Полная версия

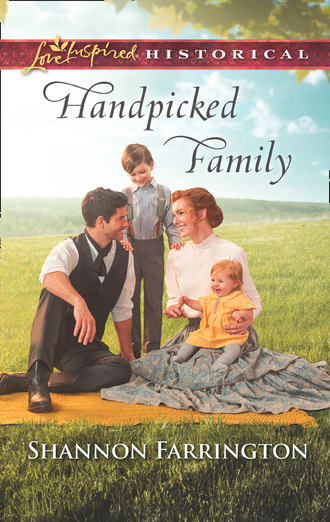

Handpicked Family

After organizing the treatment area. Trudy helped Sarah Webb sort through what remained of the dry goods and fresh vegetables. They set allotments of equal portions for each potential visitor. Sacrificially, Mrs. Webb had also raided the last of what remained of her own supplies and prepared a soup.

“I’m sorry it isn’t more,” she lamented, “but between the Confederate requisition armies and then the Yankees, this was all I could hide.”

“You must have had a secret compartment in your larder to save as much as this,” Trudy said, trying to inject a little lightheartedness into the heavy situation, “or was it the root cellar?”

“Neither,” Mrs. Webb admitted, a hint of mirth in her face. “I reburied last year’s potatoes and rutabagas in sacks in the garden.” The smile then faded. “But I’m afraid this is the end of my resourcefulness.”

“You are out of food, as well?”

“Yes. Just about. I managed to save a few of our smallest potatoes for seed this year, but the harvest was very poor. I did come across a patch of ramps the day before you came, though.”

Trudy had never heard of ramps before, except for those used in the place of stairs. “What is that?” she asked.

Mrs. Webb again smiled. “It’s like a leek. You eat the bulb.”

“Oh?”

“They are excellent in soups.”

Trudy leaned over the pot. Even as thin as the mixture was, it certainly smelled excellent.

Across the way, Mr. Carpenter had set up a desk of sorts, one made out of a piece of salvaged wood and two sawhorses. According to Reverend Webb, he had been collecting names and basic information to locate missing family members, including reconnecting former slaves with loved ones who’d been separated during the war. Apparently he planned to publish notices about the missing in his paper, and convince fellow publishers in other cities to do the same.

It was hard not to admire a man who used his press in such a way. Trudy eyed him stealthily for a moment. Mr. Carpenter’s hair was as black as coffee. He had dark eyebrows, a slight cleft in his chin and a strong, handsome jaw. He could have passed for a rich statesman were it not for the crumpled collars and askew cravats he always wore. He had a tendency to tug at them when he worked. He disliked the confinement of frock coats as well, always preferring to roll up his sleeves. He had done so today. Trudy couldn’t help but notice once again his muscular forearms.

Catching herself, she shook off such thoughts, remembering that Peter Carpenter had proven he was not the man for her. Yes, he was handsome. Yes, they shared a belief in helping others, but he was not interested in marriage. He didn’t want a family.

And he isn’t exactly a churchgoing man, she reminded herself. Oh, she knew that he believed in God, but for some reason “organized religion,” as he put it, had “no practical use.” So how exactly has he come to know and be on such good terms with the Webbs? she wondered. Had it been some connection before the war? Her curiosity getting the better of her, she asked Mrs. Webb.

“My husband, James, nursed his brother Daniel after the battle of New Market.”

“Oh,” Trudy said, her eyes inadvertently going to the still stained floor. “Mr. Carpenter has never really spoken of him.” Although Trudy knew he had a brother. She had learned that detail during the time that she, her mother and her sister had taken shelter in Mr. Carpenter’s parents’ home outside Baltimore when the city had been threatened by Confederate attack. He has two, if I remember correctly. Daniel and Matthew.

“I suppose he wouldn’t speak much of him,” the preacher’s wife said. “It must be very painful.”

“Painful?”

“Daniel survived the battle, but wound fever took him and several other Virginia soldiers a week later.”

“I see,” Trudy said. A cold chill passed through her, but her feeling was not limited to her employer’s loss alone. Trudy knew very well that fever could have just as easily taken her own brother.

Mrs. Webb must have recognized it, as well, for she looked at Trudy sympathetically. “I thank the Good Lord that he spared your own brother.”

