Полная версия

Napoleon

What he found on arrival was not encouraging. The besieging army’s headquarters at Ollioules were a nest of political intrigue and infighting between Carteaux and General Jean La Poype, who had joined him with 3,000 men from the Army of Italy. Anyone could see that Toulon was all but impregnable and that only bombardment could yield results, but as Buonaparte quickly realised, Carteaux had no idea how to lay siege to a city. He insisted that he would capture it ‘à l’arme blanche’, that is to say with sword and bayonet, and ignored Buonaparte’s advice.8

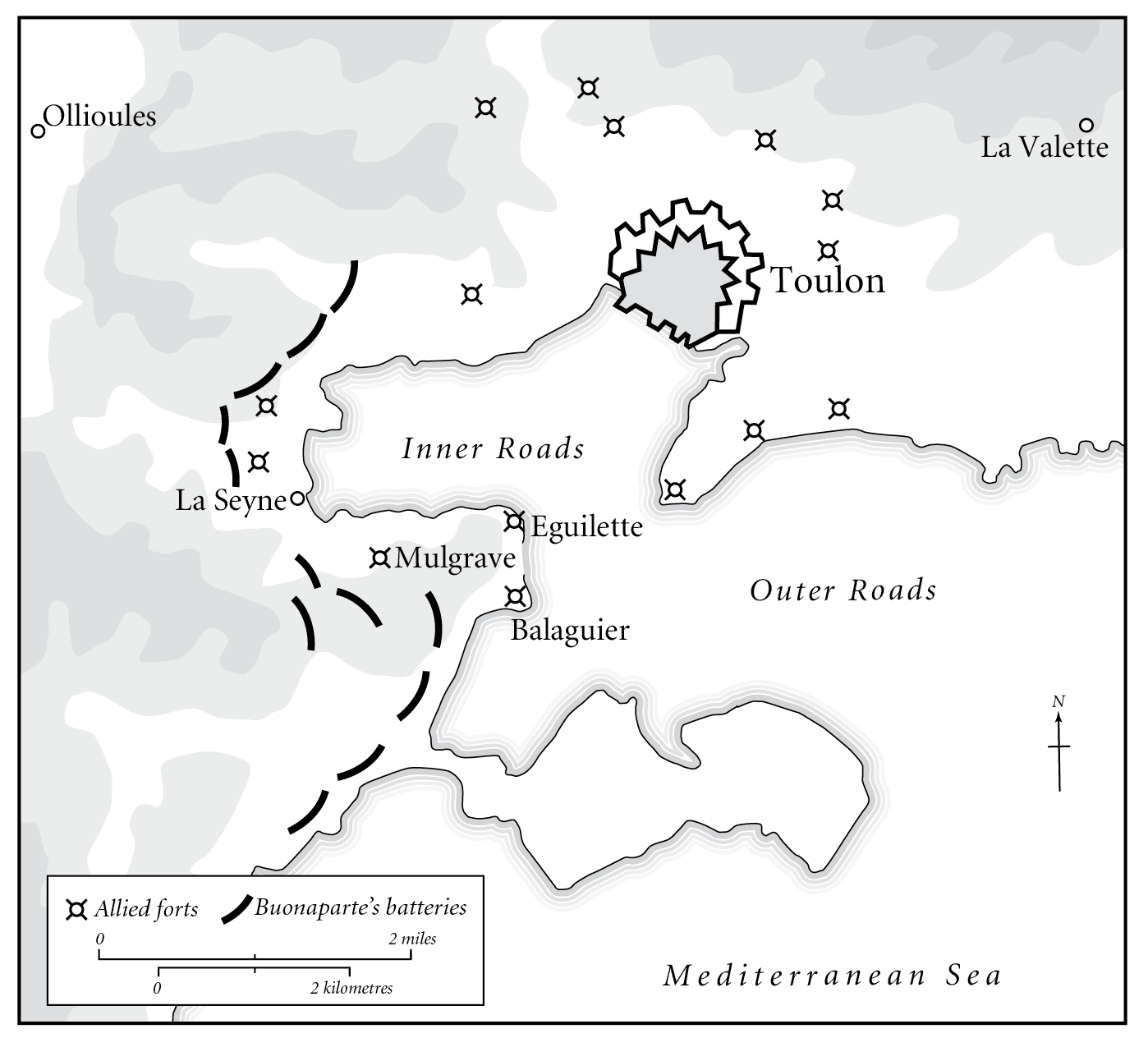

If Toulon was impregnable on the landward side, it could not hold out unless it was resupplied by sea, and no ship could approach the harbour if the heights commanding the roads were not secured. Buonaparte was not the first to see that capturing these was the key to taking the city – it was obvious from a glance at the map, as even the governing Committee of Public Safety in Paris had pointed out. But while most of those at headquarters saw the area of La Seyne on the inner roads as the place from which to threaten the allied fleet, Buonaparte believed that it was the two forts of Balaguier and Éguillette on the promontory of Le Caire, commanding access to the outer roads, that were crucial. They were held by allied troops, and it would take artillery to dislodge them. But all Buonaparte found on arrival were two twenty-four-pounders, two sixteen-pounders and two mortars. It was not much to be going on with, but enough to enable him to chase an allied force and a frigate away from the La Seyne area and set up a battery there which he named, to stress his loyalty, La Montagne.9

Over the next weeks, Buonaparte built up his artillery park. Not bothering to seek authorisation, he scoured the surrounding area, visiting every military post as far afield as Lyon, Grenoble and Antibes and stripping them of everything that might come in useful – cannon, gun carriages, powder and shot, tools and scrap metal, horses and carts, along with any men who had ever handled ordnance. He set up a foundry to produce cannonballs, forges to supply iron fittings for gun carriages and limbers, and ovens to heat the balls to set ships on fire. He also picked men from the ranks to train as gunners.

The first attack on Fort Éguillette on 22 September was a failure. Carteaux did not share Buonaparte’s conviction about the fort’s importance and deployed too few men, while the British quickly brought up reinforcements. They realised the French had identified the military significance of the promontory, and reinforced the position with a new battery which they named Fort Mulgrave. They added two earthworks on its flanks, covering the approaches to forts Éguillette and Balaguier. Buonaparte complained to Saliceti and Gasparin that his hopes of a quick victory had been scuppered; now he would have to take Fort Mulgrave before