Полная версия

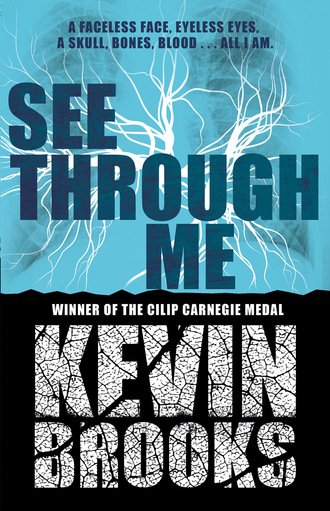

See Through Me

I thought about it . . .

It’s Finch, I told myself. You don’t need to think about texting Finch. Just do it.

I thought about it some more . . .

There was a good chance my phone wasn’t in the bag anyway. Someone could have found it – a nurse, a doctor, a paramedic – and put it away for safe keeping, or it could have just fallen out of my pocket somewhere . . . and if the phone wasn’t there, there was nothing to think about, was there? So I might as well have a look . . .

As I reached down for the bag – taking care not to pull out any of the tubes and wires attached to various parts of my body – I knew in my heart that I wanted the phone to be there, and I knew that I was going to text Finch if it was.

It was.

And I did.

When I opened the phone I saw that there was a message from Finch from three days ago.

hey kez, i’m here if you want to talk, but don’t worry if you don’t. i’m here for you anyway xxx

Even that was almost enough to break my heart.

I waited for the tingle to leave my eyes, then wrote back.

hi finch, how’s it going? sorry i didn’t write sooner, didn’t have my phone. are you ok? xxx

He replied almost immediately.

kenzie!! ha! my favourite big sis! i knew i’d hear from you this morning, I just KNEW it. i could feel it in the air

Then me.

how are you? everything ok?

Finch.

everything’s fine. but what about you? what’s going on, kez? are you all right?

Me.

not really

Finch.

is there anything i can do? do you want to talk about it?

Me.

not yet. maybe later. is that ok?

Finch.

no prob. whenever you’re ready. i’ll be here

Me.

thanks. i’ve got to go now. tired

Finch.

ok

Me.

love you xxx

Reasons . . .

I shouldn’t have sent that last message. Finch never liked it when I told him I loved him. He thought it was a bad omen, like saying a final goodbye. It made him think he was about to die.

Reasons don’t matter.

10

I’d kept myself covered up since the revelation – gown, long gloves, long socks – and I hadn’t looked at myself once. I hadn’t even taken a quick peek at anything in the hope that the transparency had gone and everything was back to normal again . . . I knew it wasn’t. I could feel it. And I knew that not looking at it wouldn’t make it go away, or make it any better . . . in fact, it might even make things worse.

But I just couldn’t do it.

I couldn’t face the hideous reality of what I’d become.

So for two days I just lay there in bed, cocooned in white in the dim grey light of the room, letting myself drift into a mindless nowhere. But then on the morning of the third day – I had no idea what day it actually was – everything became real again. I was told I was being moved to the recovery room, and that it had been decided that Dad could visit me today. It seemed a bit sudden – I was sure it was sooner than Dr Kamara had led me to believe – and I was a bit surprised that I hadn’t been asked if it was okay with me, but I didn’t say anything. Dad was going to be here at twelve o’clock, and while he was here Dr Reynolds would be sitting down with both of us to discuss my condition in detail. And that was that.

Goodbye, mindless nowhere.

Hello reality.

It wasn’t far to the recovery room. Just along a short corridor, through a secured door, then left into another corridor, and the room was tucked away at the end of a little passageway. When I got out of bed I could hardly stand up at first, let alone walk. My legs just weren’t used to it. Dr Kamara told me not to worry, that it was only to be expected after a long stay in bed, and it wasn’t a problem anyway because all I had to do was get myself into the wheelchair she’d brought with her, and she’d do the rest. I’m not sure why I wouldn’t even contemplate using the wheelchair – although I suppose it’s possible that it had something to do with Finch – but my strength of feeling must have been obvious, because Dr Kamara didn’t bother trying to change my mind. And once I’d been on my feet for a few minutes, leaning against the bed for support, my legs didn’t feel quite so wobbly anyway. I still had to stop a few times on the way to the recovery room – it felt as if I was climbing a mountain – and the two-minute journey must have taken at least fifteen minutes, but I got there in the end, and I managed to make it without falling over.

