Полная версия

The Hype Machine

Moreover, social media manipulation does not have to change our vote choices to tip an election. Targeted efforts to increase or diminish voter turnout could be substantial enough to change overall election results, and recent evidence suggests targeted messaging can affect voter turnout. For example, a randomized experiment by Katherine Haenschen and Jay Jennings showed that targeted digital advertising significantly increased voter turnout among millennial voters in competitive districts. Research by Andrew Guess, Dominique Lockett, Benjamin Lyons, Jacob Montgomery, Brendan Nyhan, and Jason Reifler showed that randomized exposure to just a single misleading article increased belief in the article’s claims and increased self-reported intentions to vote. The meta-analysis by Green et al. estimated that direct mailings, combined with social pressure, generate an average increase in voter turnout of 2.9 percent, while canvassing generates an average increase of 2.5 percent, and volunteer phone banks generate an average increase of 2 percent. Dale and Strauss estimated the effect of text messages on voter turnout to be 4.1 percent, and there is evidence that personalized emails have a similar impact. The only studies of the impact of voter turnout as a result of social media messaging estimate that hundreds of thousands of additional votes were cast as a result of such messages.

So did Russian interference flip the 2016 U.S. presidential election or not? A full presidential term after the first Russian intervention and on the eve of the 2020 presidential election, during which Russia and others are continuing to interfere, we still don’t know. What’s scary is we can’t rule it out. It’s certainly possible given all the evidence. We don’t know because no one has studied it directly. Unfortunately, until we do democracies worldwide will remain vulnerable.

The 2020 U.S. Presidential Election

We should all have been alarmed when Special Counsel Robert Mueller testified that “the Russian government’s effort to interfere in our election is among the most serious … challenges to our democracy” he has ever seen. He stressed that the threat “deserves the attention of every American” because the Russians “are doing it as we sit here and they expect to do it during the next campaign.” He concluded that “much more needs to be done to protect against these intrusions, not just by the Russians but others.”

FBI director Christopher Wray is warning that “the threat just keeps escalating.” Not only have Russia’s attacks intensified in 2020, but other countries, like China and Iran, are “entertaining whether to take a page out of that book.” It is not clear what will happen to Americans’ trust in democracy if the 2020 election is a more convincing, more determined rerun of 2016.

What is clear is that the 2020 election is being targeted. In February, intelligence officials informed the U.S. House Intelligence Committee that Russia was intervening to support President Trump’s reelection. In March, the FBI informed Bernie Sanders that Russia was trying to tip the scales on his behalf. Intelligence officials have warned that Russia has adjusted their playbook toward newer, less easily detectable tactics to manipulate the 2020 election. Rather than impersonating Americans, they are now nudging American citizens to repeat misinformation to avoid social media platform rules against “inauthentic speech.” They have shifted their servers from Russia to the United States because American intelligence agencies are barred from domestic surveillance. They have infiltrated Iran’s cyberwar department, perhaps to launch attacks made to seem like they originated in Tehran.

In November 2019, Russian hackers successfully infiltrated the servers of the Ukrainian gas company Burisma, which was at the center of widely discredited allegations against Joe Biden and his son Hunter Biden, perhaps in an effort to dig up dirt to use during the general election. I would not be at all surprised to see a rerun of the Hillary Clinton email scandal emerge as a Joe Biden Burisma scandal in the fall of 2020. It wouldn’t be hard for foreign adversaries to seed false material into the American social media ecosystem, made to seem like real material from the successful Burisma hack, to create a scandal designed to derail the Biden campaign before anyone can debunk it. As we’ve seen, this is the signature of a fake news crisis: it spreads faster than it can be corrected, so it’s hard to clean up, even with a healthy dose of the truth.

The threat of election manipulation in 2020 is even higher due to the chaos caused by the coronavirus pandemic. With uncertainty around the viability of in-person voting, questions about voting by mail, and calls to delay the election, there can be no doubt that foreign actors will look to leverage the confusion caused by the coronavirus to disrupt our democratic process.

