Полная версия

Etape

Only one rider had ever stayed out in front on his own for longer in a Tour stage. Albert Bourlon, in 1947, was away for the best part of 253km after attacking near the start of the fourteenth stage in Carcassonne. Nobody else had gone close.

For Pelier, there were two choices. To sit up and go back to the peloton, tail between his legs, and face some gentle mocking from Mínguez, who would be unlikely to give him carte blanche to leave Cubino’s side again. Or carry on.

He carried on, bending his back and elbows to get low over his handlebars and cut into the wind.

There was something Pelier did not realise as he began his lonely effort. Waiting at the finish in Futuroscope were his parents. That was noteworthy because Pelier’s brother was severely handicapped and required twenty-four-hour care. Consequently, although his father had been able to attend a handful of events in his four and a half years as a professional, his mother had never seen him race. They hadn’t planned to travel the 700km from their home in eastern France. But Joël’s brother was in a residential centre for a few days. On the spur of the moment, they decided to drive the six hours from one side of the country to the other, to see their twenty-seven-year-old son in the Tour de France. They didn’t say anything. They wanted to surprise him.

* * *

‘I carried on and my lead kept increasing.’ When it went past nine and a half minutes, Pelier was yellow jersey on the road. But it kept growing, to ten, fifteen, eighteen minutes … ’It was twenty-five minutes at one point,’ Pelier says. ‘But even then, your mood is changing all the time. You believe, you don’t believe, you believe, you don’t believe. I tried to concentrate on managing my effort, and I did that quite well. I wasn’t a young rider; I was experienced.’

Pelier was a typical équipier, or domestique. A team man who, if he ever had individual goals, had learned that if he wanted a professional career he had to forget them. His career had been shaped by such hard lessons. In his first year, 1985, he was riding the Tour de France; they were in the Alps, on the 269km stretch between Morzine and Lans-en-Vercors, and he felt strong. So, in a moment of impulse, he attacked. ‘There were eight cols, and I attacked on the second one. What I didn’t know was that the leaders had decided to neutralise the race until the seventh climb.’

Pelier jumped away when he saw the Colombian, Luis Herrera, sprint for points for the King of the Mountains competition. He didn’t realise Herrera was not attacking: that he only wanted the points on offer at the top of the climb. Herrera sat up, but Pelier carried on. And Bernard Hinault, in the yellow jersey, set off after him. ‘Hinault caught me on the descent, and grabbed my jersey. He said, “What are you doing?” I said, “Don’t touch me!” He was angry and he told me, “You will never win a race!”

‘We had an argument, but then I understood. He was the patron, but afterwards it was exaggerated into a big story by the journalists, who saw Hinault go away on the descent to catch the little idiot who attacked.’

Three years later, as Pelier rode alone towards Futuroscope, Hinault set off in pursuit of him once again. When he caught him, he shouted – again. But Hinault was in a car this time, working for the Tour organisation in retirement, and his yells were of encouragement. He and Pelier had become friends at the 1986 world championships in Colorado, which Pelier rode for the French team, in support of Hinault. Now, as Pelier battled into the wind, Hinault repeatedly pulled alongside, winding down the window to speak to him. ‘He really supported me,’ Pelier says, ‘keeping me up to date with the time gaps, giving me constant encouragement. I think he was happy to see me have a go.’

Hinault knew this was a rare, perhaps unique, opportunity for a rider who had endured mainly misfortune in his career. A year after their run-in at the Tour, Pelier made the headlines again, and once more for the wrong reasons. At the finish of stage seventeen of the 1986 Tour, at the summit of the Col de Granon, he collapsed. It had been a particularly tough and high climb; indeed, the Granon is one of the highest roads in Europe, ascending to 2,413 metres, and steep too. But Pelier didn’t just collapse, he lost consciousness. An oxygen mask was strapped to his face as he was loaded into a helicopter and taken to hospital. Then he slipped into a seven-hour coma. He plays this down, dismissing it as simply the consequence of a ‘massive fringale’ – hunger knock. ‘I was hypoglycaemic. I had to stay in hospital overnight. I recovered quickly but not quick enough. You can’t have a day off at the Tour …’

Pelier’s career refused to run smoothly. Unusually for a French rider, he opted to join a Spanish team, BH, for the 1989 season. ‘I wanted an atmosphere that was warm and welcoming and I found that in Spain,’ he says. ‘I was lucky when I turned professional to ride for two years for Jean de Gribaldy.’ De Gribaldy, known as ‘The Viscount’, died, aged sixty-five, in a road accident on 2 January 1987. Pelier joined Cyrille Guimard’s Système U team the same year. ‘The Viscount is someone I think about often, even today. De Gribaldy loved cycling and loved his riders. And I needed that kind of atmosphere. With Guimard, I found a different atmosphere, one that didn’t work for me.

