Полная версия

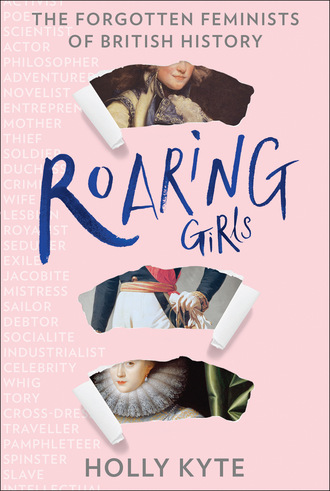

Roaring Girls

It’s quite possible Margaret was secretly relieved when these remedies didn’t work, for her own attitude to motherhood was ambivalent – society said it was her wifely duty to provide children and she felt that pressure, but the burning desire for them herself simply wasn’t there. She could barely even understand it in other women. Dynastic motives made no sense for a woman, she would later argue, since ‘neither name nor estate goes to her family’ when she marries; and then, of course, she ‘hazards her life by bringing them into the world, and hath the greatest share of trouble in bringing them up’.[19] Maternal instinct or affection didn’t even enter the equation. Margaret would soon find other ways of perpetuating herself and her name that appealed far more …

The couple thrived regardless. Conscious of her good luck in finding a husband who didn’t suppress her ideas or curb her ambitions, Margaret was respectful and adoring of William – the model of a loyal, deferential, dutiful wife. In this, at least, she was happy to play the conventional woman. In no other part of her life would she be so conformist.

TRAITORS TO THE STATE

Despite their happiness together, the Cavendishes would be dogged in the first three years of their marriage by horrors both personal and national. By the summer of 1647, Margaret’s sister Mary had died of consumption, and her beloved mother soon after, and by the end of 1648, the numerous Royalist uprisings of that year had all been crushed. The King had been imprisoned at Hurst Castle in Hampshire and his supporters purged from Parliament, and Margaret’s brother Sir Charles Lucas, leader of the Essex rebellion, had been summarily executed by firing squad, without trial.[20]

The young woman who had anxiously checked her sleeping siblings for signs of life had now lost three members of her family in less than two years – one of them ‘inhumanly murdered’[21] – and the following year her eldest brother Thomas would die, too. This torrent of grief left Margaret plagued by fears of ‘death’s dungeon’. With no faith whatsoever in an after-life, she would later write of life’s cruel brevity, likening it to ‘a flash of lightning that continues not and for the most part leaves black oblivion behind it’.[22] To many, this was heretical talk; to Margaret it was a perfectly rational hypothesis that only magnified her already nagging desire for immortality.

Unsurprisingly, during these years Margaret was diagnosed with ‘melancholy’ – a condition believed to be caused by an excess of black bile but what in reality must have been the cumulative effect of intense grief, financial worries and the stress of the ongoing political turmoil. With her budding interest in science, Margaret habitually self-medicated, purging herself with ‘vomits’ (emetics) and bleeds to rid her body of the ‘humours’ that she – and her physician – believed were making her ill.[23]

All the while the Civil War was building to its nightmarish crescendo. While Prince Charles had retreated to The Hague, where his sister Mary, wife of William II of Orange, could offer him refuge, the Cavendishes had settled in the affordable town of Antwerp in September 1648, where William maintained his tactic of blinding his creditors with extravagance by leasing the grand Rubens House from the famous painter’s widow. Here, he, Margaret and his brother Sir Charles would resume their favourite pastimes of engaging in philosophical discussion, tinkering with telescopes and conducting scientific experiments in the family laboratory. And here, they would learn the shocking news of their King’s fate.

On 30 January 1649, Charles I was executed for High Treason on a specially built scaffold outside London’s Whitehall Palace for waging war against his own Parliament. In that moment, England forcibly rid itself of a monarchy that had survived for nearly a thousand years by pedalling a symbolic (if not literal) image of safety, order and stability, presided over by an untouchable, divinely appointed sovereign. Now the King was dead, that image was irreparably scarred, the body politic had no head and only the unknown remained.

