Полная версия

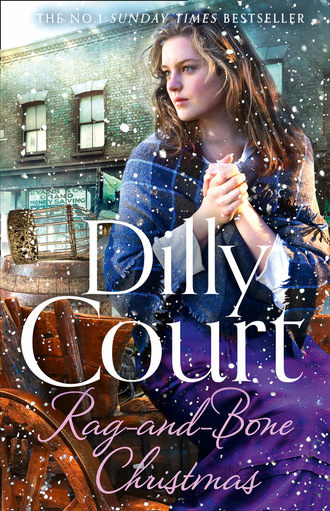

Rag-and-Bone Christmas

RAG-AND-BONE CHRISTMAS

Dilly Court

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2020

Copyright © Dilly Court 2020

Jacket Photographs: © Gordon Crabb/Alison Eldred (Girl); Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo (background front cover and back cover); Shutterstock.com (all other images)

Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2020

Dilly Court asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008287870

Ebook Edition © March 2020 ISBN: 9780008287887

Version: 2020-09-02

Dedication

In fond memory of Pippy and Beasley, two canine best friends.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Read on for a sneak peek at Dilly’s brand-new book The Reluctant Heiress

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Dilly Court

About the Publisher

Chapter One

Paradise Row, Pentonville, London. December 1865

Snow was falling fast, but even before it floated to the ground its pristine whiteness was tainted by pollution from the black-lead works, and soot from the factory chimneys. The thunderous sounds from the iron foundry, situated a little further along Old St Pancras Road, added to the general hubbub, and steam engines roared in and out of King’s Cross railway station.

Away from all this, as though in a different world, it was quiet and peaceful inside the stable, and comparatively warm. Sally Suggs worked tirelessly to keep the stalls spotlessly clean, and the two animals stabled there were fed only the best hay, with plenty of fresh water to drink. Pa always teased Sally and said it was because she had been born in the stable that she had such an affinity with horses, but she was convinced that she had inherited her talent as a horsewoman from her late mother. Emily Tranter had been a famous equestrienne, who had delighted audiences at Astley’s Amphitheatre until she met and fell in love with young Edward Suggs, the rag-and-bone man.

‘Ain’t you done here yet, girl?’ Ted hobbled in from the yard and took off his cap, sending a dusting of snow onto the floor.

‘Nearly finished, Pa. Then I’ll go to the shop and get us something for our supper.’

‘It’ll be dark soon, love. You know I don’t like you walking out on your own at night, and it’s snowing harder than ever.’

Sally turned to him with a chuckle. ‘Pa, I’m nearly twenty. I’m not a little girl any longer.’

‘You are to me, my duck. You always will be, and I ain’t as fit and healthy as I used to be. My old pins ache something chronic, especially when it’s bitter cold like this.’

‘You should be in the parlour sitting by the fire,’ Sally said severely. ‘You’ve done your bit for today. I won’t be long, I promise.’ She reached up to pat Flower’s sleek neck as the horse nuzzled her shoulder.

‘You’d bring that blooming animal upstairs if she could manage them.’ Ted grumbled but his grey eyes were twinkling. ‘You wrap up warm if you’re going out,’ he added as he opened the door that led to a narrow flight of stairs. His heavy footsteps echoed round the stable, and then there was silence.

‘I would stay with you all night, Flower,’ Sally said, kissing the horse’s soft muzzle. ‘But I have Pa to look after as well as you.’

Flower whickered gently as if in reply, and with a loving pat, Sally turned her attention to Boney, the ageing heavy horse who had pulled their cart through the London streets for the last fifteen years. He was still eager to work, but age was catching up on him and sometimes his joints were stiff, causing him to lumber over the cobblestones as if each step caused him pain. Sally had tried all manner of remedies, including poultices and doses of celery seeds, but in reality she knew that Boney’s working days were numbered, and in a year or two he ought to be put out to pasture – the alternative was the knacker’s yard, and that was unthinkable. Her dream would be a country cottage where her father could enjoy a long retirement, and Boney could end his days in peace.

