Полная версия

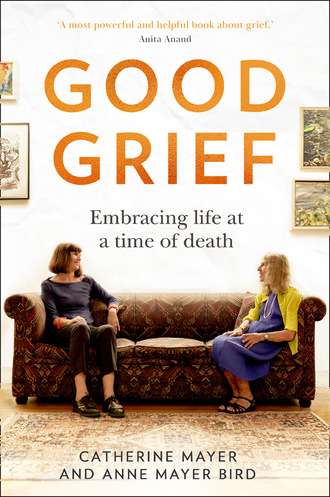

Good Grief

Listening to this recording, I yearned to interrupt Andy, to add a missing element of exposition: the waiter offered to bring the menu back because the dish I’d ordered had run out. And, by the way, his name was Simon. That’s how long-term couples often communicate, speaking across each other, issuing small additions and clarifications to their joint narrative. My mother and John were like that too. If you didn’t know how much they loved each other, you might have thought they were bickering. ‘Oh Anne,’ John would say, rolling his eyes. ‘Which of us is telling this story?’

A sadness in writing this book has been the absence of that affectionate, jousting dialogue, though my mother and I fall into similar habits when we meet in her living room. Are you sure that’s right, we ask each other? Didn’t that event precede this one? In search of answers, I pore over old text messages and WhatsApps, emails and my online diary. There are other resources too, including Andy’s mobile and computer, but I’m inexplicably reluctant to switch them on and startled by the volume of correspondence when I do. Friends and strangers still send him messages to tell him how much he meant to them. Until his number was disconnected, there were voicemails. ‘Andy, I miss you. I wish I had seen you more often. You’ve shaped my life more than you’ll ever know.’

Needs must. I force myself to fire up his computer, look through the calendar on his phone. If only he and John could give you their version of events – and correct my mother’s and mine. In the Sunday Times recording, Andy identifies me as an unreliable narrator. ‘Memory’s a funny thing, isn’t it,’ he says. ‘I actually think she gets things wrong when she’s looking back at certain events and I’m going “no that’s not quite how it happened.”’

My mother and I from the outset resolved in telling our stories to stick to the truth as closely as we could, even where it is painful or uncomfortable. My amnesia complicates the process and distresses me for other reasons too. Days have disappeared, but these were anyway disposable, post-Andy days. It is the sense of our life together slipping out of reach that torments me, his scent (I keep an unwashed t-shirt in a Ziploc bag, but it smells more of hospital than Andy), his stories. I drive myself mad, or madder, trying to remember his stories. There’s one he used to tell about his youth involving a mix-up between Tony, a hash-dealing acquaintance, and the dealer’s father, an upstanding, pillar-of-the-community also called Tony. The anecdote always made me laugh. Now I retrieve only fragments: Tony Senior answering the phone to a client of Tony Junior, who requests ‘a pony’ (£25’s-worth) of Junior’s wares; a punchline ending with the Lady Bracknellesque exclamation ‘a gymkhana?!’ Was this tale inherently funny or did the humour, as so often the case, rely on Andy’s delivery?

I remember the name of a waiter from three decades ago. How is it that other small details elude me? These turn out to matter at least as much as the big stuff. Yes, yes, so Andy was an extraordinary guitarist, a ground-breaking musician, something of a genius. Right now, my dearest wish is to find him in the studio, disturb him even if he’s writing another trailblazing work, make him tell me, one last time, the story of Tony’s dad.

That last Christmas dinner, he told no stories. He was quiet, abstracted. My attention was on my mother. My sisters and I had already begun to discuss with her what practical support we could offer. Catherine A would work with Cassie on the estate and with me on organising the funeral; Lise would handle the wake. On 27 December, I paid a visit to A. France & Son, the funeral director in Lamb’s Conduit Street that three years earlier had handled the ceremony for Sara B, under instruction from me and her children. On 6 February, I would return to A. France for a third time to ask them to organise a cremation for Andy. I should have requested a bulk discount.

Death is monstrous. Sometimes it is funny in a monstrous kind of way. The fates that conspired to snatch John and Andy, then impose a nationwide lockdown amid a global pandemic, were having a right old laugh.