For the Royalists, this cataclysmic event meant quickly regrouping, focusing their attention on their theoretical new sovereign, Charles II, and, despite further defeated rebellions in 1650 and 1651, never quite giving up on plans to restore him. For the Cavendishes, it meant accepting a life of indefinite exile in Antwerp. William learned that he had been banished from England on pain of death, putting his assets further out of reach than ever, and in early 1651, starvation once again became a genuine threat. ‘I know not how to put bread in my mouth,’ he fretted to a friend,[24] his panic rising – largely because his brother, whose financial contributions had kept this small family of exiles just about afloat, had now had his estates sequestered, too. The only way Sir Charles could regain them was to return to England and petition for them, which carried the risk of imprisonment or being forced to take the oath of loyalty to the new Commonwealth, which had replaced the monarchy. Reluctantly, Charles was persuaded to go, and as William’s own estates were due to be sold off by Parliament and his wife was legally entitled to petition for one-fifth of their worth, it was decided that Margaret should accompany him. They set sail in November 1651, and on 10 December, with her brother John’s help, Margaret nervously put her case before the Committee for Compounding at Goldsmiths’ Hall in London. She wasn’t quite prepared, however, for the callousness of their response. They refused her appeal outright, said they would sell off the entirety of William’s estates, giving her no share of their worth whatsoever. William, they argued, was of the King’s inner circle and therefore ‘the greatest traitor to the State’, which excluded him – and his wife, who had knowingly married him after his political exile – from their clemency.

Appalled to the point of speechlessness, Margaret’s timidity silenced her when she longed to speak: ‘I whisperingly spoke to my brother to conduct me out of the ungentlemanly place, so without speaking to them one word good or bad, I returned to my lodgings.’ Utterly disheartened and ‘unpractised in public employments’, she didn’t attempt to petition the Committee again.[25] As a relatively non-offending Royalist, Sir Charles would eventually have more luck, but for now his petition dragged on interminably.

Margaret was miserable: she missed William, worried about him, and was in no mood, and no position, to enjoy herself. London was a changed place since the war – it had now entered an age of aggressively enforced austerity: seasonal festivities were banned, the theatres closed, the royal pageantry gone. High-profile Royalists were wise to keep their heads down, so Margaret did just that, retreating to her rooms, and finding solace – therapy, even – just as she had as a child: in writing. Only now it took on a new significance. She kept it secret even from her husband at this early stage, but Margaret Cavendish no longer wished to write just for her own amusement. Never again did she intend to be silenced by powerful men or her own timidity. She had decided to become a published author.

LET WRITING BOOKS ALONE

It’s hard to overstate how daring it was for Margaret Cavendish to even contemplate publishing her writing in mid-seventeenth-century England. Gagged by their poor education and mandatory silence, very few women had ever done so before 1640, and the handful who had were conscious of having overstepped their bounds into dangerously wanton territory and so tended to stick to ‘chaste’ and therefore ‘suitable’ feminine subjects: religious meditations and divine visions, poetry on love, friendship or God, domestic advice, recipes or cures. In the five years between 1616 and 1620, just eight new titles were published by women – 0.5 per cent of the 2,240 total.

But with the destabilising force of the Civil War came an undermining of all forms of established authority, and after 1640, during the war and Interregnum in particular, a mini-revolution took hold as women seized the opportunity created by the upheaval to publish books in increasing numbers. Between 1646 and 1650, new titles by women shot up to 69. And during the 1650s, almost five times as many books by women were printed than in the 1630s.[26] Aided by a brief lapse in the censorship laws,[27] this productivity boom hit both male and female writers, but women were the biggest gainers.

The rules of the game were slowly changing, but for women publishing remained a risky business. Even those who stuck to ‘feminine’ topics could still be attacked for disseminating their ideas. When Eleanor Davies published her prophetical visions in 1625, her husband was so enraged that he burnt her manuscript. And Elizabeth Avery, whose Scripture-prophecies Opened appeared in 1647, was publicly attacked for it by her own brother, who wrote in 1650, ‘your printing of a book, beyond the custom of your sex, doth rankly smell’.[28] Lady Mary Wroth, meanwhile, encountered such vitriolic accusations of betraying her sex on the publication of her romance Urania in 1621 (notably from Sir Edward Denny, who in an acrid satirical verse labelled her a ‘Hermaphrodite in show, in deed a monster’) that she was forced to deny she had ever intended to publish it at all and attempted to withdraw all copies.[29] These ancestral trolls, who abused or ridiculed any woman who dared to speak out, intimidated their quarry, certainly, but didn’t always succeed in silencing them. Women writers set about exploiting every loophole they could think of: some pre-empted attack with apologetic prefaces, others specifically addressed women or continued to confine themselves to modest, virtuous, ‘feminine’ subjects, while many chose to write anonymously or under a pseudonym.

