Полная версия

The Hype Machine

An Actress’s Rise to Fake News Infamy

Kamilla Bjorlin had been an actress her whole life. Since age seven, she had played bit parts in movies like Raising Helen, with Kate Hudson, and The Princess Diaries 2, with Anne Hathaway. She never really became a star, but narrative fiction was in her blood. So in 2011 she struck out on a different career path, forming a public relations and social media firm called Lidingo Holdings, specializing in investor relations and promotional research for public companies, including many biopharmaceutical firms. In fact, as alleged in a 2014 SEC complaint, Lidingo was a fake news factory engaged in “pump and dump” stock promotion schemes that posted fake articles to crowdsourced investor intelligence websites like Seeking Alpha, The Street, Yahoo! Finance, Forbes, and Investing.com, for the express purpose of moving stock prices.

Writers employed by Lidingo created pseudonyms, like the Swiss Trader, Amy Baldwin, and the Trading Maven; claimed to have MBAs and degrees in physics; and wrote fake stories praising the growth or stability of the companies they were paid to promote. But they never disclosed their financial relationship with their clients, which was why they ran afoul of the SEC. Between 2011 and 2014, Lidingo allegedly published over four hundred fake news articles and earned cash and equity payments of more than $1 million. As part of its crackdown on fake financial news, a separate SEC complaint against a similar firm called DreamTeam described an operation that provided “social media relations, marketing and branding services” to publicly traded companies and “leveraged its extensive online social network to maximize exposure” to fake news designed to inflate its clients’ stock prices.

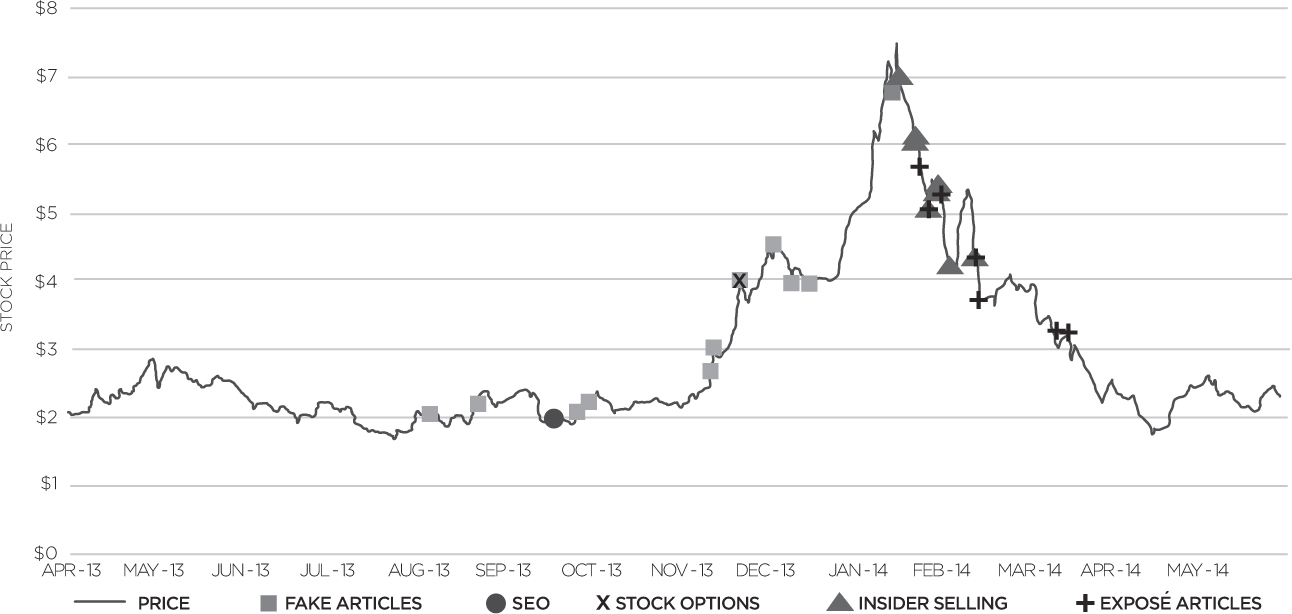

One company that Lidingo wrote fake news for was Galena Biopharma. In the summer of 2013, before Lidingo was hired, Galena’s stock price was hovering around $2 per share. Between August 2013 and February 2014, Lidingo published twelve fake news stories about Galena, claiming, for example, that the company would make “a good long-term growth investment” because it had “a promising pipeline for revenue growth” from “three strong drugs in its pipeline.”

