Полная версия

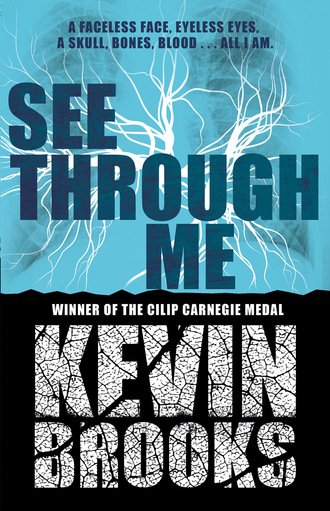

See Through Me

He’d seen enough though. Enough to believe the woman when she told him what she’d seen – her sombreness deserting her as she jabbered away at him, frantically waving her hands about and pointing at my head – and enough for him to realise that drastic steps had to be taken.

An hour or so later I was wheeled out of the room, then along the corridors again, into the lift, down to the ground floor, and out into a waiting ambulance.

3

I’m not sure if I was given a sedative of some kind before leaving BPG, or if I was just so tired that I couldn’t keep my eyes open. But whatever the reason, I slept for most of the ambulance journey. It wasn’t a normal sleep. It was that twilight sort of sleep you get when you’re just dozing off – neither fully asleep nor fully awake – and you can’t tell if the things you’re hearing and seeing in your mind are real or not. It doesn’t usually last very long – you either fall asleep completely or wake up – but this time the twilight didn’t go away. I could hear the wail of the siren, and I could see the sound of it too. It was a series of thin flat sheets, all of them electric blue, their flatness gently undulating as they sliced through a pure black emptiness. And I could hear, and sometimes see, the people in the back of the ambulance with me. One of them was the senior doctor, the other one looked just like my mum.

My mum died six years ago. I was twelve at the time, and Finch was eight.

The children we were died with her.

I know now that the ambulance journey didn’t take all that long – with the siren on and the emergency lights flashing it probably only took about half an hour – but my senses were so mixed up that minutes seemed like hours and hours seemed like minutes. For all I knew, I could have been in the ambulance for days.

The place I was taken to seemed like an ordinary hospital at first – a big grey building, long white corridors, people in hospital-type clothing – and it wasn’t until I’d been there for a while, and my strange sleepiness had begun to wear off, that I started to realise there was something different about it. The room I was put in, for example, had all the same stuff as my room at BPG – same hospital bed, same monitors and equipment, same tubes and wires all over the place – but it also had a CCTV camera on the wall, the lens pointing directly at me, and a swipe-card entry system on the door. If you didn’t have a key card, you couldn’t get in or out.

And another thing I realised was that I hadn’t seen any other patients. Or visitors. Just medical staff – doctors, nurses, porters . . .

I tried to think about it, to work out what it meant, but I was starting to feel really strange again, and I kept forgetting what I was thinking about. It was a different kind of strangeness now. Worse, far more intense. My whole body, everything about me, felt alien. Even the pain felt wrong. It was like a living thing growing inside me . . . a clawing spread of living hurt eating its way through my flesh. My skin felt sick – clammy, raw – and I could feel my muscles beginning to twitch. It wasn’t too bad at first – just a faint kind of fluttering beneath the skin, mostly in my arms and legs – but it rapidly got worse, and in no time at all my entire body was shuddering so violently that the bed was rattling beneath me. I tried to grab hold of something, desperately trying to steady myself, but my arms didn’t belong to me any more . . . they were just there, shaking uncontrollably at my sides . . .

Something happened in my head then.

I still can’t remember exactly what it was.

A sound, perhaps . . . but not a sound.

The feeling of a sound.

A flash of black lightning?

No . . .

I don’t know.

All I can really remember is a sense of people hurrying into the room, a blur of voices – urgent but calm – then firm hands taking hold of my convulsing body. I couldn’t see who it was, because for some reason I couldn’t see anything at all. I didn’t understand it, but it was too much to think about. I was still shuddering and twitching, still wracked with pain . . .

I closed my eyes and tried not to feel anything.

After the shaking had eventually stopped, and after I’d opened my eyes and shut them again for at least the fiftieth time, I finally had to accept the truth.

I was blind.

I lost track of time after that.

I lost track of everything.