While some claim fake news is benign, during protests and confusion, amid the smoke, fire, and foreign interference, months from the most consequential election of our time, it is a real threat—not only to the election, but to the sanctity and peace of the election process. If the election were to be contested, fake news could escalate the contest, perhaps to violence. As Donald Horowitz has noted, “Concealed threats and outrages committed in secret figure prominently in pre-riot rumors. Since verification of such acts is difficult, they form the perfect content for such rumors, but difficulty of verification is not the only way in which they facilitate violence. … Rumors form an essential part of the riot process. They justify the violence that is about to occur. Their severity is often an indicator of the severity of the impending violence. Rumors narrow the options that seem available to those who join crowds and commit them to a line of action. They mobilize ordinary people to do what they would not ordinarily do. They shift the balance in a crowd toward those proposing the most extreme action. They project onto the future victims of violence the very impulses entertained by those who will victimize them. They confirm the strength and danger presented by the target group, thus facilitating violence born of fear.” Extreme vigilance is warranted during these difficult times when our vulnerability to manipulation is particularly high.

The threat of misinformation is not limited to Russia or American democracy. Digital interference threatens democracies worldwide. Carole Cadwalladr’s investigative reporting on the role of fake news in the Brexit vote and her work with Christopher Wiley to break the Cambridge Analytica scandal for The Guardian gave us a glimpse into the extent to which fake news has been weaponized around the world. Research by the Oxford Internet Institute found that one out of every three URLs with political hashtags being shared on Twitter ahead of the 2018 Swedish general election were from fake news sources. A study by the Federal University of Minas Gerais, the University of São Paulo, and the fact-checking platform Agência Lupa, which analyzed 100,000 political images circulating on 347 public WhatsApp chat groups ahead of the 2018 Brazilian national elections, found that 56 percent of the fifty most widely shared images on these chat groups were misleading, and only 8 percent were fully truthful. Microsoft estimated that 64 percent of Indians encountered fake news online ahead of Indian elections in 2019. In India, where 52 percent of people report getting news from WhatsApp, private messaging is a particularly insidious breeding ground for fake news, because people use private groups with end-to-end encryption, making it difficult to monitor or counteract the spread of falsity. In the Philippines, the spread of misinformation propagated to discredit Maria Ressa, the Filipino-American journalist working to expose corruption and a Time Person of the Year in 2018, was vast and swift. Similar to the Russian influence operation in Crimea, the misinformation campaign against Ressa mirrored the charges that were eventually brought against her in court. In June 2020, she was convicted of cyber libel and faced up to seven years in prison. The weaponization of misinformation and the spread of fake news are problems for democracies worldwide.

Fake News as Public Health Crisis

In March 2020, a deliberate misinformation campaign spread fear among the American public by propagating the false story that a nationwide quarantine to contain the coronavirus pandemic was imminent. The National Security Council had to publicly disavow the story. And that wasn’t the only fake news spreading about the virus. The Chinese government spread false conspiracy theories blaming the U.S. military for starting the pandemic. Several false coronavirus “cures” killed hundreds of people who drank chlorine or excessive alcohol to rid themselves of the virus. There was, of course, no cure or vaccine at the time. International groups, like the World Health Organization (WHO), fought coronavirus misinformation on the Hype Machine as part of their global pandemic response. My group at MIT supported the COVIDConnect fact-checking apparatus, the official WhatsApp coronavirus channel of the WHO, and studied the spread and impact of coronavirus misinformation worldwide. But we first glimpsed the destructive power of health misinformation on the Hype Machine the year before the coronavirus pandemic hit, during the measles resurgence of 2019.

Measles was declared eliminated in the United States in 2000. But while only 63 cases were reported in 2010, over 1,100 cases were reported in the first seven months of 2019, a nearly 1,800 percent increase. Measles is particularly dangerous for kids. It typically starts as a fever and rash, but in one in a thousand cases, it spreads to the brain, causing cranial swelling and convulsions, or encephalitis. In one in twenty kids, it causes pneumonia, preventing the lungs from extracting oxygen from the air and delivering it to the body. The disease took the lives of 110,000 kids worldwide this way in 2017.

Measles is one of the world’s most contagious viruses. You can catch it from droplets of air contaminated with an infected person’s cough hours after they’ve left the room. Nine of ten people exposed to it contract it. While the average number of people infected by one person with the coronavirus of 2020—its R0 figure—was 2.5, the R0 of measles is 15.

To prevent such a contagious disease from spreading, society has to develop herd immunity by vaccinating a large percentage of the population. With polio, which is less contagious, herd immunity can be achieved with 80 to 85 percent vaccination rates. For a highly contagious virus like measles, 95 percent of the population should be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity. Sadly, while there has been an effective vaccine since 1963, the resurgence of measles in the United States was driven by vaccine refusal, according to experts. While 91 percent of young children got the measles-mumps-rubella (or MMR) vaccine in 2017, vaccination rates in some communities fell dramatically in recent years, and it is in exactly these communities that measles skyrocketed.