“Indeed,” Trudy replied. “And I shall be even more grateful when he is released from prison.”

Mrs. Webb patted Trudy’s arm. “I pray for him daily, and all those like him. May God grant them the courage and grace to return to peaceful society.”

“Amen,” Trudy said.

Mrs. Webb then continued with her previous story. “James wrote a letter to your Mr. Carpenter with the terrible news that his brother had passed away. Daniel wanted it that way. I remember him saying he didn’t want his parents to learn about the death of their youngest son by letter.”

Leaving Mr. Carpenter to deliver the dreadful story. “And Matthew?” Trudy then asked. “His other brother? Did he survive?”

Sarah Webb shook her head sadly. “I’m afraid I don’t know anything about him, except that he was a Yankee.”

With that the woman walked away. Trudy resisted the urge to follow after her even if by eyes only. Mrs. Webb had been headed in the direction of Mr. Carpenter’s table. Instead Trudy picked up the nearby water pail and marched outside to the pump.

After collecting a bucketful, she took it to the fire to heat. They’d need plenty of wash water to clean and reuse the dishes once people began arriving. While waiting for it to boil, she again glanced heavenward. The sky that had previously been so threatening was beginning to brighten, but an eerie dampness lingered. Trudy remained at the fire for a few minutes more. Even though it was summer, the chill from her wet clothing had reached all the way into her bones.

Or is it my heart? She wondered. She told herself she must be careful with any display of compassion toward her employer, lest he assume she was still infatuated with him. Still, she couldn’t help but want to comfort a man she knew must be grieving.

And is he grieving for one brother or two? Trudy, along with most of her friends, had known divided loyalties. Why, her sister, Beth, had married a Boston man who’d served in the Federal army while her brother was being held in a Yankee prison. But George will gain his freedom and David and Elizabeth are blissfully happy. What had happened to Mr. Carpenter’s family? Was his brother Daniel a husband? A father? Was Matthew? Had he been killed, as well? Is that why Mr. Carpenter is so against having children of his own?

Trudy desperately wanted to know. Even though she knew it would be better for her to put the man and his troubles far from her mind. He wouldn’t appreciate sympathy or tenderness. Showing such would only further irritate him.

I must concentrate on my tasks at hand. I must be prepared. Reverend and Mrs. Webb had given all they had to help her brother in his time of need, and now their little community was facing malnutrition, disease, maybe even starvation. Trudy was determined to spend every ounce of strength she had helping them and their community in return.

Chapter Three

“It is almost one o’clock,” Dr. Mackay said as he glanced at his watch. “Our guests will be here soon.”

Peter looked up from the article he had been crafting about the need for the army to take a more serious role in protecting food shipments, just long enough to see Mrs. Mackay move to the front window. “They are already here,” she said, “and by the looks of things they have formed a line that wraps all the way around the building.”

Peter laid aside his pencil and pushed to his feet. He’d finish the piece tonight. Now was the time to be on alert. If the number of people looking for help was that large, there could be trouble.

He had already spoken to Reverend Webb about making certain the men from the road didn’t try to claim a second helping of cornmeal. The preacher agreed. As softhearted as he was, he realized better than anyone the necessity for stretching what they had to help as many people as possible.

A story from childhood scripture readings suddenly flashed through Peter’s mind, the one about how the Lord fed five thousand with only five loaves of bread and two small fish. Daniel’s favorite story. He quickly shoved the memory away. Reminiscing won’t help now.

“Before we open our doors,” Reverend Webb said, “let’s pray.”

Peter no longer believed in divine intervention, but he wouldn’t disrespect the reverend’s request. In his mind, God had created the world, then sat back and let it run unimpeded. Evil men had and would continue to have their way. The only thing a decent man could do was try to stem the tide of injustice and look after the people caught in its wake. People like Caroline and her child.

Fending off the despair that threatened to wash over him, he moved toward the center of the room, where the rest of the group had already converged, stepping up to the parson and his wife. Mrs. Webb shifted her position at the last second to make more room in the circle. Inadvertently she placed Peter between herself and Miss Martin. He saw the flush come over the young woman’s face when the reverend then requested that they all join hands.