I remember floating – blind, paralysed, senseless, timeless – and I remember the hurt inside me, its blunt teeth grinding and wrenching . . . and the cold sickness in my bones . . . and the shearing pain of skin being stripped from flesh . . .

And I remember the nothingness too.

The nothingness of not knowing.

I didn’t know who I was or where I was or what was going on . . . I didn’t even know what I was. All I knew was the hurt. But at the same time there was something in an unknown part of me, something I can’t explain, that somehow knew – or at least sensed – what was happening to me. It knew there were at least two doctors working on me all the time – examining every inch of me, taking samples, measuring, scanning, listening, talking. It could sense their hands on my skin, their probing instruments, the stinging stab of their needles . . . and it knew all these things for what they were. But there were other things happening to me, other sensations, that it sensed without understanding. A soft and slightly ticklish feeling on the top of my head and the back of my neck . . . and later, in the same place, the gentle brushing of a hand. Movement . . . quiet and smooth . . . a rubbery hum . . . a machine starting up . . . something spinning around my head . . . the rapid whirr of an electric wheel . . . then silence again, and movement again . . . quiet and smooth . . . a rubbery hum . . . then more silence. A covering . . . a feeling of lightness being laid over my skin . . . arms, legs, body, face . . . a shroud so delicate it’s almost weightless . . . and then the same silky lightness being slipped onto my hands . . .

I slept and dreamed.

My body dreamed.

It was a dream of presence – no sight, no sound – just a knowing. It was in my every element – bone, blood, flesh – the knowing and the presence together. It was one thing and many things.

It was me – and somehow the possibility of something of me . . .

It was Finch – connected and disconnected . . .

And Mum – alone in a sad silence . . .

And her mum, my nan – old and blind, her blindness trailing through Mum’s heart to touch upon my eyes . . .

And there were others too – uncountable others, nameless but not unknown . . . mothers and daughters, mothers and daughters . . . a son, a brother . . .

Mothers and daughters.

They were me.

And I was them.

It was the silent scream that finally woke me.

I was dreaming a dream of spinning and whirling, going faster and faster all the time, and there was something inside me – a feeling in my chest – screaming silently for the spinning to stop. It was a feeling of life, this screaming thing, and the spinning was tearing it apart.

It didn’t want to die.

It screamed, desperate to break the silence.

The spinning roared.

The scream swelled, filling my lungs, my chest, my throat . . .

I couldn’t breathe.

I opened my mouth and screamed.

It wasn’t much of a sound – more like a strangled whimper than a scream – but it was enough to break me out of the dream and jerk me awake. I woke instantly, sitting bolt upright and gasping for breath, and I knew straight away that everything had changed. The different world had gone. There was no invisible barrier, no distortion, no sense of otherness.

I could hear normally again – voices, urgent movement, someone saying my name . . .

And I could see.

The room was dim, the light pale and low, but I could see my immediate surroundings. I could see the grey-haired man standing beside me, his hand reaching gently for my shoulder, and I could see the olive-skinned woman on the other side of the bed, leaning over to straighten out the bed sheet. The sheet wasn’t covering my feet, both of which were covered up by long white socks, and I could see that the sock on my right foot had slipped down and was half hanging off . . .

I could see.

And in the moment before the sheet was pulled down over my feet, the moment before the grey-haired man began easing me back down to the bed, I saw a flash of red . . .

The red of meat.

4

‘Can you hear me, Kenzie? Can you understand what I’m saying?’

I was lying in the bed, staring up at the grey-haired man and the olive-skinned woman as they stood there looking down at me. I felt utterly exhausted. Bone-tired and drained. And my body was aching all over. It was the kind of ache you get when your body’s been through a battering – dull and bruised, wearying . . . but not painful.

I didn’t hurt anymore.

‘Kenzie?’ the woman said. ‘Can you tell us how you’re feeling?’

I had no pain, no sickness, no fever. But I knew I wasn’t right. My skin felt wrong – cold, but not cold . . . clammy, shivery, prickly, raw . . . and the wrongness wasn’t just on my skin, it was in it . . . inside me . . . beneath the skin.

The top of my head felt different too.

And I seemed to be wearing long white gloves that reached up to my elbows . . .

‘If you can hear us, Kenzie,’ the grey-haired man said, ‘just nod your head, okay? We need to know –’

‘What’s the matter with me?’

