Полная версия

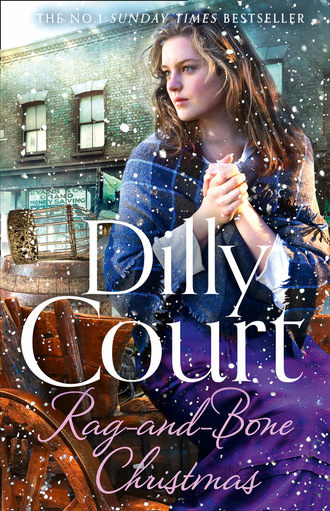

Rag-and-Bone Christmas

Sally sank down on the seat, watching in amazement as the dog licked Kelly’s tanned cheek. ‘Thanks, Kelly,’ she said reluctantly. ‘But I could have handled my horse.’

‘Sure you could, and you’d have ended up on the cobblestones with a broken collarbone,’ Kelly said, chuckling. He released Boney and thrust the wriggling dog into Sally’s arms. ‘I think this little lady is your problem.’

‘I don’t want her,’ Sally protested, turning her head as the little animal tried to lick her face. ‘She must belong to someone.’

Kelly put his head on one side, his periwinkle-blue eyes twinkling. He was obviously enjoying her discomfort. ‘Well now, I doubt that. Look at her, Sal. She’s all skin and bone and I daresay she’s running with vermin, but I’ll put her on the ground if you wish, although I can’t guarantee she won’t frighten your old nag again.’

‘Don’t you dare.’ Sally scowled at him, but she kept a tight hold on the dog. Kelly was right; she could feel the small terrier-type mongrel’s ribs through her matted fur, and her big brown eyes were enough to melt the hardest heart.

‘Where’s Ted?’ Kelly’s smile faded. ‘He must be off colour if he’s let you go out on your own.’

‘He’s all right,’ Sally said defensively. ‘Well, his rheumatics are playing him up, but he’ll be back on his rounds tomorrow.’

Kelly eyed her speculatively. ‘Tell you what, I’ll throw in some of the wood chippings that I don’t need.’

‘Why would you do that? You never do anything for nothing.’

He clasped his hands to his heart. ‘You do me a great wrong, mavourneen. Haven’t I always been a good friend to you and your respected pa?’

‘No, you haven’t. And stop calling me mavourneen, whatever that means. You would sell your own grandmother if you thought it would make you some money.’

He threw back his head and laughed. ‘I’d have to dig the poor old soul up first, and I doubt if she’d make much money in that state.’

‘You’re disgusting.’ Sally tried to sound angry but it was difficult with the dog writhing around in her arms and doing her best to lick her face.

‘Perhaps, but you want to laugh, I know you do. Anyway, your dada helped me out once when I was young and green, so call this repayment for his kindness.’ Kelly doffed his top hat and brushed a strand of dark hair back from his forehead. He put his hat on at a jaunty angle and strolled off to have a word with the foreman, who had emerged from the mill followed by two burly men hefting sacks of wood shavings.

Sally was tempted to refuse his generous offer, but the thought of returning home with little to show for a day’s work was even worse than accepting charity from Finn Kelly. She eyed him warily as he approached with a sack slung casually over his shoulder.

‘Wait here, mavourneen.’ He hefted the sack onto the cart as easily as if it had been filled with feathers. ‘There are a few more to come. You’ll thank me for this one day, you know you will.’ He winked and beckoned to the workmen, leaving Sally speechless for once. She quite literally had her hands full while the men loaded the sacks onto the cart as her new friend kept wriggling and trying to lick her face. In the end Sally set her down on a pile of rags.

‘Walk on, Boney.’ Sally did not look back to see if Kelly was watching her drive away, and she did not know whether to feel annoyed or grateful for his help. One thing was certain, he had added to her problems. What Pa would say when she arrived home with a flea-bitten mongrel was another matter.

Chapter Two

‘Are you out of your mind, girl?’ Ted glared at the small dog as it explored the small parlour, sniffing in corners and scratching at holes in the skirting board. ‘Take that little brute back to where you found it.’

‘I can’t do that, Pa. She’s obviously a stray and unwanted. She’ll end up at the bottom of the canal if I don’t look after her.’

‘Well take it down to the yard and give it a bath or we’ll be infested with fleas.’

‘Does that mean I can keep her?’

Ted shrugged and turned his head to stare into the fire. ‘Would it make any difference if I said no?’

Sally leaned over to drop a kiss on his grizzled hair. ‘Thanks, Pa. I’ll give her a bath and then I’ll go out and get us some hot pea soup and some fried fish as a treat.’