When Margaret Cavendish strode into this daunting arena in 1653, however, with her first book, Poems and Fancies, she would take very few of these mitigating measures. Not only would she publish, she would do so under her own name and cover subjects that were considered exclusively male. This was a book whose dainty title belied its extraordinary contents. In lieu of the formal education she couldn’t have, Margaret had spent her married life absorbing like a sponge every topic under discussion in her scholarly household – philosophy, science, literature, politics – and it had all filtered into her work. Her poems were not about love or friendship or God: they described fairies that lived at the centre of the Earth; a microscopic world contained in an earring; the terror of hunted animals; the futility of war; the elements; the universe; light, sound, matter and motion; and, most extraordinary of all, the scientific theory of atomism – a school of thought, derived from the Ancient Greek philosophers Democritus, Epicurus and Lucretius, which argued that particles of different sizes, shapes and properties comprised and governed the world. Her fancies were no less surprising: she wrote allegorical dialogues between Wit and Beauty, Earth and Darkness, Melancholy and Mirth; moral discourses on pride, humility, wealth and poverty; and fantastical prose that imagined a Royalist parliament as a diseased human body in need of a cure. It was a wildly abundant compendium of every style and subject that critiqued human nature and expounded dangerously materialist and atheistic views. Coming from a woman, this was not normal.[30]

Such an ambitious work would inevitably provoke outrage and ridicule, so Margaret also included copious prefaces, epistles and addresses in her book, designed to defend her decision to publish – the only placatory tactic she would employ. In her poem ‘The Poetresses Hasty Resolution’, she describes how her initial qualms almost prevented her from publishing at all. Reason urged her to ‘do the world a good turn, / And all you write cast in the fire and burn’,[31] but ambition made her impulsive. With a gambler’s recklessness she ‘resolved to set it at all hazards’, for she had little to lose and immortality to win: ‘If fortune be my friend, then fame will be my gain, which may build me a pyramid, a praise to my memory.’[32]

She expected censure, particularly from men, who would doubtless ‘cast a smile of scorne upon my book, because they think thereby, women encroach too much upon their prerogatives; for they hold books as their crown … by which they rule’.[33] The most obvious accusations, however – that she ought to be looking after her children and household instead of indulging her whims in writing – she could easily bat away, for she had no children and her husband’s estate had been confiscated. As for any claims that she was just another aristocratic dilettante doodling away in her idle hours, Margaret would show just how seriously she took her work: she was as fond of her book, she wrote, ‘as if it were my child’, and, like a proud mother, was ‘striving to show her to the world, in hopes some may like her’. The analogy was clever; it implied not only that her mind had achieved a lasting act of creation that her body could not, but that, far from being ‘wanton’ or ‘rude’, it was in fact ‘harmless, modest and honest’ for a woman to publish her work – as natural and virtuous as being a mother.[34]

Margaret faced one challenge even greater than public disapproval, though. She was a factory of complex, unusual ideas, yet her rudimentary home-tuition had left her without the tools to perfectly express them. In this she was nothing unusual; the state of women’s education in the seventeenth century was even poorer than it had been in the last, especially for upper-class women.[35] King James I had disapproved of intellectual women and encouraged a culture of ridiculing them at court, and the attitude had stuck. Those upstart women who did acquire learning were viewed with suspicion, as the scholar Bathsua Makin knew well: ‘A learned woman is thought to be a comet,’ she wrote in An Essay to Revive the Antient Education of Gentlewomen (1673), ‘that bodes mischief, whenever it appears.’ The scholar Dr George Hickes noted the trend in 1684: ‘It is shameful, but ordinary,’ he said, ‘to see gentlewomen, who have both wit and politeness, not able yet to pronounce well what they read … They are still more grossly deficient in orthography, or in spelling right, and in the manner of forming or connecting letters.’[36] Margaret was a prime example. Her handwriting was near-illegible, her spelling wayward, her rhymes and metre flawed, her grammar idiosyncratic and her punctuation conspicuous by its absence. She was acutely aware of it – her ‘brain being quicker in creating than the hand in writing’[37] – but was often too caught up in a frenzy of creativity to be much of an editor. Her secretaries and typesetters had to pick up this slack, resulting in skewed interpretations of her meaning and rounds of later corrections.