Sally finished her work in the stable and went outside to make sure that the gates were locked and bolted. Although the items in the yard had been discarded by the former owners they still had a market value, and there were always those who preferred to steal rather than earn their living by honest toil. She hurried back to the comparative warmth of the stable and extinguished the candles. Fires were all too common in places such as this, and everything had to be kept out of reach of the horses. A lamp left burning might easily be overturned by a frisky horse, and the whole place would go up in flames.

Sally gave Flower a last affectionate pat on the head before slipping on her well-worn tweed jacket, and tucking her hair into one of her father’s old caps. Fashion had little or no place in Paradise Row, especially when working in the scrap yard or the stable. Ever practical, Sally wore a pair of patched breeches that she had come across in one of the sacks, and a pair of lace-up boots that had also seen better days, but were still reasonably wearable. She picked up a wicker basket and let herself out into the street, locking the door behind her. A cold wind sent wisps of hay, rotting cabbage leaves and scraps of paper scudding down the road, adding sharp teeth to the swirling snow, and she pulled up her collar, wrapping her arms around her thin body.

‘I was hoping I’d be in time to catch you, Sal.’

A cheery voice made her stop and turn her head. ‘Oh, it’s you, Josie. Is it your half day?’

Josie’s wide mouth curved in a mischievous grin. ‘I slipped out when Cook fell asleep after drinking half a bottle of gin.’

‘She’ll get caught one day and you’ll be in trouble for keeping the truth from Mrs Grindle.’

‘I don’t care. I’m looking for another position anyway. I’m fed up with working all hours for less than eight pounds a year, and only one half day off a month. The Grindles treat us servants like slaves.’

‘What else could you do, Josie? You might end up worse off with a master who beats you, or …’ Sally lowered her voice as they passed a group of workmen, all of whom were ogling them and whistling. ‘You know what I mean, and they’re a fine example of what men think of girls like us.’

Josie tossed her head. ‘I spit on their kind. One day I’m going to marry a decent man who’ll treat me like a lady, not a common slut. I got me pride, Sally.’ She poked her tongue out at a man who had loitered behind his mates to proposition her, but he laughed and slapped her on the buttocks.

‘Come home with me and have a bit of supper,’ Sally suggested hastily. ‘Ignore him, Josie. His sort aren’t worth bothering about.’ She turned her head to glare at the man, who was laughing uproariously. ‘I know your wife, Sidney Jones. She won’t find it funny when I tell her what you just did to my friend.’

His answer was lost in the loud blare of a factory hooter in the region of the railway station.

‘I don’t care about the likes of him,’ Josie said, wrinkling her snub nose. ‘Ta for the invite to supper, love, but I’m meeting Ned when he comes off his shift at the gas works.’

‘You do know that he’s married, don’t you, Josie?’ Sally came to a halt, grasping her friend’s hand. ‘I’m not judging you, but I don’t want to see you get hurt.’

Josie laughed and squeezed Sally’s fingers. ‘You worry too much. It’s just a bit of fun. We’ll shelter under the railway arches and have a kiss and a cuddle, and then he’ll go home to his missis a much happier man, and I’ll go back to Grindles’ hell.’ Josie’s smile faded. ‘I like him a lot, Sally. He’s the best thing that’s happened to me in years.’

‘And that’s what worries me. Don’t get too involved – you’re the one who’ll suffer when it ends.’

‘Ta for the advice, but I’m a big girl now. He’s good for a laugh.’ Josie pulled her shawl round her head and hurried off in the direction of the gas works, leaving Sally to make her way to the grocer’s shop on the corner. Old man Jarvis was behind the counter as usual, and his gloomy expression seemed to have been painted indelibly on his wrinkled features. His bald pate gleamed in the lamplight as did the tip of his red nose. Sally had always suspected that he kept a bottle of spirits hidden beneath the counter, taking a nip or two when he thought no one was watching. The smell of gin hung in the cloud above his head, mingling with the aroma of roast coffee beans and the sawdust that was scattered over the bare floorboards.