‘Where’d you get the money for such luxuries?’ Ted asked suspiciously.

Sally smiled triumphantly. ‘I sold five sacks of wood chippings to the factory where they specialise in fake raspberry pips to add to jam, and they make wooden seeds to boost the profits of the seed merchants.’

‘I don’t know if I hold with such practices.’ Ted sighed. ‘But we all have to get by, so well done, Sal. I could do with some hot soup, and I have a yearning for some fried fish.’

Sally picked up the dog. ‘It was all because of her. If she hadn’t startled Boney and made him rear up, I doubt if Kelly would have been so keen to help.’ She held the dog at arm’s length. ‘Raspberry pips earned us our supper and all because of you – Pippy. That’s a good name, Pa. We’ll call her Pippy because she’s brought us good luck.’

‘I’ve got several names for the mongrel and none of ’em repeatable in front of a young lady. Get the blooming animal bathed and then fetch my supper, girl. I’m starving.’

With a gleeful chuckle, Sally scooped up Pippy and took her downstairs to the stable, where she bathed her and rinsed her in diluted vinegar to kill the fleas. She left Pippy to shake and race round while she sorted the rags into their different piles, finally storing them in sacks beneath a tarpaulin in the back yard. When she had enough she would take them to the Rags Roper, and he would pay two to three pence a pound for the white rag, the coloured material being a little cheaper. The same price applied to the bones, some of which would be used in the manufacture of cutlery handles, while others were sold to the glue or soap factories. Rags would doubtless make twice as much, but that was the way business worked.

‘Come, Pippy,’ Sally called hopefully, having lost sight of the small dog amongst the crates, sacks and barrels in the yard. With a sharp bark Pippy emerged from behind a pile of snow-covered wood and bounded over to Sally, her pink tongue lolling out of the corner of her mouth as if she were laughing. Sally picked her up and gave her a cuddle, even though the dog’s fur was still damp. ‘You and I are going to be the best of friends, Pippy. But I’d better leave you with Pa while I go out to buy food, and I’ll bring back something for you, too.’

Next day Sally did the rounds with only Pippy for company. After her bath the previous evening, the little dog was now white and fluffy with brown ears and what seemed to be a permanent grin on her face. She sat upright on the seat next to Sally, and every time they stopped and were approached by a man, whether he was young or old, a foreman or a labourer, Pippy’s hackles rose and she growled deep in the back of her throat. Sally laughed it off, giving the dog a casual pat, but secretly she was pleased to have a protector. Pippy was small but she had needle-sharp teeth, and Sally was convinced that she would see off anyone who posed a threat. She had already proved her worth as a ratter and had found a nest in the yard, which she disposed of straight away. Pippy seemed intent on earning her living and Sally was delighted with her new friend.

Sally guided Boney through the crowded streets. People were rushing about concentrating on their preparations for Christmas Day and trade was poor, and no matter how loudly Sally shouted or how hard she rang her hand bell, there was little response from either householders or the businesses on her route. There was another reason for this, which became clear when she caught up with Kelly, whose cart was piled high with items he had collected.

Sally drew Boney to a halt. ‘What are you doing, Kelly? This is Pa’s round, not yours.’

He hefted a sack onto the cart. ‘First come, first served, mavourneen. You know that.’

‘No, I don’t. I thought you and Pa had a gentleman’s agreement.’ Sally bit her lip. She could tell by the smirk on Kelly’s face that he was going to make fun of her.

‘But, as you’ve often pointed out – I’m no gentleman.’ Kelly reached up to stroke Pippy, and to Sally’s chagrin, the small dog wagged her tail and licked Kelly’s hand.

‘She’s obviously a poor judge of character,’ Sally said crossly. ‘You’re not playing fair, Kelly. Pa’s done this round for years.’

‘Didn’t I help you out yesterday, mavourneen? You’ll have earned a few shillings from the sacks of wood chippings, I’ll be bound.’

‘You did help me yesterday, but that doesn’t excuse what you’ve done today.’ Sally glanced over her shoulder at the few things scattered on the bottom of the cart. ‘It’s getting late and that’s all I have to show for a day’s work.’

But Kelly did not appear to be listening. He was studying Sally’s horse and a frown creased his brow as he ran his hands over Boney’s body. ‘You’ll be lucky to get this fellow back to the stable tonight.’

‘Why? What’s the matter with him?’ Sally climbed down from the driver’s seat and went to stand beside Kelly. ‘He’s panting a bit, but he’s an old boy.’

Kelly gave her a pitying glance. ‘I’ve been handling horses all my life, girl. I know when a heavy horse like him needs to be put out to pasture, or sent to the knacker’s yard.’