‘In 1988, I didn’t have a good season and it was difficult to find a team,’ Pelier says. ‘The Spanish put their trust in me and there was another Frenchman, Philippe Bouvatier, who encouraged me to join BH. The Spanish teams were full of grimpeurs [climbers], so they were always on the lookout for riders who could do everything, especially baroudeurs [fighters].’

His decision to cross the border was vindicated when, in April, Pelier crashed and fractured his sacrum, the large pelvic bone. It was another serious setback and yet it served to emphasise Mínguez’s qualities as a manager and his faith in Pelier. ‘I spent all of April, twenty-five days, lying in a plaster. The day of the accident, I thought my season was finished and I cried like a baby in the hospital in Pamplona. I was in a team that had recruited me specifically for the Tour de France. But my directeur sportif, Mínguez, he told me, as I lay in my hospital bed, to focus on getting better and that I could still be there at the Tour.’

‘If there is one rider I want to see at the Tour de France, it’s you,’ Mínguez told him. ‘For me,’ says Pelier, ‘that was huge. Your morale is really fragile when you do sport at this level.

‘You have doubts, of course. After coming out of the plaster and being able to move again, I spent the whole month of May doing rehabilitation. In June, I returned to racing. It was very, very difficult. But I knew Mínguez trusted me, and that helped a lot. It was only fifteen days before the start of the Tour that I began to get on track, to feel that I could reach my previous level.’

* * *

Still, on the road to Futuroscope, Pelier battled the wind and tried to remain focused on the task, crouched over his bike, grinding his way for kilometre after kilometre after kilometre, through largely featureless, flat countryside.

Then it began raining. The roads became greasy and wet, which helped Pelier – there was a big crash in the peloton, and they became cautious. With thirty-eight kilometres to go, Pelier led by eleven minutes. It was a big advantage – there was a full four kilometres between him and the peloton but it was tumbling from the maximum of twenty-five minutes. Pelier’s mind was a jumble of positive and negative thoughts, competing with each other: ‘I tell myself that I’m going to win, then I hear the gap is falling quickly and I think, it’s fucked, I’m going to be caught.’

As the gap began to fall, the sprinters’ teams could smell blood. Greg LeMond was in the yellow jersey and his team, ADR, had been first to take up the chase, reckoning that even a journeyman like Pelier shouldn’t be allowed so much time. Panasonic, the Dutch team, whose sprinter was Jean-Paul van Poppel, then got involved. ‘When the peloton started chasing I was consistently losing time, my lead was really falling,’ Pelier says. ‘But I had been trying to manage my effort. And when they started chasing, I accelerated. I knew I had to spare myself as much as possible, especially in that wind. I was economical with my effort all the time.

‘But the advantage you have, it’s the peloton who decide it. At 100km from the finish, it was feasible for them to catch me. A rider on his own can lose ten minutes in ten kilometres.’

The wind picked up. Pelier’s face was a picture of agony. ‘If Pelier does hit the wall, they’ll wipe him up very quickly indeed,’ said the TV commentator. He turned and hit crosswinds: treacherous in the peloton, but offering some relief to the lone rider. Then it was back into the teeth of the headwind, as torrential rain began to fall, spattering the lens of the TV camera. Through this distorted picture, the viewer could make out Pelier’s grim expression, which spoke of the torture of labouring for four and a half hours into the wind. ‘Pelier looks to be dying ten deaths,’ said the commentator.

With 10km to go, his lead had collapsed to five and a half minutes. Now there was a thunderstorm. ‘It gave me an advantage,’ Pelier says. ‘For one rider, it’s easier in those conditions; in the peloton it’s messy and becomes disorganised. It helped me. But at ten kilometres to go, I was still very worried. I knew they could still catch me.’