My voice was a croaky whisper.

The man and the woman glanced at each other for a moment – sharing a look that I didn’t understand – then they both turned back to me.

‘Hi, Kenzie,’ the man said to me, smiling his doctor’s smile. ‘I’m Doctor Reynolds, and this is my colleague –’

‘What’s the matter with me?’ I repeated. ‘What’s going on? Why am I –?’

‘We’ll explain everything soon,’ he said calmly. ‘Your dad’s on his way here now. He won’t be long. We’ll tell you as much as we can when he gets here. In the meantime –’

I sat up suddenly, taking them both by surprise, and before they could do anything to stop me, I threw off the bed sheet, grabbed the hem of my gown, and yanked it up to reveal my feet and legs.

I think something in me knew what I was going to see, but however much I thought I knew, it was never going to make any difference. Nothing on earth could have prepared me for what I saw that day.

My feet and lower legs were covered by the knee-high white socks that I’d seen before, but with the gown pulled up to the tops of my thighs, the upper halves of my legs were visible. But they weren’t my legs anymore. They weren’t real . . . they couldn’t be. They were skinless, stripped . . . a gruesome vision of naked red muscle and sick-yellow globs and pinkish-white gristly things . . . and something of bone . . . two half-hidden white domes, one on each knee . . .

Knee caps.

No . . .

It couldn’t be.

I moved my right leg, cautiously raising my knee . . .

The skinless vision responded.

It was my leg.

That thing of meat and bone was me.

I closed my eyes, unable to look anymore . . . but nothing happened. I could still see. I could see through my closed eyes . . .

See through . . .

It couldn’t be real.

But it was.

I’m not sure what happened then. I vaguely remember a feeling of absolute blankness – no thoughts, no emotions . . . just a stupefied nothingness – but I don’t know if it was a natural reaction to the shock, my mind and body shutting me down, or if one of the doctors had given me something to calm me down. Either way though, the next thing I can remember is sitting up in bed, with the olive-skinned woman standing to my right, Doctor Reynolds perched on a chair to my left, and a woman I’d never seen before sitting in a chair beside him. She had short blonde hair and an eyebrow stud. An open notebook was resting in her lap.

The room was still very dim, and as I gazed slowly around – getting my first proper look at the place – I realised there weren’t any windows. There were lights fitted into the ceiling – four flat squares of whitish glass – but they were all turned off, and apart from the pale glow of the monitor screens, the only source of light I could see was a small LED panel fixed to the far wall. I stared at it for a moment, then closed my eyes . . .

I could still see it.

Nothing had changed.

‘How are you, Kenzie?’ I heard Doctor Reynolds say.

I turned and looked at him. I didn’t know what to say.

‘Your dad’s had to go back home, I’m afraid,’ he said, leaning forward in his chair. ‘There was a problem with your brother –’

‘What kind of problem?’ I said. ‘Is Finch all right? Has something happened to him?’

‘No, he’s fine,’ the doctor assured me. ‘It was just something to do with his carer, apparently . . . some kind of mix-up. Your dad had to go back to sort it all out.’

‘But Finch is definitely okay?’

He nodded. ‘And your dad’s hoping to get out here tomorrow.’

‘Does that mean you’re not going to tell me anything until then?’

Doctor Reynolds glanced at the woman beside him. She’d been watching me closely while I’d been talking, and at one point she’d scribbled something down in her notebook. She was still looking at me now – a serene steadiness showing in her eyes – and after a few moments’ silence, she leaned to one side a little, resting an elbow on the arm of the chair, and spoke to me in a measured tone.

‘Do you want to wait for your dad before we start telling you anything?’ she asked, her eyes fixed on mine.

‘Not if I don’t have to.’

‘Do you mind if I ask why?’

‘I can see inside myself,’ I told her. ‘I can see my own muscles, my bones . . . and when I close my eyes –’ I closed my eyes ‘– I can still see you.’ I opened my eyes and stared at her. ‘If all that was happening to you, would you want to spend another whole day waiting to find out what’s going on?’

The woman didn’t say anything for a while, she just sat there, gazing thoughtfully into my eyes. Eventually, she turned to Doctor Reynolds and gave him the slightest of nods. He nodded back, glanced across at the olive-skinned woman – who was adjusting something on one of the monitors – then he turned his attention back to me.