The corridors were deserted.

No doctors, no nurses, no porters . . .

No sign of anyone at all.

No windows either.

And the only thing I could hear was a faint humming sound that seemed to be coming from behind the walls.

The recovery room was nice enough. It had a small settee and a matching armchair, a table and chairs, a few cupboards, a flat screen TV, and a proper little bed (not a hospital bed). The floor was carpeted, and there was a separate bathroom (with a bath and a shower). And on the far side of the room there was a window. It was fitted with a blackout blind to keep out the daylight, and when Dr Kamara had first shown me inside, the blind was down and the room was so dark that she’d had to turn on the lights to show me around. The lights were controlled by a dimmer switch.

‘Your dad will be here at twelve,’ Dr Kamara reminded me. ‘We’ll bring him straight here when he arrives, okay?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Is there anything you need before I go?’

Yeah, I thought, I need to not be here, I need to not be a monster, I need my ordinary life back . . . my shitty old ordinary life . . .

‘I’m fine, thanks,’ I told her.

I don’t get people sometimes. I don’t understand how their minds work. Take Dr Kamara, for instance. I’d thought at first that she was the most compassionate of the three doctors, the most perceptive, the one with the most understanding. But when I’d asked her about niqabs and burqas that time – whether or not non-Muslims could wear them – I got the impression that I’d offended her in some way, and the only explanation I could think of was that she’d thought I was only asking her because I’d assumed she was a Muslim, and that I’d based that assumption purely on her appearance and the fact that she had an ‘Asian-sounding’ name. Either that or she was a Muslim, and the idea of me wearing a niqab or a burqa was somehow offensive to her faith.

Whatever the reason, I just didn’t get it.

I didn’t say anything though. And I didn’t mention niqabs or burqas again either.

But that didn’t mean I’d changed my mind.

I still wasn’t going to let my dad see my skull.

It wasn’t just that I didn’t want to put Dad through the ordeal of trying to pretend that his daughter wasn’t repulsive, or that I didn’t want him to be so traumatised that he wouldn’t be able to cope with things anymore – although, for Finch’s sake, that was something I was desperate to avoid – I also had my own selfish reasons for not wanting Dad to see my faceless face. It felt bad enough knowing how I looked to the doctors, but they were doctors, and although they still couldn’t help staring at me now and then – their professional integrity overcome by the sheer freakishness of my condition – they were, for the most part, as restrained and objective as they could be. They were doctors, and for some reason we’ll reveal things to doctors that we wouldn’t dream of sharing with anyone else.

But my dad wasn’t a doctor.

He was my dad.

And I knew he wouldn’t be able to hide his repulsion if he saw the horror of my see-through head . . . and I didn’t think I could live with that. I mean, imagine how you’d feel if your dad (or your mum) were so revolted by your appearance that they couldn’t look at you without grimacing in disgust . . .

It would tear you apart, wouldn’t it?

It would turn your world upside down.

‘You can get changed now if you want,’ Dr Kamara told me, putting the carrier bag full of clothes on the settee. ‘You don’t have to,’ she added. ‘You can wait until your dad’s brought some fresh clothes if you want, or if you feel more comfortable keeping the gown on . . . it’s entirely up to you.’

It wasn’t a difficult decision to make. I knew that nothing could make me look normal, but there were still certain things that could make me look a tiny bit less abnormal.

There was nothing normal about the gown.

There was something normal about my clothes.

I turned the lights down low, then went over and sat down on the settee next to the carrier bag. I wasn’t looking forward to getting changed – it meant exposing my body again, and even in the lowest light I was still going to see stuff I didn’t want to see – and for a moment or two I wondered if I could do it with the sleep mask on. It would obviously be quite awkward, but it certainly wasn’t impossible. The only thing was . . .

It didn’t feel right.

I shouldn’t have to be scared of myself.

And even if I was, I didn’t have to be so pathetic about it.

I picked up the carrier bag, placed it on my knees, and reached inside.

