Полная версия

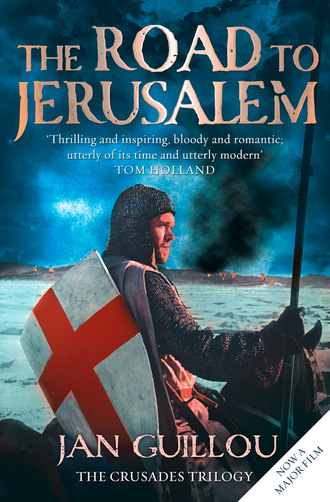

The Road to Jerusalem

‘I want to have time to confess,’ she whispered.

Father Henri chased out the thrall women, pulled on his prayer vestments, and blessed her. Then he was ready to hear her confession.

‘Father forgive me, for I have sinned,’ she gasped with fear shining in her eyes. She had to take a few deep breaths and collect herself before continuing.

‘I’ve had ungodly thoughts, worldly thoughts. I gave Varnhem to you and yours not only because the Holy Spirit told me that it was a right and just cause. I also hoped that with this gift I would be able to appease the Mother of God because in foolishness and selfishness I had asked her to spare me from more childbeds, even though I know it’s our duty to populate the earth.’

She had been talking low and fast, waiting for the next jab of pain, which struck just as she finished speaking. Her face contorted and she bit her lip to keep from screaming.

Father Henri got up and fetched a linen cloth, dipping it in cold water in a pail by the door. He went to her, raised her head, and began bathing her face and brow.

‘It is true, my child,’ he whispered, leaning forward to her cheek and feeling her fiery fear, ‘that God’s grace cannot be bought for money, that it’s a great sin both to sell and buy what only God can bestow. It’s also true that you in your mortal weakness have felt fear and have asked the Mother of God for aid and consolation. But that is no sin. And as far as the gift of Varnhem is concerned, it was prompted by the Holy Spirit descending upon you and giving you a vision which you were ready to accept. Nothing in your will can be stronger than His will, which you have obeyed. I forgive you in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. You are now without sin and I will leave you so, for I must go and pray.’

He carefully laid her head back down and could see that somewhere deep inside her pain she seemed relieved. Then he left quickly and brusquely ordered the women back into the house; they rushed in like a flock of black birds.

But Sot stayed where she was and tugged cautiously on his robe, saying something that he didn’t understand at first, since neither of them was fluent in the common Swedish speech. She renewed her effort, speaking very slowly, and supplementing her words with gestures. It then dawned on him that she had a secret potion made of forbidden herbs that could alleviate pain; the thralls used to give it to their own who were about to be whipped, maimed, or gelded.

He looked down at the diminutive woman’s dark face as he pondered. He knew quite well that she was baptized, so he must talk to her as if she were one of his flock. He also knew that what she told him might be true: Lucien de Clairvaux, who took care of all the garden cultivation, had many recipes that could achieve the same effect. But there was a risk that the potion the thrall women spoke of had been created using sorcery and evil powers.

‘Listen to me, woman,’ he said slowly and as clearly as he could. ‘I’m going to ask a man who knows. If I come back, then give drink. No come back, no give drink. Swear before God to obey me!’

Sot swore obediently before her new God, and Father Henri hurried off to converse with Brother Lucien first, before he gathered all the brothers to pray for their benefactress.

A short time later he spoke to Brother Lucien, who vehemently rejected the idea in fright. Such potions were very strong; they could be used for those who were wounded, dying, or for medicinal purposes when an arm or foot had to be amputated. But on pain of death one must not give such a potion to a woman giving birth, for then one would be giving it to the child as well, who might be born forever lame or confused. As soon as the child was born, of course, it would be permitted. Although by that time it was usually no longer necessary. But it could be interesting to hear what that pain-killing potion was composed of; perhaps one might gain some new ideas.

Father Henri nodded shamefully. He should have known all this, even though he specialized in writing, theology, and music, not medicine or horticulture. He hurriedly gathered the brothers to begin a very long hour of prayer.