Sally purchased a loaf of bread and two meat pies.

‘Will that be all?’ Jarvis demanded testily. ‘Got some fresh eggs brought in from a farm today. You won’t get none tastier than these.’

Sally hesitated. Pa was always partial to a boiled egg for his breakfast and that justified the extra expenditure. ‘I’ll take two, please.’

Jarvis wrapped the eggs in a page torn from yesterday’s copy of The Times and placed them in Sally’s basket. ‘That’ll be elevenpence ha’penny.’

Sally placed a shilling on the counter and waited for the halfpenny change. It was the last of the money that Pa had given her from the profit he made selling the last lot of rags to Rags Roper, the cloth merchant. She put the halfpenny in her purse.

‘Good evening, Mr Jarvis.’

‘Good evening, Miss Suggs.’

She left the shop and pulled her cap down over her forehead in an attempt to shield her eyes from the driving snow. The horse-drawn traffic rumbled past and the clock on the St Pancras Church was booming out the hour. It was no wonder she failed to hear the approaching footsteps. She cannoned into the man who was struggling to open his umbrella, and the force of the encounter sent her purchases flying out of the basket onto the snowy pavement.

‘Look where you’re going!’ Sally cried angrily. ‘That’s my supper lying on the ground.’

‘You barged into me, you stupid boy.’ The man lowered his umbrella, staring at her in the flickering light of the street lamp. ‘Oh, I’m sorry, miss. Are you hurt?’

‘No,’ Sally said reluctantly. ‘But the eggs are smashed and the pies are covered in slush. That’s our supper you’ve ruined and my pa will be furious.’ She tilted her head back to glare at the man, who was dressed like a country gentleman, which was decidedly out of place in this part of London. He was younger than she had supposed, and his rugged features were creased in a worried frown.

‘I am truly sorry.’ He held out his hand. ‘I was also at fault. You must allow me to reimburse you for the groceries.’

Sally looked down at the shattered eggs and pies; even if she had wanted to rescue them, she was too late. Two half-feral dogs sprang from seemingly nowhere and pounced on the food, growling ferociously as they vanished into the shadows with their bounty. She had eaten very little that day and the temptation to accept his offer was overwhelming.

‘Thank you,’ she said reluctantly. ‘It cost me elevenpence ha’penny.’

He put his hand in his pocket and took out a handful of small change. ‘Here’s a shilling, with my apologies.’

She took the halfpenny from her purse and exchanged it for the shiny silver coin. ‘Normally I wouldn’t accept,’ she said gruffly. ‘But as it happens I’m a bit short of the readies at the moment, so thanks again.’ She turned away in case he changed his mind and she hurried back to the shop to repeat her order to a surprised Mr Jarvis.

‘You’ve taken your time.’ Ted looked up from the crumpled newspaper he had been attempting to read by the light of a candle stub and the glow from the coal fire. ‘I’m starving. What kept you?’

Sally placed her basket on the table and unpacked the contents. ‘I had a slight mishap on the way home from old Jarvis’s shop, so I had to go back and get two more pies and a couple of eggs.’ She took out a small cob loaf. ‘And he must have felt sorry for me because he threw in the bread for nuppence.’

‘It’s probably stale then. Frank Jarvis never gives anything away, the old skinflint.’ Ted smoothed the creased newspaper, peering short-sightedly at the print. ‘One day I’ll make enough money to buy a paper every day, instead of reading what other folks have thrown out.’

‘Yes, that would be nice, Pa.’ Sally took off her sodden jacket and cap, shaking out her long, dark hair.

Ted eyed her curiously. ‘You still haven’t told me what happened between here and Jarvis’s shop.’

