Полная версия

The Heart Beats in Secret

Copyright

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © Katie Munnik 2019

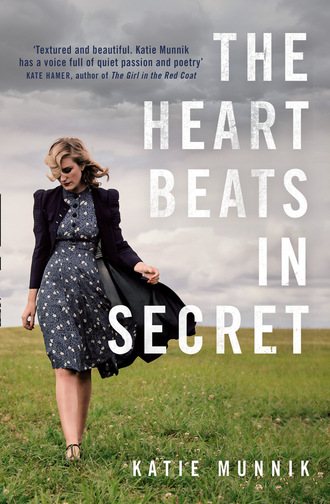

Cover photographs © Elizabeth Ansley / Trevillions Images

Cover design by Ellie Game © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Katie Munnik asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

Excerpt from The Trail Of The Lonesome Pine Words and Music by Harry Carroll and Ballard MacDonald © 1927 Shapiro Bernstein & Co Inc Shapiro Bernstein & Co Limited, New York, NY 10022-5718, USA

Reproduced by permission of Faber Music Ltd All Rights Reserved.

Excerpt from Basho, translated by Lucien Stryk, Penguin 1985

Excerpt from A Doctor Discusses Pregnancy, William G. Birch, Budlong Press 1963

Excerpt from Everybody’s Pudding Book, by Georgiana Hill, Richard Bentley 1862

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008288082

Ebook Edition © April 2019 ISBN: 9780008288068

Version: 2019-12-19

Praise for The Heart Beats in Secret:

‘Textured and beautiful. Katie Munnik has a voice full of quiet passion and poetry’

Kate Hamer

‘Munnik unfurls her story in quiet, reflective prose, but there is much to enjoy along the way’

Town and Country

‘[A] powerful, multi-generational novel … full of secrets, stories and discoveries’

Prima

‘Beautifully written and moving’

Woman’s Own

‘The Heart Beats in Secret is a spacious and yet densely woven work … beautifully written’

The Cardiff Review

Dedication

For Mike, of course.

Epigraph

What are heavy? Sea-sand and sorrow:

What are brief? To-day and to-morrow:

What are frail? Spring blossoms and youth:

What are deep? The ocean and truth.

Christina Georgina Rossetti

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise for The Heart Beats in Secret

Dedication

Epigraph

Part One

Chapter 1: Pidge: 2006

Chapter 2: Felicity: 1967

Chapter 3: Pidge: 2006

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6: Felicity: 1967

Chapter 7: Pidge: 2006

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10: Felicity: 1968

Chapter 11: Pidge: 2006

Chapter 12

Part Two

Chapter 1: Jane: 1940

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Part Three

Chapter 1: Felicity: 1969

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Close: Pidge

Jane: 2006

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Katie Munnik

About the Publisher

For Columba Livia,

to be delivered after I am dead

Well, my dear, the house is yours. Regardless of what your mother might expect, I think it only makes sense. She wouldn’t really want it anyway. All the way out here on the other side of the world, isn’t it? Perhaps she might like to sell it and use the money, though I’m not sure that’s necessary. She seems comfortable where she is. And she’s never been one to look for windfalls or godsends. But maybe you could use a few, so I’m leaving it to you.

It’s a good old house. Friendly in its way. I’ve been happy here. Don’t worry, I wouldn’t be offended if you sell it, and I won’t haunt you. I promise. But before you decide anything, do come and see the old place. You haven’t been out here since you were a child, and it may feel different to you now. So come and stay for a while. Long enough to get a handful of warm days – we do get them here, you know, the kind when you open the windows in the morning and leave them open all day, forgetting about them until the curtains blow in just before sunset, when the wind shifts. I have never figured out why it does that. I always meant to ask someone, but never got around to it. Does it happen elsewhere? Or is it only here in this house? Maybe you know, my dear Pidge. Does anyone call you that any more? I must say, when I was drawing up the official paperwork, I had to be so careful with the spelling of your real name. Your mother was right – it has a lovely ring to it. But I was right, too, wasn’t I? It is a strange name to saddle any child with. Yet you, my dear, wear it well. Felicity said that the other mothers wanted to use old-fashioned names, like the ones their grandmothers wore – Jean, Rosa, Edith. Or natural-sounding names like Oak and Ivy, which are only apt out there in the woods. But she wanted something distinctive for you. Oh, your grandfather laughed! It is a beautiful name, even a little fancy in the best way, though pigeons are just as common as the rest of us. But perhaps no one knows Latin these days so that doesn’t matter. I hope you haven’t found it a burden. We all burden our children, I suppose. One way or another.