After the first two fake news articles were published, the company issued 17.5 million new shares in a secondary equity offering (SEO) worth $32.6 million to the firm. Then five more fake news articles were published, and the stock price skyrocketed. At a November 22 board meeting, the company granted hundreds of thousands of new stock options to the CEO, COO, CMO, and each of six directors. The stock price continued to rise. In fact, it rose over 925 percent between August 2013 and January 2014 (Figure 2.1). At a January 17 board meeting, then-CEO Mark Ahn declared insiders could trade the company’s stock immediately, and starting the next day, they did, unloading $16 million worth in four weeks.

Figure 2.1 The Galena Biopharma stock price from April 2013 to May 2014, annotated with the dates when secondary equity offerings and insider selling occurred, when fake news and exposé news articles were published, and when stock options were granted.

We all know that information moves markets, but the financial impact of fake news is not immediately clear. The Galena Biopharma story directly ties the two together. But of course, Galena is a one-off. Is there any systematic, generalizable evidence of the financial impact of fake news? Luckily Galena is one of over seven thousand firms that Shimon Kogan, Tobias Moskowitz, and Marina Niessner analyzed in their large-scale study of the relationship between fake news and financial markets.

Fake News and Financial Markets

Kogan, Moskowitz, and Niessner examined data from the SEC’s undercover investigation, which identified fake news articles about public companies written to manipulate stock prices. By analyzing these validated fake news stories, Kogan, Moskowitz, and Niessner were able to systematically link the dissemination of fake news to stock price movements over time. The initial data covered a small number of articles on a small set of companies involved in the SEC investigation—171 articles on 47 companies. But the researchers broadened their sample by identifying fake news using a linguistic analysis of all the articles published on Seeking Alpha from 2005 to 2015, and on Motley Fool from 2009 to 2014. The larger sample, which looked for linguistic signatures of deceptive writing, was noisier than the verified SEC sample, but it allowed the authors to examine over 350,000 articles on over 7,500 companies over ten years. They also analyzed investors’ reactions to fake news before and after the SEC publicly announced its sting operation, which drew attention to the prevalence of fake news on these sites. The findings reveal a great deal about how fake news moves markets.

In the verified SEC data, the publication of fake news was strongly correlated with increased trading volume. Abnormal trading volume rose by 37 percent over the three days following the publication of real news articles and 50 percent more following the publication of fake news articles relative to real news articles. In other words, investors reacted to fake news even more strongly than to real news. The reactions were more pronounced for smaller firms and for firms with a greater percentage of retail (as opposed to institutional) investors. Fake articles were clicked on and read more often than real articles, and trading volume increased with the number of clicks and times an article was read.

And the effect of fake news on stock prices? Fake articles had, on average, nearly three times the impact of real news articles on the daily price volatility or absolute return of the manipulated stocks in the three days after the publication of fake news, even after controlling for recent SEC filings, firm press releases, and return volatility in the days leading up to the article.

The SEC went public with its investigation of fake news in 2014, filing lawsuits against several companies and the fake news factories they worked with, including Lidingo and DreamTeam. When the public revelation of the sting operation drew investors’ attention to the fact that fake news was being published on websites like Seeking Alpha, Kogan et al. used the public revelation of the sting to examine whether increased awareness of fake news eroded consumers’ trust in real news. Not surprisingly, fake news had a bigger impact on trading volume and price volatility before the SEC announcement than after it. But investors were also less moved by real news once the SEC drew attention to the existence of fake news, demonstrating the potential for fake news to erode the public’s trust in news altogether.

If fake news can disrupt markets, it can affect everyone in society, whether we read and share it or not. More important (as I will show when we discuss the troubling rise of “deepfakes” later in this chapter), if fake news can successfully disrupt markets, it creates a political incentive for economic terrorism. And as we saw in Crimea, the weaponization of misinformation is one of the most insidious threats to democracy in the Information Age. The most egregious example to date is Russia’s interference in American democracy in 2016.