‘It was snowing so hard that we didn’t see each other until it was too late and he nearly knocked me over – well, to be fair I wasn’t looking either. Anyway, the food went flying and landed on the pavement, and then, to cap it all, a couple of stray dogs wolfed the pies.’

‘But you wasn’t hurt, love?’

‘Only my pride, Pa. And the fellow paid up, so I went back to the shop and we have supper after all.’

‘You was lucky to meet a gentleman, that’s all I can say. There’s many who wouldn’t be so generous.’

Sally took two plates from the dresser that her father had constructed from an old chest of drawers and some wooden shelving. ‘Here you are. Enjoy the pie and I’ll put the kettle on.’

‘You’re a good girl, Sal. I don’t know what I’d do without you.’

She smiled and placed the kettle on the trivet in front of the fire. ‘You’ll never have to find out, Pa. We’re a team, you and me, not forgetting Boney and Flower, of course.’

‘Sit down and eat your supper.’ Ted shifted uneasily in his chair. ‘I think you’ll have to take the cart out on your own tomorrow, love. My joints are playing up something terrible tonight. I doubt if I’ll be able to get downstairs in the morning, let alone do me rounds.’

‘It won’t be the first time, Pa. I know the route like the back of my hand.’

‘Just leave the heaviest things for Kelly. He’ll love that,’ Ted added grudgingly. ‘He’s always trying to get one up on me.’

‘Don’t worry. I can handle Kelly. He won’t get the better of me. That’s a promise.’

Next morning Sally was up before dawn. It was cold and dark in her tiny bedroom, with space only for a narrow iron bedstead and a single chest of drawers, which doubled up as a washstand. She dressed hastily in her working clothes and went downstairs to the back yard to use the privy and draw water from the pump. It had stopped snowing, and a hard frost had turned the surface into a sheet of ice.

Her first task was to clean the stable, and then she fed and watered the horses. Flower always greeted Sally with affectionate nuzzling of her hand, and Boney pawed the ground, waiting for his food. When she was satisfied that the animals wanted for nothing, she went upstairs to do her chores before starting the day’s work. Having cleared the ashes from the grate she lit the fire and put the eggs on to boil while she toasted slices of stale bread. There was a scraping of butter left in the dish, and she spread it on a piece of toast, cutting it into fingers as her father had done for her when she was a child.

The back room where Ted slept in a truckle bed below the eaves was little bigger than a cupboard. The accommodation over the stable was not spacious, but it had been the only home Sally had ever known, and she had done her best to make it as comfortable as limited means would allow. The gaily coloured patchwork coverlet was all her own work, and had taken many hours of cutting squares from the clothes discarded by the wealthier people in the neighbourhood, and even more hours spent patiently sewing them together. Sally was proud of her efforts and the quilt brightened the small room.

‘How are you today, Pa?’ Sally asked anxiously as she placed the tray on the floor beside his bed.

Ted heaved himself to a semi-sitting position. ‘You know how it is, love. I’d get up if I could but me joints are playing up something chronic in this cold weather.’

Sally helped him to a sitting position and placed a couple of pillows behind him. Despite having hung them out last summer for days on end in the fresh air, there was still a lingering odour of the sickroom in the fabric and feather stuffing. It was fortunate that her father had lost his sense of smell after many years of handling noxious substances when he had worked on the great dust heap at Battle Bridge before its eventual removal.

‘There, is that better?’ She placed a tray on his lap. ‘I’m afraid that’s the last of the butter, but I’ll get some this evening on my way home. Let’s hope I have a good day.’

‘Don’t let anyone take advantage of you, love. I’ll try to get down to the yard later on. If I can just sort out the white material from the coloured rags it’ll be a help. You get more money if the stuff isn’t dyed.’

‘Yes, Pa. I know that, but you ought to stay indoors in weather like this. We don’t want you having a fall and breaking your leg or worse.’

‘But I don’t like leaving everything to you, love.’

‘Don’t worry about me, Pa. I know what I’m doing and I’ll be fine.’

