Полная версия

Polarity Analysis in Homeopathy:

1. Does the befallment increase, lessen or pass away:

By movement of the part in question? By walking in a room or in the fresh air? By standing, sitting, or lying?

2. Does the symptom alter itself:

By eating? By drinking? Under some other condition? By speaking, coughing, sneezing, or during another bodily function?

3. What time of the day or night is the symptom especially wont to come?

In this way, what is peculiar and characteristic about each symptom becomes evident.”

NOTE

WHEN CHOOSING A REMEDY, IT IS ESPECIALLY IMPORTANT TO CHECK THAT THE PATIENT’s MODALITIES MATCH THOSE OF THE REMEDY.

NOTE

BY MENTAL SYMPTOMS WE MEAN THE ALTERATIONS IN THE PATIENT’S STATE OF MIND AS A RESULT OF ILLNESS, NOT THE CHARACTER OR STATE OF MIND OF THE PREVIOUSLY HEALTHY PERSON.

Hahnemann is here describing the modalities, which are obviously also valid for patient symptoms, and says that through them “ … what is peculiar and characteristic about each symptom becomes evident”. This means that, above all, the modalities of the patient must match those of the chosen remedy. § 153 is frequently interpreted differently, however, to mean that above all unusual, striking, rare, and even peculiar symptoms should determine the choice of remedy – the socalled keynotes or “as if” symptoms. This type of symptom generally has very few remedies assigned in the repertory. If only such symptoms are taken into account, the result can be that the peculiar symptom matches the remedy but the patient’s modalities do not. In such a constellation, healing is only rarely possible because the characteristic aspects of the remaining symptomatology are ignored.

NOTE

AFTER A DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF THE LIKELY REMEDIES HAS BEEN PRODUCED, BASED ON THE MODALITIES AND OTHER IMPORTANT SYMPTOMS, THE CURRENT MENTAL SYMPTOMS CAN TIP THE SCALES FOR THE FINAL CHOICE OF REMEDY.

In § 211, Hahnemann writes: “The patient’s emotional state often tips the scales in the selection of the homeopathic remedy.” Here too we are concerned with alterations due to illness, not with the character or state of mind of the previously healthy person. That the patient’s emotional state often “tips the scales” means that first – with the help of the modalities and other important symptoms – a differential diagnosis of the likely remedies is produced. When choosing one of these likely remedies, the patient’s emotional state can then be the decisive factor.

