Полная версия

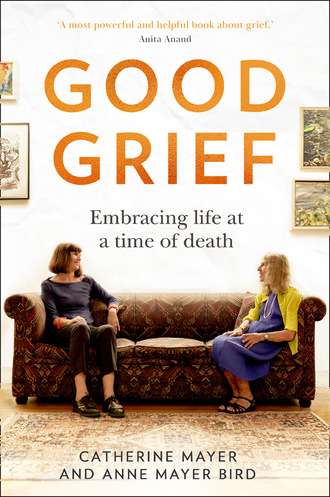

Good Grief

She would tell you herself – she will tell you herself in these pages – that these fears were justified, but that together we found ways to navigate our mutual and intersecting grief and to hold on to the Andyness, the Johnness and our shredded hearts. In this room, this living room, we are learning to embrace the things we can’t touch, each other and the lovely dead.

We hope in sharing our insights and learnings to help those of you who have lost or will lose people you love or who wish to know how best to support others in such circumstances. We don’t pretend to have all the answers or even all the questions, but we believe we can impart at least a few essential examples of both. Death has been having a busy time of it, dashing from one household to the next like a malign Santa Claus. We will talk about the additional challenges to grieving and coping during a pandemic, but most of what we discuss is not specific to this period or these circumstances. It is just that Covid has made these things visible. If humanity can drag any positives from this global tragedy, it will be in addressing the deep dysfunctions the virus uncovered. This book is not a manifesto for equality, though it touches, often, on the tragic consequences of inequality. Covid was never, despite the protestations of politicians, a leveller. On the contrary: it revealed the degree to which some lives are valued more highly than others and some deaths, as a result, disregarded. It also showed the manifold ways in which we are unprepared for the end of life and its aftermath.

Every one of us will die; every one of us will have to deal with death. The central purpose of this book is to make the inevitable better and more bearable.

To that end, although this is not in any sense a handbook, my mother and I seek to distil from our interwoven narratives key lessons not only about grief but about some of the practicalities of bereavement. My mother’s narrative comes in the form of the letters she wrote to John and one she addressed to herself. This book came about after I showed her letters to my publisher, with no intention of writing anything myself. I had found in the letters resonances, learned to understand not just my mother’s grief but my own, and in securing for them a wider audience, I hoped that they might help others in the same way.

In the end, I agreed to write too, about two much-missed men, their widows and a search for truth. In telling our story, I aim to offer an antidote to the numbing effect of charts and undifferentiated death tolls, statistics and numbers. Every death matters because every life matters. This is a memoir of love and loss in the time of corona, of relearning to live in my mother’s living room.

Please join us there.

Chapter 1: Loss

My mother held a party in her living room exactly a week before John died. She was beginning to grapple with a challenge that in pre-pandemic days still confronted the bereaved: how to recalibrate changed personal circumstances to an unchanged world. Life, but for the life that meant the most, would go on. The party gave her brief respite from this growing awareness and, in a small way, modelled a new idea of how she might live without John, alone but not isolated, buoyed by friends and family. She could not know that the virus would soon transform the world too, banishing from her living room all society but mine.

These days we play catch-up, we who are grieving. How should we reimagine our lives when everything around us is in flux? One answer, though not mine, is to follow the dictum of recovery programmes, to take one step at a time. You may find this approach helpful and it is certainly my mother’s default. Throughout John’s illness, she resisted giving much detailed thought to a future without him and instead got on with doing the things that were still possible. As a result, his last years were full of light and vibrancy. When he could no longer walk or breathe without external oxygen, she pushed him in a wheelchair. Though she be but little, she is fierce. They maintained a busy social life. She kept up a considerable workload freelancing as an arts publicist and assisting a theatre company to stage a touring production; he painted. In December, however, ringed by fairy lights and festivities, worries crept through the cracks in her composure. How will I do the supermarket run, she wondered aloud. (John drove, she did not.) Who will cook when I entertain? (For years, John had done all the cooking.)

