Полная версия

Roaring Girls

THE SINNER’S PENANCE

After all the brazen merriment and gleeful mayhem that has gone before, the diary culminates in an oddly remorseful end for Mary Frith, with the 74-year-old lying on her deathbed, weak and enfeebled and repenting her life of sin. She has fallen prey to a ‘dropsy’ – an excess of fluid – and as her body swells, she begins to see her condition as some kind of divine retribution for her life of vice, as every afflicted limb seems to ‘point out the wickedness every one of them had been instrumental in, so that I could not but acknowledge the justice of my punishment’. Her hands, however, remain unaffected – proof, she maintains smugly, that they were the ‘most innocent’ part of her body, because she never cut a single purse herself.

This tacked-on repentance scene may be incongruous, but it was vital to the acceptability of The Life and Death of Mrs Mary Frith as a work of public entertainment. The authors claim to have published Mary’s story not just because of the ‘strangeness and newness of the subject’, but for ‘the public good’. And if a celebration of criminality is to masquerade as morally instructive, rather than gratuitously sensational, then by the laws of storytelling it must culminate either in reform or condemnation.

In literature then, at least, Mary Frith recants at her death, claiming ‘with a real penance and true grief to deplore my condition and former course of life I had so profanely and wickedly led’. It’s a nice try, but coming from a woman who had so consistently revelled in her wrongdoing and smirked at disapproval, this dramatic moral conversion feels rather too neat to have occurred in real life.

More convincing is Mary’s appeal for us not to judge her too harshly, for, ‘If I had anything of the devil within me, I had of the merry one, not having through all my life done any harm to the life or limb of any person.’ Besides, she jokes, her illness is punishment enough, as it has finally accomplished ‘what all the ecclesiastical quirks with their canons and injunctions could not do’: made her abandon her doublet. Too swollen and sore to wear anything constrictive, she is grudgingly forced to ‘do penance again in a blanket’ and revert to her ‘proper’ female habit. Thus, in a moment sodden with symbolism, Mary’s ‘redemption’ is complete – she is a Roaring Girl no more.

In the diary’s final words, our heroine receives an unceremonial send-off, with Mary giving characteristically blunt instructions to be ‘lain in my grave on my belly, with my breech upwards’ so that she may be as ‘preposterous’ in death as she was in life. In reality, Mary’s burial was somewhat more dignified. Despite another dud claim in the diary that Mary made no will, on 6 June 1659, just a few weeks before she died on 26 July, she did just that – and it reveals that she was a prosperous woman. Under her married name of Mary Markham, she left £20 to a relative named Abraham Robinson – a substantial legacy given that a labourer might earn £10 in a year and a house could cost under £30[68] – and the remainder of her estate to her niece and sole executrix Frances Edmonds. Her bequests made provision for a decent funeral, and so on 10 August, as per her wish, she was given a Christian burial at St Bridget’s Church in Fleet Street – an end reserved not for the preposterous, but for the respected and well-to-do.

Mary Frith had died just a year shy of the Restoration – a new age of freedom and exuberance that would have suited her down to the ground. The Roaring Girl had fallen silent, and the play she had inspired had fallen out of fashion, yet her spirit would linger in the decades to come.[69] Her faux diary, published two years into Charles II’s reign, would reignite her legend, casting her as a fervent Royalist for a renewed Royalist era, but she was also present in more nebulous forms. She was there, for example, in the actresses who would walk the stage legally for the first time, and be applauded, not punished, for donning men’s clothes. She was there at the birth of the novel, in Daniel Defoe’s Moll Flanders, who early in the next century would be ‘as impudent a thief, and as dexterous as ever Moll Cut-purse was’.[70] And she was there in the new craze for criminal biographies that would perpetuate her myth still further – by adding highwaywoman to her list of misdeeds.[71] By the mid-eighteenth century she had taken her place in the rogues’ gallery of famous dare-devils – from Robin Hood to Jack Sheppard – whose lawless lives have always strangely enchanted us and whose crimes we can’t help but romanticise.

