Полная версия

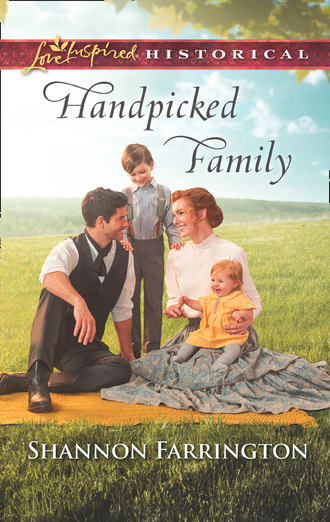

Handpicked Family

“Here, young man, this will serve as a pillow. The floor can get hard.”

The child offered him a crooked, albeit appreciative, smile. His mother, sitting beside him and cradling a small baby, looked up at Peter with a measure of surprise and thankfulness. “Bless you, sir,” she said.

Ignoring the “sir,” Peter crossed back to his makeshift desk, inadvertently casting a glance in Miss Martin’s direction. Despite his doubts about her abilities, particularly after her initial shock, she had done well organizing the people. It had made the day less confusing. After directing each person where they needed to be, she had served as a general steward, floating from station to station, serving food, washing cups and bowls, fetching bandage rolls and emptying basins.

Presently she was seated on the floor, her skirts spread out around her, tearing a piece of faded fabric into bandage strips. She was studying him, with a somewhat puzzled expression on her face, almost as if she were trying to decipher his actions.

No doubt she saw what I did with my coat. Peter offered her a look in return. One that said, No, I have not changed my mind on bringing children into this world. It had the effect he had hoped, for Miss Martin then quickly returned her attention to the bandage rolls.

He went back to his unfinished article, which he was certain would not remain unfinished for long. I have plenty to say and plenty of fire to fuel it.

He planned to work on it through the evening and then, as soon as it was light, ride to Larkinsville. From there he would wire the article back to his staff in Baltimore, and give notice of the missing supplies so that a new shipment could be arranged. Afterward he planned to have a chat with the local garrison commander. From that he hoped to discover what had happened to the Federal escorts that were supposed to protect the wagon convoy.

He settled himself at his desk and picked up his pencil. Words, however, would not come. His thoughts were in a tangle. Peter had expected his sister-in-law to be heavy on his mind, but for some reason Caroline’s image, the face he had tried so desperately to properly assemble based on his brother’s written descriptions, was hopelessly crowded out by the very real, very near and very maternal image of Miss Martin. She was now bending over the little boy he had just visited and she was kissing him good-night.

Chapter Four

Peter did finish the article, although it took much longer than he had anticipated. His thoughts didn’t clear until Miss Martin left the church building. She and Mrs. Webb went to the parsonage to gain a few hours of much needed sleep.

With the medical supervision squarely in the hands of Dr. Mackay and the night watch falling to Reverend Webb, Peter completed his article, then claimed the empty corner behind his makeshift desk. Curling up on the floor, he closed his eyes. Sleep however, came only in snatches. Thoughts of Daniel, of Caroline stole most of the night.

Daylight was just beginning to break over the Blue Ridge Mountains when Peter saddled his horse and prepared to mount. A polite greeting, however, kept him from doing so.

“Beggin’ your pardon, sir. This be the place to git some help?”

Peter blinked, trying his best to focus on the figure emerging from the darkness. It was a freedman. The man was tall and lean with clothes as ragged and ill-fitting as those of the local white men.

“Yes, this is the place for help,” Peter replied. “Go on inside and the reverend will see that you get a hot meal.”

The freedman nodded. “That’s awfully kind of ya, sir, but I was most lookin’ for the newspaperman.”

“You’ve found him.”

The man stepped closer. He removed his slouch hat and laid it across his chest. “Name’s Robert, sir—”

Peter stopped him with an upturned hand. “Enough of this ‘sir’ business. I’m no army officer. The name’s Carpenter. What can I do for you?”

Brilliant white teeth shone in a smile for a fraction of a second. Then Robert looked down and fingered his hat before saying, “I’m looking for my wife, Mr. Carpenter. She went north some years back. I been to see the bureau agent over in Larkinsville but he weren’t much help. Then I heard about you.”