‘Never!’ Sally cried angrily. ‘I couldn’t do that to him.’

‘Tell your da what I said, Sally. He’s had enough experience of horseflesh to know that I’m telling the truth.’

‘But without Boney we have no way of earning a living.’

‘I’m sorry. I really am, but this is no business for a young woman like you. It’s a rough old world and there aren’t too many gents like me around.’

Sally knew he was mocking himself, but she was too upset to appreciate his sense of humour. ‘Thanks, Kelly. I mustn’t keep you, and I need to get on. Tell me where you’re going and I’ll drive in the opposite direction.’

He shrugged. ‘I’m finishing for the day, mavourneen. There’s a Christmas bowl of rum punch waiting for me at the Nag’s Head, so you can have the rest of the round, but take my advice and don’t push the old horse too far.’ Kelly patted Boney on the neck before heading back to his cart. He climbed nimbly onto the driver’s seat. ‘Remember what I said.’ He drove off before Sally had a chance to respond.

She stroked Boney’s nose. ‘You’ll be all right, won’t you, old chap? I wouldn’t do anything to hurt you.’ She bent down and picked up Pippy, placing the small dog in the footwell before resuming her seat and taking the reins. ‘Walk on, Boney.’

Sally was careful not to push the aged horse too far, and she did manage to pick up several sacks of rags and some scrap iron, but as she drove homewards along a snowy Great College Street she became aware that Boney was flagging. He stumbled a couple of times and eventually came to a halt, his head down and his breathing laboured. Sally leaped to the ground and went round to hold the reins, talking to him softly, as she had always done, but he seemed oblivious to everything. They were only a few yards away from the Veterinary College and Sally walked very slowly, leading Boney by the head. Traffic thundered past them, some of the drivers shouting impatiently, while others whipped their horses to a dangerously brisk pace in order to get past them.

‘Ignore them, Boney,’ Sally whispered, stroking his soft muzzle. ‘I’ll get help and you’ll be as right as rain.’ She was not sure whether she believed her own words, but it kept her spirits up until they were inside the gates of the college. She left Boney, safe in the knowledge that he would wait patiently for her return, but his breathing was even more laboured than before and she feared the worst. She hurried across the courtyard and entered the main building, gazing around in near panic. Pippy had followed her and she growled menacingly as the doorman approached. His expression was not encouraging. ‘What do you want, lad? This here is a college for gentleman veterinarians. I think you’re in the wrong place. You’d best go and take that mongrel with you.’

‘Pippy, sit,’ Sally commanded, and to her surprise the dog obeyed, although she kept eyeing the doorman and growling deep in her throat. Sally cleared her throat ‘I’m not a boy, and I need help, mister. My horse is very sick and it’s snowing. He’ll freeze to death in these conditions.’

‘Like I said, miss. This is a teaching institution, the best in Europe, so I’m reliably told.’

‘I’m sure it is, but this is an emergency. Isn’t there someone who could take a look at my animal? I think he might die and then what would you do. He’s in the courtyard.’

‘Very irregular, miss.’ The doorman shook his head, clicking his tongue against his teeth. He turned his head at the sound of footsteps. ‘Ah. This gentleman might set you right. Mr Lawrence, sir. This young lady says her sick horse is in the courtyard. I’ve told her this ain’t no animal hospital, but she won’t budge and she’s got that ferocious animal with her.’

Sally spun round and stared at the young man. His tweed jacket and country-style clothes were familiar, and when he came closer she remembered where she had seen him. ‘It’s you,’ she said lamely.

‘The young lady with the basket of pies.’

‘Yes, thank you for reimbursing me,’ Sally said politely.

He held out his hand. ‘Gideon Lawrence. What can I do for you?’

‘I’m Sally Suggs and my horse is sick. I think he’s dying and I don’t know what to do for him.’

‘I told her this is a teaching institution, sir.’ The doorman pursed his lips, glaring at Sally in open disapproval. ‘No dogs allowed.’

‘Nevertheless, Hopkins, I am a qualified veterinary surgeon, and I will do my best for the poor animal. Come with me, Miss Suggs.’

More relieved than she cared to admit, Sally followed him outside into the courtyard, with Pippy gambolling at her heels. She stood back watching in awe as Gideon examined Boney, talking softly to calm the frightened horse.

‘What’s wrong with him?’ Sally asked anxiously. ‘I’ve never seen him like this.’

‘How old is he?’

‘Nearly twenty, so I was told.’

