In the meantime, frustrated parents can designate a wall space for scribbles, frame existing scribbles or let their children paint on china with water-based markers. Remember, however, that any such solution is liable to fail as long as your child has not internalized the concept of boundaries.

The parents of the 2 years and 9 months-old girl who made the following two drawings told me that recently, her behavior changed. Since they had been collecting drawings for a year, I could compare them and identify the differences. In her scribbles, I could see evidence of her willfulness and resistance. She wants to do everything herself and relishes in dictating her rules to the environment.

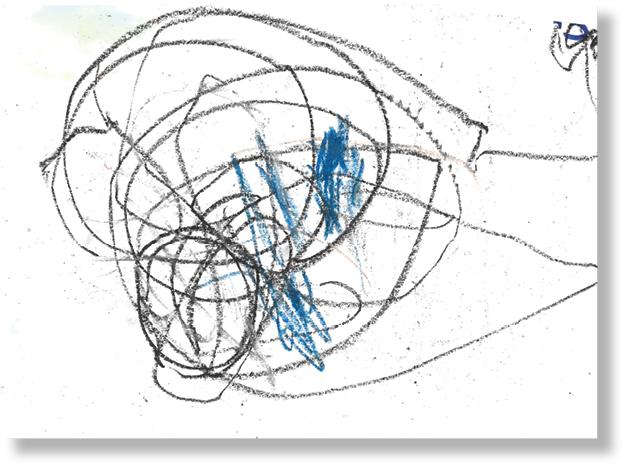

Figure 1-22:Shrunk and highly pressurized scribble

Among other things, this is evident in the strong pressure she applies to the drawing surface. In her scribbles, you could clearly see when everything began to shrink and she showed a withdrawal tendency that concerned her parents tremendously.

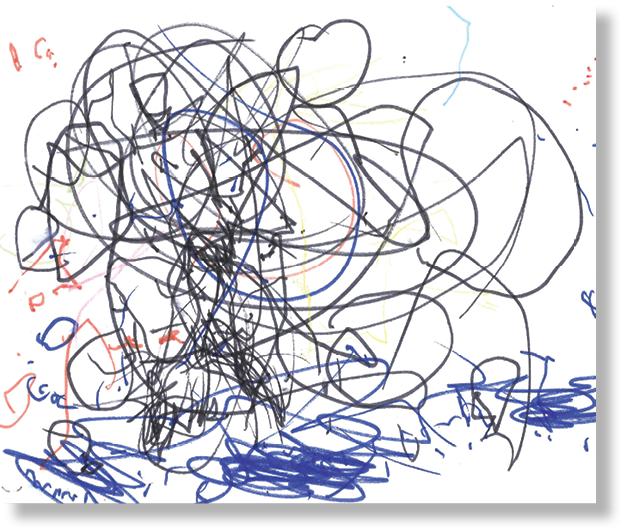

Figure 1-23:Unconstrained scribbling with balanced pressure

Her more recent drawings indicated that she was more attentive to external demands than to her own desires and acted quickly to please the environment. I could also see signs of the extraordinary fears which caused sleeping disorders, constipation and irregular eating patterns. Socially, she began to evidence adjustment difficulties and at home she kept clinging to her parents. After the parents were advised to move her to a kindergarten with fewer children, her scribbles showed a change for the better.

To conclude, the graphic complexity of every scribble (which makes it appear senseless) requires thorough scrutiny of a large number of drawings before any comparisons can be made. Such comparisons can offer important insights into the child’s temperament, behavior patterns, difficulties and fears he may be experiencing.

The Emotional Significance of Drawing: Process and Drawing Tool

The artistic experience is basically a sensory experience combining multiple modalities. Through this experience, the child structures his worldview. For the child, drawing is friendlier and more comprehensive than verbal expression; through drawing the child can create something out of nothing. This is in fact the starting point of the creative experience in art therapy: through creative experience, the child undergoes a process of trial and error which enables him to discover and express his inner world. Children “use” drawings as a way of sublimating aggressive drives and relieving stress. They let their imagination run wild and draw the world as they see it, rather than as an accurate copy of reality.

Sitting Position

At first, you must pay attention to the child’s sitting position: it is important for the child to feel comfortable, with the table and chair adjusted to his size. Don’t be upset if you see your child drawing lying down, because this position enables him to place more of their body’s surface on the floor, and often helps them concentrate on their drawing. Some children will prefer this position also in older ages and you will find them doing their homework on the floor, but in most cases this is a fleeting phenomenon.

For some children, lying down is preferred because their shoulder muscles are too weak for them to draw while sitting or because they have difficulty focusing their eyes and thus want to draw as close as possible to the page.

Page Size

The size of the page is also significant for the child. Above all, it should fit his physical size and experience in drawing. At the scribbling stage, it is recommended to use large pages. At this stage, the child is unaware of the page’s boundaries and it is important for him to delve into the experience of drawing. When the child begins to develop his drawing skill, he can use smaller pages and even let him try small notes that will encourage him to concentrate and develop fine motor skills.