‘You’re a good girl, Sal. I’m lucky to have you for a daughter.’

She leaned over to drop a kiss on his grey head. ‘I love you, too, Pa. Now eat up and I’ll bring you a nice hot cup of tea before I go out.’

* * *

Half an hour later Sally had Boney harnessed to the cart and she drove out onto Paradise Row. It was still early but the night-shift workers were shuffling home to their beds, barely acknowledging their neighbours, who were hurrying to their place of employment to begin their twelve- or fourteen-hour day. The street was lined with tenements, housing countless numbers of lodgers. There were large families crowded into one small room, single working men, who came off the night shift and climbed into a bed recently vacated by the workers who had left for the day’s toil in the manufactories. Mothers with babies in their arms and toddlers clinging to their skirts packed their older children off to work anywhere they could earn a few pennies a day. There was little money to go round in Paradise Row and many women, whether married or single, were forced out onto the streets at night in sheer desperation, selling themselves to anyone with a few coppers to spare. Others were addicted to drink or opium, but Sally had seen too much poverty to be judgemental. She raised her hand in acknowledgement to those who had the time or the energy to greet her as she drove past. It would soon be Christmas, but there was little likelihood of much celebration in this street.

She encouraged Boney to walk a little faster than his customary plodding, but the old horse merely flicked his ears and continued to move at his own speed. Sally guided him towards the more affluent areas south of Tavistock Square. Each day she and her father took different routes, having worked out where they might miss their rival totters. Finn Kelly was the one who gave them most trouble. His family had escaped the great famine in Ireland of 1845 and Finn had arrived in London as a child of eight – that was the extent of Sally’s knowledge about his background. What she did know was that he was a rival to be reckoned with, and he used his innate Irish charm and blarney to wheedle goods out of householders where Ted might have failed miserably. Sally was determined to do better than her father, and to beat Kelly at his own game.

When the cart entered the residential area, Sally cleared her throat and sang out, ‘Any old rag and bones?’ Unfortunately her voice was drowned out by the sound of horses’ hoofs and the rumble of wheels. Hansom cabs and Hackney carriages vied with tradesmen’s vehicles and brewers’ drays. Street sellers cried their wares and they had more powerful voices than Sally, but she persevered, ringing the large hand bell that her father kept for the purpose of attracting attention.

After three hours Sally was beginning to get dispirited. The cart was less than a quarter full and it was mainly rags and sacks filled with cinders and ash from coal fires. Although these items had a small commercial value, she was not going to make more than a few pennies from the entire collection. She decided on a change of tactic and steered Boney away from the residential area, heading towards the factories that had grown up around the Regent’s Canal. She was doing a little better, having managed to persuade the owner of the knacker’s yard to give her several sacks of old bones, but when she approached the sawmill she was dismayed to see the tall figure of her archrival standing by his cart, smoking a cheroot while he chatted to the foreman.

She made a wide sweep, guiding Boney to amble in the opposite direction, but Kelly had turned his head and he had seen her. He tipped his battered top hat, and Sally was amused to see a sprig of holly and one of mistletoe tucked into the hatband. That, together with a multi-coloured striped muffler wound round his neck, gave him a raffish look, and he was grinning widely. He tossed the stub of his cigar onto the ground and stamped on it.

‘You’re too late, Sally Suggs. I beat you to it, as usual.’

Sally was about to retaliate when a small dog raced towards Boney, barking excitedly. Normally placid and slightly deaf after years of working in almost ceaseless noise, Boney reared in the shafts almost unseating Sally. The fluffy-haired mongrel seemed to think that this was a game, and continued to harass the startled horse so that the cart was in real danger of overturning. She was on her feet, struggling to keep hold of the reins in an attempt to calm Boney, when Kelly appeared at the horse’s head and seized the reins.

‘Whoa, boy. Steady, old fellow.’ Still holding the reins, Kelly bent down and scooped the dog up in one arm. ‘And you can shut up, little miss. Take on someone your own size.’