Peter wondered exactly what the man had heard. He waited to learn for himself.

“Folks say that you’re puttin’ notices in your paper. That you help find people.”

“That’s true.” Or at least, that was what he was attempting to do. “If you’ll give me your information, I’ll place the notice.”

The man nodded but then hesitated. “Thing is...well, I can’t pay.”

“If you could, you’d be the first,” Peter said.

“I can work, though,” Robert said. “You need somethin’ fixed? I can do that.”

“I’m sure you can,” Peter replied. “And believe me, there is plenty to do around here. Go on inside and see the reverend. Get yourself something to eat and we will talk when I get back.”

He mounted his horse, then clicked his tongue. The old mare reluctantly lifted her hooves. Peter didn’t look back to see with his own eyes, but he knew for certain that the freedman had entered the church. He’d heard the hinges on the front door groan, and then the soft, polite greeting from inside.

Miss Martin. Knowing her, she had probably been watching from the window and came to fetch the man the moment Peter started away. He shook his head but admitted to himself that if the world was different he would be flattered by her attention. She had a comely face in a fresh, pure sort of way. She wasn’t a woman taken by powders and rouge. And she isn’t vain enough to try to hide her freckles. She’s content with the looks the Creator granted her. Peter allowed his thoughts to linger there a moment or two longer. Her eyes were green. Her hair was red, not screaming with the intensity of an out-of-control fire but warm, rich, like a slow August sunset.

His brother’s description of Caroline’s hair then came to mind. “Like Virginia soil when it is first turned...that rich reddish brown...”

His jaw inadvertently tightened. If Daniel had paid less attention to the woman standing beside that freshly turned Virginia soil and simply marched through it, Peter wouldn’t be looking for a widow and a child. Daniel had written that her father and younger brother had both died early on in the war and her mother had been taken by typhus some years before that.

Peter wondered if Caroline and her child had been able to survive the hardship of war, the sicknesses, the privations. Had she found a family elsewhere? Had she married quickly and passed Daniel’s child off as the offspring of another?

A child should know his own father, Peter thought as he broodingly plodded along. And he will if I have anything to say about it. He planned to move Caroline and the child in with his parents back in Baltimore, provide for them personally. And if she has remarried? Then he would see to it that she and the child were properly cared for and he would keep in contact to make certain it remained that way. I owe that to my brother’s child. It was hard, however, not to be discouraged. His printed notices in the local area papers concerning Daniel’s wife had generated no information. Was he only fooling himself that he could find her?

He thought then of the freedman who had approached him earlier. Am I only fooling him as well? Can I really hope to find anyone?

Peter urged the mare to hurry along, although she continued to step gingerly. Where the ground wasn’t rocky it was spongy from yesterday’s rain. It seemed a metaphor for his state of mind. Hard facts and muddy uncertainty. Such is life.

After two hours navigating roots and ruts, he saw the town of Larkinsville ahead. This tiny hamlet had fared better than the others in the surrounding area. The buildings were still standing. The telegraph office was operational. Any damage the town had suffered during the war was being quickly repaired. The smell of fresh lumber was everywhere.

I suppose the presence of a Federal garrison has something to do with that, Peter thought.

He went straight to the telegraph office to dispatch his article to Baltimore. Then he wired David Wainwright personally concerning the lost supplies. “Don’t wire yet with delivery plans,” Peter telegraphed. “More information to follow.” He knew the charitable citizens of Baltimore would act quickly to fill the present need, but it would take them several days at least to collect another shipment of supplies. In the meantime, Peter hoped to discover what had gone wrong with the first.

Having finished with the telegraph office, Peter then rode to the garrison. A scar-faced sentry forced him to dismount at the gate. After securing the mare, another Bluecoat directed him to the officer in charge, Lieutenant Glassman. The lieutenant was a fresh-faced lad who more than likely had ridden out the war in the comfort of a senior officer’s shadow, perhaps a father or uncle. He probably sheltered in a command post while other men of his age were dying in ditches.

Still, Peter did his best to cultivate a respectful relationship with the young lieutenant. Not everyone had been able to do his proper duty. He knew that better than anyone. And Glassman is, after all, the local man in charge. Animosity won’t serve me or Reverend Webb’s community well.