Inside the final three kilometres Pelier had entered the pleasure and business park that is Futuroscope. The roads were like a motor-racing circuit: wide and exposed to the full force of the wind. Pelier, as he had been for so much of his ride, was hunched over his bike, getting as low as possible, his upper body rocking as he forced a huge gear round. Earlier he had tried to keep the gears low, spinning his legs, saving his muscles. Now it was all about grunt rather than finesse. He got out of the saddle, searching for more power. Despite the greyness and rain, he kept his sunglasses on, and wore a white headband. A few bedraggled spectators stood at the side of the road, but only the hardy had bothered to come out and brave such atrocious conditions. Still Pelier could not be sure that he would hang on. ‘It was only when I was two kilometres from the finish that I knew I was going to win. I knew then that it was impossible for them to catch me.’

Inside the final kilometre, with barriers lining the road, the crowd didn’t thicken until the final 500 metres. The road rose to the finish and Pelier lifted himself once more out of the saddle. The clock ticked past six hours, 57 minutes. He had spent four and a half hours alone.

Behind Pelier as he approached the line, the official car, containing Hinault, flashed its headlights twice as though in celebration. And then, finally, Pelier sat up, at last able to straighten his back, and wearily lifted his arms. The peloton arrived a minute and a half later: they had been closing all the time.

Beyond the line, Pelier was intercepted by an army of Tour workers clad in Coca-Cola outfits, and behind them the photographers and reporters muscled in as the winner slumped over his handlebars, absolutely exhausted. ‘It was a bit suicidal,’ he managed to tell reporters, ‘because of the headwind. I think nobody behind me believed I could make it to the finish. They all thought they would see me again before the end of the stage.’

Then Pelier looked up, and stretched to see over the crowd. Word had reached him that his parents were there. But he refused to believe it until he saw them with his own eyes, and the TV cameras captured the moment when his face crumpled and tears began streaming down his cheeks. He raced towards them and as he neared his father, reached out, saying, ‘Mon père, mon père!’

It altered the narrative of the stage; surely, thought reporters, Pelier had been spurred on by the knowledge that his parents, Pierre and Janine, were at the finish. But Pelier had no idea. ‘No, absolutely not,’ he says now. ‘It was a total surprise. I didn’t know they had decided to come. To see them at the finish was a big surprise.

‘My dad had had the opportunity to see me at some races in my career, but my mum could never make it because she always cared for my brother, and stayed with him. But my brother was in a specialist centre for the holiday, and it fell during the Tour de France. My parents found themselves with a few days free and alone. It was the first time in six years my mum came to see me in a race. It was very emotional, very special.’

It was evident to all the world when he appeared on the podium and Pelier, jaw quivering and tears still streaming, accepted his prize, and his place in history, with the second longest solo breakaway in Tour history.2

* * *

‘I was married, I had four children, and I was thinking of my future.’ Pelier is talking about his retirement, just over a year after Futuroscope, when he was still only twenty-eight. ‘I had an offer to join LeMond at Z, but in 1990 I had another accident. I fractured my knee in the Tour of Spain. I had to stop for a month and during that period I decided to retire. Having two serious accidents in two years influenced my decision. The career of a sportsman hangs by a thread. A rider is like a Kleenex. Once it’s been used, you throw it away.’

He was offered a job with the Regional Council of Franche-Comté, helping professional sportspeople manage the transition to ‘civilian’ life. ‘They wanted a sportsman to run this and they gave me a budget to put in place a programme that allowed top sportspeople to retrain and find a job after their career.’

Pelier’s own transition did not run smoothly for long. His wife, whom he described as ‘an extraordinary woman’, passed away. And after three years running a programme for ex-athletes, Pelier left to set up his own business, a bike shop. It didn’t work out, and now with five children to look after he struggled with financial problems. These days, he works part-time for the municipal council in the tiny village of Chaux-la-Lotière in Franche-Comté, western France. In this role, Pelier is a handyman who might be cleaning the streets, or clearing rubbish. It is not what he dreamed of, he has said, adding: ‘If it is not rewarding, it is not dishonorable.’

But that is not all. Pelier has something else. Art. He is a sculptor, producing in his workshop magnificent wooden objects, from figurative representations of animals to swirling abstract creations. Some of the abstract objects are large but delicate looking; one could represent an athlete, perhaps a cyclist, head tilted back, arms in the air. ‘Even as a rider, I was passionate about art,’ Pelier says. ‘But I really started in the last ten years and I progressed quite fast. I have a feeling for it, and I now have a job that allows me to do it.’

When the 2012 Tour visited Belfort, close to Pelier’s home, the 1989 stage winner paid a visit. He had something for Bernard Hinault: a wooden sculpture, almost like a giant hand, with five prongs, one to represent each of Hinault’s Tour wins.