She still held out hope that John might be home for Christmas, not just the coming holiday but the one after that. They had married on 29 December 1980, and, as John’s health deteriorated, she set her sights on celebrating their fortieth anniversary together. He encouraged this optimism, but never fully shared it; he knew he couldn’t be at the drinks party, but chivvied her to go ahead with it. John recognised in my mother’s focus on small things and increments of time a bottomless fear of something much bigger: losing him. He could cope with his own suffering and wanted to forestall hers.

It was a nice party, with five of their closest friends, and Andy and me, he on fine form, returned recently from a tour that had taken him to Australia, New Zealand, Japan and China. He wore an orange shirt and told vivid stories. Everyone mixed easily. The life my mother and John had built together was intensely sociable, blending different generations and strands from their long and variegated histories. After so many years, more than a few of their pleasures and passions had merged, though she ceded the telly to him when the rugby was on. Both knew what they liked and what, most definitely, they did not. They enjoyed parties and lunches and dinners, trips to the theatre and to galleries. They loathed inactivity and Conservativism.

John was given to declaring some of his deepest aversions on Facebook. On 2 December, he had posted an article from the Independent; its headline: ‘Boris Johnson says salary of £141,000 is “not enough to live on”. He will have to learn to live within his means like the rest of us,’ he commented. ‘Poor boy. It might also help if he kept his zip done up when out with women and stopped creating more arseholes.’

The following morning, an ambulance collected him for a pre-arranged appointment at UCLH, a hospital where he was not only a patient but a former governor. For several years he also served in this voluntary capacity at Moorfields Eye Hospital. John believed in the NHS and in active citizenship. If you wanted a better world, you should help to build it.

He may have been relieved when UCLH decided to keep him in. His conditions – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and a form of blood cancer – were incurable. Steroids to control the COPD had weakened his bones, too. In constant pain from spinal fractures and flares of cellulitis, dependent now not just on ambulatory oxygen but a large compressor that sat in the living room alongside the other paraphernalia of his illness, he might easily be mistaken for someone without joy or reason to go on. After he died, well-meaning friends would say that ‘he had a good innings’ or that ‘it was his time’ or even that his death came as ‘a merciful release’.

The truth was more intricate. It always is. John loved life, loved my mother, still had things he wanted to do. The last place he wanted to be was in this hospital bed. If, as seemed entirely possible, he had more juice left in him, he wanted to come home, to live in the living room with its step-free access to a bathroom. This would require home care. He knew his medical needs had become too complex for my mother to manage on her own. He also looked on the process of dying much as he regarded Boris Johnson, enraged by the fact and stupidity of it and wanting nothing so much as to see the back of it.

Only in that sense was John, at the end, ready to die. His last words, shouted suddenly at a knot of family talking animatedly and pulling him back to consciousness, were ‘shut up’.

Sometimes it is better to keep quiet. There can be a lot of noise around loss, the rattle of hospital trolleys and crematoria conveyor belts, the empty phrases casting death as a blessing. Yet this is not, by any means, an injunction to avoid substantial conversations around death. One aim of this book is to equip you with a better understanding of how to have such conversations and the importance of doing so.

Twenty people close to me I’ve lost in the past twenty-seven years, eleven of whom, including John, I saw at or near the moment of extinction. Those who could still speak had last messages to impart. On the eve of his death, John instructed me to look after my mother; that same day he mentioned to her that she might find another partner. People often presume to speak for the dead. ‘He would have wanted you to be happy,’ they say. John wanted my mother to be happy. I know this because he told me.

The dying often discuss their own predicaments too, seeking not so much comfort as connection. This is helpful to understand, because those grating platitudes about death come from a place of good intention: we want to make the dying and the grieving feel better. It is the wrong ambition. What we should aim for, instead, is to support the dying and the grieving while death or time do their work.

That starts with being honest. I think of a family meal, already tinged with sadness. My stepsister Catherine A has fallen into the excellent custom, since the death of her older sister Sarah, of organising annual gatherings to mark what would have been Sarah’s birthday. The last of these John attended took place an exact calendar month before he died and three days before Andy’s return from China.