The first thing I pulled out was something that shouldn’t have been there. When I’d taken my phone out of my hoodie pocket the other day, the hoodie had been at the top of the bag, and I’d put it back in the same place. But now there was something else on top of it, and I knew it wasn’t mine. It was a smallish polythene bag, and inside it was a pair of sunglasses and a folded-up headscarf. The sunglasses were fashionably large, the kind that celebrities wear, and the lenses were really dark. The headscarf was made from some kind of silky black material.

Dr Kamara . . .

The sunglasses and scarf had to be from Dr Kamara.

Maybe I hadn’t offended after all . . . or maybe I had, but she’d forgiven me. Or maybe it was just me . . .

I don’t get people.

I really don’t.

I opened up the headscarf and held it out in front of me. I didn’t know if it was a hijab or just an ordinary headscarf – I didn’t know the difference, to be honest – but it didn’t matter. It was easily big enough to cover my whole head. And the sunglasses would cover my eyeless eyes.

Twenty minutes later I was standing in front of the bathroom mirror, looking myself over for about the hundredth time. From the neck down, I looked just about normal – pumps, leggings, skirt, T-shirt, hoodie. The only slight oddity was the white gloves on my hands and the white socks on my feet. From the neck up though, I didn’t look normal at all. I’d never even tried on a headscarf before, let alone had to cover my entire head with one, and it wasn’t just a matter of making sure that everything was covered up either. I had to make sure that it stayed covered up, which meant working out how to wrap the scarf round my head in such a way that it wouldn’t come undone.

It took quite a while, but I got there in the end.

And when I put the sunglasses on and pulled up my hood, tightening the drawstring to fix it firmly around my wrapped-up face, every inch of my see-through head was safely hidden from sight.

I looked ridiculous.

But that was okay.

It was the price I had to pay for not looking hideous.

I took out my phone and checked the time. It was 11.46. Not long to go now. As I went back into the room and sat down on the settee, I could feel my heart thumping against my ribs.

11

Dad was never the same after Mum died. It’s hard to explain how he changed – partly because I can’t really remember how he was before, so I don’t have anything to compare him to, and partly because it was the kind of change that’s very easy to hide. Outwardly he barely changed at all. If you’d asked any of his friends to describe him, they’d have told you that apart from the heartache of losing his wife, he was just the same old Barry Clark.

But he wasn’t.

And Finch and I knew it.

We could never quite work out what it was – whether there was something missing from him, or there was something about him that hadn’t been there before – but we knew, without doubt, that it was all about Mum.

She died very suddenly.

Dad always maintained that she was absolutely fine when she went to bed that night. She wasn’t ill – she’d never had a serious illness in her life – and there was nothing to suggest there was anything wrong with her. She looked well. She hadn’t complained of anything – headache, stomach ache, excessive tiredness – she’d just gone to bed in exactly the same way she always did. Setting the alarm for seven-thirty in the morning, reading a book for half an hour, then turning off the light and going to sleep.

Dad said he couldn’t remember who’d turned off the alarm in the morning. He remembered it going off, but he couldn’t recall if Mum had turned it off or if he’d leaned over her and turned it off himself. He thought he must have gone back to sleep again then, because the next thing he knew it was nearly eight o’clock, and if he didn’t get a move on he was going to be late for work. Mum was lying on her side, facing away from him, and he just assumed she was still asleep. It was a Wednesday, Mum’s day off work (she’d set the alarm so she’d be up in time to see us off to school), so Dad decided to let her sleep in.

We were all a bit late that morning, so when Dad told us that Mum was having a lie-in, we were too busy rushing around to give it any thought. All we were thinking about was getting our stuff ready and grabbing something to eat and – in Dad’s case – guzzling down a cup of coffee and trying to find his car keys.

Dad and Finch left the house first (Dad was dropping him off at school on his way to work), and I left a few minutes later. It wasn’t until I’d got to the bus stop that I realised I hadn’t said goodbye to Mum. None of us had. But I told myself it was okay. She was having a lie-in, wasn’t she? It wouldn’t have been fair to wake her up just to say goodbye.

If only I’d known . . .

If only.