For the time being, Sot had decided to obey the monk, even though she thought it was a shame not to lighten her mistress’s suffering. She now took charge of the other women in the room, and they pulled Sigrid out of bed, let down her hair so it flowed free: long, shiny, and almost as black as Sot’s own hair. They washed her as she shivered with cold, and then pulled a new linen shift over her head and made her walk about the room, to hasten the birth.

Through a fog of fear, Sigrid staggered around the floor between two of her thrall women. She felt ashamed, like a cow being led about at market. She heard the bell chime from the longhouse but was unsure if it was only her imagination.

The next wave of pain hit; it started deeper inside her body, and she could feel that it would last longer this time. Then she screamed, more from terror than pain, and sank down on the bed. One of the thrall women held Sigrid under the arms from behind and lifted her body upwards, while they all shrieked at once that she had to help, she had to push. But she didn’t dare push. She must have fainted.

When the twilight turned to night and the thrushes fell silent, a stillness seemed to come over Sigrid. The pains that had come so often in the last few hours seemed to have stopped.

Sot and all the others knew this was an ominous sign. Something had to be done. Sot took one of the others with her and they padded out into the night, sneaking past the longhouse where the murmuring and singing of the monks could be heard faintly through the thick walls, and on to the barn. They brought out a young ram with a leather rope around its neck and led it away in the falling darkness toward the forbidden grove. There they bound the rope around one rear hoof and slung the other end over one of the huge oak branches in the grove. As Sot pulled on the rope so that the ram hung with one hind leg in the air, the other thrall woman fell upon the animal. She grabbed it around the shoulders, and forced the animal toward the ground with all her weight, as she drew out a knife and slit its throat. They both hoisted up the struggling, screeching ram, as blood sprayed in all directions. After they tied the rope to a root of the tree, they stripped off their shifts and stood naked beneath the shower of blood and smeared it into their hair, over their breasts, and between their legs as they prayed to Frey.

When the morning dawned, Sigrid awoke from her torpor with the fires of hell burning in her anew, and she prayed desperately to the dear blessed Virgin Mary to save her from the pain, to take her now, if that was how it was to end, but at least to spare her from the pain.

The thrall women, who had been dozing around her, came quickly to life and started running their hands over her body and speaking rapidly to one another in their own unintelligible tongue. Then they began to laugh, smiling and nodding eagerly to her and to Sot, whose hair was so soaked that it hung straight down, dripping cold water as she bent over Sigrid, telling her that now was the time, now her son would soon come, but for the last time she must try to help. And the women took her under the arms and raised her halfway up in a sitting position, and Sigrid screamed wild prayers until she realized she might wake her little Eskil and frighten him. So she bit her wounded lip again and it began to bleed anew, and her mouth was filled with the taste of blood. But softly, in the midst of all that was unbearable, she found more and more hope, as if the Mother of God were now actually standing at her side, speaking gently to her and encouraging her to do as her clever and loyal thralls instructed. And Sigrid bore down and bit her lip again to keep from screaming. Now the monks’ voices could be heard out in the dawn, very loud, like a praise-song or a psalm meant to drown out the terror.

Suddenly it was over. She saw through her sweat and tears a bloody bundle down below. The women in the room bustled about with water and linen cloths. She sensed them washing and chattering, she heard some slaps and a cry, a tiny, tremulous, bright sound that could only be one thing.

‘It’s a fine healthy boy,’ said Sot, beaming with joy. ‘Mistress has borne a well-formed boy with all the fingers and toes he should have. And he was born with a caul!’

They lay him, washed and swaddled, next to her aching, distended breasts, and she gazed into his tiny wrinkled face and was amazed he was so small. She touched him gently and he got an arm free and waved it in the air until she stuck out a finger, which he instantly grabbed and held tight.

‘What will the boy be named?’ asked Sot with a flushed, excited face.

‘He shall be called Arn, after Arnäs,’ whispered Sigrid, exhausted. ‘Arnäs and not Varnhem will be his home, but he will be baptized here by Father Henri when the time comes.’

