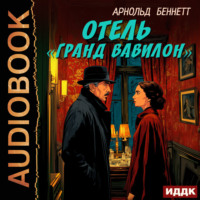

Полная версия

Отель «Гранд Вавилон» / The Grand Babylon hotel

‘Oh,’ said Racksole lightly, ‘it doesn’t matter. Shall we say from to-night?’

‘As you will. I have long wished to retire. And now that the moment has come—and so dramatically—I am ready. I shall return to Switzerland. One cannot spend much money there, but it is my native land. I shall be the richest man in Switzerland.’ He smiled with a kind of sad amusement.

‘I suppose you are fairly well off?’ said Racksole, in that easy familiar style of his, as though the idea had just occurred to him.

‘Besides what I shall receive from you, I have half a million invested.’

‘Then you will be nearly a millionaire?’

Felix Babylon nodded.

‘I congratulate you, my dear sir,’ said Racksole, in the tone of a judge addressing a newly-admitted barrister. ‘Nine hundred thousand pounds, expressed in francs, will sound very nice—in Switzerland.’

‘Of course to you, Mr Racksole, such a sum would be poverty. Now if one might guess at your own wealth?’ Felix Babylon was imitating the other’s freedom.

‘I do not know, to five millions or so, what I am worth,’ said Racksole, with sincerity, his tone indicating that he would have been glad to give the information if it were in his power.

‘You have had anxieties, Mr Racksole?’

‘Still have them. I am now holiday-making in London with my daughter in order to get rid of them for a time.’

‘Is the purchase of hotels your notion of relaxation, then?’

Racksole shrugged his shoulders. ‘It is a change from railroads,’ he laughed.

‘Ah, my friend, you little know what you have bought.’

‘Oh! yes I do,’ returned Racksole; ‘I have bought just the first hotel in the world.’

‘That is true, that is true,’ Babylon admitted, gazing meditatively at the antique Persian carpet. ‘There is nothing, anywhere, like my hotel. But you will regret the purchase, Mr Racksole. It is no business of mine, of course, but I cannot help repeating that you will regret the purchase.’

‘I never regret.’

‘Then you will begin very soon—perhaps to-night.’

‘Why do you say that?’

‘Because the Grand Babylon is the Grand Babylon. You think because you control a railroad, or an iron-works, or a line of steamers, therefore you can control anything. But no. Not the Grand Babylon. There is something about the Grand Babylon—’ He threw up his hands.

‘Servants rob you, of course.’

‘Of course. I suppose I lose a hundred pounds a week in that way. But it is not that I mean. It is the guests. The guests are too—too distinguished. The great Ambassadors, the great financiers, the great nobles, all the men that move the world, put up under my roof. London is the centre of everything, and my hotel—your hotel—is the centre of London. Once I had a King and a Dowager Empress staying here at the same time. Imagine that!’

‘A great honour, Mr Babylon. But wherein lies the difficulty?’

‘Mr Racksole,’ was the grim reply, ‘what has become of your shrewdness—that shrewdness which has made your fortune so immense that even you cannot calculate it? Do you not perceive that the roof which habitually shelters all the force, all the authority of the world, must necessarily also shelter nameless and numberless plotters, schemers, evil-doers, and workers of mischief? The thing is as clear as day—and as dark as night. Mr Racksole, I never know by whom I am surrounded. I never know what is going forward. Only sometimes I get hints, glimpses of strange acts and strange secrets. You mentioned my servants. They are almost all good servants, skilled, competent. But what are they besides? For anything I know my fourth sub-chef may be an agent of some European Government. For anything I know my invaluable Miss Spencer may be in the pay of a court dressmaker or a Frankfort banker. Even Rocco may be someone else in addition to Rocco.’

‘That makes it all the more interesting,’ remarked Theodore Racksole.

‘What a long time you have been, Father,’ said Nella, when he returned to table No. 17 in the salle à manger.

‘Only twenty minutes, my dove.’

‘But you said two seconds. There is a difference.’

‘Well, you see, I had to wait for the steak to cook.’

‘Did you have much trouble in getting my birthday treat?’

‘No trouble. But it didn’t come quite as cheap as you said.’

‘What do you mean, Father?’

‘Only that I’ve bought the entire hotel. But don’t split.’

‘Father, you always were a delicious parent. Shall you give me the hotel for a birthday present?’

‘No. I shall run it—as an amusement. By the way, who is that chair for?’

He noticed that a third cover had been laid at the table.