This outbreak hits close to home for me because I have a six-year-old son, and the hardest-hit group, representing over half of all reported measles cases in the United States in 2019, was the Orthodox Jewish community located five blocks from our home in Brooklyn, New York. Other countrywide outbreaks have been clustered in tight-knit communities like the Jewish community in Rockland County, New York, and the Ukrainian- and Russian-American communities of Clark County, Washington, where vaccination rates hover around 70 percent, well below the threshold needed for herd immunity.

If measles is so dangerous and vaccines are so effective, why are some parents not vaccinating their kids? The answer lies partly in a wave of misinformation about the dangers of vaccination that began in 1998 with a discredited paper, published by Andrew Wakefield in the respected medical journal The Lancet, that claimed to link vaccines to autism. It was later revealed that Wakefield had been paid by lawyers suing the vaccine manufacturers, and that he was developing a competing vaccine himself. The Lancet promptly retracted the paper, and Wakefield lost his medical license. But the wave of misinformation he created continues today, aided by conspiracy theories propagated on blogs, in a widely circulated movie called Vaxxed directed by Wakefield himself, and most recently on social media.

In March 2019, addressing this wave of antivax misinformation during a public U.S. Senate hearing, Dr. Jonathan McCullers, chair of the department of pediatrics at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center and pediatrician-in-chief at Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital in Memphis, testified that, in addition to state policies on vaccine exemptions and methods of counseling, “social media and the amplification of minor theories through rapid and diffuse channels of communication, coupled with instant reinforcement in the absence of authoritative opinions, is now driving … vaccine hesitancy. When parents get much of their information from the Internet or social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook, reading these fringe ideas in the absence of accurate information can lead to understandable concern and confusion. These parents may thus be hesitant to get their children vaccinated without more information.” The anecdotal evidence that social media misinformation drives the spread of vaccine-preventable diseases like measles is troubling.

The Antivax King of Facebook

Larry Cook describes himself as a “full time [antivax] activist.” As of 2019, he was also the antivax king of Facebook. His Stop Mandatory Vaccination organization is a for-profit entity that makes money peddling antivax fake news on social media and earning referral fees from sales of antivax books on Amazon. He also raises money through GoFundMe campaigns that pay for his website, his Facebook ads, and his personal bills. Cook’s Stop Mandatory Vaccination and another organization called the World Mercury Project, headed by Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., bought 54 percent of the antivaccine ads on Facebook in 2019.

Cook’s antivax Facebook ad campaigns targeted women over twenty-five in Washington State, a population likely to have kids who need vaccines. More than 150 such posts aimed at such women, promoted by seven Facebook accounts including Cook’s, were viewed 1.6 million to 5.2 million times and garnered about 18 clicks per dollar spent on the campaigns. Facebook’s average cost per click across all industries hovers around $1.85. When you do the math, you see that Cook’s reach is insanely efficient. These data suggest he pays about six cents per click.

In early 2019, Facebook search results for information about vaccines were dominated by antivaccination propaganda. YouTube’s recommendation algorithm pushed viewers “from fact-based medical information toward anti-vaccine misinformation,” and “75% of Pinterest posts related to vaccines discussed the false link between measles vaccines and autism.” In a paper published in 2019, researchers at George Washington University found that Russian Twitter bots were posting about vaccines twenty-two times more often than the average Twitter user, linking vaccination misinformation to Russia’s efforts to hijack the Hype Machine.

Like political fake news, antivax misinformation is concentrated. Analysis by Alexis Madrigal of The Atlantic showed that the top 50 vaccine pages on Facebook accounted for nearly half of the top 10,000 vaccine-related posts and 38 percent of all the likes on these posts from January 2016 to February 2019. In fact, just seven antivax pages generated 20 percent of the top 10,000 vaccine posts during this time.

As I will describe in the next chapter, the Hype Machine’s networks are highly clustered around tight-knit communities of people with similar views and beliefs. We live in an information ecosystem that connects like-minded people. The measles outbreaks in New York and Washington in 2019 and 2020 are taking place in tight-knit communities of like-minded people. In the same way that Russian misinformation wouldn’t need to convince the majority of Americans to affect elections (small numbers in key swing states would be enough), antivax social media campaigns wouldn’t have to convince large swaths of people to forgo vaccinations to create an outbreak. To bring the levels of vaccination below the thresholds needed for herd immunity, they would only have to convince small numbers of people in tight-knit communities, who would then share the misinformation among themselves.