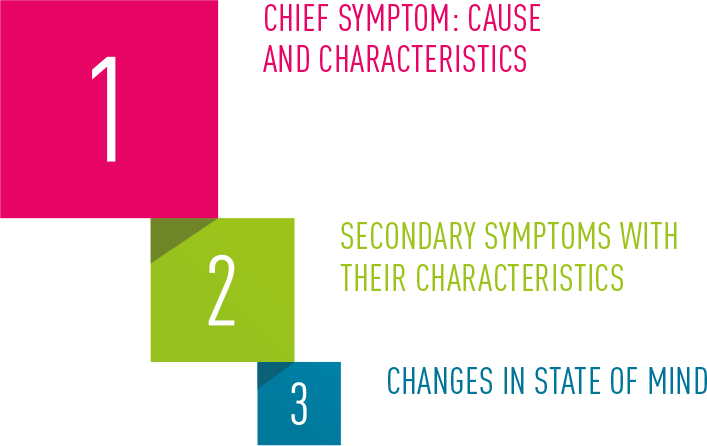

1.2.3 HIERARCHY OF SYMPTOMS

After comprehensive casetaking as described in § 84 to § 95, we generally end up with a wealth of symptoms, each of which has a different influence on the choice of remedy. In the introduction to the revised edition (2000) of Boenninghausen’s PB7, K-H. Gypser has outlined the symptom weighting that can be found in different places in Boenninghausen’s writings. First comes the causative factor of the current illness, if one can be found (but this is not to be confused with the conventional medical notion of causation). Second is the chief symptom with its characteristics (modalities, sensations and clinical findings, location, concomitants and extent). Third are the secondary symptoms. Fourth are the changes in the state of mind (table 1). A hierarchy is of particular importance if the symptoms from different levels in the hierarchy contradict one another. For example, if the chief symptom (the abdominal complaint that has caused the patient to seek out the doctor) is characterized by amelioration from warmth, yet a secondary symptom like a skin eruption is characterized by aggravation from warmth, we must give preference to the modality of the chief symptom – the conflicting secondary symptom must be disregarded in such a case. If we are unsure which is the chief symptom and which is the secondary symptom, we must exclude contradictory modalities from the repertorisation. If the chief symptom has only a few or even no modalities, we might decide to use the distinct modalities of the secondary symptoms for the repertorisation: this often occurs in skin disease.

Table 1: Boenninghausen’s Hierarchy of Symptoms

1.2.4 RELIABILITY OF SYMPTOMS

The quality of symptoms plays a decisive role in the reliability with which the remedy is chosen. Due to our prior experience gained in the treatment of ADHD, an investigation was conducted during the preparation of the Swiss double-blind study into ADHD with the aim of identifying unreliable symptoms. This involved analyzing the choice of symptoms from the cases in which initially an ineffective remedy was chosen, followed later by the correct remedy. In this way it was possible to identify the symptoms that often led to incorrect prescriptions. The evaluation of 100 cases produced 77 unreliable symptoms, including 44 mind symptoms, 9 weather modalities and 6 food symptoms (desire / dislike / aggravation). These symptoms were subsequently excluded from the repertorisation.

Due to the frequency of these excluded symptoms, many cases were now characterized by a lack of symptoms, which therefore impeded the process of choosing the remedy. A possible substitute for the unreliable symptoms was the modalities of the disturbances in perception found in ADHD patients. These had not been used so far because — as pathognomonic symptoms — the consensus within homeopathy was that they should not be included in the repertorisation. Yet the use of this type of symptom immediately led to a marked improvement in the results.

NOTE

PATHOGNOMONIC SYMPTOMS CAN BELONG TO THE SET OF CHARACTERISTIC SYMPTOMS. IF SO, THEY MUST NOT BE EXCLUDED FROM THE REPERTORISATION.

The term pathognomonic was first introduced to homeopathy by G.H.G. Jahr. Later C. Dunham explained in his work the importance assigned to these symptoms by homeopathic physicians of the nineteenth century: pathognomonic at that time meant irreversible changes in organs (for example, liver cirrhosis or a scar), which should therefore be excluded from the repertorisation because they usually cannot be healed.11,12,13 But the current understanding of pathognomonic is different: it now refers to those “hallmark” symptoms used to establish a conventional medical diagnosis. For example, the pathognomonic symptoms of acute lymphoblastic leukemia are: pallor, petechiae, fatigue, bone pain, enlarged liver and spleen, and so on. Such symptoms belong to the set of characteristic symptoms, so that it is a misapplication of the law of similars to exclude them from the repertorisation. The false interpretation of the ambiguous term “pathognomonic symptom” has therefore had disastrous effects on the precision of homeopathic prescribing.

NOTE

WHEN CHOOSING A REMEDY, IT IS BEST TO INCLUDE MIND SYMPTOMS ONLY DURING THE MATERIA MEDICA COMPARISON.

Yet why can mental symptoms be so misleading? “Mind” is the smallest chapter in the PB. Boenninghausen justified this by saying that mind symptoms are often consequences and therefore do not constitute reliable symptoms, and he pointed out that mental symptoms are often overlooked or incorrectly ascertained. He therefore recommended looking up the state of mind, with all its subtlety, in the original sources, and restricted himself in the area of mind to the essentials. Boenninghausen placed great emphasis on including the state of mind only when making the final choice from the list of likely remedies – at the stage of differentiating the remedies, and he explicitly restricted himself to the CHANGE in the state of mind during an illness (see § 210 ff, especially the footnote to § 210). “One often finds that people who were patient in healthy times become, in disease: stubborn, violent, hasty, and even insufferable, self-willed and in due succession, impatient and despairing. Those who were formerly chaste and modest often become lascivious and shameless.”