But when all the tall tales, exaggerations and embellishments are stripped away, what is left? We’ll never know exactly what measure of the legend of Moll Cutpurse was present in the real Mary Frith, but despite all the sanitisation, decriminalisation and simplification, the teasing snippets of the living, breathing Mary captured in court transcripts and eyewitness accounts bear a striking resemblance to the Mary of myth. What we find in every version of her is an audacious, idiosyncratic, irreverent woman who used her own brass and ingenuity to rise through the ranks, from common cutpurse to famed entertainer to entrepreneur to folkloric heroine, causing shock, anger and amusement along the way. In the misfits’ paradise on the peripheries of society, she found acceptance, safety, power and influence. She angered the authorities, captivated the playwrights, confused the biographers and divided the public. Hers was a life of constant peril and nagging insecurity, lived permanently on the edge – of respectability, legality, even sanity – and her strategy for survival was to hide in plain sight, wriggling and shape-shifting to exploit the loopholes, outfox her accusers and, whenever possible, get away with it altogether. This was a woman who wanted to be talked about but didn’t want to be caught, and by manipulating her fluid persona and feeding her own glorified myth, she made sure that the character who endured was not a hardened criminal but a lovable rogue. If this virtuoso of evasion slips through our fingers now, it’s probably because that’s exactly what she wants.