Naturally, there is no mandatory age-to-page-size ratio, and it is always recommended to combine various page sizes so as to allow the child to hone his skills in drawing small details as well as to draw in a more uninhibited way. However, you should observe the degree of confidence and satisfaction experienced by the child: when an unconfident child is asked to draw on a large page, he might give up before even starting. Thus, make sure the child is exposed gradually to various stimulations and let him pick the page size that is best for him.

Drawing Tool

Drawing tools also play an important role in the process, and each exposes the child to a different experience. First, the way the drawing tool is held can indicated disabilities that could become manifested in a later age. For instance, children with low muscle tone will grasp the tool tightly within a fisted hand. Note, however, that you must be wary of rushing into conclusions, because children undergo multiple change processes at this age. In any case, if drawing requires the child to apply too much force, which wears him down and prevents him from drawing as much as he would have liked to, you are advised to seek professional diagnosis.

Markers are quite mechanic in nature, particularly the thinner markers that emit a screeching sound when applied to the paper. Usually, children aged 4–5 prefer markers, as you can see in figure 1-24. It is important for them to be precise when coloring the house drapes or the monster’s eyes.

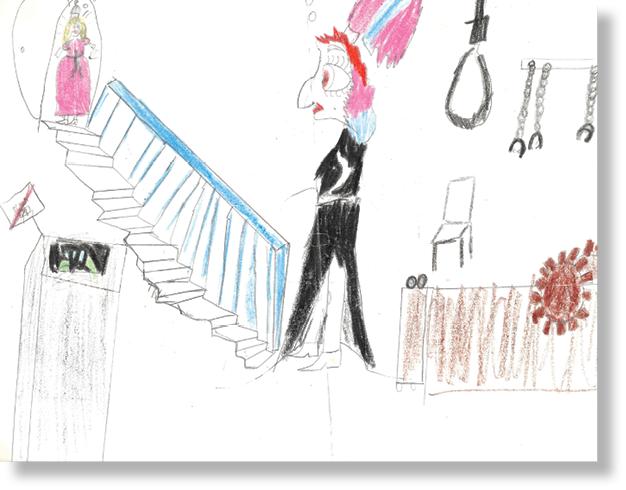

Figure 1-24:Drawing with markers

Some children who prefer markers overwhelmingly and consistently will become children who need certainty and control over events, and will often express anger (at themselves and at the page) if they haven’t managed to draw as accurately as they had intended.

Using markers requires greater manipulative skill, and stresses color variety over working deep into the page. Therefore, they will be preferred by children with a strong need for neatness as an integral part of the creative process.

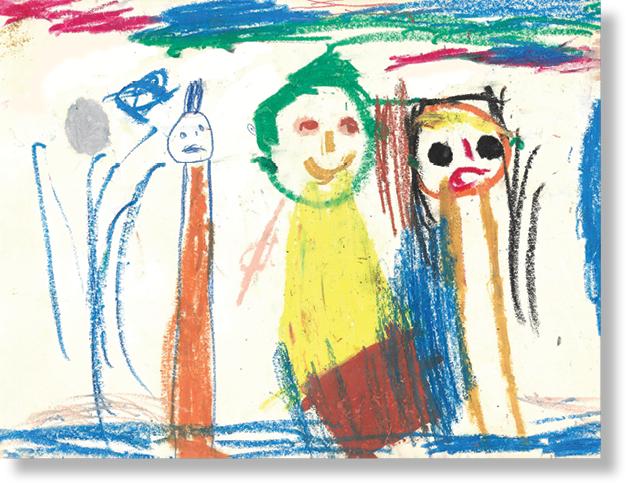

Pastel crayons introduce the child to a completely different experience. Using pastels requires greater muscular effort since the crayon has to be pressed down on the page to produce results. The child’s active contribution to the creative process makes him an integral part of the artwork. Some children pay the utmost attention to painting with pastel crayons, devoting effort and concentration to the task, while others treat the final result with indifference, show no interest in the painting and paint with low manual pressure and without attention to detail so as to “get it over with”. Essentially, pastel crayons produce less accurate paintings, such as the example in figure 1-25, and challenge the child to resolve this issue or simply enjoy the strengths of this medium.

Figure 1-25:Drawing with pastel crayons

Pastel crayons invite the child to get dirty as part of the creative process, and provide an experience of depth in addition to the color variety. Thus, children who prefer pastel will work in several layers and explore this tool’s potential to conceal and reveal.

Gouache paints, like all types of finger paints, offer the perfect sensory experience. Whether the child uses a brush or his fingers, the soft sense of paint flowing over the page offers a combined sensory-kinesthetic-emotional sensation. Naturally, painting in gouache requires the child to cope with neatness issues. Some children will refuse to use these paints at all, because they don’t want to be messy.