As for his previous life: ‘I follow cycling from afar, and the Tour always makes me excited, but I don’t feel the need to go to races.’ The only memento in his wood-carving workshop, where he spends so much time and where he says he feels happiest, is a framed picture of his first mentor, The Viscount, Jean de Gribaldy. ‘I have my life now,’ Pelier says, ‘and I give myself one hundred per cent to that. Cycling is behind me.’

Classement

1 Joël Pelier, France, BH, 6 hours, 57 minutes, 45 secs

2 Eddy Schurer, Holland, TVM, at 1 minute, 34 secs

3 Eric Vanderaerden, Belgium, Panasonic, at 1 minute, 36 secs

4 Adrie van der Poel, Holland, Domex, same time

5 Rudy Dhaenens, Belgium, PDM, s.t.

6 Eddy Planckaert, Belgium, ADR, s.t.

2 Two years later, another Frenchman, Thierry Marie, managed an even longer solo breakaway, staying clear for 234km to win stage six in Le Havre. The record, 253km, still belongs to Albert Bourlon, who died a month short of his 97th birthday in October 2013.

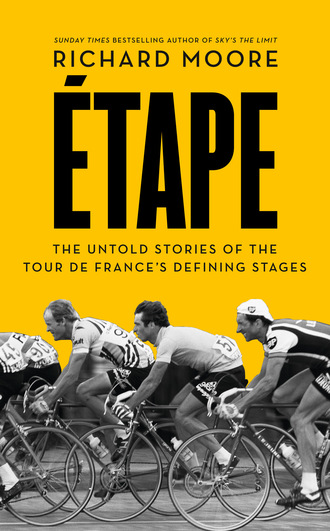

L-R: Thor Hushovd, Mark Cavendish, Gerald Ciolek

24 July 2009. Stage Nineteen: Bourgoin-Jallieu to Aubenas

178km. Undulating

On 20 July, at his hotel in the Swiss Alps, on the second rest day of the 2009 Tour, Mark Cavendish was approached by a rival team manager, Bjarne Riis.

A controversial figure who had admitted to doping when he won the Tour in 1996, Riis was now running the Saxo Bank squad, and one of his riders, Andy Schleck, was still in contention to win the 2009 Tour. As a manager, Riis had earned a reputation as one of the sport’s thinkers and innovators, whose teams were tactically astute and exceptionally well organised. Partly this reputation might have been due to his demeanour: Riis, a Dane, was cold and inscrutable, his aloof manner suggesting he was in possession of a secret code.

But today, Riis had something else on his mind when he walked over to Cavendish’s table as he ate dinner.

‘Have you looked at the profile for stage nineteen, the finish in Aubenas?’ Riis asked.

‘Yeah,’ said Cavendish. ‘Kind of. Looks like a massive climb at the end.’

‘You can get over it. We trained around there. The first half – the first three or four ks – are hard, but if you can get over that, you can settle into it. The last 10km are steady.’

‘Really?’

‘You can go for that one.’

The riders were coming out of the Alps, heading west: the stage was a bridge to the final mountain of the Tour, on the penultimate day: Mont Ventoux. But the stage Riis was talking Cavendish into – stage nineteen, from Bourgoin-Jallieu, in the Rhône-Alpes, into the Ardèche valley, then on to the town of Aubenas – was anything but flat. It was mountainous; the etymological root of the town’s name, ‘Alb-’, means ‘height’. Aubenas sits on a hill overlooking the valley.

It was the kind of stage that Cavendish, the best sprinter of his or perhaps any other generation, would have studied and then probably dismissed. Cavendish and Riis had this in common, if nothing else: both were assiduous in their preparation. Every evening, while some riders were playing computer games or phoning home, Cavendish would study the official road book: the bible of the Tour, detailing every village, every hill, every bend in the road, along with brief tourist-style descriptions of the start and finish towns (‘Aubenas,’ read the entry for stage nineteen, ‘perched on a rocky spur overlooking the Ardèche Valley, with a population of 12,000, benefits from the temperament, the accent and the radiant smile of the south. In the summer, the sunlight illuminates the treasures of the town, captivating the senses of those who visit the city of the Montlaurs …’).