A surprise awaited John at Catherine A’s house, a good one. He knew most of his grandchildren would be there, but hadn’t expected to see Sarah’s eldest, newly back from working in Germany. He chatted with her and with all of us. For much of the evening, he seemed himself, which is to say, convivial, interested, game for any conversation, undaunted by age gaps or the hubbub of people talking across each other. Our combined family is generously endowed with opinions and seldom reticent to share them. Andy sometimes found this wearing, but not John; on the contrary, John was always in the thick of it, the Duke of Debate, the Prince of Polemic, arguing his case, laughing, head thrown back with the joy of it all.

This evening, though, he began to flag, in pain and pained to be talked over in his chair. ‘Oh for goodness sake,’ he exclaimed suddenly. ‘Don’t you know that I’m dying?’

In that moment, he needed neither distraction nor soothing words, but recognition of his situation – and of his anger. Just one person I have ever seen greet death without a shred of resentment. Andy’s Auntie June, at 92, yellowed with jaundice but comfortable, had lived with meaning and purpose; at this juncture she could no longer do so. Like John, if she must die, she wanted to get on with the business of dying. Her body’s refusal to let go as fast as she would have liked was the trade-off for a robust constitution that had sustained her through world wars, social and cultural revolutions and repeated proofs of the human capacity to ignore the lessons of history.

Most everyone else whose ending I’ve witnessed railed against extinction, even when that outcome was inevitable and decline merciless. At 97, my paternal grandmother Jane resented the rude interruption to her plans, fighting death to the last. By the time cerebellar ataxia finished off my close friend Richard, just before his forty-eighth birthday, it had stripped him of control over movement, then of movement itself, of speech and of functional eyesight. Still, he dug in his heels. My stepsister Sarah might have been expected, as a committed Christian, to accept mortality easily, but her grace in meeting her fate could not mask the distress of being taken, aged 52, from daughters and a new husband, from a blossoming career in politics and an unfinished thesis.

Sarah died in October 2016. A month later, one of my best friends Sara Burns – I distinguish her from my stepsister by referring to her in these pages as Sara B – finally succumbed to cancer too. She had survived melanoma in her thirties, then twenty years ago received the first of a series of breast cancer diagnoses, by chance in the same week a drug overdose killed another close friend. A short time later, Nicky, my best friend since university, while nursing her youngest child discovered a lump in her breast. It was not, as her GP assured her, a swollen milk gland, but cancer. She would survive, but suddenly I found myself alone among our friendship group to be whole of body if not in spirit.

Sixteen more years Sara B kept going, comforting me throughout that period as if I, not she, were in mortal danger. After a later diagnosis, finally at the edge of any therapies she could tolerate, she asked me to help her campaign for assisted dying. She did this not with a view to shortening her life but to enhancing the life she had left by freeing herself from the fear of a bad death. Maurice, my sister Cassie’s close companion, and Barbara, my former editor and mentor, shared this perspective, and like Sara B died in protracted and painful ways. If help had been at hand to terminate their lives, they might have accepted it, but perhaps later in the process than they originally envisaged. Maurice in his final weeks still talked of projects he hoped to see through. Barbara starved herself to try to escape the last, agonising stanza, but right up to the point of taking such drastic action regretted that her life should be over. The cancer ate at Sara B’s bones and seeded strange tumours, one, jutting below her clavicle, that pressed on her heart and lungs. No matter the pain, something – a will to live, a sense of potential – kept her fighting for ragged breath.

Where there’s life, there’s denial, a final bond between the dying and those who love them. Death breaks the compact, leaving the bereaved to face the truth alone. The stillness of a body is unarguable, non-negotiable. In that moment you understand the stories of the parents fighting in the courts to keep alive children for whom no life, in a meaningful sense, will ever be possible. In that moment you realise that there is a form of loneliness more profound than sitting by a bedside, listening to the mechanical breath of your sweetheart. You knew, intellectually, that there was no hope of a recovery, but you hoped for some kind of a reprieve. You would rather hold a warm, insensate hand than no hand at all.

For my mother, who at 12 saw her father fall dead, and less than a year later lost her only sibling, younger brother Kenny, to a lightning strike – a force so savage and sudden that it serves as its own metaphor – the prospect of watching John die was unbearable. She had limited tolerance for hospital visits even when she hoped to bring him home. After UCLH hung the sign of a swan at his door, signalling to staff his impending death and their changed medical priorities – comfort, peace and no unnecessary intervention – she left for the evening. My sisters and I kept watch over him in turn. Catherine A was with him when he died, quietly she said, an alteration almost imperceptible but equally unmistakable.