Chapter 2: Denial

‘I always knew I would lose you, but I never told you of my fears; of the night, six months into our relationship, when you curled up to me, your skin so smooth. When I reached for the light, I spotted a lesion on the nape of your neck, black as the future, obviously a melanoma. I loved you too much to deprive you of a last untroubled sleep, so said nothing, hit the switch and lay awake beside you for hours, dreading the dawn and what lay beyond that dawn. Such a strange thing: I wasn’t neurotic. You can testify to that. I took risks with my own life. I still do. Yours seemed more fragile, even then. Of course, when I looked again, at first light, I could see that the mark was not a mole, but a piece of wax paper, the corner of a Mars wrapper. You always did like to eat chocolate in bed.’

I wrote these words in August 2019, part of a novel that now will never be published and probably never deserved to be. In my reimagining of H. G. Wells’ The Time Machine, the Time Traveller – a Silicon Valley tycoon – tricks the Narrator into accompanying him to a future shaped by a global pandemic. The Time Traveller deploys his technology in a self-aggrandising mission to tackle problems created by technology. The Narrator sees another possibility: she might bend time to save her partner of many years, who is dying.

When I embarked on the novel, months ahead of the first reports of an outbreak in Wuhan, the pandemic and its impact were fiction, my descriptions of the melanoma-that-wasn’t and the partner who ate chocolate in bed, autobiography. The Narrator spoke in my voice and of my deepest terrors.

I suppose that in articulating these terrors, I hoped to stop them from materialising. Yet something else also compelled me to write – the absence of any other outlet. Andy was my closest companion. Our working lives could be demanding, but we always made time to talk. We wrote in adjacent rooms, cooked together, ate together, spent evenings lounging together, with friends or just the two of us. We agreed to leave serious discussions for daylight hours and our weekend walks. As we strolled, nothing was off bounds – nothing except the most serious topic of all. He would always shut down conversations that reminded him we couldn’t live, as we were, forever.

‘Rock musicians have shorter lives than other people.’ This is the bald observation of an academic paper published in the scientific journal Advances in Gerontology and based on comparing the average age of death of nearly fifty thousand members of the creative professions.

Until the last two years of Andy’s life, he seemed pretty healthy for a rock musician whose tours were more notable for their gourmet riders than for abstinence. Other bands argued with promoters about smoke machines and lasers; Andy pushed for good food and fine white wines, properly chilled. I remember his exasperation when Glastonbury, on a hot summer’s day, ran out of ice.

At home, by mutual agreement and his personal choice, he lived more moderately, eating well and exercising daily. In his twenties, he underwent an emergency operation to excise a cancerous tumour and, because this was lawsuit-happy America, a string of lymph nodes. The experience left him with a scar from groin to sternum and clips holding him together that could be felt below the skin years later. It may also have underpinned his aversion to end-of-life discussions and his surprising lack of arrogance. Performers can be brittle and needy; he was neither, though he often did tell me, in jest, how lucky I was to be with him and that he was a genius. I would laugh, but both statements were true. We were always lucky, something I felt moved to acknowledge in a statement on the day he died: ‘This pain is the price of extraordinary joy, almost three decades with the best man in the world.’

We met in 1991 at a ‘page forty-six party’. Invitations, in those analogue days, had been extended to people living in the part of Islington mapped out on that page of the London A–Z. Neither of us did.

Our paths crossed by stroke of luck and our good fortune manifested itself in other ways too. No matter that we had marched against her: we belonged to the minority of the population that had thrived during Margaret Thatcher’s premiership. The venue, a warehouse flat with a suspended pool replacing one wall to create a human aquarium, spoke to the affluence of our intersecting social circles, musicians and writers, artists and actors.

Wealth cannot shield you from death. I think, now, of friends at that party. Our hosts were Richard Paxton and Heidi Locher, architects of the flat and of other buildings including Soho Theatre. Richard died suddenly at 49; so too one of their guests, the author Douglas Adams. The barrister, Jane Belson, later Douglas’s wife, was also there that night. She would outlive him by a mere decade.

