Полная версия

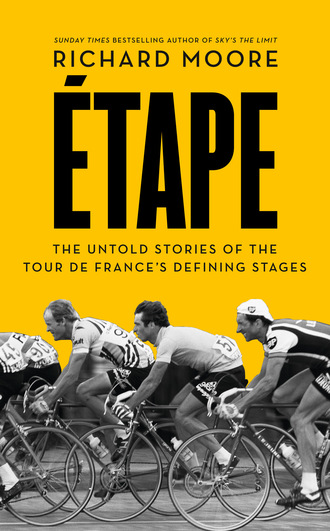

Etape

‘Let me give you an example. Sometimes he would say, “I’m dead, I’m not good today.” We’d say, “Come on Willie, you have to do it – come on.” And when he saw the sign for three or four kilometres to go, at that point he turned into a beast. I don’t mean in a bad way. It was an instinct he had. He wasn’t arrogant or aggressive, but he could say: “I’m going to win here; nobody else,” and he could beat Cipollini, Abdoujaparov – anybody. And he was a friendly guy, with no enemies. Everybody respected him.’

In his pomp, Nelissen explained this transformation: ‘A sprinter has to be like that. The trick is to get me mad.’ He compared it to road rage: ‘There was a guy once who didn’t give way and he started beeping his horn at me. When something like that happens, I’m ready to jump out of the car. People have to hold me down or I would explode. Well, that’s the feeling I get when I start a sprint. That’s how I get going, get the adrenaline flowing, like fireworks going off. In the sprint, I would kill or eat somebody, but after the line the calmness returns.’

The 1993 Tour was set for a battle royal between the three supreme sprinters of this golden generation. The opening stages confirmed it. Cipollini won stage one, Nelissen won stage two, Abdoujaparov won stage three. But it was Nelissen who wore the yellow jersey for two days after his stage win, then reclaimed it for one more day after stage five. Cipollini fled when the race reached the mountains to spend the rest of July on the beach – as he always did. (The Giro represented the main dish to Cipollini; the Tour was dessert. But then he wasn’t a dessert man – he never finished the Tour.) That year, there were no more bunch sprints until two days from Paris, where Abdoujaparov won the classic sprinters’ finish into Bordeaux and then laid to rest the ghost of 1991 by winning on the Champs-Élysées.

It was all set for 1994, though Cipollini didn’t make it to Lille for the Grand Départ; he was recovering from a horrific crash at the Vuelta a España, when he was taken across the road and into the barriers by a team-mate, landing heavily on his head (he wasn’t wearing a helmet). There were fears his career could be over. It wasn’t. Like Abdoujaparov, and all the rest, he would be back.

This is where sprinters are different to retired golfers. They don’t lose their balls.

* * *

Not a lot was happening on stage one of the 1994 Tour. The riders rolled out of Lille at 10.45am; it was a warm and sunny day, in the high 20s. Chris Boardman was in the yellow jersey, having won the prologue. For Miguel Indurain, going for his fourth overall win in a row, a flat stage in northern France posed only a little more danger than a rest day. Boardman’s Gan team, which included Greg LeMond in his final Tour, took control in the later stages, after a three-man break had finally escaped with 67km to go, building a lead of almost two minutes. Until then, the bunch was fanned across the road, only coming to life for two bonus sprints, both won by Abdoujaparov.

The Gan team reeled in the break, then Nelissen’s Novemail took over. Typically for a Peter Post-run team, they had strong rouleurs like Marc Sergeant, Gerrit de Vries and Guy Nulens. Untypically, they also had French riders, mainly stage race specialists and climbers – Charly Mottet, coming towards the end of his career, Bruno Cornillet, Ronan Pensec and Philippe Louviot – owing to the fact that the sponsor was French.

With 50km to go, Sergeant, who would be the ‘last man’ in the sprint train at the end, went back to the team car to collect a helmet for Nelissen. ‘I remembered later that evening that I had got him his helmet,’ says Sergeant. ‘Willie was used to wearing a helmet because in Belgium it was an obligation. Not in France, but in Belgium and the Netherlands.’

The Novemail team took full responsibility as they approached Armentières, their royal blue jerseys forming the arrowhead as they entered the town to begin a 5km loop. At the back of the lead-out train sat Nelissen in his black, yellow and red Belgian champion’s jersey. The peloton was stretched in a long line behind. They began the loop: ‘That’s where it will get dangerous,’ said the TV commentator Paul Sherwen. ‘Lots of chicanes and road furniture. It’s going to be very dangerous out there, that’s one thing for sure.’