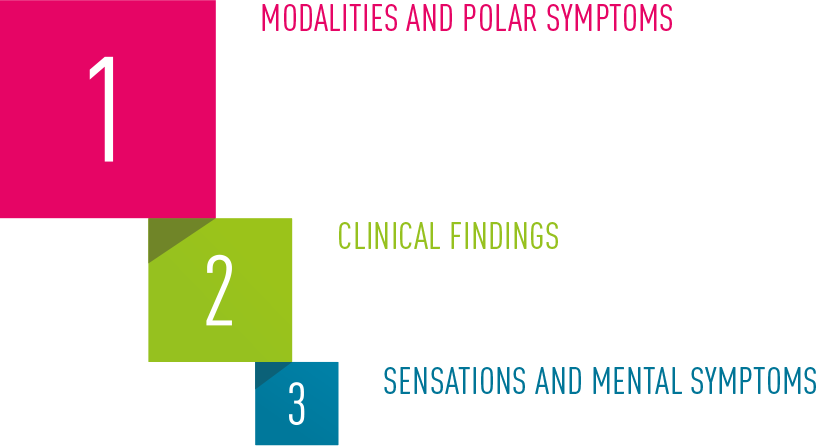

In contrast to the mind symptoms, modalities are generally unambiguous. Regardless of individual, cultural, or linguistic background, the sense of warmth or cold (for example) is everywhere perceived the same. Other polar symptoms such as thirst and thirstlessness also permit little scope for misinterpretation. Based on the ADHD study, it has been possible to draw up a hierarchy of the reliability of symptoms (table 2, symptom reliability, decreasing from top to bottom).

Table 2: Hierarchy of Symptom Reliability

1.2.5 HERING’S LAW

That which Constantine Hering described in 1865 in an article in the Hahnemannian Monthly with the title “Hahnemann’s Three Rules Concerning the Rank of Symptoms” is now known simply as Hering’s Law.14 This is the essence of it:

NOTE

THE CHARACTERISTIC SYMPTOMS THAT, IN THE COURSE OF THE ILLNESS, WERE THE LAST TO APPEAR TAKE PRIORITY WHEN DETERMINING THE REMEDY.

“Suppose a patient had experienced the symptoms he suffers in the order a, b, c, d, e, then they ought to leave him, if the cure is to be perfect and permanent, in the order e, d, c, b, a. The latest symptoms have thus the highest rank in deciding the choice of remedy.”

From this he drew the conclusion that the most recent symptoms of the patient should take priority when determining the remedy, since these should be the first to disappear.

Hering’s Law is important because it often enables us to solve cases with a multitude of symptoms where it is difficult to obtain a good overview – by directing us to concentrate on only the most recent characteristic symptoms when choosing the remedy. With a remedy chosen in this way, old symptoms usually improve too. As soon as multiple complaints exist together, it is important to know when each one began.

1.3 QUIZ 1: FUNDAMENTALS OF HOMEOPATHY

1 What does Hahnemann mean by that which is to be healed (§ 7)?

2 Define the symptom complex (§ 6).

3 Which of the patient’s symptoms must particularly match the symptoms of the remedy (§ 133)?

4 Define mind symptoms.

5 What is the role played by mind symptoms in the choice of remedy (§ 211)?

6 What role is played by the character traits and characteristics of the patient when choosing the remedy?

> you can find the answers on p. 283.

1.4 DEVELOPMENT OF POLARITY ANALYSIS

1.4.1 BOENNINGHAUSEN’S CONTRAINDICATIONS

NOTE

THE GENIUS OF A REMEDY INCLUDES THE MODALITIES, SENSATIONS, AND CLINICAL FINDINGS THAT HAVE REPEATEDLY APPEARED IN THE PROVINGS AT VARIOUS DIFFERENT LOCATIONS, AND WHICH CAN GENERALLY BE HEALED. THESE ARE IN FACT THE ACTUAL CHARACTERISTICS OF A REMEDY.