When Cavendish looked at the profile for the stage to Aubenas, it did not look promising. A lumpy first 50km included two category-four climbs, and four peaks in total: up, down, up, down, up, down, up. These so-called ‘transitional’ stages can be the hardest of all. There would be too many riders who would fancy their chances. And it would be their last one, with Ventoux reserved for the overall contenders, and the Champs-Élysées, on the final day, reserved for the sprinters: for Cavendish.

It was the final week; everyone was tired. Nerves were frayed, tempers were short. The day before the stage to Aubenas was a time trial around Lake Annecy, over 40.5km, which Cavendish wanted to treat as another ‘rest’ day. Only, it didn’t quite work out like that. When he heard his time, at half-distance, he realised there was a danger he could finish outside the time limit and be eliminated. He had to ride the second half almost flat out. And he had wasted some seconds – and expended needless nervous energy – when he rode past some British fans on the hill. ‘Cavendish, get up off your arse!’ yelled one. Cavendish briefly stopped pedalling, glared at the spectator, and yelled back his own insult.

It was typical Cavendish. But in the end he comfortably made the time limit in the time trial: 126th, five and a half minutes down on Alberto Contador.

He had already won four stages at the 2009 Tour, the same as in 2008, when he didn’t finish, pulling out with a week to go. Now he was going to finish, at least. But for Cavendish, ‘at least’ was never enough. Still only twenty-four, this feisty, edgy young man from the Isle of Man already had the air and attitude of someone who knew he was capable of something special. He was cocky; he carried himself with the swagger of a boxer rather than a cyclist.

He wasn’t big-headed, he said after explaining that he was the fastest sprinter in the world. It was just a fact. How could telling the truth be construed as arrogance? Never mind that he was speaking in June 2008, before he had won any stages of the Tour. He had a point, and it wasn’t long before he hammered it home. When he sprinted to those four stage wins in 2008, it was an arresting sight. He was unlike any other sprinter. He was Usain Bolt in reverse. Just as the giant Bolt broke the mould among track sprinters, so did Cavendish, a diminutive five foot nine in a field of six-plus monsters. Low-slung, weight forward, elbows bent to about seventy degrees, nose almost touching his handlebars, he resembled a cycle-borne missile. Perhaps only Djamolidine Abdoujaparov, the ‘Tashkent Terror’ of the 1990s, looked so fast. Alongside Cavendish and the equally diminutive Abdoujaparov, other sprinters were bigger, more powerful, and punched a larger hole in the air. Unlike the crash-prone Abdoujaparov, Cavendish could ride his bike in a straight line. In fact, his bike-handling skills were extraordinary, honed by riding on the steep, sloping boards of the velodrome in fast, chaotic madison races.

Cavendish was a bundle of contradictions. Hot-headed yet analytical. Supremely self-confident and yet, at times, cripplingly self-conscious. Highly sensitive – he would burst into tears and declare his love for his team-mates – and at times coarse and aggressive. Just ask those British fans in Annecy. Blessed with intelligence, but sometimes unable – to his own frustration – to express himself as he would like.

He worried about his Scouse-sounding Isle of Man accent; about how people would judge him. ‘Although I talk like an idiot, I’m not really a fool, like,’ he tells me. Then there was the question of his athletic ability: were his gifts of the body or mind? As a teenager, Cavendish famously ‘failed’ the lab test designed by the British Cycling Academy to weed out those who didn’t have the physiology to make it as a professional; he was given a reprieve, and went on to become not just a decent rider, but one of the greatest. Whatever his physical gifts, one thing was certain: his desire. Cavendish didn’t seem to want success; he needed it. And he had decided, long ago, that he would have it.

There was something else. His ability to analyse what happened in the frenetic closing kilometres and metres of a stage of the Tour de France was uncanny, even a little spooky. It was as though Cavendish had been watching the action unfold not from ground level, but from the air; as if he had access to the TV camera in the helicopter hovering overhead. Call it spatial awareness, or peripheral vision; whatever it was, Cavendish seemed able, invariably, not only to be in the right place, but to know what was happening around and behind him: where riders or teams were moving up fast, or slowing down, or switching; and adjusting his position accordingly to emerge from the mêlée and throw his arms in the air in victory. (The peloton might look organised and fluid, even serene at times. It’s not. And in the final kilometres, it’s chaos. A neo-pro, Joe Dombrowski, sums it up best: ‘People don’t realise how argy-bargy it is. When you watch it on TV, it looks like everybody just nicely rides together and occasionally there’s a crash. But it’s a constant fight for position.’)