Research that analyzed the interactions of 2.6 million users with 300,000 vaccine-related posts over seven years found that the vaccine conversations taking place on Facebook were happening in exactly these types of tight-knit communities. The findings showed that “the consumption of content about vaccines is dominated by the echo chamber effect and that polarization increased over the years. Well separated communities emerged from the users’ consumption habits. … The majority of users consume in favor or against vaccines, not both.” These tight-knit communities in Washington State are the exact communities that Larry Cook and antivax profiteers have targeted with their Facebook ads. They are also the same communities in which disease outbreaks are occurring.

In early 2019, social media platforms took notice. Instagram began blocking antivaccine-related hashtags like #vaccinescauseautism and #vaccinesarepoison. YouTube announced it is no longer allowing users to monetize antivaccine videos with ads. Pinterest banned searches for vaccine content. Facebook stopped showing pages and groups featuring antivaccine content and tweaked its recommendation engines to stop suggesting users join these groups. They also took down the Facebook ads that Larry Cook and others had been buying. The social platforms took similar steps to stem the spread of coronavirus fake news in 2020. Will these measures help slow the coronavirus, measles outbreaks, and future pandemics? Will fake news drive the spread of preventable diseases? Answers to these questions lie in the emerging science of fake news.

The Science of Fake News

Despite the potentially catastrophic consequences of the rise of fake news for our democracies, our economies, and our public health, the science of how and why it spreads online is still in its infancy. Until 2018, most scientific studies of fake news had only analyzed small samples or case studies of the diffusion of single stories, one at a time. My colleagues Soroush Vosoughi and Deb Roy and I set out to change that when we published our decade-long study of the spread of false news online in Science in March 2018.

In that study, we collaborated directly with Twitter to study the diffusion of all the verified true and false rumors that had ever spread on the platform from its inception in 2006 to 2017. We extracted tweets about verified fake news from Twitter’s historical archive. The data included approximately 126,000 Twitter cascades of stories spread by 3 million people over 4.5 million times. We classified news as true or false using information from six independent fact-checking organizations (including Snopes, PolitiFact, FactCheck, and others) that exhibited 95 to 98 percent agreement on the veracity of the news. We then employed students working independently at MIT and Wellesley College to check for bias in how the fact-checkers had chosen those stories.