There were four team-mates ahead of Nelissen. But were they going too early? Sherwen thought so. ‘Too much, too soon for Novemail,’ he said as Mottet completed his turn, swung over, and Nelissen’s team was suddenly displaced by the pale pink jerseys of the German Telekom team, working for Olaf Ludwig. By now, Nelissen had only one team-mate left. Sergeant.

Sergeant stuck to the task. He didn’t drift back too far, to be overwhelmed by the peloton. He stayed near the front, telling Nelissen not to move; to remain glued to his back wheel. ‘I was his guy,’ says Sergeant. ‘He trusted me; he followed me everywhere.’ Nelissen called Sergeant his ‘guardian angel’.

Under the flamme rouge to signify one kilometre to go and there are now three Telekom riders on the front. Sergeant is fourth, Nelissen fifth. The road is narrow and twisting and the peloton, still a long, thin line, is travelling at 60kph. If you aren’t in the top twenty now, forget it. Abdoujaparov is there, so is Laurent Jalabert, fresh from his seven stage wins at the Vuelta.

At 550 metres to go, Sergeant spots a gap and makes his move. He takes Nelissen up the inside as they come round a sweeping right-hand bend with 400 to go. Abdoujaparov is on Nelissen’s wheel. Now Sergeant hits the front. Nelissen launches himself, sprinting up the inside. Abdou goes at the same time, drawing level. With 150 metres to go, they enter a right-hand bend. Jalabert is on Nelissen’s wheel, waiting for a gap.

Nelissen is sprinting, head down. He drifts a little to his right, towards the barriers, and then he disappears. One second he’s there, then he’s not. The sound is an explosion; and it looks as if a bomb has gone off.

Sergeant, having sat up to drift back through the peloton, sees nothing. It is his ears that tell him what happens. ‘As Willie passed me, my work was done. I was à bloc [exhausted]. But a few seconds later there was a huge noise – it sounded like two cars had hit each other. An extraordinary noise. In the next instant, there were people and bikes everywhere. I went through it, I don’t know how. I didn’t brake. I crossed the line, then looked back.’

In the confusion, it was thought that Nelissen had repeated Abdoujaparov’s error and clipped one of the barriers. This is what the TV commentators, as shocked as anyone, tell us. But it is not what happened; a slow-motion replay makes it clear.

It shows that, as the heaving bunch raced towards the finish, there was a man standing in the road. Wearing a pale blue shirt and dark trousers, he is a gendarme. His hands are in front of his face, as though he is taking a photograph. He is taking a photograph. He doesn’t move; doesn’t seem aware that the riders are so close. Nelissen slams into him, throwing him into the air. Simultaneously, another gendarme, 10 metres further up the road, takes swift evasive action, leaping on to the barrier. As the riders continue to stream past, the gendarme who was hit somehow clambers back to his feet and gropes for the barriers.

The photographers, camped beyond the finishing line, scurry forward to the stricken figures of Nelissen and Jalabert. The right side of Nelissen’s face is swollen and bleeding; his eyes are open and staring and his chest heaves up and down. He looks in shock. Jalabert’s face is bloody and he is spitting more; he has shattered collarbones and cheekbones, and four of his teeth are somewhere on the road. Fabiano Fontanelli is the third rider seriously injured; he too is out of the Tour.

The helmet Sergeant had collected for his leader might have saved his life, but now it created a problem. ‘Nobody could understand the system for releasing Willie’s helmet,’ Sergeant says. ‘He was breathing heavily, his eyes going left, right – it was pretty scary. I was able to help. I released the helmet.’

Not only had Sergeant collected the helmet, he had also come to his leader’s rescue. A guardian angel, indeed.

* * *

Every time you watch it, you wince. It is even more sickening than Abdoujaparov’s crash in Paris, than Cipollini’s at the Vuelta, because of the collision with the stationary policeman, who is upended like a skittle. You watch it and think: how did he survive?

‘Immediately after, for ten, fifteen minutes, there was panic,’ Sergeant says of the aftermath. ‘Willie was conscious but couldn’t remember anything from the whole race, the whole day. We all went to see him later, but he couldn’t remember anything. It was a disaster for our team: we were really focused on Willie for stages and the yellow jersey. But in the evening I thought about the fact I had gone back to get him his helmet. I think that was really important.’

In hospital in Lille, Nelissen woke at one in the morning, still in the emergency department. ‘What am I doing here?’ he asked his wife, Anja. Then: ‘Did I win?’