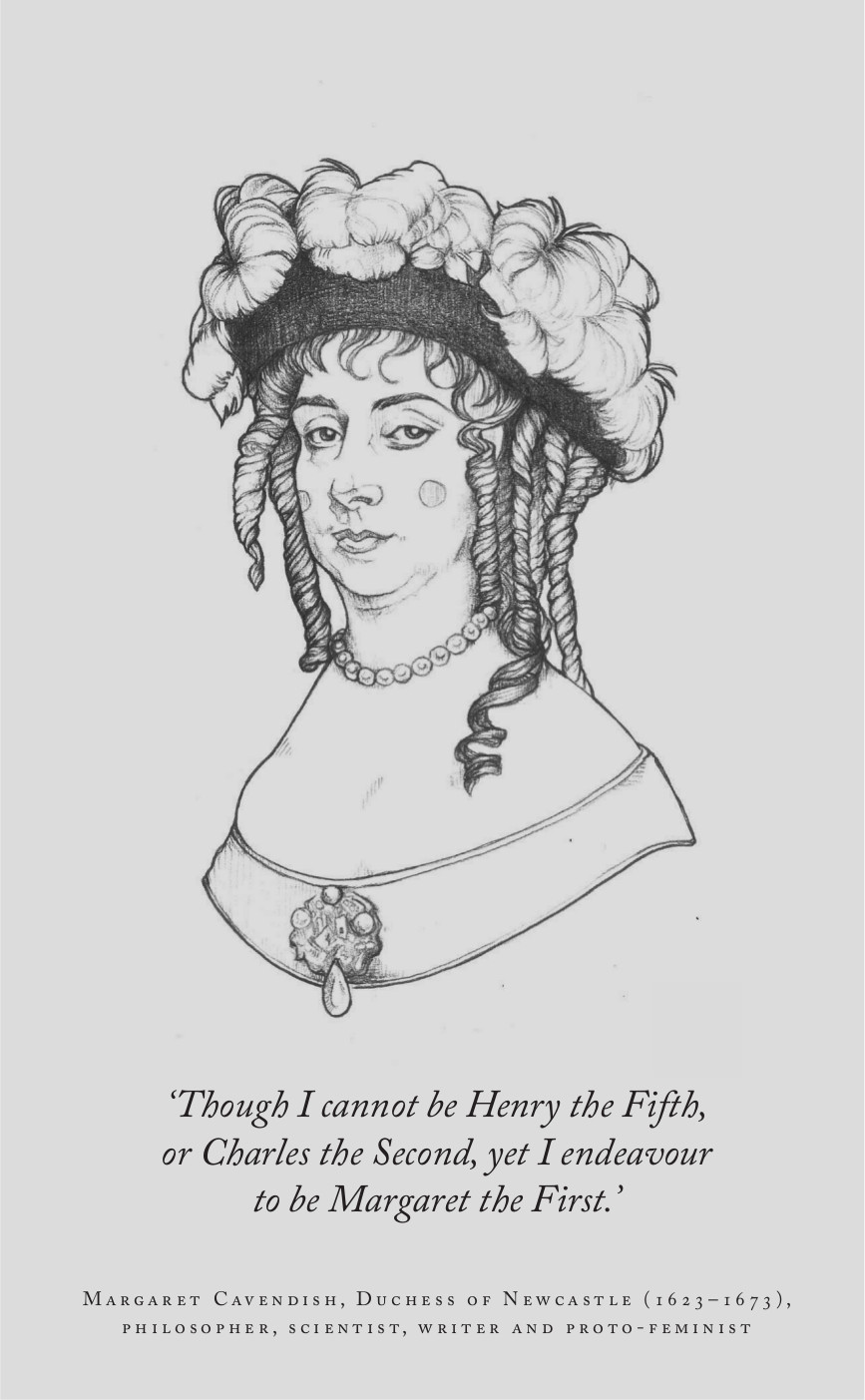

MAD MADGE

Samuel Pepys had been trying to catch a glimpse of the famous Duchess of Newcastle for weeks. It was spring 1667, the lady was in London on a rare visit from the Midlands and everyone was impatient for a sighting. The rumours had it that she would visit Charles II’s court on 11 April, and in the private pages of his diary, Pepys was on tenterhooks: ‘The whole story of this lady is a romance, and all she doth is romantic. Her footmen in velvet coats, and herself in an antique dress … There is as much expectation of her coming to court … as if it were the Queen of Sweden.’[1] So, along with the curious, of which there were many, to Whitehall Pepys went – only to leave disappointed, for the Duchess never appeared.

A fortnight later, on 26 April, he spied her distinctive black-and-silver coach and velvety footmen as he was travelling through London. He craned and peered and saw just enough to conclude that she was ‘a very comely woman’, dressed just as the gossips had described: velvet cap, mannish black juste-au-corps riding jacket, hair covering her ears, neck bared and a number of fashionable black patches scattered over her face.

This little snapshot wasn’t nearly enough to satisfy Pepys, so come 1 May he hastened to Hyde Park where she would be riding out along with the rest of the court in the May Day parade. Unfortunately, everyone else had the same idea, and the Duchess was so ‘followed and crowded upon by coaches all the way she went, that nobody could come near her’.

On 10 May they had another brief encounter as the Duchess made her way home through town to Newcastle House, in Clerkenwell. Spotting her carriage ahead of him, Pepys drove furiously in the hope of overtaking her, only to be thwarted yet again by a horde of ‘100 boys and girls running looking upon her’ who were also desperate for a peek. In the end, she arrived home before Pepys could catch up with her, but he wasn’t discouraged. ‘I will get a time to see her,’ he pronounced confidently.

And eventually, on 30 May, he did. The Duchess had boldly requested, and been granted, an invitation to the newly formed Royal Society – a Restoration temple to scientific advancement – and Samuel Pepys happened to be a member. There had been ‘much debate, pro and con’ by the fellows about whether or not a woman should be admitted at all. It had never happened before, and many were against it, some arguing that the Duchess’s reputation would expose the Society to ridicule, others that it surely set an undesirable precedent. But at length the motion was carried, the lady invited – and a fuss expected. ‘We do believe the town will be full of ballads of it,’ Pepys noted, and when the day came, he hurried to the Society’s headquarters, where he found ‘much company, indeed very much company, in expectation of the Duchess’, just like him.

At long last, Pepys had his chance to critique the woman at close quarters, and afterwards, as was his habit, he shared his impressions with his diary. His verdict, after all that, was damning:

The Duchess hath been a good comely woman; but her dress so antique, and her deportment so unordinary, that I do not like her at all, nor did I hear her say anything that was worth hearing, but that she was full of admiration, all admiration.