What words the preacher actually prayed Peter couldn’t say. He was much too conscious of the slenderness and softness of Miss Martin’s fingers, testaments again of her sheltered life. She had no idea what heartbreak was waiting for her outside.

She will soon find out. Not that he wished to deliberately hurt her, but someone needed to educate her on the realities of the world today. Peace had been declared and the reconstruction of the Union had begun, but the people outside had been impoverished by their own country. Of the Confederate veterans who had managed to return, few were able-bodied. Arriving home, they found their lands in ruins, and no longer their own, for they had been confiscated by the Federal government.

The only thing taking root around here is the seed of resentment. What will they do if they are given the opportunity to avenge themselves? An angry man may be all too willing to lash out at anyone he can find—even someone as harmless and well-intentioned as Miss Martin.

Of course, not every man out there was a danger or a threat. Many were well-intentioned themselves, simply seeking a way to get on with their lives, but lacking the resources to move forward. The slaves were free, but the freedmen Peter had talked to had been told by Federal authorities to remain on the plantations, let their masters feed and clothe them until the end of this year. What kind of freedom is that? Their masters have no food to give them. The slaves had been promised forty acres and a mule of their own. Taking their chances, many were migrating north, seeking work in any form, desperate to be reunited with loved ones.

Peter couldn’t help but then think of the ordinary family farms, and the people on them who had simply disappeared. Who will gain their land? In time enormous profit will be made from these derelict farms, but it isn’t going to be claimed by the ones who had once labored on them.

The world was a cheap mess. Someone was going to profit, of that Peter was certain. Someone always did.

His lame leg was aching. It always bothered him when the weather was damp or he had stood on it for too long. He would have to remember to use his cane. Presently, though, he couldn’t remember where he had left it. He shifted his weight just as the reverend offered prayers for the regional garrison commander.

“Bless him, Lord. Give him the wisdom to look after those in his care...”

Peter couldn’t help but think that that request, if heard at all, would be better presented on behalf of Reverend Webb himself. In Peter’s time here, no leadership, save one overworked preacher trying to shepherd what remained of his refugee flock and protect it from encircling wolves, was doing anything to help.

But for so many, there is nothing to be done. Too many men had gone into battle never to return. Reverend Webb had told him there were at least a dozen surnames in this community that were destined to die out upon the widow’s death. Either her sons had perished, leaving her childless, or daughters alone would struggle to carry on a father’s legacy.

As for the children Peter had come upon, some weren’t even old enough to attend school, meaning they had been born since the start of the war. What had those men been thinking, fathering children while knowing hostilities were on the horizon? Deep down he knew he shouldn’t be angry with Daniel, let alone his brother Matthew, for being among them, but he couldn’t help it.

Inadvertently, he cast a glance at Miss Martin. Her head was bowed. Her feathery auburn eyelashes rested against her creamy skin. She was the picture of youthful innocence. The sooner she learns that romance breeds nothing but trouble, the better off she will be.

Peter released her hand the moment Reverend Webb pronounced his amen. He turned at once, bound for the front door. The preacher had already asked him to greet and give those outside their instructions. Dr. Mackay, however, stopped him.

“Take Miss Martin with you,” he said. “She can assess their medical conditions, then direct patients to either me or Emily.” He turned to her before Peter had a chance to object. “Remember, no typhus or smallpox inside the church building.”

“Yes, sir,” she said.

Peter drew in a deep breath. He knew the effects of those two epidemics and didn’t like the idea of Miss Martin being the doctor’s first line of defense.

“Perhaps you should do the assessing, Doctor,” he said.

This time Miss Martin took immediate offense. “I’ve dealt with infectious diseases before,” she said before Mackay could speak.

“Indeed,” the doctor then said. He looked back at Peter. “And I’ve not time to explain to you how to assess patients.” He went on to deliver instructions to his brave little nurse. “Make them aware of our stations and send any with acute needs to me, the lesser ones to Emily. You know what to look for. Just like our days in the hospital.”

“Yes, of course.”

He then handed her several sheets of paper and a pen. “Take down their names, and the location and number in their household if they will divulge such information. It will be helpful to know for future ventures.”

“Certainly.”