There was a body in the bed next to him: Jalabert. Later he was shown the TV footage of the crash, and asked: ‘Is that me?’ He then asked the doctor how he was still alive. ‘Typical reflexes of a sprinter,’ the doctor said. ‘As soon as he feels something, he tenses all his muscles.’ Apart from his facial injuries, Nelissen suffered three displaced discs in his back. He was lucky.

The inquest began. ‘The policeman had his hand over his eyes, possibly taking a picture,’ said Jean-Marie Leblanc, the Tour de France director, the next day. ‘Nelissen was not looking, but he apparently did not make a mistake. It was the policeman’s behaviour which caused the crash.’

The policeman, twenty-six-year-old Christophe Gendron, suffered a double leg fracture. He was arguably even luckier than Nelissen. He was taken to the same hospital. He was not allowed to speak to the media, so he couldn’t deny reports that he had been taking a photograph on behalf of a little girl in the crowd. It was said that she had asked him, and he had taken her camera across the barrier.

A few months later, the recuperating Nelissen gave an interview to the Belgian journalist Noël Truyers. He was having some problems with his fingers. He had tried to assemble a wardrobe but couldn’t do it, and in the end smashed it with a hammer. ‘Everything about the crash I only know through what other people told me and from what I saw on the telly,’ Nelissen said. ‘The mechanic has thrown away my bike. The forks were broken, the frame was in two pieces. The rest is somewhere in my house: shoes that I cannot wear any more; shirt and shorts that seem to have come out of the shredder; my helmet broken into four pieces …

‘Damn, I regret this fall,’ Nelissen said, ‘because I’m sure I would have won the stage.’

It was almost overlooked, but Abdoujaparov, for once, was blameless: he sailed past the wreckage to win the stage. That was what seemed to irritate Nelissen most. ‘Everybody says that I couldn’t get past Abdou. Come on, guys, Abdou was dying, and I was just getting the 53x11 [gear] up to speed. It was the first time I used this particular gear. I had tested it a few times before, and now I wanted to score big time. You would have seen quite something …

‘They also say that if I hadn’t crashed into that policeman, I would have crashed into the barrier anyway. Everybody who says so doesn’t understand a sprinter. We have an instinct. I can feel obstacles, I can smell a barrier. We just don’t take policemen who take pictures into account.’

Even if Nelissen couldn’t remember what had happened, his body offered a daily reminder. He called them ‘souvenirs’: the scars on his knee, on his fingers and above his right eye. But that winter he was already thinking about his comeback. He attended races, where he was a star attraction. At a criterium in the Netherlands a young fan approached, open-mouthed. ‘Nelissen, is it really you?’ In France a policeman asked if he would pose with him for a photograph. ‘Too bad I don’t speak French,’ said Nelissen. ‘I would have asked him if he could make some speeding tickets go away.’ He posed for the photograph anyway.

Nelissen had no qualms about returning to the sport, he told Truyers. ‘There are always risks, but I’m not scared. I need risks, because of the thrill. They excite me, ignite the fire. I love to be challenged. I once bought a horse, just because it threw everybody out of the saddle. I’m a daredevil, but I’m not reckless.

‘I’ll never let go of the handlebars during a sprint. I never let somebody box me in. If someone pushes me, I’ll return the favour.’ And yet he admitted that one aspect of Armentières would influence him. ‘From now on, I will look out carefully to see if there’s danger on the horizon, like the Indians do, but then I will immediately look down.

‘I only fear one thing actually,’ Nelissen continued. ‘When I see the images of Armentières, I realise that I had a lot of luck. I fear that my chances to come away like that again in a similar incident are very small.’

* * *

It was as though Armentières had never happened. The following season, Nelissen won two stages at Paris–Nice, one at the Four Days of Dunkirk, one at Midi Libre. He replaced his shredded Belgian champion’s jersey: he won the national title again. The next year, he carried on: a stage at Paris–Nice, three at Étoile de Bessèges.

Then came Ghent–Wevelgem in March 1996 and the realisation of his one fear. It wasn’t a sprint; mid-race, Nelissen collided at high speed with a concrete bollard by the side of the road. He was aware of everything this time: lying on the road screaming in agony, his right kneecap crushed, cruciate ligaments ripped apart, femur and tibia broken, pelvis cracked. He lost two litres of blood and underwent emergency surgery at Ghent University Hospital.