Dad and Finch usually got home before me, but that day Dad was taking Finch to the opticians after school, so I got home first. The house was quiet. I called out to Mum – but only in a casual are-you-there? kind of way – and when she didn’t answer, I didn’t think anything of it. She’d either gone out somewhere or she was upstairs in the bathroom or her bedroom. I didn’t bother calling out again. I was going upstairs anyway – I needed to use the bathroom – so I’d soon find out if she was up there. And if she wasn’t, she wasn’t . . .

It was no big deal.

Nothing to worry about.

The bathroom was at the far end of the landing, and Mum and Dad’s bedroom was halfway along, and as I headed along the landing towards the bathroom I was slightly surprised to see that their bedroom door was shut. They usually only closed it at night . . .

I nearly didn’t do anything.

It was only a closed door . . .

There was probably a perfectly reasonable explanation for it.

I very nearly just walked on past and carried on heading for the bathroom.

But I didn’t.

I don’t know what it was that made me stop. Just a feeling, perhaps . . . an instinctive sense that something was wrong . . .

I don’t know.

I called out to her again – ‘Mum?’ – and although I tried to sound as carefree as possible, as if somehow that would make everything okay, my voice sounded strained. I cleared my throat, stepped closer to the door, and tried again . . . louder this time – ‘Mum! Are you in there? MUM!’ – not caring anymore how I sounded, just desperate for Mum to reply.

But she didn’t.

I gave it one last go, this time knocking hard on the door as well as calling her name, but even as I was doing it I knew in my heart it was a waste of time. I knew what I had to do. And I knew I just had to do it.

I reached for the handle, opened the door, and stepped through into the bedroom.

The curtains were closed.

Mum was in bed.

She was lying on her side, under the duvet, her head just visible, facing away from me . . .

Very quiet, very still.

‘Mum?’ I said softly.

Nothing.

I couldn’t move . . . I didn’t want to move. As long as I stayed where I was – just inside the doorway – I wasn’t close enough to the bed to see Mum’s face, and if I couldn’t see her face, I wouldn’t know for sure why she was just lying there like that . . .

I didn’t want to know.

If I didn’t know, it couldn’t hurt me.

I stood there barely breathing for maybe a minute or so, hoping against hope that if I kept perfectly still and didn’t make a sound I’d hear something familiar in that unearthly silence – a breath, a cough, a sniff, a sigh . . . anything at all . . .

There was nothing.

Something made me move then. Something . . . I don’t know what it was. What makes you do anything? My mind had shut down now, and as I crossed over to the bed I wasn’t thinking or feeling anything. It was as if I was set on automatic – just walking, moving, doing what I was doing . . . moving round the foot of the bed . . . then along the side where Mum was lying . . . seeing her head on the pillow . . . seeing her face . . . her lifeless eyes, staring at nothing . . .

I collapsed then, slumping down onto the bed, and I took her in my arms and held her tightly, cradling her head to my chest.

She was horribly cold . . .

Cold and stiff.

Whenever I think of Mum now, that’s what I remember – that terrible cold deadness. I feel it in the palms of my hands.

The doctor who examined Mum’s body couldn’t confirm a cause of death, and when the coroner ordered a post-mortem, the pathologist didn’t find anything either. No heart problems, no cancer, no blood clots . . . no drugs, no alcohol, no poison . . . nothing at all that could have led to her death. I remember someone saying at the time that ‘it was as if her life was just suddenly switched off’. The only thing the post-mortem established was that Mum probably died some time between one o’clock and eight o’clock that morning.

The coroner opened an inquest into Mum’s death, and during the investigation we were all asked lots of questions. Dad was also interviewed by the police, both at home and at the police station.

The inquest took a long time, but in the end it all came to nothing. There was still no reasonable explanation for Mum’s death. No one could say how she died, or why, and the coroner had to return an open verdict. The cause of death was officially recorded as ‘unknown’.

There were a lot of things I didn’t understand at the time – and even now I’m not sure I know the whole story – and I didn’t (and still don’t) fully understand how some of these things affected Dad. I know he was really angry about the police getting involved – he flatly refused to even speak to them at first – and it was around that time that he had a blazing row with Nan, my mum’s mother. I found out later what it was all about, but all I knew then was that he’d banned her from our house, and Finch and I weren’t allowed to see her anymore.