‘Right then, Kenzie,’ he said. ‘Let’s start with the simple stuff.’

5

The ‘simple stuff’ didn’t take very long. Dr Reynolds introduced himself again – his first name was John – and then he told me who the two women were. The olive-skinned woman was Dr Miriam Kamara, and the other one was Dr Shelley Hahn. Dr Reynolds then went on to explain where I was, and why I’d been brought here.

‘You’re in a specialised medical facility called the RDRT Centre,’ he told me. ‘RDRT stands for Rare Disease Research and Treatment. We’re about twenty miles north of London here, so you’re not too far from home. I’m the Centre’s Clinical Director, and Dr Kamara is Head of Physical Care.’

I looked at Dr Hahn.

‘I’m a clinical psychologist,’ she told me. ‘I work with the Centre’s Recovery and Evaluation team.’

I nodded.

She smiled.

Dr Reynolds went on. ‘We’re not the only Rare Disease Centre in the country,’ he explained, ‘but we’re the only one that undertakes both research and specialised treatment. Our treatment capacity is quite limited – we only have four special care rooms, including this one – but we only take on the very rarest of cases, so we don’t actually need any more beds. At the moment you’re our only patient.’

He paused for a second, sipping water from a plastic cup.

‘Any questions so far?’ he asked me.

‘Yeah,’ I said. ‘When are you going to tell me what’s wrong with me?’

He started by telling me what wasn’t wrong with me, which as far as I could tell was pretty much everything. I wasn’t suffering from a virus, or any kind of infection. My blood count was fine. Kidney function, liver function, heart . . . all okay. Toxicology test negative. X-rays and scans – CT and MRI – perfectly normal . . .

‘Some of your test results showed slightly abnormal readings,’ Dr Kamara said, taking over from Dr Reynolds, ‘but most of these can be put down to highly elevated levels of stress. In fact, given what you’ve been through, I’d be worried if you didn’t show signs of stress.’ She glanced at Dr Hahn, then turned back to me. ‘There are still a lot of tests that we haven’t done yet,’ she continued, ‘and we’re still waiting for the results of some we’ve already done, but so far it seems as if . . .’

She hesitated, her voice trailing off, and she looked over at Dr Reynolds.

‘How do you feel at the moment, Kenzie?’ he asked me, getting out of the chair and coming over to the bed.

‘Why can’t you just tell me –?’

‘I’m going to tell you everything,’ he said, moving aside to let Dr Hahn stand beside him. ‘But before I start, I need to know how you’re feeling.’

It’s hard to describe something that isn’t like anything else. If there’s nothing to compare it to, and there aren’t any words for it, it’s impossible to say what it’s really like. All you can do is get as close as you can. So that’s what I tried to do. But even after I’d done my best to describe the weird feeling in my skin – the uncold coldness, the clamminess, the tingling rawness of freshly scraped flesh – I knew I’d got nowhere near it.

‘Does it hurt?’ Dr Reynolds asked me.

‘No, not really . . . it just feels kind of . . . I don’t know . . .’

‘Unpleasant?’

‘A little bit, yeah.’

‘But it’s not painful.’

I shook my head. ‘It just feels wrong.’

He was looking closely at me now, his head angled to one side as he gazed intently at the side of my face, and as he leaned in a little closer – a sense of wonder showing in his eyes – I could feel the anger growing inside me. I’d had enough of this now – being gawped at, studied, examined, like I was some kind of experiment or something. I needed the truth . . . I needed to see myself . . . I needed to know . . .

I don’t know what I would have done if Dr Hahn hadn’t realised I was getting upset and given Dr Reynolds a discreet little nudge. Part of me was so desperate to see myself, to see the dreaded truth, that all I wanted to do was push Dr Reynolds away and rip off my gown and the long white gloves . . .

But another part of me was simply too terrified to do anything.

Dr Reynolds had responded to Dr Hahn’s nudge now, realising his mistake and straightening up so he wasn’t staring right into my face anymore.

‘Sorry, Kenzie,’ he said. ‘I didn’t mean –’

‘Help me,’ I muttered. ‘Please . . . just help me.’

‘I’m afraid there’s only one way to do this, Kenzie,’ Dr Reynolds said. ‘I could tell you what’s happened to you, and I could try to prepare you for what you’re about to see, but nothing will really mean anything to you until you actually see it. Does that make sense?’