‘That is for a friend of mine who came in about five minutes ago. Of course I told him he must share our steak. He’ll be here in a moment.’

‘May I respectfully inquire his name?’

‘Dimmock—Christian name Reginald; profession, English companion to Prince Aribert of Posen. I met him when I was in St Petersburg with cousin Hetty last fall. Oh; here he is. Mr Dimmock, this is my dear father. He has succeeded with the steak.’

Theodore Racksole found himself confronted by a very young man, with deep black eyes, and a fresh, boyish expression. They began to talk.

Jules approached with the steak. Racksole tried to catch the waiter’s eye, but could not. The dinner proceeded.

‘Oh, Father!’ cried Nella, ‘what a lot of mustard you have taken!’

‘Have I?’ he said, and then he happened to glance into a mirror on his left hand between two windows. He saw the reflection of Jules, who stood behind his chair, and he saw Jules give a slow, significant, ominous wink to Mr Dimmock—Christian name, Reginald.

He examined his mustard in silence. He thought that perhaps he had helped himself rather plenteously to mustard.

Chapter Three. At three a.m.

MR REGINALD DIMMOCK proved himself, despite his extreme youth, to be a man of the world and of experiences, and a practised talker. Conversation between him and Nella Racksole seemed never to flag. They chattered about St Petersburg, and the ice on the Neva, and the tenor at the opera who had been exiled to Siberia, and the quality of Russian tea, and the sweetness of Russian champagne, and various other aspects of Muscovite existence. Russia exhausted, Nella lightly outlined her own doings since she had met the young man in the Tsar’s capital, and this recital brought the topic round to London, where it stayed till the final piece of steak was eaten. Theodore Racksole noticed that Mr Dimmock gave very meagre information about his own movements, either past or future. He regarded the youth as a typical hanger-on of Courts, and wondered how he had obtained his post of companion to Prince Aribert of Posen, and who Prince Aribert of Posen might be. The millionaire thought he had once heard of Posen, but he wasn’t sure; he rather fancied it was one of those small nondescript German States of which five-sixths of the subjects are Palace officials, and the rest charcoal-burners or innkeepers. Until the meal was nearly over, Racksole said little—perhaps his thoughts were too busy with Jules’ wink to Mr Dimmock, but when ices had been followed by coffee, he decided that it might be as well, in the interests of the hotel, to discover something about his daughter’s friend. He never for an instant questioned her right to possess her own friends; he had always left her in the most amazing liberty, relying on her inherited good sense to keep her out of mischief; but, quite apart from the wink, he was struck by Nella’s attitude towards Mr Dimmock, an attitude in which an amiable scorn was blended with an evident desire to propitiate and please.

‘Nella tells me, Mr Dimmock, that you hold a confidential position with Prince Aribert of Posen,’ said Racksole. ‘You will pardon an American’s ignorance, but is Prince Aribert a reigning Prince—what, I believe, you call in Europe, a Prince Regnant?’

‘His Highness is not a reigning Prince, nor ever likely to be,’ answered Dimmock. ‘The Grand Ducal Throne of Posen is occupied by his Highness’s nephew, the Grand Duke Eugen.’

‘Nephew?’ cried Nella with astonishment.

‘Why not, dear lady?’

‘But Prince Aribert is surely very young?’

‘The Prince, by one of those vagaries of chance which occur sometimes in the history of families, is precisely the same age as the Grand Duke. The late Grand Duke’s father was twice married. Hence this youthfulness on the part of an uncle.’

‘How delicious to be the uncle of someone as old as yourself! But I suppose it is no fun for Prince Aribert. I suppose he has to be frightfully respectful and obedient, and all that, to his nephew?’

‘The Grand Duke and my Serene master are like brothers. At present, of course, Prince Aribert is nominally heir to the throne, but as no doubt you are aware, the Grand Duke will shortly marry a near relative of the Emperor’s, and should there be a family—’ Mr Dimmock stopped and shrugged his straight shoulders. ‘The Grand Duke,’ he went on, without finishing the last sentence, ‘would much prefer Prince Aribert to be his successor. He really doesn’t want to marry. Between ourselves, strictly between ourselves, he regards marriage as rather a bore. But, of course, being a German Grand Duke, he is bound to marry. He owes it to his country, to Posen.’

‘How large is Posen?’ asked Racksole bluntly.

‘Father,’ Nella interposed laughing, ‘you shouldn’t ask such inconvenient questions. You ought to have guessed that it isn’t etiquette to inquire about the size of a German Dukedom.’