he could get at the key positions, and that would take time. He carried on building up his batteries and stores of shot and powder, ignoring orders from Carteaux, who complained but could do nothing as Buonaparte had the ear of the representatives of the government. Saliceti passed Buonaparte’s criticisms of Carteaux to his colleagues in Marseille, Paul Barras, Stanislas Fréron and Jean-François Ricord, who wrote to Paris recommending that Carteaux be replaced and Buonaparte promoted. On 18 October he received his nomination as chef de bataillon, equivalent to the rank of major, and five days later Carteaux was removed from his command.

Buonaparte had become adept at disregarding his superiors and bypassing their instructions without giving offence, employing flattery where necessary. He also knew when to force the issue and to intimidate in order to have his way. Saliceti was now permanently at headquarters in Ollioules, and backed him up. Napoleone nevertheless had to tread carefully, as the waves of terror rippling out from Paris led people to denounce others for treason as a means of avoiding being denounced themselves, and with many officers defecting to the enemy the nobleman Buonaparte was not beyond suspicion. He nevertheless did stick his neck out to protect his former superior in the regiment of La Fère, Jean-Jacques Gassendi, who had been arrested, by insisting he needed him to organise an artillery arsenal in Marseille.10

Carteaux’s command had been given to the hardly more martial General François Doppet, a physician who dabbled in literature, and had only won high rank by finding himself in the right place at the right time. But on 15 November his nerve failed during an attack on Fort Mulgrave: he gave the order to retreat when he saw the English making a sortie, only to have a furious Buonaparte, his face bathed in blood from a light wound, gallop up and call him a jean foutre (the closest English approximation would be ‘fucking idiot’). Doppet took it well. He was aware of his limitations, and realised that chef de bataillon Buonaparte knew his business.11

Buonaparte’s orders and notes during these weeks are succinct and precise, and while their tone is commanding, he takes the trouble to explain why compliance with his demands is essential. In war, as in any other critical situation, people quickly rally to the person who gives the impression of knowing what they are about, and Buonaparte’s self-confidence was magnetic. He showed bravery and steadiness under fire, and did not spare himself, which set him apart from many of the political appointments milling around at headquarters. ‘This young officer,’ wrote General Doppet, ‘combined a rare bravery and the most indefatigable activity with his many talents. Every time I went out on my rounds, I always found him at his post; if he needed a moment’s rest, he took it on the ground, wrapped in his cloak; he was never away from his batteries.’12