There was a period when I think Dad blamed himself for Mum’s death. If only he’d checked on her that morning, if only he hadn’t left without saying goodbye, if only . . . if only . . . if only . . .

But at some point, I think he stopped feeling guilty. I could be wrong, of course – it wouldn’t be the first time – but as time went on, and things kept going from bad to worse, I got the feeling that Dad started blaming Mum for everything. He never actually said as much, but by this time he very rarely spoke about her anyway. If me or Finch asked him something about her – or even just mentioned her – his face would go blank, and he’d either just walk away or change the subject and carry on as if nothing had happened.

On the day after the first anniversary of her death, he went round the house collecting all her stuff together – clothes, books, jewellery, shoes, boxes full of old photographs . . . anything that was hers and hers alone – then he loaded it all up in the car and drove off without telling us where he was going. When he got back home, the car was empty.

I really don’t know what was going on his head, but there were times when the truth was so clear in his eyes that his feelings about Mum were unquestionable.

It was all her fault.

If she hadn’t died, he wouldn’t have been maligned and humiliated by the police, and he wouldn’t have had to waste his time dealing with Nan, and he wouldn’t have had to sacrifice everything now that Finch was so ill . . . he wouldn’t have had to give up his job, and he wouldn’t have had to dedicate his whole life to caring for his son . . .

And now here I was, adding yet another burden to his shoulders, and giving him yet another thing to blame on Mum.

But, like I said, I could be wrong.

And even if I’m not, you can’t help how you feel, can you? Wherever your thoughts and feelings come from – your heart, your mind, your soul – it’s just as much beyond your control as everything else that makes you what you are. Blood, enzymes, hormones, proteins, cells, organs, neurochemicals . . .

You don’t control any of it.

It controls you.

12

Dad was late.

It was gone twelve-thirty when he finally arrived – a hesitant knock on the door, a muttered voice – ‘Kenzie? It’s me . . .’ – and as I got up from the settee, intending to let him in, the door opened just enough for him to poke his head through.

‘All right if I come in?’ he said.

He was doing his best to smile at me, and I knew it was a genuine attempt rather than something he was forcing himself to do, but he just didn’t have it in him. As he stepped through the door and closed it behind him, I could see the turmoil in his eyes and the nervous hesitancy in his movement, and I couldn’t help feeling sorry for him. Imagine how he must have felt – facing up to his mutant daughter, her disfigurement hidden beneath a ludicrous disguise . . . not knowing what to do, or what to say, or where to look, or how to feel . . .

Who wouldn’t be bewildered by all that?

He was carrying a holdall in his hand, and as he turned from the door and started speaking to me he couldn’t stop fidgeting around with it – swinging it against his leg, twisting the hand straps, bobbing it up and down . . .

‘I’m sorry I’m late, Kenzie,’ he said. ‘We’ve been having a lot of problems with the carers, something to do with their shift patterns or something, and then when I did get going there was an accident on the A13 –’

‘It’s all right, Dad,’ I told him. ‘It doesn’t matter.’

‘Where do you want this?’ he said, holding up the bag. ‘It’s your clothes and stuff, books, soap, toothbrush . . . I wasn’t sure what to bring . . .’

He was talking too quickly, almost jabbering, and his eyes were all over the place. He kept trying to look at me, but there was nothing of me to see – my face wrapped up, my eyes masked by sunglasses . . . and I realised then that he had no way of knowing how I was. He couldn’t see if I was crying, smiling, angry, sad . . .

But he couldn’t see my faceless skull either.

And that’s how it had to be.

‘Where do you want me to put it?’ he repeated, still holding the bag, his eyes still darting around the room. ‘On the bed?’

‘Yeah, anywhere, Dad . . . it doesn’t matter.’

‘I’ll put it on the bed.’

He went over and put the holdall on the bed, and for a second or two he just stood there, facing away from me, not saying a word. His head was slightly bowed down, as if he was staring at the floor, but after a few moments he slowly straightened up, and then – to my surprise – he turned round, came over to where I was standing, and put his arms around me.