‘I am sure,’ said Dimmock, with a polite smile, ‘that the Grand Duke is as much amused as anyone at the size of his territory. I forget the exact acreage, but I remember that once Prince Aribert and myself walked across it and back again in a single day.’

‘Then the Grand Duke cannot travel very far within his own dominions? You may say that the sun does set on his empire?’

‘It does,’ said Dimmock.

‘Unless the weather is cloudy,’ Nella put in. ‘Is the Grand Duke content always to stay at home?’

‘On the contrary, he is a great traveller, much more so than Prince Aribert. I may tell you, what no one knows at present, outside this hotel, that his Royal Highness the Grand Duke, with a small suite, will be here to-morrow.’

‘In London?’ asked Nella.

‘Yes.’

‘In this hotel?’

‘Yes.’

‘Oh! How lovely!’

‘That is why your humble servant is here to-night—a sort of advance guard.’

‘But I understood,’ Racksole said, ‘that you were—er—attached to Prince Aribert, the uncle.’

‘I am. Prince Aribert will also be here. The Grand Duke and the Prince have business about important investments connected with the Grand Duke’s marriage settlement… In the highest quarters, you understand.’

‘For so discreet a person,’ thought Racksole, ‘you are fairly communicative.’ Then he said aloud: ‘Shall we go out on the terrace?’

As they crossed the dining-room Jules stopped Mr Dimmock and handed him a letter. ‘Just come, sir, by messenger,’ said Jules.

Nella dropped behind for a second with her father. ‘Leave me alone with this boy a little—there’s a dear parent,’ she whispered in his ear.

‘I am a mere cypher, an obedient nobody,’ Racksole replied, pinching her arm surreptitiously. ‘Treat me as such. Use me as you like. I will go and look after my hotel.’ And soon afterwards he disappeared.

Nella and Mr Dimmock sat together on the terrace, sipping iced drinks. They made a handsome couple, bowered amid plants which blossomed at the command of a Chelsea wholesale florist. People who passed by remarked privately that from the look of things there was the beginning of a romance in that conversation. Perhaps there was, but a more intimate acquaintance with the character of Nella Racksole would have been necessary in order to predict what precise form that romance would take.

Jules himself served the liquids, and at ten o’clock he brought another note. Entreating a thousand pardons, Reginald Dimmock, after he had glanced at the note, excused himself on the plea of urgent business for his Serene master, uncle of the Grand Duke of Posen. He asked if he might fetch Mr Racksole, or escort Miss Racksole to her father. But Miss Racksole said gaily that she felt no need of an escort, and should go to bed. She added that her father and herself always endeavoured to be independent of each other.

Just then Theodore Racksole had found his way once more into Mr Babylon’s private room. Before arriving there, however, he had discovered that in some mysterious manner the news of the change of proprietorship had worked its way down to the lowest strata of the hotel’s cosmos. The corridors hummed with it, and even under-servants were to be seen discussing the thing, just as though it mattered to them.

‘Have a cigar, Mr Racksole,’ said the urbane Mr Babylon, ‘and a mouthful of the oldest cognac in all Europe.’

In a few minutes these two were talking eagerly, rapidly. Felix Babylon was astonished at Racksole’s capacity for absorbing the details of hotel management. And as for Racksole he soon realized that Felix Babylon must be a prince of hotel managers. It had never occurred to Racksole before that to manage an hotel, even a large hotel, could be a specially interesting affair, or that it could make any excessive demands upon the brains of the manager; but he came to see that he had underrated the possibilities of an hotel. The business of the Grand Babylon was enormous. It took Racksole, with all his genius for organization, exactly half an hour to master the details of the hotel laundry-work. And the laundry-work was but one branch of activity amid scores, and not a very large one at that. The machinery of checking supplies, and of establishing a mean ratio between the raw stuff received in the kitchen and the number of meals served in the salle à manger and the private rooms, was very complicated and delicate. When Racksole had grasped it, he at once suggested some improvements, and this led to a long theoretical discussion, and the discussion led to digressions, and then Felix Babylon, in a moment of absent-mindedness, yawned.

Racksole looked at the gilt clock on the high mantelpiece.

‘Great Scott!’ he said. ‘It’s three o’clock. Mr Babylon, accept my apologies for having kept you up to such an absurd hour.’

‘I have not spent so pleasant an evening for many years. You have let me ride my hobby to my heart’s content. It is I who should apologize.’

Racksole rose.

‘I should like to ask you one question,’ said Babylon. ‘Have you ever had anything to do with hotels before?’

‘Never,’ said Racksole.