It was around 9 p.m. that this happened, a little later when Catherine A called. I was to let my mother know. I paused to tell Andy; he and John had bonded deeply over decades and the experience of holding their own within this family. Andy cried, then held me as I, also crying, rang my mother. She guessed the news as soon as she heard my voice, asked a few, leaden questions and rejected my offer to come over. She later explained that she had been watching an adaptation of A Christmas Carol. When she put down the receiver, she returned, numb, to the television to watch the rest of it. I’m not sure what she did for the rest of that night, whether she wept, whether she slept, whether she felt the sharpness of loss or the dull weight of blanketing shock. Certainly her small fears returned and multiplied in the coming days and weeks, no longer bypassing her defences but amalgamating to create a buzzing distraction from her underlying anguish.

My mother and I write elsewhere in this book about the administrative burden that attends every death and the unintended sting of the phrase that repeatedly drops from the lips of those intending comfort: ‘It’s good to be busy’. Oh no it isn’t, not when that busyness consists of a daily battle with institutional incompetence and bureaucracy, compounded by apprehension about whether you can pay for the funeral, household utilities and basics, whether you can afford to stay put or might need to move. All these things we experienced, and we are the lucky ones, privileged, cushioned. We had assets to sell if we needed to, friends and family who offered to help out.

The only slender positive of dread tape and sadmin is that they occupy headspace that might otherwise brim with thoughts of giving up. So it was that my mother’s campaign to retrieve John’s Nectar points and add them to her own card preoccupied her during the aftermath of John’s death and during Andy’s final days. She informed Sainsbury’s customer services of her aims; instead of assisting her, they suspended John’s card. It took interventions by Cassie and by my mother herself to restore the points.

An outsider might have mistaken her focus for a lack of deeper feeling. How could she care about such a trivial matter when she had lost, so recently, her greatest love and must soon bid farewell to the son-in-law she cherished? The answer, of course, is that trivialities helped to divert her from considerations she could not, at that stage, endure. I grasped only when she began to write her post-mortem letters to John how much she had held in check. The contrast between those letters and the eulogy she wrote for John and asked me to read at his funeral is telling. Lovely though the eulogy was, it told their origin story, about how they met in a wine bar, a tale honed with years of repetition, about them but not, in any depth, about him. She was moved – we all were – by the more detailed tribute their friend Ian delivered at the funeral. It pleased her that he had so well understood and appreciated John. It would be many weeks before she could let herself fully access that understanding and appreciation, because to do so would also confront her with the scale of her loss.

My coping mechanism was different, a swift-onset, selective amnesia. Every minute of Andy’s dying is etched in my memory, but the only reason I can tell you how I got home from the hospital that day is that I recently asked the people most likely to have accompanied me. Apparently Nicky brought me back to the flat, watched over me until I had eaten something and declared myself ready to sleep. Try as I might, I cannot remember anything of this. The following days are a mosaic of coloured pieces and clear glass, memories and absences.

These reactions – my mother’s deflection, my erasure – shared key characteristics: they were involuntary and elemental, a retreat from the full realisation of our circumstances, that in delaying and reducing our engagement with grief made us appear more functional than we were, perhaps even a little detached.

There was a look I caught more than once in those early days – surprise, unease – when I behaved in ways that defied expectations of widowhood. It’s not that I danced or sang or made tasteless jokes (though I’m sure I did make tasteless jokes). It was more that I was still recognisably myself. I had noticed this reaction to my widowed mother before I found myself on its receiving end.