Through effort and resourcefulness, Buonaparte had built up an artillery park of nearly a hundred guns and set up a dozen batteries, provided the necessary powder and shot, and trained the soldiers to man them. For his chief of staff he had picked the apparently vain and frivolous Jean-Baptiste Muiron, who had trained as an artillery officer and quickly became an enthusiastic aide. In the twenty-six-year-old Félix Chauvet he identified a brilliant commissary who earned and returned his affection as well as serving him efficiently. During an attack on one of the batteries, Buonaparte had noticed the engaging bravery under fire of a young grenadier in the battalion of the Côte d’Or named Andoche Junot. When he saw that the man also had beautiful handwriting he appropriated him as an aide, only to discover that he had trained for the artillery in the school at Châlons. A couple of weeks later, another young man joined Buonaparte’s entourage. He was the handsome nineteen-year-old Auguste Marmont, a cousin of Le Lieur de Ville sur Arce, who had trained for the artillery at Châlons with Junot.13

On 16 November a new commander arrived to take over from Doppet. He was General Jacques Dugommier, a fifty-five-year-old professional soldier, a veteran of the Seven Years’ War and the American War of Independence who knew how to call the troops to order. He had brought General du Teil and a couple of artillery officers with him, but quickly realised that Buonaparte had the situation in hand, and he did little more than endorse his decisions. ‘I can find no words to describe the merits of Buonaparte,’ he wrote to the minister of war. ‘Much technical knowledge, as much intelligence and too much bravery is only a faint sketch of the qualities of this uncommon officer.’14

On 25 November Dugommier held a council of war, attended by Saliceti and, in place of Gasparin, who had died, a newly-arrived représentant, Augustin Robespierre, younger brother of one of the leading lights of the Committee of Public Safety. They considered Dugommier’s plan, then that drawn up in Paris by Carnot. Both involved multiple attacks. Buonaparte argued that this would disperse their forces, and put forward his own plan, which consisted of a couple of feint attacks and a massive assault on forts Mulgrave, Éguillette and Balaguier, whose capture he was confident would precipitate a rapid evacuation of Hood’s fleet and the fall of the city. The plan was accepted and preparations put in hand.15

On 30 November the British commander in Toulon, General O’Hara, made a sortie and succeeded in capturing a battery and spiking its guns before moving on Ollioules. Dugommier and Saliceti managed to rally the fleeing republican forces and lead up reinforcements. They retook the battery, a battalion led by Louis-Gabriel Suchet taking O’Hara prisoner in the process, and Buonaparte unspiked the guns and opened up on the fleeing allies. He had been in the thick of the fighting and earned a mention in Dugommier’s despatch to Paris.16

The day’s fighting had nevertheless demonstrated the lack of mettle and experience of the French troops. The worsening weather combined with food shortages to sap morale. Despairing of their ability to take Toulon, Barras and Fréron considered raising the siege and taking winter quarters. Saliceti pressed Dugommier to attack, but the general hesitated, as a failed assault might cost him his head. As it was, they were being accused in Paris of lack of zeal and of living in luxury.17

Dugommier resolved to act on Buonaparte’s plan, and the batteries facing Fort Mulgrave began bombarding it on 14 December. The British batteries responded vigorously, and Buonaparte was thrown to the ground by the wind of a passing shot. The attack, by a force of 7,000 men in three columns, began at 1 a.m. on 17 December. A storm had broken and Dugommier hesitated, but Buonaparte pointed out that the conditions might actually prove favourable, and the impatience of Saliceti carried the day. The French infantry went into action in pouring rain, the darkness lit up by flashes of lightning, the sound of the guns drowned out by peals of thunder. Two of the advancing columns strayed from their prescribed route and lost cohesion as many of the soldiers fell back or fled. Other units reached Fort Mulgrave and began escalading its defences. The fighting was fierce – the attack on the fort would cost the French over a thousand casualties – but Muiron eventually forced his way into the fort, closely followed by Dugommier and Buonaparte, who had his horse shot under him at the beginning of the attack, and was wounded in the leg by an English corporal’s lance as he stormed the ramparts.

As soon as he had taken possession of the fort, Buonaparte turned its guns on those of forts Éguillette and Balaguier, and ordered Marmont to start bombarding them. The British mounted a counter-attack, but it was repulsed and they were forced to evacuate the two remaining forts. By then it was light, and Buonaparte began firing incendiary shells and red-hot cannonballs at the nearest British ships, blowing up two. He told anyone who would listen that the battle was over and Toulon was theirs, but Dugommier, Robespierre, Saliceti and others were sceptical, believing the town would only fall after a few more days’ fighting. They were wrong – the explosions of the two ships were a signal the allies could not ignore, and that morning they decided to evacuate; they began moving men out while the ships struggled in a strong wind to pull out of range of the French guns.