TWO

King Sverker’s son Johan died as he deserved. King Sverker had of course followed the advice he had been given by Father Henri, to see to it that the Danish jarl took his wife back to Halland at once. But both King Sven Grate and his jarl scornfully rejected the subsequent part of Father Henri’s plan, to arrange a marriage between the royal but roguish son and the other violated Danish woman, so that war could thus be avoided with a blood bond.

The fault lay perhaps not so much in Father Henri’s plan as in the fact that King Sven Grate wanted war. The more proposals for mediation came from King Sverker, the more King Sven Grate wanted war. He thought, possibly correctly, that the king of the Goths was exhibiting weakness when he offered first one thing and then another to avoid going into battle.

As a last resort, King Sverker had prevailed upon the Pope’s Cardinal Nicolaus Breakspear to pay a visit to Sven Grate on his way to Rome and speak of reason and peace.

The cardinal failed at this task, just as he had recently failed to ordain an archbishop over a unified Götaland and Svealand.

The papal commission to name an archbishop had failed because the Swedes and Goths were unable to agree on the location of the archbishop’s cathedral, and thus where the archbishop should have his see. The cardinal’s peace-making assignment failed for the simple reason that the Danish king was convinced of his coming victory. His newly conquered realms would then be subject to Archbishop Eskil in Lund, so Sven Grate could see no Christian reason for refraining from war.

King Sverker had made no preparations for the defense of the realm, since he was too wrapped up in mourning his queen, Ulvhild, and preparing for a wedding with yet another twice-widowed woman, Rikissa. Perhaps he also thought that all the intercessions he had secured for himself at the cloister would save both him and the country.

His oafish son Johan harboured no such belief in salvation by intercession. And if the Danes should emerge from the coming battle victorious, for his part all hope would be lost. So he, and not his father the king, called a ting at the royal manor in Vreta to decide how to plan the defense against the Danes.

He had no idea how hated he was as an outcast. If his father had not been both old and weak of flesh, he would have condemned his son to death for committing two heinous deeds as well as perjury. Everyone understood that except possibly Johan himself. No man of honor wanted to prolong the war and risk losing his life for the sake of an outcast – the worst sort of violator of women.

On the other hand, many men came to the ting at Vreta filled with anticipation, but for entirely different reasons than those Johan imagined.

They had come to kill him. And they did. His own retainers didn’t lift a finger to protect him. Johan’s corpse was chopped into pieces of the proper size and flung to the swine in the back yards of Skara so that no royal funeral could take place.

In the year of Grace 1154 winter came early, and when the ice had settled in, King Sven Grate led his army up from Skåne and into the Finn Woods in Småland. The army burned and pillaged wherever they went, of course, but the advance was slowed by all the snow that year. Horses and oxen had a hard time making headway.

In addition, the peasants in Värend took defensive measures. They had decided at their ting that if they had to die, it was better to die like men in accordance with their forefathers’ ancient beliefs. Dying like a servant or thrall without offering resistance was to die in vain. Besides, nothing was certain when it came to war except for one thing: He who did not fight, or who stood alone against a foreign army, would surely die if the army passed his way. Everything else was in the hands of the gods.

And King Sven Grate truly had a difficult time of it. The residents of Värend defended themselves one stretch of land at a time, from behind log jams, which they dragged onto the forest roads. It took a great deal of force and time to deal with these barricades, and victory was elusive. If the momentum seemed in their favor in the evening when the battle had to be broken off for supper, prayer, and sleep, by morning the defenders of the barricade would be gone. By then they would have regrouped in a village a bit farther on, with new people who had their own homes to defend, and then it would start all over again.

At night the soldiers in the Danish army deserted in large groups and began walking home. Those who were professional fighters knew that too much of the winter had already passed. Even though they might finally manage to get through these damned peasant defenders, they would end up mired in the spring mud on the plains of Western Götaland. Besides, the peasants of Värend had a nasty way of defending themselves. At night they would sneak up in small groups, overtake the guards, and then stab as many horses and oxen in the belly as they could before reinforcements arrived. Then they would flee into the dark forest.