The polarities are first mentioned in the preface to the revised edition of Boenninghausen’s Pocket Book by Klaus-Henning Gypser.7 When choosing a remedy, Boenninghausen strived to match the patient’s set of symptoms and especially the modalities (that is, the circumstances that aggravate or ameliorate the symptoms) as closely as possible to the genius of the remedy.

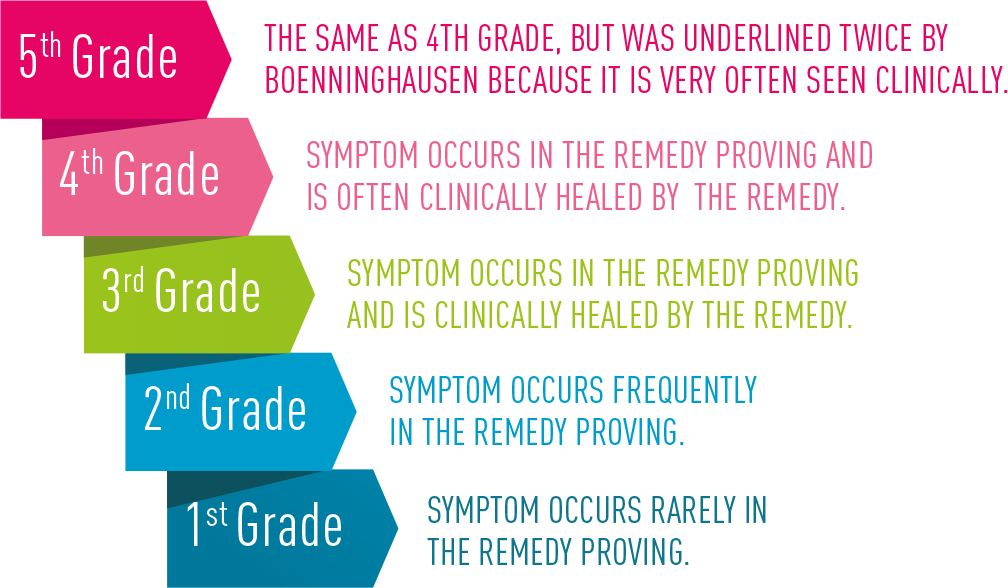

Table 3: Boenninghausen’s Grading of Symptoms

Symptoms of the 3rd to 5th grades are genius symptoms since they are observed in different localizations in proving and clinical practice.

NOTE

POLAR SYMPTOMS ARE THOSE SYMPTOMS THAT CAN HAVE AN OPPOSITE ASPECT, AN “OPPOSITE POLE” SUCH AS THIRST /THIRSTLESSNESS, COLD AGGRAVATES / COLD AMELIORATES OR DESIRE FOR FRESH AIR / DISLIKE OF FRESH AIR.

In order to confirm the remedy choice, he advised checking whether one or more aspects of the patient’s symptom set contradict the genius symptoms of the remedy. This contradiction can concern polar symptoms (see note on the left).

NOTE

POLAR SYMPTOMS OF THE REMEDY IN QUESTION SHOULD BE MATCHED AT AS HIGH A GRADE AS POSSIBLE (3-5). IF THE OPPOSITE POLE IS LISTED FOR THE REMEDY AT A HIGH GRADE (3-5) BUT THE PATIENT SYMPTOM AT A LOW GRADE (1-2), THE GENIUS OF THE REMEDY DOES NOT MATCH THE PATIENT’S SYMPTOM SET. THE REMEDY IS THEREFORE CONTRAINDICATED

With many remedies, both poles of a polar symptom are covered, but in different grades. Boenninghausen said that a contradiction occurs when the patient symptom is observed in the 1st or 2nd grade with the opposite pole listed for the remedy in the 3rd, 4th, or 5th grade. In this case, the opposite pole (not the patient symptom) corresponds to the genius of the remedy. Boenninghausen found that such constellations hardly ever lead to healing, and indeed they are a contraindication for the remedy concerned. When checking unsuccessful prescriptions, made without regard to Boenninghausen’s rule, we frequently find contraindications that have been missed.