‘Then you have missed your vocation. You could have been the greatest of all hotel-managers. You would have been greater than me, and I am unequalled, though I keep only one hotel, and some men have half a dozen. Mr Racksole, why have you never run an hotel?’

‘Heaven knows,’ he laughed, ‘but you flatter me, Mr Babylon.’

‘I? Flatter? You do not know me. I flatter no one, except, perhaps, now and then an exceptionally distinguished guest. In which case I give suitable instructions as to the bill.’

‘Speaking of distinguished guests, I am told that a couple of German princes are coming here to-morrow.’

‘That is so.’

‘Does one do anything? Does one receive them formally—stand bowing in the entrance-hall, or anything of that sort?’

‘Not necessarily. Not unless one wishes. The modern hotel proprietor is not like an innkeeper of the Middle Ages, and even princes do not expect to see him unless something should happen to go wrong. As a matter of fact, though the Grand Duke of Posen and Prince Aribert have both honoured me by staying here before, I have never even set eyes on them. You will find all arrangements have been made.’

They talked a little longer, and then Racksole said good night.

‘Let me see you to your room. The lifts will be closed and the place will be deserted. As for myself, I sleep here,’ and Mr Babylon pointed to an inner door.

‘No, thanks,’ said Racksole; ‘let me explore my own hotel unaccompanied. I believe I can discover my room.’

When he got fairly into the passages, Racksole was not so sure that he could discover his own room. The number was 107, but he had forgotten whether it was on the first or second floor.

Travelling in a lift, one is unconscious of floors. He passed several lift-doorways, but he could see no glint of a staircase; in all self-respecting hotels staircases have gone out of fashion, and though hotel architects still continue, for old sakes’ sake, to build staircases, they are tucked away in remote corners where their presence is not likely to offend the eye of a spoiled and cosmopolitan public. The hotel seemed vast, uncanny, deserted. An electric light glowed here and there at long intervals. On the thick carpets, Racksole’s thinly-shod feet made no sound, and he wandered at ease to and fro, rather amused, rather struck by the peculiar senses of night and mystery which had suddenly come over him. He fancied he could hear a thousand snores peacefully descending from the upper realms. At length he found a staircase, a very dark and narrow one, and presently he was on the first floor. He soon discovered that the numbers of the rooms on this floor did not get beyond seventy. He encountered another staircase and ascended to the second floor. By the decoration of the walls he recognized this floor as his proper home, and as he strolled through the long corridor he whistled a low, meditative whistle of satisfaction. He thought he heard a step in the transverse corridor, and instinctively he obliterated himself in a recess which held a service-cabinet and a chair. He did hear a step. Peeping cautiously out, he perceived, what he had not perceived previously, that a piece of white ribbon had been tied round the handle of the door of one of the bedrooms. Then a man came round the corner of the transverse corridor, and Racksole drew back. It was Jules—Jules with his hands in his pockets and a slouch hat over his eyes, but in other respects attired as usual.

Racksole, at that instant, remembered with a special vividness what Felix Babylon had said to him at their first interview. He wished he had brought his revolver. He didn’t know why he should feel the desirability of a revolver in a London hotel of the most unimpeachable fair fame, but he did feel the desirability of such an instrument of attack and defence. He privately decided that if Jules went past his recess he would take him by the throat and in that attitude put a few plain questions to this highly dubious waiter. But Jules had stopped. The millionaire made another cautious observation. Jules, with infinite gentleness, was turning the handle of the door to which the white ribbon was attached. The door slowly yielded and Jules disappeared within the room. After a brief interval, the night-prowling Jules reappeared, closed the door as softly as he had opened it, removed the ribbon, returned upon his steps, and vanished down the transverse corridor.

‘This is quaint,’ said Racksole; ‘quaint to a degree!’

It occurred to him to look at the number of the room, and he stole towards it.

‘Well, I’m d—d!’ he murmured wonderingly.

The number was 111, his daughter’s room! He tried to open it, but the door was locked. Rushing to his own room, No. 107, he seized one of a pair of revolvers (the kind that are made for millionaires) and followed after Jules down the transverse corridor. At the end of this corridor was a window; the window was open; and Jules was innocently gazing out of the window. Ten silent strides, and Theodore Racksole was upon him.

‘One word, my friend,’ the millionaire began, carelessly waving the revolver in the air. Jules was indubitably startled, but by an admirable exercise of self-control he recovered possession of his faculties in a second.

‘Sir?’ said Jules.

‘I just want to be informed, what the deuce you were doing in No. 111 a moment ago.’