Bowing to common opinion, Margaret concluded that it was simply ‘against nature for a woman to spell right’,[38] arguing that originality and wit were more valuable than the technicalities of form. Yes, her writing could be indulgent and baggy, her arguments incomplete and foggy, but to her a free and artless style was best: ‘Give me a style that nature frames, not art, / For art doth seem to take the pedant’s part.’[39] It’s a convenient argument when the art is largely missing, but it ignores the real problem: her lack of education. It’s been suggested that she might even have been dyslexic.[40] But having internalised the prevailing assumption that women were undeserving of education, blaming her own natural incompetence was the only defence she had.

For those looking for a straightforward feminist heroine in Margaret Cavendish, this is a problem. Keen to present herself as a wonder of the age, as something ‘other’ than the average woman, she voices the troubling suggestion that women are not naturally suited for intellectual pursuits more than once in Poems and Fancies: ‘True it is,’ she writes in one epistle, ‘spinning with the fingers is more proper to our sex, than studying or writing poetry.’[41] And in her address ‘To all writing ladies’, despite urging them to push beyond their domestic sphere into the world of politics, religion, philosophy and poetry, she adds that ‘though we be inferior to men, let us shew our selves a degree above beasts’.[42]

At this early stage in her career, when her ideas are in their infancy, Margaret is infuriatingly inconsistent on women’s intellectual worth. With her own busy, capacious, ambitious mind fighting the remnants of patriarchal indoctrination, she flip-flops from apologist to agitator and back again. Elsewhere in the same book, she delivers a defiant ‘up yours’ to the snide world outside that’s just itching to condemn her:

Tis true, the world may wonder at my confidence, how I dare put out a book, especially in these censorious times; but why should I be ashamed, or afraid, where no evil is, and not please my self in the satisfaction of innocent desires? For a smile of neglect cannot dishearten me, no more can a frown of dislike affright me … my mind’s too big, and I had rather venture an indiscretion, than lose the hopes of a fame. [43]

This is the Margaret Cavendish that feminists adore, emerging from her chrysalis: singular, ambitious, confident of her intelligence and proudly dismissive of what others think. Over time, her ideas on women, like her ideas on natural philosophy, would develop into a much more coherent, formidable statement, but for now, she was primarily on the defensive, knowing damn well that her actions, though harmless, would be seen as provocative. With Sir Edward Denny’s famous hectoring verse to Lady Mary Wroth still ringing in Margaret’s ears three decades after it was written, she imagined men telling her, too, to go back to her sewing:

Work Lady, work, let writing books alone,

For surely wiser women nere wrote one. [44]

But Margaret would do no such thing, ‘For all I desire, is Fame.’ And fame she would get. Throughout her writing career, she would produce a staggering 23 books – accounting for over half of the total number of books (just 42) published by women between 1600 and 1640.[45] With her unabashed ambitions, and with few to rival her intrepid subject matter or prolific output,[46] Margaret would stand almost entirely alone in the century as a woman writer who could not be ignored.

MANY SOBERER PEOPLE IN BEDLAM

After nearly 18 months in England, Margaret grew impatient to return to William in Antwerp. She had sent her first book to the printers and even dashed off another (Philosophical Fancies),[47] and Sir Charles’s estates had finally been released from sequestration, enabling him to buy back the family seats of Welbeck and Bolsover (though at a greatly inflated price) and stabilise the family’s finances. So on 16 February 1653, just two months before Poems and Fancies was due to publish, Margaret set off back to Antwerp, reluctantly leaving her brother-in-law behind as he had succumbed to a fever.