Clearly the matter had been firmly decided. Peter wanted to press that point, but Miss Martin was already headed for the door.

* * *

The chill Trudy had felt previously evaporated the moment Mr. Carpenter had taken hold of her hand. She scolded herself for such a reaction, even though it was only a fleeting feeling. The moment Reverend Webb pronounced the amen, Mr. Carpenter gave her a look as if to tell her he thought the whole arrangement of the circle had been her idea. He then gave Dr. Mackay an almost icy stare when the physician suggested she accompany him outside.

He clearly does not want me here. Evidently he thinks I am unsuited for the task.

Trudy blew out a breath. Determined to prove him wrong, she marched to the front door before her employer could say or do anything else. Stepping outside, however, she gasped. Emily had been correct in saying that line wrapped all the way around the church building. It wasn’t the number of people, though, that disturbed Trudy. It was their condition. They were even more desperately downtrodden than the men on the road. Most of them were young women and children. The women were presumably now widows because no man was beside them, and by the looks of them, no man has taken care of them for quite some time.

The woman at the head of the line was so thin, so frail in appearance that Trudy wondered how she had remained standing. In her arms she carried a small baby. A little dark-haired boy, five or six years old, was standing beside her. The boy was wearing shoes but his clothing was tattered and full of holes. Through one particular spot Trudy could view his ribs.

Is this Charlie and baby Kate? Trudy wondered. Is this the family of which Reverend Webb spoke?

Her heart broke afresh, for there were many others just like them. Looking upon them, her confidence faltered. She had tended frail and malnourished bodies before, but this was quite different! These women and children hadn’t volunteered for the cause, yet they had been forced to suffer its cost. The reverend said there would be children, but somehow I suppose I was still expecting soldiers. I had no idea it would be like this!

Grief washed over her in waves and she could feel the tears gathering in her eyes. She was so overwhelmed that she didn’t know where to start.

“Hold firm, Miss Martin,” Mr. Carpenter commanded behind her, but in a voice only she could hear. “These are proud people. They need your assistance, not your pity.”

Knowing he was right, and determined to prove she could handle what was expected of her, Trudy drew in a deep breath, steeled her resolve. Just as she moved to descend the porch steps, he caught her arm.

“Let me go first,” he said.

“But I must assess—”

“What are the most prominent symptoms of typhus?”

Feeling her own irritation growing, she spouted off the list. “Severe headache, high fever, sensitivity to light, rash on chest and back...although if they have that, they probably won’t be standing.”

He nodded. “And smallpox?”

“Much the same, but the red spots will first appear on the face.”

“That’s what I thought,” he said. “Now, give me your list. I’ll take down their names and assess for those diseases.”

“But—”

“Don’t argue with me. Go see to that little boy right there. He looks well enough.”

He didn’t wait for her to respond. He simply took the pen and paper from her. Then he announced to those gathered who they were and what they were about to do.

Trudy knew full well she should not waste time feeling angry over his forceful, take-charge behavior, but she couldn’t help herself. Yes, I faltered for a few seconds, but I am fully capable of discharging my duties. Then the idea struck her, Is he trying to protect me?

Shaking off the thought before her mind could go further with it, she moved to the first mother and children in line. She offered her best smile. “My name is Miss Trudy,” she said, bending toward the boy. “What is your name?”

“Charles T. Jackson,” he said proudly. “The T is for Thomas, but Ma just calls me Charlie.” He gestured to the woman beside him. “This is Ma...and Kate.”

Trudy looked then to the woman who said that her name was Opal. Apparently she and the children had walked six miles this morning to come to the church. The distance had taken its toll on Opal’s feet. She was wearing makeshift shoes, a slice of hickory bark for each sole, secured by strips of cloth to her ankles. Her stockings, having been darned many times, were now threadbare. Trudy could tell her feet were bruised and blistered. Emily would need to tend them.

“If you’ll go just inside and see Mrs. Mackay,” she told Opal. “She’s the one with the white apron. She’ll see to your feet. Mrs. Webb will bring you some soup and I’ll see if I can’t find a pair of shoes for you.”

“Not me,” Opal said, “but for Charlie. His shoes are much too small.”