I hope this house won’t be a burden for you. It’s only a house. Or a bit of money, if you want it that way instead. You would need to clear things out first, so that’s another reason to visit. There may be a few things here you would like to keep. Books or photos, or sentimental odds and ends. It is all fairly old, but it has been useful. Useful or lovely.

When you come, you can take the car out, too. I’ve left that to you as well, though there’s a man in the village who would be happy to buy it. Just ask at the hotel and Muriel will point you in the right direction. She’ll also have a set of house keys for you, if there’s any trouble getting them from the lawyer. You’ll know her when you see her. I thought it best to provide local solutions so you don’t need to go into the city unless you’d like to. There’s more than enough to see around here. Drive out along the coast. Go see some ruins. Or the old doo’cots. There’s a man named Izaak who lives near here. A few years ago, he put together a calendar with drawings of all the local doo’cots. Beehives and lecterns and all that. He’s clever at shading and really captures the way light touches old stone. There should be a copy of it somewhere around the house. Maybe in the bookcase. I can’t quite remember.

Anyway, be well, my dear. Be happy. Live where you like, but when you’re here, do take some flowers to the kirkyard and think of me a little. And if you stay until they are ripe, be sure to eat all the brambles you can find.

With all my love,

Gran

1

PIDGE: 2006

LONDON AND BREAKFAST AT THE AIRPORT. JUST COFFEE and a scone – a crumbled thing that tasted of margarine, and the coffee was too hot so I drank it down quickly. It was only fuel. Mateo had arranged the rental car for me. He likes to do that sort of thing. Said that if he couldn’t be there, he could at least help with the details. So he bought me a guidebook about local history. He planned out my route and bookmarked the maps. And he’d arranged the car. I could pick it up at the airport, then drive north to Edinburgh. I could have flown, but it was cheaper to drive. Mateo said I was crazy – these Canadians and their long distances – but really, I wanted the space. And the effort. I didn’t want to be delivered to my grandmother’s empty house like a package. I wanted to make a journey of it. So I’d drive straight through, listen to the radio, watch the weather. Then a hotel room for the night and a bus in the morning to Aberlady. Mateo had written all the details on a bit of paper that I slipped into my passport, and he also sent it all by email so I’d have everything in one place, if worse came to worse.

‘Worst,’ I said.

‘What?’

‘Nothing. But you mean if I lose the paper.’

‘Well, yes.’

‘I’ll be fine, love.’

‘Of course. I just want you to be looked after.’

‘Thank you.’

After a pause, he asked me if I knew why.

‘Why?’

‘Yes. Why she left you the house. Why not your mother?’

We were sitting together upstairs in the gallery, side by side like an old couple, looking down into the garden courtyard. I’d hoped that we could have lunch – our last day at work together before I flew – but he had a meeting booked, so we just managed a quick chat in the middle of the morning. Bright sunlight fell in through the windows overhead, and the pale stone walls hushed the space like snow in a clearing. Everything was glass and granite, which suits Ottawa well. Like ice, snow and bedrock.

‘Maybe she thought I’d like it,’ I said. ‘I might. Like it, I mean. You might like it, too. It’s a good house.’

At one end of the courtyard, volunteers were setting out materials for a children’s craft session – lots of coloured paper set on bright foam mats.

‘You mean to vacation there? I am not sure about that.’

‘There’s a beach.’

‘Not a real beach. Too cold for that, no?’

‘Maybe, but it’s lovely. With sand and everything. I used to swim there when I was a child.’

‘Under a frozen sun.’ He smiled and took my hand in his. He had beautiful Spanish hands, soft and perfect. Gentle. I tried to smile, too.

When I first knew Mateo, we used to meet here often. I’d pick up the phone when the shop was quiet and I could slip away and he’d leave his office or the archive to grab a moment together. We’d just sit. Maybe hold hands. I think neither of us could quite believe our luck. You don’t stumble on love like this, do you? Just open your eyes one day at work and there it is. That doesn’t happen. Except it does.

‘I suppose I might sell it,’ I said. ‘A bit more money for the condo. Maybe we could afford a little more that way.’

‘Yes, maybe. But there is another question. Did she give it to you or leave it to you?’

‘What’s the difference? She just wrote that the house was mine.’

‘Money is the difference. Inheritance tax. But I am sorry to be talking about money when you are grieving. None of this matters. I only wondered. And wondered about your mother, as well.’

The volunteers were laughing now, their voices brittle at this distance, their hair shining in the falling light. Mateo sat with me for as long as he could, still holding my fingers in his beautiful hands. After he left, I took my usual route back through the European rooms to visit the Klimt. I like her. Her face doesn’t change. In the shop, I sell a lot of postcards; so many people want to take her home. I want to ask them why. I wonder who they see in her eyes.