This lady, supposedly so learned in natural philosophy, had been shown the Society’s most innovative new experiments – ‘of colours, loadstones, microscopes, and of liquors’ – yet she’d had no insights or observations to offer whatsoever. In fact, she’d been virtually speechless. It had all been a great disappointment.[2]

Not many women could inspire such fascination on the one hand, and such scorn on the other. John Evelyn was also present that day and his diary entry was more succinct but no less scathing: ‘To London, to wait on the Duchess of Newcastle (who was a mighty pretender to learning, poetry, and philosophy, and had in both published divers books) to the Royal Society, whither she came in great pomp.’[3] And there was the truth of it: Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, had trespassed on male ground. She was a ‘mighty pretender’ to scientific and philosophical learning, who’d had the temerity to publish her writings, cultivate her own eccentric style and wilfully make a spectacle of herself. Every man in that room was thinking it: How dare she?

LADY BASHFUL

It’s little wonder Pepys was unimpressed with Margaret Cavendish’s behaviour that day at the Royal Society; it was precisely the kind of public social engagement that made her inwardly squirm. From childhood, Margaret Lucas (as she was born) had been debilitatingly shy, so uncomfortable and tongue-tied among strangers that they thought her ‘a natural fool’. But Margaret was no fool; addicted ‘to contemplation rather than conversation, to solitariness rather than society, to melancholy rather than mirth’, she was a dreamer, an observer, a sensitive soul.[4]

The one place she felt at ease as a girl was with her family, and the Lucases were one of the wealthiest in Essex. Descended from generations of self-made men, her father, Thomas Lucas, was something of a cavalier figure – in 1597 he was banished by Elizabeth I for killing one of her favourite courtiers in a duel, leaving his lover Elizabeth Leighton to bear the shame of giving birth to their illegitimate son. It would be six years, on James I’s accession, before Thomas was pardoned and the couple were able to marry. They settled at St John’s Abbey near Colchester and would go on to have a happy, respectable marriage and seven more children.

Margaret was the youngest, and although she would always regard her father as honourable and courageous, she would never know him personally – he was dead by the time she was two. Elizabeth took over the management of the Lucas estate (as the legitimate heir was not yet of age) and, as it happened, found she had a talent for the job. With the estate thriving under Elizabeth’s captaincy, Margaret had an impressive role model in her mother, whose ‘heroic spirit’ and ‘majestic grandeur’ she was always quick to praise. Her glowing account paints Elizabeth as a doting, lenient mother, who raised her children with all the proper virtues – modesty, civility and respectability – though not without some snobbery; they were never ‘suffered to have any familiarities with the vulgar servants’ and were always decked out to look ‘rich and costly’.[5]

While all this made for an idyllic childhood in Margaret’s eyes, it left her ill-prepared for the adult world in one crucial respect. As was standard among the rich gentry, the three Lucas boys were all formally educated and sent to Cambridge, while the five girls were given only a rudimentary education, by an unfortunate governess whom Margaret remembered only as ‘an ancient decayed gentlewoman’.[6] Like all high-born girls, the Lucas daughters were taught a few conventional feminine ‘virtues’ – singing, dancing, music, reading, writing, needlework – but even these were ‘rather formality than benefit’.[7]

Most of these accomplishments were of little use to Margaret. She had no interest in domestic pursuits and would later write with some pride: ‘I cannot work, I mean such works as ladies use to pass their time withal … needle-works, spinning-works, preserving-works, as also baking, and cooking-works, as making cakes, pies, puddings, and the like, all which I am ignorant of.’[8] Her interest lay elsewhere. For hours on end she would wander, lost in contemplation, and soon found that she preferred to ‘write with the pen than to work with a needle’. The blank page was a safe place, where her thoughts and ideas could roam freely. Even before she’d reached her teens she’d begun to write prolifically, filling 16 ‘baby-books’ with observations, poetry and stories – though she later dismissed them as childish ramblings, which perhaps explains why they haven’t survived.