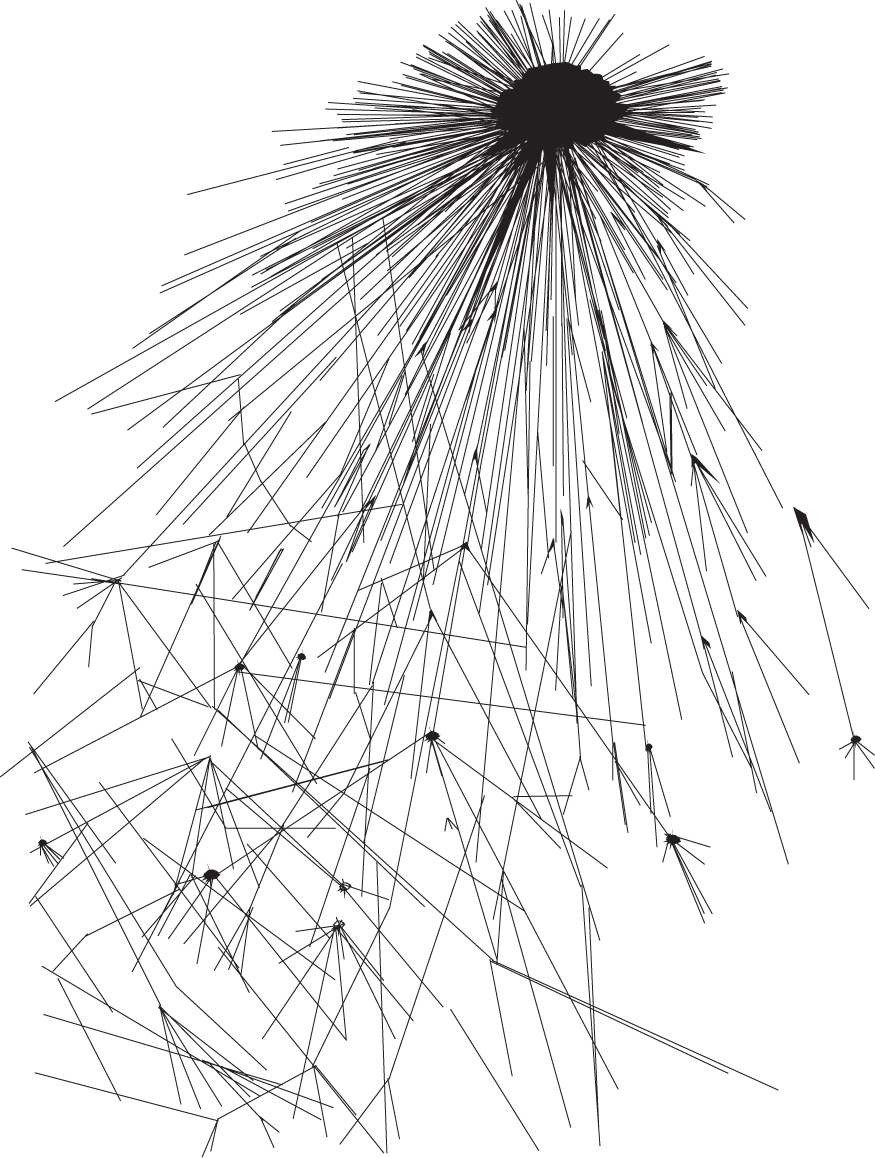

Once we had a comprehensive database of verified rumors spanning the ten years of Twitter’s existence, we searched Twitter for mentions of these stories, followed their sharing activity to the “origin” tweets (the first mention of a story on Twitter), and re-created the retweet cascades (unbroken chains of retweets with a common, singular origin) of these stories spreading online. When we visualized these cascades, the sharing activity took on bizarre, alien-looking shapes. They typically began with a starburst pattern of retweets emanating from the origin tweet and then spread out, with new retweet chains that looked like the tendrils of a jellyfish trailing away from the starburst. I’ve included an image of one of these false news cascades in Figure 2.2. These cascades can be characterized mathematically as they spread across the Twitter population over time. So we analyzed how the false ones spread differently than the true ones.

Figure 2.2 The spread of a false news story through Twitter. Longer lines represent longer retweet cascades, demonstrating the greater breadth and depth at which false news spreads.

Our findings surprised and disturbed us. In all categories of information, we discovered, false news spread significantly farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than the truth—sometimes by an order of magnitude. While the truth rarely diffused to more than 1,000 people, the top 1 percent of false news cascades routinely diffused to as many as 100,000 people. It took the truth approximately six times as long as falsehood to reach 1,500 people and twenty times as long to travel ten reshares from the origin tweet in a retweet cascade. Falsehood spread significantly more broadly and was retweeted by more unique users than the truth at every cascade depth. (Each reshare spreads the information away from the origin tweet to create a chain or cascade of reshares. The number of links in a chain is the cascade’s “depth.”)

False political news traveled deeper and more broadly, reached more people, and was more viral than any other category of false news. It reached more than 20,000 people nearly three times faster than all other types of false news reached just 10,000 people. News about politics and urban legends spread the fastest and was the most viral. Falsehoods were 70 percent more likely to be retweeted than the truth, even when controlling for the age of the account holder, activity level, and number of followers and followees of the original tweeter and whether the original tweeter was a verified user.

While one might think that characteristics of the people spreading the news would explain why falsity travels with greater velocity than the truth, the data revealed the opposite. For example, one might suspect that those who spread falsity had more followers, followed more people, tweeted more often, were more often “verified” users, or had been on Twitter longer. But the opposite was true. People who spread false news had significantly fewer followers, followed significantly fewer people, were significantly less active on Twitter, were “verified” significantly less often, and had been on Twitter for significantly less time, on average. In other words, falsehood diffused farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than the truth despite these differences, not because of them. So why and how does fake news spread?

Lies spread online through a complex interaction of coordinated bots and unwitting humans working together in an unexpected symbiosis.

Social Bots and the Spread of Fake News

Social bots (software-controlled social media profiles) are a big part of how fake news spreads. We saw this in our Twitter data when we analyzed Russia’s information operation in Crimea in 2014 and in the decade of data in our broader Twitter sample. The way social bots are used to spread lies online is both disturbing and fascinating.

In 2018 my friend and colleague Filippo Menczer at Indiana University, along with his colleagues Chengcheng Shao, Giovanni Ciam-paglia, Onur Varol, Kai-Cheng Yang, and Alessandro Flammini, published the largest-ever study on how social bots spread fake news. They analyzed 14 million tweets spreading 400,000 articles on Twitter in 2016 and 2017. Their work corroborated our finding that fake news was more viral than real news. They also found that bots played a big role in spreading content from low-credibility sources. But the way bots worked to amplify fake news was surprising, and it highlights the sophistication with which they are programmed to prey on the Hype Machine.