“Ah, Carpenter,” Glassman said as he laid aside the cigar he’d been puffing and leaned back in his desk chair. “I see you are back. Trouble?”

It was only then that Peter noticed the well-dressed man in the corner of the room. The stranger was wearing a silk vest and a brushed cutaway coat. His cravat was adorned with a jeweled pin. Peter sized up the man at once. The clothes and that superior lift of the chin told him he was either a politician or a carpetbagger. No doubt I’ll determine which in a matter of minutes.

“I hope not,” Peter said, in reference to Glassman’s remark concerning trouble.

The officer smiled, then cordially gestured toward the guest in the corner. “This is Mr. Johnson.”

Peter offered him a nod. Glassman then asked, “So what brings you to see me?”

“Questions,” Peter said.

Glassman chuckled softly. “I’d expect nothing less from a newspaperman.” He then gave Johnson a toothy grin. “Mr. Carpenter runs a nice little press up in Baltimore.”

The word “little” irked Peter, as did the shared laugh between Johnson and the lieutenant. His business here was no laughing matter, and as for his paper, he had churned out more news than many of the big Eastern papers combined. At least, real news...not war propaganda or plays on public fears.

“My question...” he said slowly, doing his best to constrain his irritation as he drew the men’s attention back to real discussion.

“Yes, yes,” Glassman said.

“I’ve come to find out what happened to the escorts that were supposed to meet the food shipment in Mount Jackson.”

Glassman blinked. “Escorts?”

“Yes. I arranged for them here in this office just last week. They did not arrive at the station, and as a result my party had to travel unaccompanied.” He then added for emphasis, “There were ladies in the party.”

“Egad!” Glassman exclaimed, looking positively chagrined. “Did they arrive safely?”

At least his concern for the ladies does him credit, Peter thought. “They did, but not without several tense moments along the road.” He explained what had happened, but he did not give any of the men’s names. The lieutenant might decide to arrest the men for unlawful assembly or worse, trying to incite a riot. Peter did not want that. Zimmer and the men of the valley had suffered enough already. What Peter did want was to know what had happened to the escorts and, more importantly, the missing supplies.

“Rebel thieves,” Johnson said sneeringly when Peter told Glassman about the lost crates.

The lieutenant held his judgment in reserve for now. “I am sorry to hear of your loss,” he said. “If you’ll see the sergeant out front, he will help you file the proper paperwork for registering complaints.”

Peter would do that, of course, if for nothing more than for the sake of proving to Glassman that he operated within the law, but he placed no faith in the army finding the missing supplies. He was certain they had already been eaten or sold. “Thank you, lieutenant, but at this point the escorts are more my priority. If,” he said, choosing purposefully to be vague, “I wire for another shipment of supplies, I must be assured of your men’s protection.”

“Of course. Of course,” Glassman said. He shuffled the stack of papers in front of him. “Date of delivery?”

“For the first shipment?”

“Yes.”

“Yesterday.”

“Yesterday?” Glassman said, eyebrows raised. “Well, that explains it.”

“Explains what, exactly?”

“The detail detachment was transferred to guard Mr. Johnson’s shipment of lumber and dry goods.” The lieutenant then added, “It was, of course, larger than yours.”

Peter could feel his anger brewing. “And that made mine less important?”

“No, not at all,” Glassman insisted, “but we are limited in numbers. We must prioritize. Mr. Johnson has important government contracts—ones which will grow the economy.”

And I am trying to feed homeless war veterans and their families. Confederate veterans. Is that the issue here? “And are his supplies for sale?” Peter asked. Although he already knew the answer.

“I’m afraid not. They have been promised to others. But if you need more supplies, you might try the stores here in Larkinsville in a day or two.”

So I may pay even higher prices for less, Peter thought, his anger rising. He cast Johnson a furtive glance, knowing he had read him right. The carpetbagger aimed to be rich, if he isn’t already.

“I do apologize for any inconvenience this has caused you,” Johnson said.

“It isn’t my inconvenience,” Peter said, “but it is a great inconvenience to the people of Forest Glade.” He turned his eyes back to the young officer. “They are under your authority, lieutenant, and they are hungry.”