Yet money certainly gives you better odds of living longer. A life expectancy gap of nearly a decade for men and two-thirds’ that period for women separates the UK’s wealthiest from the poorest. The income gap plays out in bereavement too, in the scrabble to meet the exorbitant costs of death, financial and emotional.

Such thoughts had never troubled my life as I wandered through Rick and Heidi’s flat and laughed at an unfeasibly handsome man who stood next to the buffet, a serving bowl under his arm, scooping out trifle with his hand. Andy hadn’t been able to find a plate or cutlery. We started talking and eventually ended up on the terrace, where he serenaded me with The Drifters’ song, ‘Up on the Roof’. ‘And if this old world starts getting you down,’ he sang, ‘there’s room enough for two.’

We met again the following weekend and never looked back – or much into the future. We were busy and happy. Then, nine years later, a cold wind blew through our Eden. Andy’s university friend Yannis didn’t mean to fall from the flat roof of his apartment block; drunk and arguing with a lover, he lost his footing. The singer Michael Hutchence hadn’t planned to die either, succumbing to a suicidal impulse after a sleepless night and a turbulent few years. Andy and he had been working on an album together; we were godparents to his daughter with Paula Yates. His death left Paula, who was both a cause of the turbulence and Michael’s sanctuary from it, with a double burden of loss and guilt, and ensnared in a skein of administrative wrangles. After one of many rescue missions to her house, summoned by some terrible crisis or her intractable sorrow, I returned home to find Andy in the kitchen, doing the washing up. ‘Do you think we should get married?’ he asked. I supposed so. We had seen in Paula’s struggles that love counted for little in the eyes of the law or the rapacious music industry. She attended our wedding in September 1999. A year later, our friend Jo found her cold and final in her bed, the victim of an accidental overdose.

Michael’s death had plunged Andy into despair and me into coping mode. I tended to him, to Paula, to her daughters. Paula’s death took my breath away – at least half an hour I gasped for air when we woke to the headlines. Then it propelled me into a spiral of activity that I couldn’t, at the time, name. All I knew was that I had never been more productive. I seemed to require neither food nor sleep and often took long walks at night. Scared of further and greater loss, I recoiled from the person I most feared losing, the only person who could comfort me, deluding myself that I needed neither him nor comfort.

Hello grief. So cruel you can be, tearing apart families, setting lovers against each other, urging people in the teeth of involuntary life changes to make more and faster change. Andy and I were lucky, again. After a difficult time, we found our way back, held each other tighter. Others are less fortunate. Grief poisoned my mother’s relationship with her own mother, Ruth. How could she, a child already reeling from the death of her father, cope with the loss of her little brother, much less understand Ruth’s anguish? My mother felt – still feels – that given a choice between her children, my grandmother would have preserved Kenny’s life, directing the lightning bolt at her eldest instead.

These days grief is my familiar, a shadow I know as well as myself; that is to say, not quite as well as I think. Some days its shape-shifting ways still surprise me, a bruise that inflicts bruises. My spatial awareness is shot. Yesterday I walked into a table. This morning, I took a break from writing this chapter and in the kitchen, beneath a new portrait of Andy created in tribute to him by the street artist Shepard Fairey, danced, sobbing, to ‘Up on the Roof’. Another day grief might sit on my chest, immobilising me in an echo of Andy, on his last day at home, laid out and struggling for breath. It isn’t an easy companion, is no substitute for the companionship it replaces. Yet it is more than the price of love. It is love. We, the bereaved, must learn not just to live with it, but to make it welcome.

At 56, Andy was diagnosed with sarcoidosis, an inflammatory disease that can affect any part of the body but in his case targeted the lungs. Initially he mistook his minor breathlessness for a return of the asthma that had troubled him since childhood. He consulted a specialist, George Santis, Professor of Thoracic Medicine and Interventional Bronchoscopy at King’s College Hospital and a consultant physician for Guy’s and St Thomas’s, who prescribed a course of steroids that quickly sorted him out. Recurrences were mild. Then came a bout that hit him harder and responded more slowly to treatment. The steroids, in higher doses, eventually did their stuff, but at a cost. He couldn’t sleep, using the fevered nights to write a new album, developing diabetes as a side-effect of the drug and losing lung capacity to scarring. Professor Santis regularly checked on his progress.