‘That explains it then.’ Gideon glanced at the goods in the cart and shook his head. ‘I’m afraid his days of working the city streets are at an end, Miss Suggs.’

Sally stared at him in dismay. ‘But he’s well looked after, Mr Lawrence. Can’t you make him better?’

‘I can do nothing to combat old age. This old chap needs to be put out to pasture or …’

‘No,’ Sally cried passionately. ‘Not the knacker’s yard. I’ll find somewhere for him, although I don’t know how I’ll go about it.’

Gideon eyed her thoughtfully. ‘Where is he stabled at present?’

‘My pa rents a scrap yard in Paradise Row. We live there, so there’s always someone to look after the horses.’

‘Well, this old chap needs a good rest, but I don’t think he’s going to make it back to Paradise Row this afternoon.’

Sally threw her arms around Boney’s neck and hugged him. ‘It will break Pa’s heart.’

‘You say you have another horse. Will you be able to continue your business?’

‘With Flower?’ Sally chuckled in spite of her heavy heart. ‘My Flower is a thoroughbred Andalusian. She’s a delicate creature and she couldn’t pull a cart to save her life.’

‘I’m sorry.’

Sally met his puzzled gaze with a smile. ‘You’re wondering why a rag-and-bone man would own a valuable animal like Flower.’

‘I wouldn’t have put it quite like that, but I suppose I was thinking along those lines.’

‘My mother was a performer at Astley’s Amphitheatre. She taught me to ride before I could walk, but a bad fall put paid to her career.’

‘Again, I’m very sorry to hear that.’

‘She died a couple of years later.’ Sally stared down at her booted feet. Talking about her loss always brought tears to her eyes. She sniffed and took a deep breath. ‘I was just fourteen at the time, and I’ve looked after Pa ever since.’

‘Was Flower your mother’s horse?’

Sally shook her head. ‘Ma’s horse Gaia was sold to the owner of Astley’s, and he allowed us to keep her foal in part payment, as he owned the sire – another Andalusian. Pa wanted to take the money instead, but he saw how much it meant to me, and he allowed me to keep Flower.’

‘She must be a very special horse. Andalusians are almost impossible to come by these days.’

‘She means so much to me. I used to dream of following in Ma’s footsteps and riding Flower in front of adoring crowds at Astley’s, but I have to be practical and look after Pa.’ Sally looked away. ‘I don’t know why I’m telling you all this. It’s just a childish fantasy.’

‘I can’t say I’ve ever felt so strongly about anything.’ Gideon gave her a searching look. ‘But perhaps I can help you, after all.’

‘Really? Can you give Boney something to make him strong again?’

A smile crinkled the corners of Gideon’s warm brown eyes. ‘I wish that were possible. But what I can do is to keep Boney here for a while. He’ll have every care taken of him, and he’ll be good practice for my students.’

‘That’s kind of you,’ Sally said doubtfully. ‘But I have to get the cart home. I can’t pull it myself.’

‘I should think not.’ Gideon frowned thoughtfully. ‘We have several horses in the stables here. If you promise to return him tomorrow, I’ll let you have Major. He’s a heavy horse like Boney, and he’ll get you and the cart back to Paradise Row, but he belongs to the college so I’m afraid you won’t be able to use him on your rounds.’

‘I understand.’ Sally was torn between wanting to take Boney home and the practicality of returning the heavy cart to the stable.

‘Boney might well have a heart attack and die, if you make him pull that cart back to Paradise Row. He’ll be well cared for here, but he really needs to spend the rest of his days at pasture.’

Sally sighed and shook her head. ‘That’s not possible. I wish it were.’

‘I might have somewhere in mind.’

‘It’s very kind of you but we can’t afford to pay.’

‘That wouldn’t be a problem, but you don’t want to leave Boney here, I can see that; however, I give you my word that he will have the best attention. We can’t turn back time, but we can ensure that the old fellow has a chance to recover.’

‘Yes, I suppose so. I don’t want to sound ungrateful, but he’ll be scared without me. I’ve slept in the stable with him before now, if he’s been poorly.’

‘If you try to take him home now, I doubt if he’ll make it to the end of the street. It’s up to you.’

‘Pa will be very upset.’

‘Would you like me to come with you? I could explain things in detail to your father.’

‘No, thank you. I’m the best one to break the news to him. We’ll manage somehow.’

‘Then let’s unharness the poor old chap and I’ll take him to the stable. If you’d like to come with me, I’ll introduce you to Major. He’s a docile animal, used to being the centre of attention, so he won’t give you any trouble, which is more than I can say for your dog.’ Pippy had been racing around the courtyard, but she came to a halt at Gideon’s feet and he bent down to scoop her up. ‘Behave, little lady.’