‘As far as I’m concerned, he should never get back on a bike again,’ said Anja. ‘If he told me that he was going to stop cycling, I’d be happy. I admit there are crashes in this sport, but why is he so often among the victims? And why is it so serious each time?’

Nelissen returned again with a lower division team. But the after-effects of the crash were profound. The knee gave him constant pain; he could barely ride 40km. He had three more rounds of surgery, then admitted defeat. Nelissen retired in 1998, aged twenty-eight.

* * *

These days, Nelissen lives in Kerniel, in east Belgium. He and Anja split up but he has a new partner, Viviane. And he runs a courier company, Nama Transport.

The difficulty in contacting Nelissen owes nothing to his reluctance to speak. He is no recluse. He is simply – unusually for a Belgian ex-professional – no longer involved in the sport of cycling. He was for a while; he ran a youth team for six years. But no other door opened, partly, he thinks, because he only really worked with two team directors, Peter Post, who retired, and Jean-Luc Vandenbroucke, with whom, he says, ‘I was constantly fighting.’ He still follows the sport ‘very closely, but if you look around my living room, you won’t find any cycling memorabilia, apart from the trophy for my second victory in de Omloop [Het Volk]. Even my Belgian jerseys I gave away.’

He is still regularly asked about Armentières. It is what he is remembered for. Which is ironic, because he still remembers nothing. ‘It has never come back. What I do remember now are the kilometres leading up to the finish. A lot of twisting and turning. Very fast. But the fall … nothing.

‘My first memory is waking up in the hospital. I had no idea what had happened. I knew – because I was hospitalised – that something had happened to me. But I couldn’t figure out what it was exactly. I had no broken bones or anything like that. How? Why? I had no idea. In the early morning, people started coming in, but I didn’t really speak French back then. So it was still a bit unclear. There was a television in the hospital that you had to keep going by putting coins in it. Believe it or not, that started showing the images of the race, and just when the sprint was about to happen I ran out of money! So even then I didn’t see the crash.

‘I didn’t see Jalabert in the hospital. I saw a man on a stretcher, but had no idea it was Jalabert. I just saw a lot of blood.’

Nelissen didn’t see the policeman, either. Nor did he hear from him. In his interview with Truyers in the winter of 1994, Nelissen said: ‘People say he was given a camera by a girl behind the barrier and he took the picture to do her a favour.’ Even if that were true – and it was never proven – Nelissen remarked that it was ‘very sweet of him, but not allowed. He was there to secure our safety, which didn’t happen.

‘It’s unfortunate, but he didn’t do it deliberately. Therefore I didn’t want to press charges, even though there was a lot of pressure from the team. That would just have caused a lot of misery and pain. For him, it would have been terrible; he would have lost his job, his house. That, I would have never wanted. I don’t want him to pay for the rest of his life.’

Gendron, the gendarme, worked for the French army unit CRS-3 in Quincy-sous-Sénart, though Nelissen understood that he moved – or was moved, perhaps – to the south of France with his wife and young child after the incident. The crash in Armentières was the subject of a subsequent police investigation, but Gendron was cleared of any wrongdoing.

At the time, would Nelissen have wanted to see him? ‘Huh,’ he says. ‘An apology would have been nice … I did hear stories later on that he lost his house … But what do you make of stories like that?’

Peter Post estimated that the cost to Nelissen in lost earnings was around £2 million. And although, as Nelissen told Truyers, the rider did not want to pursue Gendron through the courts, Post felt differently. ‘Peter Post didn’t want to leave it,’ Nelissen says now. ‘But what happened in court exactly, I don’t know. I personally got 65,000 Belgian Francs [about 1,500 Euros]. That’s what the policeman had to pay me. But what he had to pay to Peter Post, to the team, I don’t know. There was a legal case; I had to deposit my [medical] expenses, my bills. But I never appeared in court. I was just given this compensation.’

Nelissen recalls that he was back on his bike just two weeks after the crash. Really, he says, his injuries were not that bad. It was a miracle. It could also be partly why he harbours no ill feeling towards the policeman. On the contrary, he is remarkably generous. ‘If you hear what happened, that he took a picture for a little child,’ he says now, ‘well, everybody makes mistakes in life. He has been punished very hard for it. But I don’t really know what happened to him; I heard so many stories, it’s impossible for me to figure out what is true and what is not.’