I pulled off the highway at a service station, a place where everything looked plastic and you could buy pre-wrapped muffins and coffee in cups to take away, or choose to sit at small tables and eat plates of fried eggs, ham and chips. I bought a boxed sandwich, a coffee and a chocolate bar I didn’t want and ate in the car.

Over the border into Scotland, the highway narrowed, the landscape rising on either side, and the traffic thinning away. I expected rain. Or sheep. Or both. Everything was green – so much greener than home – and the April sun was warm through the windshield. Then before Edinburgh, I saw a sign for Birthwood. The sudden scent of home: cedar, wild garlic, pennyroyal and pine. I glanced away and back again, but there it was. I hadn’t misread. Birthwood. She never told me it was an old name. A real name. It felt odd seeing it on an official sign. I wanted to stop and take a photo or turn off the highway to see – but to what end? Nostalgia. Suspicion. Romance. I kept going, driving north-east.

No more service stations now, just small villages with bakeries and convenience stores, low white houses with heavy black lintels, old stone walls. A few trees and, beyond them, fields that stretched out to the greening hills, then cloud-hills clustered up, grey against a grey sky. I turned the car radio on and off again. Birthwood must be a small place. There had been no sign of it on the map. A crossroads, then, or the name of a farm. Insignificant but for the fact that Felicity had never told me about it.

This stretch of highway ran along an old Roman road. That had been on the map. Ancient history in ten miles to an inch.

When I was a child, the woods at home were timeless. Bas taught me people had passed among the trees for centuries, following the seasons and animals, coming and going and coming again. Others arrived from further away – traders, priests and settlers. For a while, they tried to stay, then moved on and built cities elsewhere. The forest returned and thickened, but Bas could still find their traces. He showed me wheel ruts and weathered split-rail fences that divided up the now-indifferent bush, crumbled houses and broken barns kneeling like fallen dinosaurs or other long-forgotten beasts stumbling towards extinction. The built history of people didn’t last long. A couple of centuries at most. The trees themselves might almost remember.

Out here on the highway and beneath these bare hills, time felt different. Stretched and snapped. The Ninth Legion marched away at the end of my mother’s childhood. Tacitus scribbled notes in my grandmother’s living room. In the space between the Roman roads and the plastic sandwiches, you could lose your balance.

I could see why my mother left.

But that’s not fair. It would be different if you were born here. This is one of the places where my mother was born. Not quite here, but down this road, anyway.

She used to count out her births for me. The first happened so early she couldn’t remember it and she’d say that to make me laugh. Then she’d tell me about her mother’s labour, her grandmother’s flat, about her father who was a soldier and couldn’t be there.

The second was a beautiful picture – light after rain, pavements shining and the clatter of pigeons lifting from the rooftops to wheel over the city, out towards the sea. She was young and everything was starting. She told me this story after thunderstorms or when I couldn’t sleep. She stroked my hair, then whispered French rhymes in my ear.

There was a third story, too, but she wasn’t good at telling it. She’d polish it and change it after arguments or when she was worried. I sat on our cabin’s doorstep and watched the wind ripple the surface of the lake as she wondered aloud about the things we get to keep, the things we release and the way we might, if we’re lucky, get to choose.

2

FELICITY: 1967

I LIED MY WAY INTO AN INTERVIEW. THAT’S WHERE IT started. I hadn’t meant to, but what with the rain, my wet shoes and Dr Ballater that February, it happened. I wouldn’t have planned it. I didn’t have the nerve.

When I worked for Dr Ballater, I was docile. Polite. He came into my high school looking for a sensible girl to help with the surgery’s desk work. Just for a few weeks before Christmas, he said. Miss Jones suggested I would be suitable and summoned me to meet the doctor in her office. He stood quite close to the door so when I stepped into the room, I saw him immediately. I don’t think he meant to startle me; he just wanted to see how I might react. So, I didn’t. Or rather, I politely said hello, shook his hand and sat down in the chair Miss Jones offered. Dr Ballater spoke in a soft voice, describing the work and the practice, meeting my gaze directly as he did so. I folded my hands in my lap and nodded.

Before the war, he may have been handsome, but now it was hard to tell. He had what can only be described as a splodge of a face. I suppose that’s not kind, but I’m not sure how else to describe it. A puckered welt ran from above his left eyebrow, across his misshapen nose, and down to his chin. The skin around the wound looked raw and mottled. He didn’t make me nervous – there were plenty of injured men around when I was growing up. Still I kept noticing how his skin pulled as he spoke and how each expression dragged on long after his words. It was difficult to act naturally. He seemed a kind and tired man.

I thought he was my father’s age, and maybe he was. He said that when the war started he had only recently qualified. Like so many young men, he’d been persuaded by the call to arms.