‘I’m sorry,’ Sally said hastily. ‘I only came across Pippy yesterday and she adopted me rather than the other way around. But she’s a good dog really.’

‘I can see that. She’s young and she’s intelligent. She just needs a firm hand.’ Gideon passed Pippy to Sally. ‘I’ll look after Boney, but you’d better not bring your dog into the stables. She’ll no doubt cause mayhem there.’ He unharnessed Boney, leaving Sally to secure Pippy to the cart with a length of rope.

‘Stay there and be a good girl,’ Sally said firmly. ‘I’ll be back in a minute.’ She shot a sideways glance at Gideon. ‘I suppose you think I’m silly, talking to a stray dog like this.’

He laughed. ‘No, you’re quite right. She might not understand the words yet, but the tone of your voice will no doubt be a comfort to her. Follow me, Miss Suggs.’

When Sally broke the news to her father she could see that he was more upset than he would admit.

‘Boney has done us well over the years,’ he said gloomily. ‘We old men should retire.’

‘Don’t say things like that, Pa. You’re not old.’

Ted shook his head. ‘I feel ancient sometimes, love. My whole body aches and I know I ain’t the man I was. Me and Boney should be put to pasture together.’

‘I won’t allow you to think that way.’

‘This is the end of our business, Sal. We can’t carry on without Boney.’

Sally thought of Major, the splendid Shire horse who was now eating his way through as much hay as poor old Boney might consume in several days. She would have to return Major to the college tomorrow, but what then? The truth hit her like a lightning bolt. ‘No, Pa. We can’t sell Flower.’

‘I’m sorry, love. It’s that or the workhouse for us. You know it’s the last thing I would want …’ Ted broke off, his eyes reddened and moist with unshed tears. ‘Don’t look at me like that, Sal. What else can we do?’

‘I don’t know. Anything, but that. I could get a job at Astley’s like my mother. I can ride well.’

‘You’d be up against real professionals, Sal. Your ma was a wonderful performer, but in the end the riding killed her.’

‘The fall did that, Pa. She could have fallen downstairs and hurt herself just as badly.’

‘Well, all that is in the past, sad as it is. I hope to join your mother one day soon, and then I’ll be a happy man.’

‘Don’t talk like that.’ Sally gazed at her father and saw him suddenly as an old man. This last shock seemed to have sapped the life from him, and he appeared to have shrunk like a wizened apple. ‘Forget what I said. We’ll get another heavy horse. Maybe I can sell something to raise the money.’ She looked round the small room with its shabby sofa and worn armchair. The square table set beneath the window was propped up by a book under one broken leg, and the clock on the mantelshelf had stopped, yet again. Like almost everything else in the room it seemed old, tired and ready to go back to the scrap heap.

‘You’ll have to face it, love. Flower has to go to Tattersalls. They’ll get a good price for her, and maybe Kelly would like to make an offer for the cart.’

Sally felt her whole world slipping away beneath her feet. She sat down beside her father and clutched his hand. ‘I can do the round until you’re better, Pa. We’ll get another horse and I’ll work twice as hard, you’ll see.’ She stroked Pippy, who had leaped upon her lap and was trying to lick her face.

‘That dog will have to go, too.’ Ted glowered at Pippy. ‘We can’t afford to feed her, and she’s no use to man nor beast.’

‘She’s a good ratter,’ Sally protested. ‘She’ll earn her keep, as will I.’

‘That’s enough.’ Ted shook his hand free from her grasp. ‘I knows you mean well, love. But the rag-and-bone business ain’t for a young woman on her own, and I don’t see meself going back on the rounds.’

‘You’ll get better, Pa. We’ll get the doctor to look at you and maybe he can give you something to ease your aching bones.’

‘Maybe.’ Ted raised himself with difficulty. ‘I’m going to me bed, love.’

‘Good night, Pa.’ Sally watched her father hobble towards the door which led to his tiny bedroom. Her own bed was beneath the eaves on the opposite side of the building to where her father slept, with the living room in between. In the summer she could look through the cracks where the roof tiles had slipped and see the stars. In winter she had to wear her coat in bed and wrap a shawl around her head. If it rained she slept beneath a tarpaulin, and no matter how many times they reported the leaking roof to the landlord, nothing had ever been done. She knew that she would sleep little that night, and instead of getting ready for bed, she went downstairs to the stable with Pippy at her heels. Flower greeted her with a soft whinny and Major turned his head to give her a blank stare.

‘I can’t do it, Flower,’ Sally said softly. ‘I won’t let you go, no matter what happens.’