A horse that has been stabbed in the belly dies quite rapidly. Oxen are a bit more resilient, but even oxen die if a pitchfork or lance point has penetrated their underbelly. Naturally, the Danish army ended up with plenty of beef to roast, but it was cold comfort, since they were forced to consume their only hope of victory.

When at last Sven Grate had to accept the fact that the war could not be won, at least not this year, he decided that the army should be divided for the retreat. He would proceed home through Skåne to the islands of Denmark. His jarl would take the other half of the remaining army home with him to Halland and his own manor. Sven Grate also had messengers sent home to announce that when they returned, the war would be over.

But in Värend there was plenty to avenge. And the story was long told of the woman Blenda, who sent out messages to the other women, and together they met the jarl and his men near the Nissa River with bread and salt pork. Quite a lot of salt pork, as it turned out. They provided an extraordinary feast, and oddly enough, there was plenty of ale to go with the salt pork.

The jarl and his men finally staggered off to a barn to sleep while the soldiers, just as drunk as the noblemen, had to make do as best they could underneath ox and sheep hides out in the snow. It was then that Blenda and the other women made their preparations. They tarred big torches and summoned their men, who were hiding in the forest.

When silence had fallen over the army’s encampment and only snoring could be heard, they carefully barred the door of the barn and then set fire to all four corners simultaneously. Then they attacked the sleeping soldiers.

The next morning, with joyous laughter, they drowned the last of the captives beneath the ice on the Nissa River, where they had chopped two big holes so that they could drag the prisoners down under the ice as if on a long fishing line.

King Sverker had won the war with the Danes without lifting a finger or sending out a single man.

No doubt he believed that this was due both to his prayers of intercession and to God’s Providence. Yet he was man enough to have Blenda and her kinsmen brought before him. And he proclaimed that the women of Värend, who had shown themselves so manly in the defense of the country, should henceforth inherit just as men did. And as an eternal emblem of war they would wear a red sash with an embroidered cross of gold, an insignia that would be granted to them alone.

If King Sverker had lived longer, his decrees would surely have had greater legal effect than they did. But King Sverker’s days were numbered. He would soon be murdered.

No fortress can be built to be impregnable. If strong enough motivation exists, any man’s home can be pillaged and burned. But the question then is whether it was worth the price. How many besiegers had been shot to death with arrows, how many had been crushed by stones, how many had lost their will and health during the siege?

Herr Magnus knew all this, and he was greatly troubled as the construction progressed. Because what he couldn’t know, what no one at that time could know, was what would happen after the death of old King Sverker. And that time was fast approaching.

Anything was possible. Sverker’s eldest son Karl might win the king’s power, and then nothing in particular would change. If nothing else, Sigrid had seen to improving her husband’s relationship to King Sverker by donating Varnhem almost as if in his name.

But it was difficult to know much about what was happening up in Svealand, and which of the Swedes was now preparing for the battle to become king. Perhaps it was some Western Goth? Perhaps someone in their own lineage or in a friendly clan or in a hostile clan. As they waited for the decision to be made, there was nothing to do but keep building.

Arnäs was located at the tip of a peninsula that jutted out into Lake Vänern, and so had a natural water defense on three sides. Next to the old longhouse a stone tower was now being erected that was as tall as seven men. The walls around the tower were still not finished, but the area was mainly protected by palisades of tightly packed, pointed oak logs. Here there was still plenty to do.

Magnus stood for a long time up in the tower on his property, trying out shots with a longbow, aiming at a bale of hay on the other side of the two wall moats. It was truly remarkable how far an arrow from a longbow could reach if he fired down from an elevated position. And after very little practice he was learning to calculate the angle so that he hit the target almost perfectly, at most an arm’s length to one side or the other. Even in its present unfinished state, Arnäs would be difficult to take, at least for a group of soldiers returning from some war or other who might need provisions on the way home. And eventually it would become even more fortified, although everything had its season, and Sigrid mostly wanted something different from Magnus.