That February, I joined Andy at the start of a Gang of Four tour that would cross the US from the west coast to the midwinter east, culminating in New York. Our arrival coincided with a polar vortex that turned most of the US into a snow globe and unleashed on California sleeting rain. Water dripped from the skylight of the tour bus, pooling on the floor. Already Andy seemed too weak for the slog ahead, endless days on the road, the load-ins and soundchecks, the interviews, the kinetic performances, the backstage revelries abbreviated only once the load-out was completed and the bus set off again. The gigs, though, were brilliant and he was in his element. At The Roxy in Los Angeles, flanked by Shepard Fairey and the musician Tom Morello. I watched Andy smash a guitar and make magnificent noise.

After I flew home, his health declined. In Denver, the altitude, in combination with his reduced lung function, sent him to hospital. He managed to play that night. As the band traversed America, he got sicker, blaming the cold air. By the time they reached Woodstock, he had lost feeling in his legs and had to be carried on to the stage. The next day, his bandmates rebelled, refusing to perform unless he obtained medical assurance that he was fit to do so. He called me from a New York hospital, pleading with me to persuade them to change their minds. Instead I backed them and, after his return to England, urged him to seek medical attention. Our GP took one look at him and sent him straight to hospital. He was there for a few days, then discharged himself. He had work to do.

In retrospect, it’s obvious that I wasn’t alone in my intimations of his mortality. Andy’s nominal reason for concealing his illness was that promoters would stop booking him if they thought him a bad bet. When I study photos of him from that time, I see fear in his eyes. He did his best to maintain focus on the present – Live In the Moment, as he punningly titled a recent live album – and to trust in a future mapped out in tour dates and deadlines. ‘The doctors will just tell me to take more steroids,’ he argued, or ‘All it needs is a bit of warm weather and I’ll be fine.’

When spring arrived, he appeared to be right. We attended a wedding in Hastings in May, a second wedding in the town in July, enjoyed walks along the clifftops. That summer, staying with friends in Spain, I took a photograph of Andy against a fresco in the former monastery of Santes Creus, a skull above his head. In September, in Athens, we celebrated our twentieth wedding anniversary and twenty-ninth year together. The next day we wandered contentedly around the archaeological museum, surrounded by reminders of human transience. Gang of Four played in the city that night. It was the last great performance of theirs I would see, the last anniversary Andy and I would spend together. In my bones I knew what was coming. So why did I not try harder to talk to him about it?

Fear of death is rational. Our responses to that fear more rarely are. We try to outrun mortality, to shield ourselves from the clear, sharp pain of loss. Let me share with you, from a place of pain and in the story of Andy’s death, a lesser ambition: to remove not the pain, but the avoidable stress and distress that too often cloud it.

In the years we were together, Andy and I built and made and created things that required effort and dedication: music, books, campaigns and organisations, and a flat above a recording studio in a space without planning permissions for either. We obtained those permissions and navigated any number of more complex challenges that confronted us during our working lives, including legal skirmishes and lawsuits. We knew our way around forms and institutions. We were well prepared for anything life threw at us – except death. Andy died before making a Will or sharing his last wishes or passwords or the secret of how to fix the television when it goes on the blink.

In a later chapter I touch on the difference planning for the end of life can make for the dying and those they leave. First I must deal with something far more uncomfortable. Did Andy and I, in trying to ignore his fate, advance it? What if instead of collusive silence, I’d offered him a way to admit to and address our mutual fears? Imagine if we’d known how to talk about death as easily as we debated politics or the books we were reading or, a question that preoccupied us, what to have for dinner.

It wasn’t until November, nine months after his hospitalisation and apparent recovery, that I realised quite how tightly braced I was against a relapse. My sisters and I had plotted with our stepmother to arrange a surprise visit to my father on his ninety-first birthday. As we sat in his house in Manchester, a WhatsApp came through from Gang of Four’s tour manager, a photo of the band accepting the applause of the crowd with the simple caption, all in capital letters: ‘WE DID IT!’ I surprised everyone, including myself, by bursting into tears.