“As is most of our defeated foe,” Glassman conceded. “However, it is government policy, in the spirit of late President Lincoln’s wishes, that the rebels be welcomed back into the fold. As you say, they are my responsibility. Let me know when your next shipment is due to arrive. I’ll make certain the escorts are in place.”

For now, it was all Peter could do. He’d made his point, but he wasn’t certain how helpful it would be. Glassman could promise all the assistance he wanted but he saw where the man’s heart lay—with his pocketbook. Peter wouldn’t be surprised if Johnson and the lieutenant already had some sort of deal going, but what exactly and why? Was Johnson simply paying for assured protection of his own supplies or was he actively trying to sabotage any form of competition so he may hold the monopoly and charge higher prices?

Either way people will starve. Peter however kept his disgust hidden. There was no point in playing his hand now, even if all he got out of his silence was an eventual story on government corruption.

So he thanked the lieutenant for his time, offered a conciliatory nod to Johnson. He filed his formal complaint with the sergeant, then mounted his horse and rode back to Forest Glade.

* * *

Once the dampness from the previous day’s rain had evaporated, the weather grew quite warm. Trudy didn’t think anywhere could be warmer than Baltimore City during the summertime, but evidently July in rural Virginia could be just as fierce. Even with the church windows thrown open wide, the sanctuary had been stifling. Still, she and everyone else soldiered on.

Today Trudy had collected names for Mr. Carpenter’s list in addition to washing cups, fetching clean, cool water and washing and bandaging blistered feet. Now that the evening sun was sinking toward its mountainous horizon, she paused to glance out the window. She was feeling worried in spite of herself. Mr. Carpenter had left early this morning and there was still no sign of him.

She told herself she simply wanted to share with him the information she had gathered today, that her eagerness was a desire to help the freedman who had found his way here this morning.

Robert Smith had walked into the church anxious to find his wife. She had been separated from him almost twenty years ago.

“The war is over and slavery’s done away with now,” he’d said hopefully. “I thought...well, I hoped...”

Reason told Trudy that the odds of locating his beloved Hannah after so much time were slim to none, but hope in God and a determined belief that true love conquered all compelled her to take down his information.

“Mr. Carpenter said you could use workers,” Robert had also said. “I can do almost anything with my hands.”

“I’m sure you can,” Trudy said. “Let me fetch you something to eat first, and afterward you can speak with Reverend Webb.”

The big man eagerly accepted the small allotment of cornbread and tea even though it would hardly be enough to assuage the hunger he must surely be feeling. “I’m sorry I haven’t more to give you,” she said. “We haven’t the supplies we had hoped.”

“That’s alright, miss. I’m much obliged.” He didn’t seem that eager to be left on his own, so Trudy continued to engage him in conversation.

“Have you walked a long way?” she asked.

“From South Carolina, Miss.”

So far... “And you are headed for...?”

“Not really sure yet, ma’am. Figured I stay here a while, see if I git word. If’n that’s alright.”

“Of course it is,” she said.

Sadly there were a few disapproving looks from some of the townsfolk, but no one dared to argue why a man of color was getting food. Apparently deep down they either sympathized with him or they knew it would do no good to argue supremacy to Reverend Webb. The preacher had welcomed the freedman heartily.

The two of them were now repairing the church roof. Despite the valley’s scorching by General Sheridan’s men, red cedar trees still abounded and apparently the ex-slave was an expert in crafting singles. Trudy could hear him singing while he worked.

“I looked over Jordan and what did I see... A band of angels comin’ after me, comin’ for to carry me home...”

Trudy listened to the unfamiliar but stirring words while she continued to stare toward Larkinsville, eyes straining for the first glimpse of an approaching rider. Realizing, though, she shouldn’t be lingering at the window, Trudy whispered a quick prayer for Mr. Carpenter’s safety, then turned from the glass. As she did, she nearly tripped over little Charlie.

He, his mother and his baby sister had remained here at the church because Dr. Mackay wanted to keep watch on Opal’s cough.

“See my shoes?” Charlie said, proudly showing off a pair of ankle boots, slightly scuffed but of proper size. “Mrs. Webb found ’um for me.”

“Very nice,” Trudy said, kneeling down to his level. “I suspect your toes are much more comfortable now.”