So often the bereaved are judged as if there were a right way to do grief. The form that judgement takes is shaped by wider social attitudes. The irony is not lost on me that as the co-founder of the Women’s Equality Party, it has taken my own widowhood to make me think about how this phenomenon plays out for women. Mourning rituals vary widely across time and cultures but there is a constant: women who survive their spouses are subject to tougher criticisms, customs and rules than other classes of bereaved. ‘If I am to speak of womanly virtues to those of you who will henceforth be widows, let me sum them up in one short admonition,’ said Pericles in his funeral oration for Athenian soldiers who had died in the opening skirmishes of the Peloponnesian War. ‘To a woman not to show more weakness than is natural to her sex is a great glory, and not to be talked about for good or for evil among men.’ Failure to wear widow’s weeds – black clothing signalling their sad status – earned censure for Victorian widows. Queen Victoria drew criticism for the inverse behaviour, wearing widow’s weeds for forty years after the death of Prince Albert, longer than the prissy era that bears her name deemed seemly.

Navigating popular ideas of widowhood can feel like being Goldilocks without the option of the third bowl of porridge. Whatever we choose risks being too hot or too cold. We risk being judged too hot or too cold. Our cultural heritage teems with steamy, rapacious, dangerous widows and their icy antitheses. Black Widow is both a Marvel assassin and the unrelated titular serial killer of a 1987 movie (‘she mates and she kills’). Jane Eyre’s Mrs Reed stares mistily at a miniature of her dead husband but ignores his dying injunction to look after their niece, Jane, as if she were one of their own children. Instead she abuses her, then exiles her to the brutal Lowood School.

Underpinning these uneasy portrayals is a sense that widows, unlike other women, have power. The opposite remains true in swathes of the world where widows are routinely not only deprived of inheritances but treated as inheritance, to be passed on and enslaved. It was coverture, established in English common law in the twelfth century, that by omission granted to spinsters and widows rights not available to their wedded sisters. Under this convention, a married couple became, in economic terms, a single unit. That union saw possessions and other rights passed from bride to groom, making her by extension his chattel. Spinsters, by contrast, retained economic control and widows regained it, even if as women their rights were curtailed in many other respects.

My mother and I, in our deceptive calm, inadvertently tapped into deep-rooted folk memories and prejudices, though Pericles would surely have approved for all the wrong reasons. None of the people urging us to cry more or organise less did so from a position of anything but love. Others, equally benign in their intent, pushed premature life plans at us. Within days of our husbands dying, friends and family had told us we should move from our respective homes or at least avoid staying in them until we had regained strength. Different people react differently to loss, but both of us drew comfort precisely from the reminders we were warned against. We still do. The presence of our dearest departeds is something neither of us wishes to escape.

In truth we were neither strong nor weak, powerful nor fragile. We became all of those things and still are. My mother surprised herself in finding resilience she didn’t know she possessed and coping with tasks and responsibilities she had for years left to John. Nor did she, in those first weeks, show signs of echoing Queen Victoria and withdrawing from the fray, though grief, lockdown and its closure of public toilets diminished her desire to venture far from home. John died on 22 December. On Christmas Day, she arrived at Andy’s and my flat for the family meal I was cooking in John’s stead. She wore a grey, cable-knit dress, patterned tights and ankle boots, with a sparkling of jewellery and her signature lipstick. She looked, acted and interacted almost as if nothing untoward had happened. Later she would ask me if Andy was all right. She noticed that he picked at his food.

She always notices things, and she has a ridiculously good memory, useful for the purposes of this book. I too used reliably to remember certain things – lists, dates, phone numbers – and accretions of detail that didn’t, at the time, seem to matter. Andy mentioned this facility in an interview with the Sunday Times, published two weeks after he died. The journalist Helen Cullen, who spoke to both of us separately for the newspaper’s ‘Relative Values’ series, later sent me the recording of Andy. So strange and moving it was, hearing him from beyond the grave. He recounted an incident back in the early Nineties at the Blueprint Café near Tower Bridge. ‘We went out one evening to a restaurant and the waiter happened to recognise me from Gang of Four, so he was quite chatty and then he said, “What’s your order, madam? Do you want me to bring the menu back?” Catherine said, “No, I can remember it.” “What, all of it?” “Yes, all of it,” and he replied, “I’ll give you a bottle of champagne if you can remember the whole menu.” So she just recited the whole lot, including what came with everything, like twenty dishes. I knew she could do it, but he was very surprised and produced a bottle of champagne.’