The day before, I had messaged the tour manager, concerned that Andy sounded breathless on the phone. ‘Beijing is very cold!’ the tour manager replied. ‘We are all a bit short of breath.’ Now the tour was over, in grand style, a catalogue of full houses and five-star reviews, and my love was coming home.

We’d developed a trick over the years, Andy and I. Instead of reuniting in our flat at the end of his tours, we would book ourselves into a hotel, allowing twenty-four hours to catch up on neutral territory before he crashed back into a space that in his absence was always tidy and quiet. It is tidy and quiet now.

On this occasion, I broke with tradition. I just wanted him back. He looked tired but his lungs didn’t sound too bad, an observation confirmed by his thoracic specialist, Professor Santis, the following week. The day he imparted this encouraging news, my mother took the call from my stepfather to tell her that he wouldn’t be coming home from UCLH for the time being. We commiserated with her and agreed to join her two nights later for a muted celebration of her birthday at a restaurant booked for the occasion by John.

The following days and weeks will be pocked with hollow celebrations, Christmas parties, birthdays, feeble hope vainly flapping its tinsel wing. We visit John in hospital. When my mother is in earshot, he talks of a fictional future. After he dies, the festivities continue. Andy and I bring in the new year with family and friends in Italy. At midnight, someone hands out sparklers. I watch his burn down and cannot stand the symbolism. By this stage it is no longer possible to pretend that he is even remotely OK. If I’d realised how sick he was, I’d never have agreed to travel to this undulating countryside, where paths we used to walk taunt him with their cambers and gradients. On our return to Gatwick, he can no longer manage its flat expanses either. I find a wheelchair and somehow manoeuvre him, our twin cases and computer bags to the train station. I’m lucky, I think, to be strong, just like my mother, who until so recently had wheeled John about the place. I will be Andy’s carer, as she was John’s. Already I am shedding work commitments, rearranging my life to the service of his.

Three years, my mother looked after John. I tell myself I will have longer to tend to Andy. He was born amid a hubbub of new year fireworks. In Italy, at the moment his sparkler splutters its last, he has turned just 64, hardly any age at all.

He and I support each other in our denial. Our fantasies are not the same, though Andy is beginning to acknowledge the possibility that he may have to make some changes. He keeps booking tour dates and working on music, but he also starts looking at property in warmer climates, still trying to convince himself and me that cold air is the culprit. I imagine living in such a place, tranquil and content, enabling Andy to write music. I know that he shouldn’t tour again and wonder what it will take to make him accept this too.

At night, pipe dreams give way to living nightmares. Andy’s specialist has given him a small, portable oxygen supply for the last tour. He didn’t need it on the road; now he depends on it. We sleep to the hiss and pop of its pump.

He takes higher doses of steroids and an immunosuppressant, Methotrexate, to try to dampen what we assume to be a particularly acute episode of sarcoidosis. Despite the steroids, he remains lethargic, dozing through the days and barely moving from our bedroom. When I persuade him to see our GP, she tells him he should be in hospital. He refuses. I discover after Andy’s death that he ignored the same recommendation from Professor Santis. Andy insists that hospitalisation will make him worse. He wants to be at home.

Much later – too late – I will ask questions that I should have pursued, without let-up and to their logical conclusion, no matter how much Andy and I would have hated the answers. The reply I receive from Professor Santis, in its caution and kindness, tells me what I needed to know: that there is a chance, however slight, that the outcome could have been happier if we had acted sooner. ‘It is difficult to know if Andy’s touring contributed to his deterioration,’ he writes. ‘I suspect not… I doubt again if an earlier admission would have made much difference. Unfortunately, it is impossible to answer with any certainty.’

On 18 January, I find Andy slumped in a chair, conscious but colourless. Finally I tell him I am calling an ambulance and even then we bargain. First he must have a bath. Then he asks for a glass of Puligny-Montrachet. I refuse and will always upbraid myself for that pointless rigidity. The paramedic suspects sepsis and summons a blue-light ambulance to take us to St Thomas’s hospital.

Even then we delay its departure. Andy wants his computer with him, external hard drives, address book. He’s planning already to work from his hospital bed. This, too, he will do, right until the moment he is forced to stop. He will cease building a fictive future only when he can no longer breathe.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».