‘I had been requested to go there,’ was the calm response.

‘You are a liar, and not a very clever one. That is my daughter’s room. Now—out with it, before I decide whether to shoot you or throw you into the street.’

‘Excuse me, sir, No. 111 is occupied by a gentleman.’

‘I advise you that it is a serious error of judgement to contradict me, my friend. Don’t do it again. We will go to the room together, and you shall prove that the occupant is a gentleman, and not my daughter.’

‘Impossible, sir,’ said Jules.

‘Scarcely that,’ said Racksole, and he took Jules by the sleeve. The millionaire knew for a certainty that Nella occupied No. 111, for he had examined the room with her, and himself seen that her trunks and her maid and herself had arrived there in safety. ‘Now open the door,’ whispered Racksole, when they reached No.111.

‘I must knock.’

‘That is just what you mustn’t do. Open it. No doubt you have your pass-key.’

Confronted by the revolver, Jules readily obeyed, yet with a deprecatory gesture, as though he would not be responsible for this outrage against the decorum of hotel life. Racksole entered. The room was brilliantly lighted.

‘A visitor, who insists on seeing you, sir,’ said Jules, and fled.

Mr Reginald Dimmock, still in evening dress, and smoking a cigarette, rose hurriedly from a table.

‘Hello, my dear Mr Racksole, this is an unexpected—ah—pleasure.’

‘Where is my daughter? This is her room.’

‘Did I catch what you said, Mr Racksole?’

‘I venture to remark that this is Miss Racksole’s room.’

‘My good sir,’ answered Dimmock, ‘you must be mad to dream of such a thing. Only my respect for your daughter prevents me from expelling you forcibly, for such an extraordinary suggestion.’

A small spot half-way down the bridge of the millionaire’s nose turned suddenly white.

‘With your permission,’ he said in a low calm voice, ‘I will examine the dressing-room and the bath-room.’

‘Just listen to me a moment,’ Dimmock urged, in a milder tone.

‘I’ll listen to you afterwards, my young friend,’ said Racksole, and he proceeded to search the bath-room, and the dressing-room, without any result whatever. ‘Lest my attitude might be open to misconstruction, Mr Dimmock, I may as well tell you that I have the most perfect confidence in my daughter, who is as well able to take care of herself as any woman I ever met, but since you entered it there have been one or two rather mysterious occurrences in this hotel. That is all.’ Feeling a draught of air on his shoulder, Racksole turned to the window. ‘For instance,’ he added, ‘I perceive that this window is broken, badly broken, and from the outside. Now, how could that have occurred?’

‘If you will kindly hear reason, Mr Racksole,’ said Dimmock in his best diplomatic manner, ‘I will endeavour to explain things to you. I regarded your first question to me when you entered my room as being offensively put, but I now see that you had some justification.’ He smiled politely. ‘I was passing along this corridor about eleven o’clock, when I found Miss Racksole in a difficulty with the hotel servants. Miss Racksole was retiring to rest in this room when a large stone, which must have been thrown from the Embankment, broke the window, as you see. Apart from the discomfort of the broken window, she did not care to remain in the room. She argued that where one stone had come another might follow. She therefore insisted on her room being changed. The servants said that there was no other room available with a dressing-room and bath-room attached, and your daughter made a point of these matters. I at once offered to exchange apartments with her. She did me the honour to accept my offer. Our respective belongings were moved—and that is all. Miss Racksole is at this moment, I trust, asleep in No. 124.’

Theodore Racksole looked at the young man for a few seconds in silence.

There was a faint knock at the door.

‘Come in,’ said Racksole loudly.

Someone pushed open the door, but remained standing on the mat. It was Nella’s maid, in a dressing-gown.

‘Miss Racksole’s compliments, and a thousand excuses, but a book of hers was left on the mantelshelf in this room. She cannot sleep, and wishes to read.’

‘Mr Dimmock, I tender my apologies—my formal apologies,’ said Racksole, when the girl had gone away with the book. ‘Good night.’

‘Pray don’t mention it,’ said Dimmock suavely—and bowed him out.

Chapter Four. Entrance of the prince

NEVERTHELESS, sundry small things weighed on Racksole’s mind. First there was Jules’ wink. Then there was the ribbon on the door-handle and Jules’ visit to No. 111, and the broken window—broken from the outside. Racksole did not forget that the time was 3 a.m. He slept but little that night, but he was glad that he had bought the Grand Babylon Hotel. It was an acquisition which seemed to promise fun and diversion.