With the lovers rapturously reunited, and the publication of her first two books imminent, Margaret’s secret was out, and to her relief and gratitude she found in William a rare husband who entirely supported his wife’s new career. He understood her literary ambitions because he had them himself, though he had the grace to recognise that she was the better writer. He would encourage her, write prefaces and the odd line or verse for her, praise her (blindly, some said), and together they sent out her books to their illustrious friends and waited nervously for the responses.

Anticipation was high when Poems and Fancies was due to appear in April – though not necessarily for the right reasons. Dorothy Osborne wrote excitedly to her betrothed, Sir William Temple, ‘… first let me ask you if you have seen a book of poems newly come out, made by my Lady Newcastle?’ There was a concealed barb in her enquiry, however, as she clearly intended to despise it: ‘For God’s sake if you meet with it send it to me; they say tis ten times more extravagant than her dress. Sure, the poor woman is a little distracted, she could never be so ridiculous else as to venture at writing books, and in verse too.’[48] Margaret’s reputation as an eccentric had preceded her, and for many her decision to write only confirmed their prejudices.

Once they had actually opened the book, reader responses were mixed. The 2nd Earl of Westmorland, Mildmay Fane, was an avid fan, scrawling a poem in praise of Margaret’s talent inside his copy, while friends of the Cavendishes predictably gave it a glowing review. The highly cultured polymath and Dutch diplomat Constantijn Huygens wrote to a friend that it was ‘a wonderful book, whose extravagant atoms kept me from sleeping a great part of last night’. Others were less impressed. Once she’d got her hands on it, Dorothy Osborne felt entirely vindicated in her assumptions that Margaret must surely be mad, sniping to Sir William: ‘You need not send me my Lady Newcastle’s book at all, for I have seen it, and am satisfied that there are many soberer people in Bedlam. I’ll swear her friends are much to blame to let her go abroad.’[49] Margaret was not only compromising her womanly virtue by publishing a book; she was also guilty of an ‘extravagant’ kind of literature. Her ‘free and noble style’ that ‘runs wild about, it cares not where’[50] was scatterbrained, unrefined and hard to follow – it was all far too unconventional for Dorothy Osborne.

Another worrying response came from friend and courtier Sir Edward Hyde, who offered the ultimate back-handed compliment that a woman could surely not have written so clever, so learned, so masculine a book, with ‘so many terms of art, and such expressions proper to all sciences’.[51] The humble apologia, used so commonly by male writers and taken as intended – a rhetorical show of modesty aimed at endearing the writer to his audience – were in Margaret’s case being taken as an admission that she was so inept she must be passing off someone else’s work as her own. It was yet another accusation to add to the list of defences she was compiling for her next work, which was already underway.

On arriving back in Antwerp, Margaret had eagerly returned to a collection of essays she had started before her trip to England, but when she sifted through her papers, she was disheartened by what she found. It was obvious, even to her, that they were littered with errors and sagging under the weight of stunted arguments, half-baked ideas and distracting digressions. To revise them seemed too Herculean a task, so, true to form, in late 1654, she lazily published them anyway, as The World’s Olio – a concoction of observations on all manner of subjects, literary, political, social and philosophical, that made up the rich stew or ‘olio’ of the title – and, without correcting the proofs, sent it out into the world to be assessed, warts and all.

Hampered, still, by the misconception that she was not up to the task at hand, Margaret again used prefaces to excuse her faults and lay the blame on her gender: ‘It cannot be expected I should write so wisely or wittily as men,’ she insisted, ‘being of the effeminate sex, whose brains nature hath mix’d with the coldest and softest elements’.[52] She rejected the ‘great complaints’ from women, which were evidently becoming louder, that men had ‘usurped a supremacy’ over them since Creation. In fact, she argued the opposite, that ‘Men have great reason not to let us in to their governments, for there is great difference betwixt the masculine brain and the feminine’. While men had the strength of an oak, women, she wrote, were like willows, ‘a yielding vegetable, not fit nor proper to build houses and ships’.[53] They might exceed men in beauty, affections, piety and charity, but women didn’t have the judgement, understanding and rhetorical skills of men.