The legacy of the crash for Nelissen is a scar above his eye and problems with his back: ‘I had three hernias that go back to the crash. My spine was damaged, but the helmet took the blow, that’s for sure. You need some luck in life.’ But he is known for his bad luck. ‘Yeah, but I was still lucky in a way. It could have been worse. That’s how I see it. I can be grateful for still being here. After my last accident [at Ghent–Wevelgem], I’m lucky to still have a right leg.

‘People have often told me I was born unlucky, but that’s not how I see it. The young rider in the Tour [Fabio Casartelli, who died in a crash in 1995], then [Andrei] Kivilev [who died in a crash in 2003], these riders didn’t have my luck. I have to see the positive.’

He still follows the sport, he says. But he doesn’t ride a bike. ‘Let me put it this way: if I do ride on two wheels, it’s on a motorbike. Nothing else. I drive a Harley-Davidson now, which I bought last year. I had one before, but now I changed it for a heavier model. A bit easier, more comfortable. Bike riding, no. No time and no motivation.’

And no fear of speed? ‘No, not at all. But I know the dangers of riding on two wheels. I take everything into account: rain, road surface, if there are small stones … I try to anticipate, because that’s when it’s dangerous. If you’ve ridden on two wheels so many times in the past, and you’ve fallen so many times, then you know what can happen.’

Nelissen appears content. The only experience that can induce anxiety is the place itself: Armentières. ‘I still get goosebumps when I pass through that neighbourhood. Which happens quite often, riding home from Calais. Same for Lovendegem [where he crashed at Ghent–Wevelgem]; you realise, this is where I fell. Lovendegem is worse, because that was fin de carrière. When I enter that town now, it’s strange. I deliver there, so I am there often. It’s not fear, just a strange feeling. This is where it all turned into shit.’

Armentières doesn’t quite hold the same memories. As Nelissen puts it: ‘There is nothing for me to forget, because I don’t remember anything.’

Classement

1 Djamolidine Abdoujaparov, Uzbekistan, Polti, 5 hours, 46 minutes, 16 secs

2 Olaf Ludwig, Germany, Panasonic, same time

3 Johan Museeuw, Belgium, Mapei, s.t.

4 Silvio Martinello, Italy, Mercatone Uno, s.t.

5 Andrei Tchmil, Russia, Lotto, s.t.

6 Ján Svorada, Czech, Lampre, s.t.

Joël Pelier

7 July 1989. Stage Six: Rennes to Futuroscope.

259km. Flat.

On the morning of the first road stage of the 1989 Tour de France, Joël Pelier told his team director, Javier Mínguez: ‘I would like to attack today.’

‘Joël, you know why you’re paid,’ Mínguez replied. ‘To protect Cubino.’

‘I was an équipier,’ Pelier explains, ‘so I worked for my team leader.’ Laudelino Cubino was a typical Spanish climber. ‘Forty kilogrammes soaking wet and he couldn’t ride at 60kph on the flat. I was his guardian angel.

‘When you’re an équipier,’ Pelier continues, ‘you don’t have any possibilities for yourself.’ But five days later, during stage six, Mínguez had a change of heart. ‘I don’t know why,’ Pelier says, ‘but he gave me carte blanche. During the stage, I went back to the car to get a rain jacket and bidons. There were about 180km left, and he asked me why I didn’t attack. It was like he was challenging me. He told me he didn’t think I had the balls to attack because there were too many kilometres left. He was laughing, but it was like a bet, or a challenge.’

It was the longest stage of the 1989 Tour: a grey, dreary slog south from Rennes, the capital of Brittany, down to Futuroscope, the futuristic but still unfinished theme park on the outskirts of Poitiers in western France. It was overcast and the stage, a bit like the theme park, promised little in the way of excitement. An unseasonably chilly wind blew directly into the faces of the riders, and they huddled together for shelter. The conditions did not suit a breakaway, the headwind favouring a large pack of riders over any small group. It was a day when there was strength in numbers.

After 31km, Søren Lilholt won an intermediate sprint. Sean Kelly won the second at 58km. John Talen took a third after 75km. Still the peloton was all together. In the lull that followed the third sprint, Pelier dropped back to the team car for his rain jacket and some bottles. And Mínguez joked, ‘Why don’t you attack?’

Pelier rode back up to the peloton, gave the bottles to his team-mates, the rain cape to Cubino, and made his way to the front. Then he proved to Mínguez that he did have balls. He attacked. ‘I thought there were others following me, but the peloton seemed surprised. So I used the surprise to go on my own. And I built a minute’s lead really quickly. But there were 180km left. On your own, that’s suicidal. You know that, because it’s such a long way, a breakaway is going to be destined for failure.’