The Political Weaponization of Misinformation

When the Mueller report was released in April 2019, pundits, politicians, and the press pored over it, looking for the juiciest bits to support their positions and to entice readers and viewers with salacious headlines. Most of them skipped over volume one and turned directly to volume two, which addressed President Trump’s alleged obstruction of the FBI’s Russia investigation. But when I read the Mueller report, I was shocked not by the juicy political potential of volume two but by the clear geopolitical reality described in volume one: Russia, an active foreign adversary, had systematically used the Hype Machine to attack American democracy and manipulate the results of the 2016 U.S. presidential election. It was one of the most comprehensive weaponizations of misinformation the world has ever seen.

Two studies commissioned by the U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee, one led by New Knowledge and the other by John Kelly, founder and CEO of Graphika, detail the extent of Russian misinformation campaigns targeting hundreds of millions of U.S. citizens in 2016. When I had lunch with John and Graphika’s chief innovation officer, Camille François, at the Union Square Café in Manhattan in early 2019, they told me the attack on our democracy was even more sophisticated than the media was giving it credit for. They were both deeply concerned about what they had uncovered. While their report is public, the look on their faces when discussing it was revealing. These two highly regarded experts were worried—and when the experts are worried, we should be too.

Russia’s attack was well planned. The Internet Research Agency created fake accounts on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, Google, Tumblr, SoundCloud, Meetup, and other social media sites months, sometimes years, in advance. They amassed a following, coordinated with other accounts, rooted themselves in real online communities, and gained the trust of their followers. Then they created fake news intended to suppress voting and to change our vote choices, in large part toward Republican candidate Donald Trump and away from Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton. The fake news included memes about Black Lives Matter, the mistreatment of American veterans, the Second Amendment and gun control, the supposed rise of sharia law in the United States, and well-known falsehoods like the accusation that Hillary Clinton was running a child sex ring out of the basement of a pizza shop in Washington, D.C. (known as “PizzaGate”). They spread these memes through organic sharing and paid promotion to boost their reach on social media.

On Twitter, they established a smaller number of source accounts, which posted fake content, and close to four thousand sharing accounts, which amplified the content through retweets and trending hashtags. The source accounts were manually controlled, while the sharing accounts were more often “cyborg” accounts that were partly automated and partly manual. Automated accounts, run by software robots, or “bots,” tweeted and retweeted with greater frequency at prespecified times. Software doesn’t get tired or need bathroom breaks, so the bot army was always on, propagating fake news and engaging the American electorate around the clock.

A lot has been written about the “Great Hack” of 2016. By now we’ve learned that Russian disinformation* was broad based and sophisticated. But did it actually change the outcome of the 2016 U.S. presidential election (or for that matter the outcome of the Brexit vote in the U.K. or of elections in Brazil, Sweden, and India)? To assess whether it flipped the U.S. election result, we have to answer two additional questions: Was the reach, scope, and targeting of Russian interference sufficient to change the result? And if so, did it successfully change people’s voting behavior enough to accomplish that goal?

The Reach, Scope, and Targeting of Russian Election Interference

During the 2016 election, Russian fake news spread to at least 126 million people on Facebook and garnered at least 76 million likes, comments, and other reactions there. It reached at least 20 million people on Instagram and was even more effective there, amassing at least 187 million likes, comments, and other reactions. Russia sent at least 10 million tweets from accounts that had more than 6 million followers on Twitter. I say “at least” because what we have uncovered so far may just be the tip of the iceberg. Analysis shows, for example, that the twenty most engaging false election stories on Facebook (whether from Russia or elsewhere) in the three months before the election were shared more and received more comments and reactions than the twenty most engaging true election stories. The Hype Machine became a clear conduit for misinformation, with one study estimating that 42 percent of visits to fake news websites (and only 10 percent of visits to top news websites) came through social media.

As astonishing as those numbers sound, the scale of fake news in 2016 was considerably smaller than that of real news. For example, in their nationally representative sample of web browsers, Andrew Guess, Brendan Nyhan, and Jason Reifler found that while 44 percent of Americans visited fake news websites in the weeks before the election, these visits comprised only 6 percent of their visits to real news websites. Similarly, David Lazer and his colleagues found that only 5 percent of registered voters’ total exposures to political URLs on Twitter during the 2016 election were from fake news sources. Hunt Allcott and Matthew Gentzkow estimated the average American saw “one or several” fake news stories in the months before the election.