1.4.2 POLARITY DIFFERENCE

In 2001, during the initial phase of the ADHD double-blind study, Boenninghausen’s notion of contraindications was used as the foundation of polarity analysis, a mathematical procedure that leads to higher hit rates*, resulting in more solid clinical improvements than was so far seen with conventional homeopathic methods. By grading the polar symptoms of the shortlisted remedies, polarity analysis calculates the likelihood of healing, the polarity difference.

This is calculated for each remedy by adding the grades of the patient’s polar symptoms. From the resulting value, the grades of the corresponding opposite polar symptoms are subtracted. The higher the polarity difference calculated in this way, the more the remedy corresponds to the patient’s characteristic symptoms, assuming there are no contraindications. The rigorous application of these insights about the polarity of symptoms leads to a quantum leap in the precision with which we can determine the correct remedy.4,5 The effects on the accuracy of the prescriptions and the quality of improvement has been evaluated in several prospective outcome studies (chapter 6). The following example demonstrates the procedure.

1.4.2.1 CASE 1 MR B.Z. 50 YEARS OLD SUBACUTE GRANULOMATOUS THYROIDITIS DE QUERVAIN

CASETAKING: Mr Z*. has always been healthy. He comes to see us due to a decline in his sporting performance. His current illness began six weeks ago with transitory pain in the right side of the neck, lasting a few days. Since then he has suffered from palpitations and outbreaks of sweating as well as an intractable, dry cough. He was forced to drop out of the Bern Grand Prix, a city run, which greatly upset him.

CLINICAL FINDINGS: General condition reduced, BMI 22.3 kg/m2 (rather thin), dark rings round the eyes. Blood pressure 130/80, pulse 72/min. Neck and throat normal, early mesosytolic click on cardiac auscultation, lung examination negative, abdominal wall soft, no hepatosplenomegaly, flow murmur in right lower abdomen. Peripheral pulse normal, cursory neurological status normal.

With the help of the Checklist for Acute Illness: Airways (see chapter 7.2) we identified the following symptoms:

• Warmth: worse p**

• Desire for open air p

• Heat with inclination to uncover p

• Quick pulse p

• Pressure external: worse p

• Tenderness to pressure of neck, right p

The repertorisation can proceed if the case has a minimum of five polar symptoms, since these together with the modalities constitute the distinctive and characteristic quality of the complaints, and are at the same time the most reliable symptoms for determining the remedy (see table 2). In this case we used the English version of the software Boenninghausen’s PB, edition 2000.8