‘I assumed I would be given ambulance duty,’ he said. ‘Like the writers in the Great War. Instead, they planted me in a field hospital as a surgeon. That didn’t last long. A bomb fell on us and they sent me home.’

He told me that on my first day. I guess he wanted to get it out in the open. After that, he never spoke about the war, nor did he speak about his return home, so I needed to fashion that part of the story myself. A long convalescence in a grand manor house somewhere in the west of Edinburgh. Daffodils on the lawn. Starched sheets and painkillers. I imagined a nurse with gentle hands. Soft eyes meeting his. And tragedy, too. There must have been tragedy because I knew he lived alone. That part of the story needed work. Maybe she was married; maybe she had died. Influenza perhaps, but that didn’t strike me as wonderfully romantic. Maybe she’d been caught in an air raid. London then, I supposed, but maybe Edinburgh. Mum had told me about the planes over Marchmont on the night I was born. Maybe Dr Ballater’s sweetheart was killed that night. How strange to imagine.

This was how I passed afternoons at the surgery, keeping an eye on the mantel clock, and half dreaming out of the window. At quarter past four, Dr Ballater liked a pot of tea brought through to his desk. At first, that was my least favourite part of the day. The kitchen always smelled like bleach, and the bamboo tray felt too light to be sturdy. I balanced my way along the short hallway from the kitchen, and Dr Ballater opened the door just as I arrived. I hated knowing that he stood waiting for me, listening to my steps. That face behind the door. It was better when he walked back towards his desk and cleared a space for the tray. He opened a drawer and removed an elaborately embroidered tea cosy. The lost love must have made it for him, of that I was sure. He set it on the teapot with such precision and told me he was happy to have me. My typing was good, and the patients thought I was friendly.

He started asking me to join him in the afternoons. ‘Just a wee blether and a cup of tea, wouldn’t that be nice?’

He told me about his childhood in the countryside, not far from Biggar, about the hills there and the clear sky at night. He asked me how I liked school, about my parents and how they were feeling. Once he asked me what my plans might be for after school and I waffled nervously. I really hadn’t thought that far, not in detail at least. I imagined a flat somewhere. Maybe over in Glasgow, though Edinburgh might be more practical. I would be chipping in with other girls, of course. Cooking small meals over a hotplate, sharing adventures. The previous Christmas, I’d worked the January sales in Patrick Thomson’s, and one of the other temporary girls talked on about her bedsit, which sounded exciting. I could imagine that. But just what I’d be doing there, I hadn’t a clue. That wasn’t an answer to Dr Ballater’s question. So, I said I was looking into university and might read geology. It didn’t sound unreasonable as I said it.

He suggested that nursing might be a better fit.

‘It’s a good life and there are always those that need helping.’

In the end, that’s what I did. Signed up for the new degree programme at Edinburgh University and found a flat-share which was cold and nowhere near as romantic as I’d hoped. We all worked hard and stayed over in the hospital when we could, to keep warm. Sometimes, we went for coffee or to the films, and on Saturday evenings we were welcome to join the boys at the student union for the weekly dance.

The spring I graduated, one of the medical students invited me to the May Ball and I cut my hair like Sylvie Vartan, bobbed and fringed. I barely knew him and we danced until they turned the lights on. Was that polite? I suppose it was. Then he walked me home to my student digs in Marchmont, a long beautiful saunter along Coronation Walk. The cherry blossom was thick overhead and underfoot – blossom soup, blossom salad – and the night was so clear and almost bewitching, but he was certainly polite and I wished he wasn’t. I climbed the stairs alone and felt a little guilty for my loneliness as I fell asleep. In the morning, I caught a train home to East Lothian to see my parents, the sea and the sky dirt-pearl grey.

There was a job waiting for me with Dr Ballater. That worked out rather well. My parents were happy to have me home again, and we all knew that it wouldn’t be a permanent arrangement, but in the meantime, I could save up for a car. I banked my money in an empty margarine tub on the shelf next to my alarm clock.

For the next five years, I worked for Dr Ballater. Each year, I weighed and measured all the schoolchildren, and inspected their scalps. I bought that car and established a rota of housebound widows who might benefit from a visiting nurse. In the autumn, I helped with the kirk jumble sale. In the spring, it was the Easter tea. Mum couldn’t be bothered with all the village business, as she called it. She was far happier pruning the trees in her orchard or foraging about in the hedgerows. Sometimes, she would have the minister’s wife round for a cup of tea or Muriel would come up from Drem, but mostly, she and Dad lived quietly and left the social affairs to me. I found I liked it when the village ladies dropped by the surgery with invitations and requests for assistance. It kept me busy and helpful. Cheerful, as befits.