If these numbers seem small, it’s worth noting some eccentricities in the way these data were collected. News is only considered “fake” in Allcott and Gentzkow’s study if it is one of 156 verified fake news stories. The other two studies analyze restrictive lists of approximately 300 fake news websites. For example, Guess et al. exclude Breitbart, InfoWars, and all of YouTube when characterizing “fake news sources.” So the 44 percent of voting-age Americans who visited at least one of their restricted list of fake news websites in the final weeks before the election does not count visitors to these popular sources of fake news. In other words, 110 million voting-age Americans visited a narrow list of fake news websites that excluded Breitbart, InfoWars, and YouTube. Our best estimates put the full number of voting-age Americans exposed to fake news during the 2016 election at between 110 million and 130 million. So whether voters’ exposure to fake news was “small-scale” is still hotly debated.

The distributions were skewed by a few viral hits, and a smaller percentage of voters saw the largest concentration of fake news. Guess et al. found that the 20 percent of Americans with the most conservative news diets were responsible for 62 percent of visits to fake news websites and that Americans over sixty were much more likely to consume fake news. On Twitter, Grinberg et al. found that 1 percent of registered voters consumed 80 percent of the fake news and that 0.1 percent accounted for 80 percent of “shares” from fake news websites. In a second, representative online survey of 3,500 Facebook users, Guess, Nyhan, and Reifler found that only 10 percent of respondents shared fake news and that they were highly concentrated among Americans over sixty-five. This level of concentration, which (as I will describe in Chapter 9) is typical of the Hype Machine, might make you skeptical of the power of fake news to influence a broad swath of society. But several caveats should accompany such skepticism.

We know that the “superspreaders” and “superconsumers” of fake news, who drive the concentration in these samples, are mostly bots. Grinberg et al. note, for example, that their median supersharer tweeted a whopping seventy-one times a day on average, with an average of 22 percent of their tweets containing fake news URLs, while their median panel member tweeted only 0.1 times a day. The researchers concluded that “many of these [superspreader and superconsumer] accounts were cyborgs.” Excluding bots, Grinberg et al. found that members of their panel averaged 204 exposures to fake news during the last thirty days of the 2016 campaign, which amounts to seven exposures a day. Assuming only 5 percent of these exposures were seen, they estimate that the average human saw one fake news story every three days leading up to the election.

While some argue fake news isn’t important because it constitutes a small part of the average citizen’s overall media diet, it’s not clear that its volume is proportional to its impact. Fake news is typically sensational and may therefore be more striking and persuasive than everyday news stories. Singular news stories, like Willie Horton, Mike Dukakis riding a tank, and Howard Dean’s guttural scream are widely regarded as tipping points in their respective elections. Whether fake news stories behave similarly is an empirical question that remains unanswered. Furthermore, fake news doesn’t live just on social media. It is frequently picked up and repeated by broadcast media and public figures, creating a feedback loop that amplifies its reach beyond social media alone.

The 2000 U.S. presidential election was decided by 537 votes in one key swing state—Florida. Russia’s 2016 misinformation campaign targeted voters in swing states like Florida, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Michigan. My colleagues at the Oxford Internet Institute analyzed over 22 million tweets containing political hashtags shared in the week before the election. They geolocated a third of these tweets, tying sharers and recipients to the states in which they resided. When they analyzed the geographic distribution of Russian misinformation around the country, they found that “the proportion of misinformation was twice that of the content from experts and the candidates themselves.” When they calculated whether a state had more or less Russian fake news, they found that 12 of 16 swing states were above the average. They concluded that Russian fake news was “surprisingly concentrated in swing states, even considering the amount of political conversation occurring in the state.” Although more than 135 million votes were cast in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, six swing states (New Hampshire, Minnesota, Michigan, Florida, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania) were decided by margins of less than 2 percent, and 77,744 votes in three swing states (Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania) effectively decided the election.

On Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, Russian fake news targeted persuadable voters in swing states with content that was tailored to their interests using “@” mentions and hashtags to draw users to memes custom-designed for them. For example, two days before the election, supporters of the Black Lives Matter movement were drawn to voter suppression memes that encouraged them not to vote. The account @woke_blacks posted a meme to its Instagram account that read, “The excuse that a lost Black vote for Hillary is a Trump win is bs. Should you decide to sit-out the election, well done for the boycott,” while @afrokingdom_ posted that “Black people are smart enough to understand that Hillary doesn’t deserve our votes! DON’T VOTE!” New Knowledge estimated that 96 percent of the Instagram content linked to the Internet Research Agency focused on Black Lives Matter and police brutality, spreading “overt suppression narratives.”