Dress was another creative outlet, for Margaret had a bold sense of style and favoured creative, sometimes odd, ensembles – ‘especially such fashions as I did invent myself’ – to ensure that she came across as a true one-off, ‘for I always took delight in a singularity’.[9] As an introvert who found it difficult to express her personality verbally, Margaret allowed her idiosyncratic outfits (which often had a masculine edge) to do the talking for her, and this, too, would set her apart from most of her sex. It was all very well to indulge her whimsy and burgeoning imagination in the cossetted environment of St John’s Abbey, but in the wider world of seventeenth-century England, which valued obedience and conformity over flamboyance and originality, it left her rather more wilful and eccentric than was deemed acceptable in a woman.

The Lucases were a close-knit family. Margaret – a self-confessed physical coward who would jump at the sound of a gun and abhorred violence of all kinds[10] – was always so anxious that ‘an evil misfortune or accident’ might befall one of them that she would wake her siblings in the night to check they were still alive. Her fears were strangely prescient, for in 1642, when the Civil War broke out, there would be no escaping the unrest for the Royalist Lucases who, by then, were deeply unpopular in the Puritan county of Essex, thanks to their close involvement with Charles I’s regime.[11] When local anger erupted into the Stour Valley riots on 22 August, mobs descended on St John’s Abbey, ransacking and looting the Lucas home. The women in the house were imprisoned for several days while Margaret’s brother, John, now head of the family, was held at the Tower for a month for raising an army for the King.

Margaret was 19 at the time and blindsided by the violence, writing later that ‘this unnatural war came like a whirlwind’,[12] but her loyalty to Charles I was unshaken, not least because she had developed an intense fascination with his French queen. In Henrietta Maria, the Parliamentarians saw only a dangerous woman whose influence over the King encouraged popery and tyranny; Margaret, however, saw the heroic queen of her dreams. Nursing a desire to ‘see the world abroad’, she offered her services to her heroine as Maid of Honour, and although her siblings worried that their gauche little sister might make a fool of herself in the worldly, sophisticated court milieu, Margaret got her way. She arrived in Oxford, where the court had been transplanted for safety, in the summer of 1643.

It didn’t take long for Margaret’s new life to pall. The daily routine at court was tedious, involving little more than waiting around in the presence chamber for orders or standing to attention for hours on end. The freedom she’d had at home to write was gone and she now found herself constantly on show, which, as her siblings had predicted, left her so crippled by shyness that she was rendered almost mute. Maids were expected to charm court visitors with their dazzling wit and conversation, but Margaret, ‘dull, fearful and bashful’ as she was, felt it safer to play dumb and ‘be accounted a fool’ than to make a poor attempt at worldliness and ‘be thought rude or wanton’.[13]

So excruciating was this experience that Margaret would later fictionalise it in her 1668 play The Presence, in which she cast herself as Lady Bashful, the novice Maid of Honour who similarly gives the impression at Princess Melancholy’s court of being ‘a clod of dull earth’. But just as Lady Bashful turns out to be more than appearances would suggest, so Margaret felt there was a goldmine of ideas beneath her own gawky exterior. No doubt she was voicing her own aspirations when her alter-ego proclaims: ‘I had rather be a meteor singly alone, than a star in a crowd.’

There was little chance of being a meteor at court, and inevitably Margaret came to feel she’d made a mistake, but her mother refused all her appeals to come home, feeling ‘it would be a disgrace for me to return out of the court so soon after I was placed’.[14] She had no choice but to stick it out. And with the war intensifying, this would have life-changing consequences for young Margaret Lucas.

EXILES IN LOVE

By 1644, the Parliamentarians were gaining strength and the Queen, now pregnant with her ninth child, was in particular danger. Parliament had put a price on her head for high treason, citing her Catholic influence on the King as the primary cause of the war, so in April that year it became imperative for her to leave not just Oxford, but the country. With Margaret and the rest of her entourage in tow, Henrietta Maria went on the run, enduring a difficult birth and grave illness along the way. The group fled to Falmouth and on 30 June boarded a boat to the Queen’s native France, where they were confident of a warm reception.