He grinned. His poor teeth were crooked and misshapen, but the smile was heartfelt and happy. “Yes, ma’am. I can wiggle ’um now.”

“Very good,” Trudy said. “Then they’ll have lots of room to grow.”

Charlie’s cheerful expression shifted to a somewhat uncertain one. “Were you lookin’ for that man?”

She could feel the heat rising to her cheeks. “Which man?” Trudy asked, hoping he wasn’t wise to her actions. After all, men had been coming and going for the last two days, gathering supplies and seeking treatment for their families.

“The one who makes the newspapers,” Charlie clarified.

Oh dear. When am I going to realize that—

“Will he be back?” he asked.

That question eased her guilt a little, knowing she wasn’t the only one anxiously awaiting Mr. Carpenter’s return. Obviously the newspaper publisher had made an impression on Charlie. No doubt giving up his soup and frock coat are part of it.

She offered the boy a smile. “Yes. Mr. Carpenter went over to Larkinsville today but he will be back.”

The uncertain expression only grew. Trudy didn’t know why until Charlie then said, “My pa went to Larkinsville to ’nlist.”

She could almost hear the rest of the sentence, though it remained unspoken...and he didn’t come back. Her heart ached for the little boy. Tenderly she stroked his dark hair. It was the color of coffee, just like her employer’s. “The war is over now, Charlie,” she said gently. “No one is enlisting anymore.”

The sound of approaching hoofbeats drew both their attention back to the window. “Well, here’s Mr. Carpenter now,” she said.

Charlie stretched to the glass, pressed his nose against the pane. “He looks hungry,” he said.

No, she thought, he looks frustrated. His visit to the Federal garrison must have been less than satisfactory.

“I’ll get him some tea!” Charlie proclaimed.

Trudy was touched by his eagerness but thought it wise to rein it in. “Let’s give Mr. Carpenter a moment to settle.” The last thing she wanted was for him to think they had been waiting by the door, eager for his return. The boy, however, waited just long enough for her employer to dismount. Then he tore away from the window.

“Charlie!” Trudy moved to catch him but it was no use. Mr. Carpenter hadn’t even time to step completely into the building before Charlie had commandeered a cup of hot tea, raced back and held it up to the man.

His left eye brow arched. He looked at the boy, then at her. A frown came over his face. Trudy’s heart withered inside, partly for Charlie’s sake, the rest for her own. Does he think I prompted the boy’s actions? That somehow I’m trying to soften up his stance on children?

He looked back at Charlie. “No, thank you,” he said.

Trudy noted the heartbreaking expression on the boy’s face as he lowered the cup. Even though she knew it would only increase Mr. Carpenter’s perturbation, she stepped in.

“I think what Mr. Carpenter means is that he appreciates your tea, Charlie, but would rather you give it to your mother instead.”

She looked back to her employer. His hard expression softened. Apparently he realized how his words had come across to the little lad. “Yes,” he said quickly as he leaned forward on his cane. “You see, I had a meal in Larkinsville. In fact...” He reached into his pocket, drew out a biscuit. “Here. I couldn’t finish this. You take it.” He then offered Charlie an awkward smile.

The boy was thrilled and quickly accepted the biscuit. With a smile of his own he tottered back to his mother. Mr. Carpenter then returned his look to her. His eyes were dark and probing. Trudy couldn’t quite decipher the emotions she saw in them but she could read a storm brewing, not one of anger necessarily, but something...

“I didn’t put him up to that,” she said bluntly.

The man blinked. Given the confused expression now on his face, Trudy decided it best to be completely forthright. “I am sorry for any inconvenience I have caused you in coming here, but I promise you my scheming days have ended.”

He drew in a breath, hesitant to acknowledge the former feelings to which she was referring. She knew, however, he understood. She could read that in his eyes.

“It’s over and done with now,” he said. “I have made my position clear. If you will accept it then we will speak no more of it.”

Accept that he never wanted a family, that he didn’t want her? She would be lying to herself to say his rejection didn’t still sting, but yes, she had accepted it. “Very well,” she said.

He offered her a curt nod in return.

Remembering Robert, Trudy then told him about the information she had taken down for the paper. “I laid it on your desk,” she said.