We know that President Trump’s former campaign manager, Paul Manafort, shared polling data with the Russian political consultant Konstantin Kilimnik and that targeting persuadable voters in swing states (which is possible with such polling data) was standard operating procedure for Cambridge Analytica, the self-described “election consultancy” that used 87 million Americans’ stolen data to build predictive models of voters’ susceptibility to persuasion, and the topics and content most likely to persuade them. (I will evaluate Cambridge Analytica’s “psychographic profiling” in Chapter 9.)

If misinformation targeted a small but potentially meaningful number of persuadable voters in key swing states, was the right misinformation targeted at the right voters? Skeptics contend that such misinformation preached to the choir, because exposure was “selective”—meaning that die-hard conservatives saw pro-Trump fake news, while die-hard liberals saw pro-Clinton fake news, making it unlikely that it changed anyone’s mind. Guess et al. found 40 percent of Trump supporters and only 15 percent of Clinton supporters read pro-Trump fake news, while 11 percent of Clinton supporters and only 3 percent of Trump supporters read pro-Clinton fake news. Sixty-six percent of the most conservative voters, the farthest-right decile, visited at least one pro-Trump fake news site and read an average of 33.16 pro-Trump fake news articles.

But the argument that fake news was preaching to the choir doesn’t address voter turnout, because ideologically consistent fake news can motivate voters to turn out even if it doesn’t change their vote choices. Furthermore, while voters on the extreme right were disproportionately more likely to consume pro-Trump fake news (thus “preaching to the choir”), moderate Clinton supporters and undecideds in the middle of the political spectrum were significantly more likely to consume pro-Trump fake news than pro-Clinton fake news. Could their exposure to fake news have persuaded them to vote for Trump or to abstain? That depends on how social media manipulation affects voting.

Social Media Manipulation and Voting

Was the reach, scope, and targeting of the Russian interference sufficient to change the election result? We can’t rule it out. Although exposure to fake news was much less than exposure to real news and was concentrated among a select set of voters, it likely reached between 110 million and 130 million people. It didn’t need to affect everyone to tip the election—just a few hundred thousand persuadable voters in key swing states. Which was exactly who Russia targeted. The next big question: did it have an effect on voting? To answer that, we need to understand the science of voter turnout and vote choice.

Sadly, as I write this, only two published studies link social media exposure to voting. The first, a 61-million-person experiment conducted by Facebook during the 2010 U.S. congressional elections, found social media messages encouraging voting caused hundreds of thousands of additional verified votes to be cast. The second, a follow-up experiment by Facebook during the 2012 presidential election, replicated the findings of the first, although the “get out the vote” messages were slightly less effective, as is typical in higher-stakes presidential elections. (I will analyze both of these studies in detail in Chapter 7.) But the main takeaway, for the purposes of our discussion of the 2016 election, is that social media messaging can significantly increase voter turnout, with minimal effort. While there are only two large-scale studies of the effect of social media on voting, the substantial research on the effects of persuasive messaging on voter turnout and vote choice can help us to calibrate the likely effects of Russian interference on the 2016 election.*

With regard to vote choice, some meta-analytic reviews suggest the effects of impersonal contact (mailings, TV, and digital advertising) on vote choice in general elections are very small. Kalla and Broockman conclude, from a meta-analysis of forty-nine field experiments, that “the best estimate of the size of persuasive effects [i.e., effects of advertising on vote choice] in general elections … is zero.” But their data do not consider social media. And there is substantial uncertainty in their estimates, such as the effect of impersonal contact within two months of Election Day, which was when Russia’s attack was in full swing.

They also found significant effects of persuasive messages on vote choice in primaries, on issue-specific ballot measures, and on campaign targeting of persuadable voters. Rogers and Nickerson found, for example, that informing voters in favor of abortion rights that a candidate did not support such rights had a 3.9 percent effect on reported vote choice, suggesting the possibility that targeted, issue-specific manipulation of the type Russia deployed could have changed vote choices. The power of persuasive messaging on issue-specific ballot measures also highlights the possibility of interference being directed at large numbers of regional elections and local policy measures, which could collectively shift the political direction of a country without having to impact results at a national level. This threat is particularly insidious, because it would be much harder to detect than interference in a general election.