I nodded.

‘And besides,’ he added, ‘you’ve already got at least some idea of what to expect, haven’t you?’

I remembered the flash of red . . . skinless, stripped . . . and the skull in the bathroom mirror . . . faceless bone, grinning teeth . . .

What did I expect?

I don’t know.

I think I was probably hoping rather than expecting . . . hoping that what I was expecting proved to be wrong.

‘Are you okay to go ahead with this, Kenzie?’ Dr Hahn said.

‘Yeah.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Yeah.’

‘If you want to stop at any point, for any reason, just tell us. All right?’

‘Yeah.’

She smiled at me, then turned to Dr Reynolds and nodded.

‘Could you adjust the lighting, please, Miriam?’ he said to Dr Kamara.

She went over to a control panel by the door and pressed one of the buttons. The LED light on the far wall dimmed, and the already gloomy room grew even darker.

‘Is that enough?’ she asked Dr Reynolds.

He looked at me, studying my face for a moment, then nodded to himself.

‘That’s fine,’ he said. ‘Just right.’

The light was so dim now that it was hard to see anything clearly, and as Dr Kamara came back over to the bed, and I gazed around at the monitor displays glowing palely in the dimness, I couldn’t make any sense of it.

‘Is that going to make any difference?’ I said to Dr Reynolds.

‘The light?’

‘Yeah. I mean, turning the light down isn’t going to change anything, is it?’

‘Well, actually . . .’ He paused, hesitating. ‘Look, I’m not trying to hide anything from you, Kenzie, it’s just that certain things are going to be a lot easier to explain, and easier to understand, when you know a bit more about your condition. I realise it’s all very confusing, but if I tried telling you now why we’ve dimmed the light, it would confuse things even more. You’ll find out soon enough though, and I give you my word on that. But for now I think it’s probably best if we concentrate on one thing at a time. Is that okay with you?’

I told him it was.

Then he asked me if I was ready.

And I told him I was, even though half of me wasn’t.

‘Miriam?’ he said.

As I turned to Dr Kamara, I saw that she was holding a clean white pillow in her hands.

‘I’m going to put this on your lap, Kenzie,’ she said. ‘Is that all right?’

I nodded.

‘You’ll have to move your hands, please.’

My white-gloved hands were loosely clasped together in front of me. I moved them out of the way, laying my arms at my sides, and Dr Kamara leaned across and carefully placed the pillow on my lap.

‘Is that okay?’ she asked. ‘Comfortable?’

‘Yeah . . .’

‘Good. Now all I want you to do is lay your left hand on top of the pillow. Like this . . .’

She showed me, leaning over and positioning her hand and lower arm along the length of the pillow, her palm face down.

‘All right?’ she said.

‘Yeah.’

She removed her hand and straightened up, and I copied what she’d done – left arm bent at the elbow, hand and lower arm resting on the pillow, palm face down. There was an ugliness to the way it looked – shrouded in the alien whiteness of the glove and the sleeve of the gown . . . it looked like something sick and dying.

‘I’m just going to roll up your sleeve now,’ Dr Kamara said, leaning over me again. ‘Could you lift your arm for me, please? Just a little bit . . . that’s it.’

She carefully rolled up the sleeve, stopping a few inches below my elbow – so my lower arm was still covered by the long white glove – then she gently replaced my hand on the pillow, straightened up again, and looked across at Dr Reynolds.

‘I’m going to show you your hand and your arm now, Kenzie,’ he said to me. ‘I’ll do it very slowly, okay? I’m going to lower the sleeve of the glove just a few inches at a time. If at any point you want me to stop, or you want to be covered up again, just tell me. I won’t do anything you don’t want me to. Is that all okay with you?’

I nodded.

‘Any questions before we start?’

‘Do you want me to hold out my arm or anything?’

He shook his head. ‘Just keep it on the pillow, right where it is.’

‘Okay.’

My voice sounded strange – weak and shaky, breathless, the words getting caught in my throat . . .

I watched in silence as Dr Reynolds made a few final adjustments to his position beside the bed, making sure he could comfortably reach my arm with both hands, and then – seemingly satisfied – he glanced round at the other two, gave them a nod, and turned back to me.