But first they had to survive the voyage. Buffeted by storm winds, they lurched over the waves, the Parliamentarian ships in hot pursuit, pelting them with shots. Henrietta Maria was as impressive as ever during the onslaught, commanding that if it should come to it, the captain should blow up the ship’s ammunition store rather than allow them to be captured. Thankfully it didn’t come to that; they reached Brittany alive, only to be faced with the dangerous coastal cliffs that stood between them and safety. A treacherous scramble to the top followed, before they eventually found asylum at a small fishing village, a ragged and far from regal-looking bunch.

This daring great escape had shown Margaret rather more of the world than she had bargained for. At 21, she was suddenly an exile and a refugee, and the harrowing experience left an indelible mark on her psyche. Time and again in the stories she would later write, beautiful, virtuous young ingénues would endure perilous voyages and find themselves shipwrecked in strange lands.

Traumatised but safe, Margaret was living an isolated, miserable life with the Queen at King Louis XIV’s court at the Louvre in Paris when, in April 1645, William Cavendish, Marquess of Newcastle, arrived – a fellow Royalist exile who, having fled England in despair after a humiliating defeat at the Battle of Marston Moor, was also looking for comfort. On the surface, William was everything Margaret wasn’t: a courageous soldier and renowned horseman, confident, worldly, charming and, as the former tutor of Prince Charles, highly educated. He was also a ladies’ man, a rich widower and, at the age of 52, a full 30 years older than Margaret. And yet the pair had much in common: both were deeply romantic in nature and harboured high ideals, literary aspirations and a veneration of poetry, philosophy and plays. It wasn’t long before William was wooing Margaret with passionate verses on a daily basis.

Unused to male attention, Margaret was wary at first. Marriage was not on her mind – on the contrary, ‘I did dread marriage’, she would later admit.[15] To a free-spirited woman of the seventeenth century, it meant a caged life of household management, the dangers of childbirth and unquestioning submission to one’s husband, even if he turned out to be a drunkard, philanderer or tyrant. In later life, Margaret would even argue forcefully against marriage in principle, reckoning that ‘where one husband proves good … a thousand prove bad’.[16] Had circumstances been different, she might well have chosen the shame of spinsterhood over the shackles of marriage, but as it was, she fell in love and married William in a quiet ceremony at the end of 1645.

Young, timid Margaret Lucas was now Lady Cavendish, Marchioness of Newcastle. It sounded grand, but as a prominent Royalist, William’s primary Midlands estates of Welbeck Abbey and Bolsover Castle had been sequestered by Parliament, so in truth he had little to offer his new bride but his title. Margaret, in turn, was unable to access her substantial dowry of £2,000, as her brother, John, had been branded a ‘malignant’ by Parliament and also had his property confiscated, so when the couple set up home in William’s Parisian apartments, the only option was for William to flaunt his name, reputation and continued spending in the hope of reassuring creditors that he was a safe bet. The bluff allowed them to live well enough on borrowed money, but it was a precarious existence. More than once over the next few years the creditors’ patience would wear thin and William’s steward would bring the worrying news that ‘he was not able to provide a dinner’ for them that day.[17] On these occasions, pawning their belongings and borrowing money from William’s brother, or the Queen or anyone who would help them was the only recourse left.

Still, the Cavendishes put on a good show. William and his brother Sir Charles were enthusiastic, well-connected intellectuals who played host to some of the leading scholars, writers, scientists and philosophers of the day, including Thomas Hobbes and René Descartes. For Margaret, these soirées were accompanied by feelings of gnawing inadequacy, but by listening and observing (something she had always been good at), she found she could pick up second-hand all the latest philosophical theories and technological advancements to emerge from the Scientific Revolution that was sweeping through Europe. Margaret absorbed it all, quietly nursing a passion for big ideas and a longing to grapple with the invisible workings of the world. A woman with no education to speak of was suddenly an avid pupil at the cutting-edge of new thinking, and she found it utterly thrilling.

Less enthralling were Margaret’s new domestic challenges – not least her antipathy towards home-making and the fact that, as time went by, babies stubbornly refused to appear. Given that William had fathered numerous children by his first wife, the problem was assumed to be Margaret’s, so when there was still no sign of pregnancy two years into their marriage, her physician began to prescribe spa waters and a witches’ brew of herbs to be syringed into her womb every morning and night.[18]