Trudy had seen the effects ill-fitting footwear had on the infantry, and if this boy had similar injuries... She pushed the thought away and smiled again at Charlie. “Better let Mrs. Mackay take a peek at your toes, too.”

He nodded obediently, but then his attention was stolen by Mr. Carpenter, who was working his way up from the line. Trudy’s was, as well.

“No smallpox or typhus,” he whispered as he bent his head toward her ear.

Trudy breathed a sigh of relief, then watched as Mr. Carpenter turned and started working his way back down the line. He was leaning heavily on his good leg. She knew his other must be hurting. Presently Mr. Carpenter was taking names and asking questions concerning the local authorities and the missing food.

“That lieutenant over there at the garrison don’t concern himself with our matters,” Trudy heard one man tell him.

“Wouldn’t want no help from him even if he was,” another said.

“That man a Yankee?” Charlie asked her, his eyes apparently still focused on Mr. Carpenter. Trudy quickly turned her attention back to the boy. She wasn’t certain of the best way to answer his question, given what had happened on the road. “He’s not a soldier,” she said. “He’s a newspaperman. He is trying to find fathers and brothers who are missing.”

“Oh,” Charlie said. “I wanna be a newspaperman when I git big.”

At that, Trudy couldn’t help but smile. She gave the boy’s dark hair a loving tousle, then moved to the next family in line.

Blisters and minor skin infections were common sights, but there were plenty of coughs, bleeding gums and bruising, as well. The people’s lack of nourishment was manifesting itself in ways beyond thin faces and prominent ribs. Despite the blessed lack of a potential epidemic, her hope was low by the time she reached the end of the line.

A few sacks of cornmeal and Mrs. Webb’s soup, generous as it was, aren’t going to stem the tide. These people need meat and a regular diet of good nutrition, but she knew full well there wasn’t a chicken to be found in all of Virginia, and as for fresh vegetables, there were few now to offer. Still, faith compelled her to remain positive.

If God by his grace will sustain them a few more weeks, Dr. Mackay will send for more seed, more food, more medical supplies. We just have to do the best we can until they arrive.

Lifting her skirt, Trudy marched up the porch steps, intent on helping Sarah Webb distribute the soup and rations. It did not take long. When the last of those in need had been fed, Mrs. Webb offered her and the others a cup. Trudy was most grateful for the meager meal, as were her friends. They eagerly ate what was given—all, that is, except one of them. Mr. Carpenter had accepted his portion, although Trudy noticed he discreetly gave his cup to little Charlie when he thought no one was looking.

* * *

By the time darkness had fallen, most of the people had been tended. Miss Martin had efficiently assessed and directed those in need. Peter was relieved. There had been no trouble, socially speaking—no attempt by Zimmer, O’Neil or Jones to collect more food than allotted to them. Reverend Webb had insisted Zimmer was a bit of a bully but not one of serious action. Blustering was about all he would do.

What man with a hungry family in these conditions wouldn’t do the same? he thought. As for Zimmer’s family, Peter had not met them. The distance across the mountain was too far for them to travel and, apparently having no pressing medical needs, they had remained at home. Peter would have liked to have spoken to Zimmer’s wife, but he had through his conversations today learned one important detail. Mrs. Zimmer’s name was not Caroline. Unfortunately, Peter hadn’t met any other Carolines today and no one he had talked to had ever heard of anyone by the surname Carpenter.

His leg was aching and his belly rumbling. Peter found a quiet spot in the corner of the room and sat down. The most serious medical cases, coughs and reinfected wounds, remained. Those patients were destined to sleep on the floor or pews softened by what blankets Mrs. Webb could spare. He glanced about. The place looked as pitiful as any wartime field hospital, except the majority of those in distress were not soldiers. They were women and children.

Two of the widows in relatively good health had remained for the night rather than risk walking home in the dark with their small children. Peter wondered if the real incentive wasn’t the opportunity to share in the church’s store of lamp oil and the hope that the reverend’s wife might produce more food come morning. If that was the case, he couldn’t blame them. Remembering his frock coat on the back of his chair, he picked it up, rolled it into a ball and gave it to a particular dark-haired little boy. He had seen the child eyeing him a time or two today. Earlier he had given him his cup of soup because he knew that more than likely, the boy was still hungry after eating his own share.