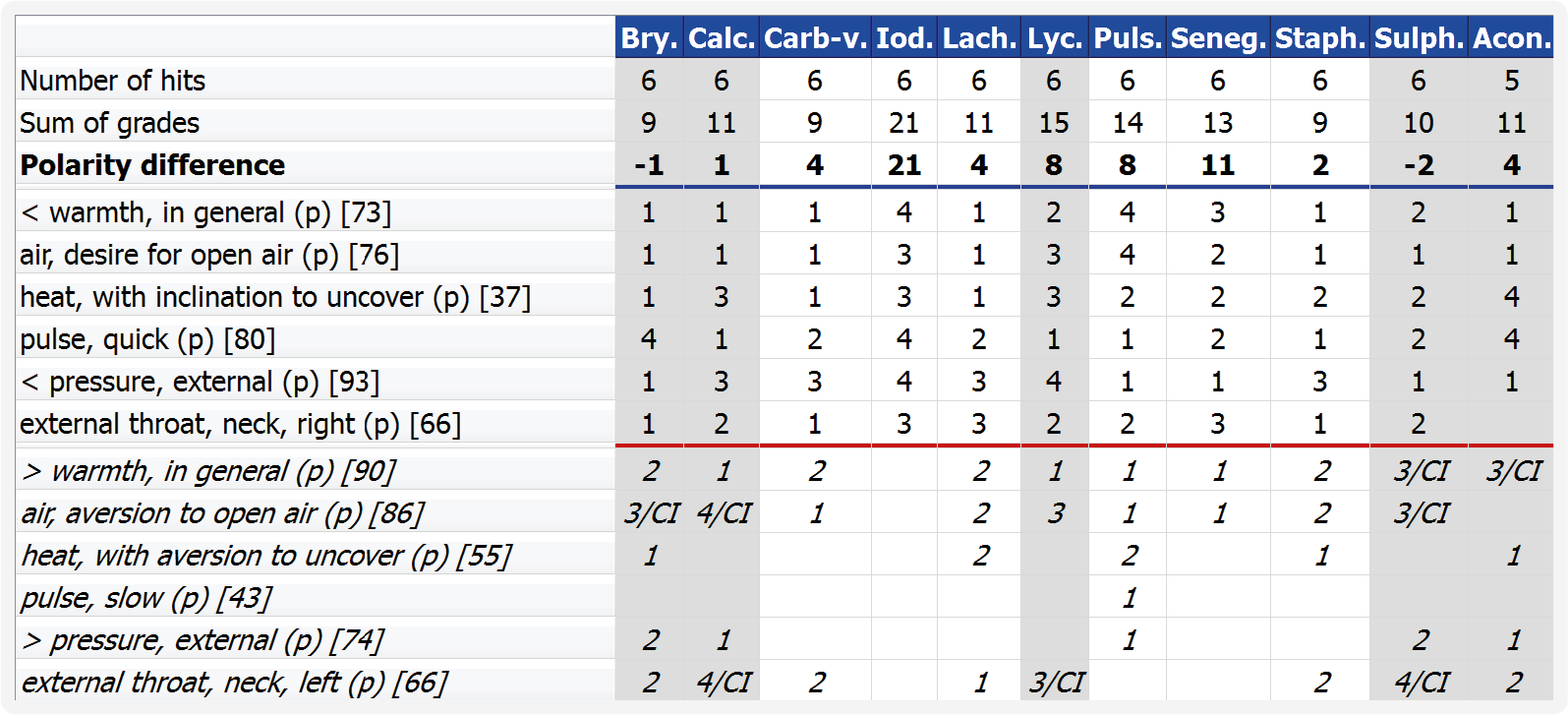

Table 4: Repertorisation Demonstration Case 1, Patient B. Z.

EXPLANATION OF TABLE 4

1. The remedies are ordered according to the number of hits.

Further remedies are not shown for reasons of space, and because they have a smaller number of hits and a lower polarity difference.

2. Symptom descriptions:

< = worse ; > = better

Polar symptoms are marked with (p).

The number after the symptom in square brackets (for example, < warmth in general [73]) refers to the number of remedies matching the symptom. This information is important because it shows how strongly the choice of remedy is restricted by the use of the symptom rubric.

3. Patient symptoms:

These are listed underneath the blue line and above the red line.

4. Opposite poles:

These are shown in italics and are found below the red line.

5. Calculation of the polarity difference: The grades of the polar patient symptoms of a remedy are added up. From this total, the sum of the grades of the opposite poles listed for the remedy are subtracted: the result is the polarity difference (example: Iodum 21-0=21 or Lycopodium 15-7=8).

6. Contraindications, ci: The opposite poles at the genius level (grades 3-5) are compared with the grades of the patient’s symptoms. If the patient’s symptom has a low grade (1-2) but the opposite pole is listed for the remedy with a high grade (3-5), the genius of this remedy does not correspond to the characteristics of the patient’s symptom; the remedy is therefore contraindicated.

Example: When checking Bryonia, we find that the patient’s symptom desire for open air is listed at the 1st grade whereas the opposite pole aversion to open air is listed for the remedy at the 3rd grade. In other words, dislike of fresh air is a genius symptom of Bryonia. Therefore Bryonia does not fit the patient’s symptoms and is contraindicated.

7. Columns with contraindications (ci) and relative contraindications (ci) are shaded grey so that we can instantly see which remedies are contraindicated. (The relative contraindications are explained in the key to table 13, see p. 50).