He was well aware that she often got her way when they disagreed. By now he was even aware of how she behaved to make it look as if she weren’t actually driving him before her, but rather was obediently following the will of her husband and lord—as she had done with the matter of the high seat of his Norwegian forefathers.

In the old longhouse the high seat and the walls around the end of the hall had been decorated with oak carvings from Norway, in which the dragon ship plowed through the sea, and a great serpent whose name he had forgotten encircled the entire scene. The runic inscription was ancient and difficult to decipher.

Sigrid had first proposed that they burn all these old ungodly images now that they were building afresh. The walls should be covered instead with the tapestries of the new era, in which Christian men defended the Holy City of Jerusalem, where churches were erected and heathens baptized.

Magnus had had a hard time agreeing to the idea of burning all his forefathers’ skilfully made carvings. Such things were no longer created nowadays; in any case their like could not be found anywhere in Western Götaland. But he’d also had difficulty arguing with her words about ungodliness and heathen art. In that sense she was right. And yet the forefathers who had carved those writhing dragons and runes had known no other way of carving; now the lovely work of their hands was all that remained of them.

At the same time as they were quarrelling about the dragon patterns and the runes, they were also addressing the question of who knew how to build walls. Should the stonemasons’ talents be used first for the outer defenses, or should they build the gable of the new longhouse first?

In the old longhouse, the fireplace had stretched the whole length of the building, down the middle of the floor, so that the heat was distributed more or less evenly. In the far end of the longhouse were kept the thralls and the animals, while the master of the estate and his people and their guests lived in the part where the high seat was placed. During hard winters, heat was best conserved in this manner.

But now Sigrid had come up with new ideas, which of course she had learned from the monks down in Varnhem. Magnus still remembered his amazement and his skepticism when she drew it all in the sand before him. Everything was new, nothing was as before.

Her longhouse was divided into two halves, with a big door in the middle that led into an anteroom, and from there you entered either the master’s half or the half with the thralls and animals. In addition, the half with the thralls and animals was divided into two floors. The upper floor served as a barn for fodder, and the lower floor as stall for the livestock. In this half of the house there was no fireplace; on the contrary, fire was something that would be forbidden on pain of severe punishment.

In the other half of the longhouse, which would be their own, with a high seat as before, the far gable would be built entirely of stone. In front of it large, flat slabs would be mortared to a fireplace almost as wide as the house, and above the fireplace a huge chimney to conduct the smoke would be built into the stone.

He’d offered many objections, and she had answers to all of them. The lack of fire along the floor was not a problem; the stone walls at the end would hold the heat inside the building, keeping it warm even through the night. No, the old vents were not necessary, as the smoke would go straight up the stone chimney above the hearth. And there was no need to worry about winds blowing through the stacked logs, as the cracks would be sealed with flax and tar.

As to his concern that the thralls and animals would have no fire in their part of the house, she patiently explained that by dividing their living quarters into two floors, the heat from the animals would remain downstairs, while upstairs the thralls (and the men) could make comfortable beds of hay.

But then, in response to one of his questions, Sigrid happened to invoke the Norwegian stave churches, which certainly had no lack of dragon patterns, and she seemed to reconsider. On closer reflection she thought she could yield on the matter of the ancestral high seats and their less than Christian ornamentation. And then, quite exhilarated and relieved, Magnus agreed at once that first they had to finish the masonry work on the new longhouse. Since now he had indeed achieved what he wanted.

Of course he had seen through her, and he understood how she managed to push through her will on almost every matter. Sometimes he felt a brief wave of anger flow through his limbs and head at the thought that his wife was acting as though she and not he was the master of Arnäs.

But now, as he unstrung his longbow and shouted at one of the thralls down in the moat to gather up the arrows and return them to their place in the armoury, what he saw was not merely a beautiful sight. It was a very convincing sight.

Below him in the stronghold area, the new longhouse stood with its tarred walls gleaming and its turf roof a luxuriant green. They had converted all the thatched roofs on the buildings to turf roofs with grass, even though reeds could be easily harvested nearby. This was not only for the sake of warmth, but also because a single flaming arrow could transform thatched roofs into huge torches.