INTERPRETATION OF THE REPERTORISATION

NOTE

THE HIGHER THE POLARITY DIFFERENCE, THE MORE LIKELY IT IS THAT THE REMEDY CORRESPONDS TO THE PATIENT’S CHARACTERISTIC SYMPTOMS, ASSUMING THERE ARE NO CONTRAINDICATIONS.

All six symptoms are covered by ten remedies, four of which have contraindications (Bry, Calc, Lyc, and Sulph – all shaded grey); these remedies are therefore discarded. Iodum has an outstanding polarity difference (PD) of 21, followed by Senega as the second possible remedy (PD 11). The other four remedies have, due to the much lower polarity difference, a significantly lower chance of healing the patient. The fact that Iodum stood out so strongly raised the suspicion that there was pathology of the thyroid gland. So the TSH (Thyroid Stimulating Hormone) level was determined, and was found to be massively lower than normal at 0.01 mU/l (normal: between 0.27 – 4.50), indicating a case of hyperthyroidism.

Iodine crystals

PRESCRIPTION AND PROGRESS

The patient was given a dose of Iodum 200C and referred to the endocrinologist. There was an instant improvement in the patient’s condition following the Iodum, and the cough disappeared. The general state and the ability to exercise returned to normal. Ten days later, the endocrinologist performed a sonographic examination and found a small adenoma of 7mm diameter in the lower right lobe of the thyroid. The metabolism typical of hyperthroidism had already returned to normal (TSH now 0.29 mU/l), and the free thyroxine (fT4) was slightly diminished at 8.1 pmol/l (normal: 9.1 - 23.8). He diagnosed subacute granulomatous thyroiditis de Quervain. The slightly depressed thyroid function persisted, so the patient has since been taking a low dose of thyroxine as a substitution therapy.

REMARKS

This case is interesting from the homeopathic point of view because it demonstrates how polarity analysis can make good use of simple polar symptoms to precisely capture the illness and even help us to identify the malfunctioning organ. If the patient had come for homeopathic treatment sooner, the substitution therapy would probably not have become necessary. In contrast to the contraindications, in which only symptoms with high-grade opposite poles are used, the polarity difference makes use of all the polar symptoms. It thereby establishes as accurately as possible which remedy is the most similar to the patient’s symptom set. This eliminates differences in the grading of the major and minor remedies. The major remedies, the polychrests, are well-known and have very many symptoms, which is why the grading of these remedies’ symptoms is generally higher than those of the symptoms of the less-well-known minor remedies. The calculation of the polarity difference based on the difference in grading between the patient symptom and the opposite pole, largely compensates this disadvantage of the minor remedies. The result is that polarity analysis often indicates surprisingly minor remedies as the best choice, leading to good healing results.

1.5 CASETAKING AND CHOICE OF REMEDY

The usual casetaking is shorter for acute illness, comprehensive for chronic illness, and even more comprehensive for multimorbid patients (those with three or more illnesses). This is followed by an examination of the patient. If necessary, additional diagnostic procedures are initiated, such as the TSH assay for the patient discussed above in 1.4.2.1. It is fundamentally a good idea, before every homeopathic treatment, to make a precise conventional medical diagnosis, to avoid being surprised halfway through treatment by a complaint that was not included in the initial assessment of the case. (If the homeopath is not a physician, the patient’s physician should order all the appropriate tests and make the diagnosis before homeopathic treatment starts.) Only when the diagnosis has been clarified and it is clear that homeopathy is a suitable treatment for the patient can the actual treatment begin. In the next step the casetaking is supplemented with modalities and polar symptoms, elicited as comprehensively as possible. For acute illness we provide checklists; for chronic illness there are questionnaires available.

1.5.1 CHECKLISTS AND QUESTIONNAIRES

The checklists for acute illness consist of two parts: first there is space for the patients to freely describe their chief symptoms; then there is a list of polar modalities and symptoms, which the patients underline if they match their current illness.