The evacuation proceeded through that day and the next, with the allies towing away nine French warships and blowing up a further twelve, setting fire to ships’ stores and the arsenal, and taking on board thousands of French royalists. Anyone who could get hold of a boat was rowing out to the allied ships, and some even tried swimming. They were under constant fire from batteries newly set up by Buonaparte on the promontory and the heights above the city. That night the burning ships lit up the scene, revealing what Buonaparte described as ‘a sublime but heart-rending sight’.18

The French entered the city on the morning of 19 December, looting, raping and lynching anyone they pleased to label as an enemy of the Revolution. On the quayside people were throwing themselves into the water to reach the departing British ships. Those who did not drown were subjected to the fury of the republican soldiery. Over two decades later, Buonaparte recalled the revulsion he had felt at the sight, and according to some sources he managed to save a number of lives.19

Barras, Saliceti, Ricord, Robespierre and Fréron carried out a purge of the population of Toulon. ‘The national vengeance has been unfurled,’ they proclaimed, listing those categories which had been ‘exterminated’. Barras suggested it would be simpler if they removed all those who were proven ‘patriots’, that is to say revolutionaries, and killed all the rest. The population of the city, which would be renamed Port-de-la-Montagne, fell from 30,000 to 7,000.20

On 22 December 1793 Buonaparte was promoted to the rank of brigadier general. He was only twenty-four years old, but this did not make him an exception. Over 6,000 officers of all arms had emigrated since 1791, and another 10,000 would have done so by the summer of 1794. Generals and higher-ranking officers were guillotined by the hundred as suspected traitors. In consequence, the Republic had been obliged to nominate no fewer than 962 new generals between 1791 and 1793. But in the case of Buonaparte, the promotion was merited, and he knew it.21

‘I told you we would be brilliantly successful, and, you see, I keep my word,’ he wrote banteringly from Ollioules to the deputy minister of war in Paris on 24 December, using the familiar ‘tu’ form, no doubt to stress his revolutionary attitude. He had already noted that in the current climate the story that was told first was the one that stuck in the mind, and he informed the minister that thanks to his action, the British had been prevented from burning any of the French ships or naval stores, which was a blatant lie.22

He had proved not only that he was a capable and resourceful officer, but also that he was a leader of men. He had won the admiration of all the real soldiers present, starting with Dugommier. More than that, he had revealed a charisma that many of his young comrades found hard to resist.23

‘He was small in stature, but well proportioned, thin and puny in appearance but taut and strong,’ noted Claude Victor (another who had distinguished himself at Toulon and had also been made a general), noting that ‘his features had an unusual nobility’ and his eyes seemed to send out shafts of fire. His gravity and sense of purpose impressed those around him. ‘There was mystery in the man,’ Victor felt.24

Buonaparte was exhausted. Three months of intense activity, poor diet, frequent nights spent sleeping on the ground wrapped only in his cloak, and that during the winter months, must have placed a heavy strain on his constitution. He had a deep flesh wound and had also caught scabies, which was then endemic in the army. That may be why, at a moment when he could have obtained a posting to one of the armies actively engaged against the enemy, he was content to accept that of inspector of the coastal defences along the stretch between Toulon and Marseille. Another reason may have been a desire to lie low. He had seen how easily people could lose their commands, and he had probably made a number of enemies.25

It may just have been that he wished to be close to his family, which had moved further away from Toulon, first to Beausset, then Brignoles and finally Marseille, where he joined them on 2 January 1794. His general’s pay of 12,000 livres plus expenses would have been welcome, as the cost of living had risen dramatically in the course of 1793. The family had lived through lean times, with Letizia taking in washing, and the daughters, as gossip had it, resorting to prostitution. Maria Paolina, now Paulette, who had grown into a rare beauty, had been caught stealing figs from a neighbour’s garden.26

8

Adolescent Loves

Buonaparte spent the first weeks of 1794 travelling up and down the coast inspecting the defences and issuing quantities of crisp instructions. These go into minute detail on the exact quantities of powder and shot required, which spare parts should be assembled, and even the manner in which horses should be harnessed for specific tasks.

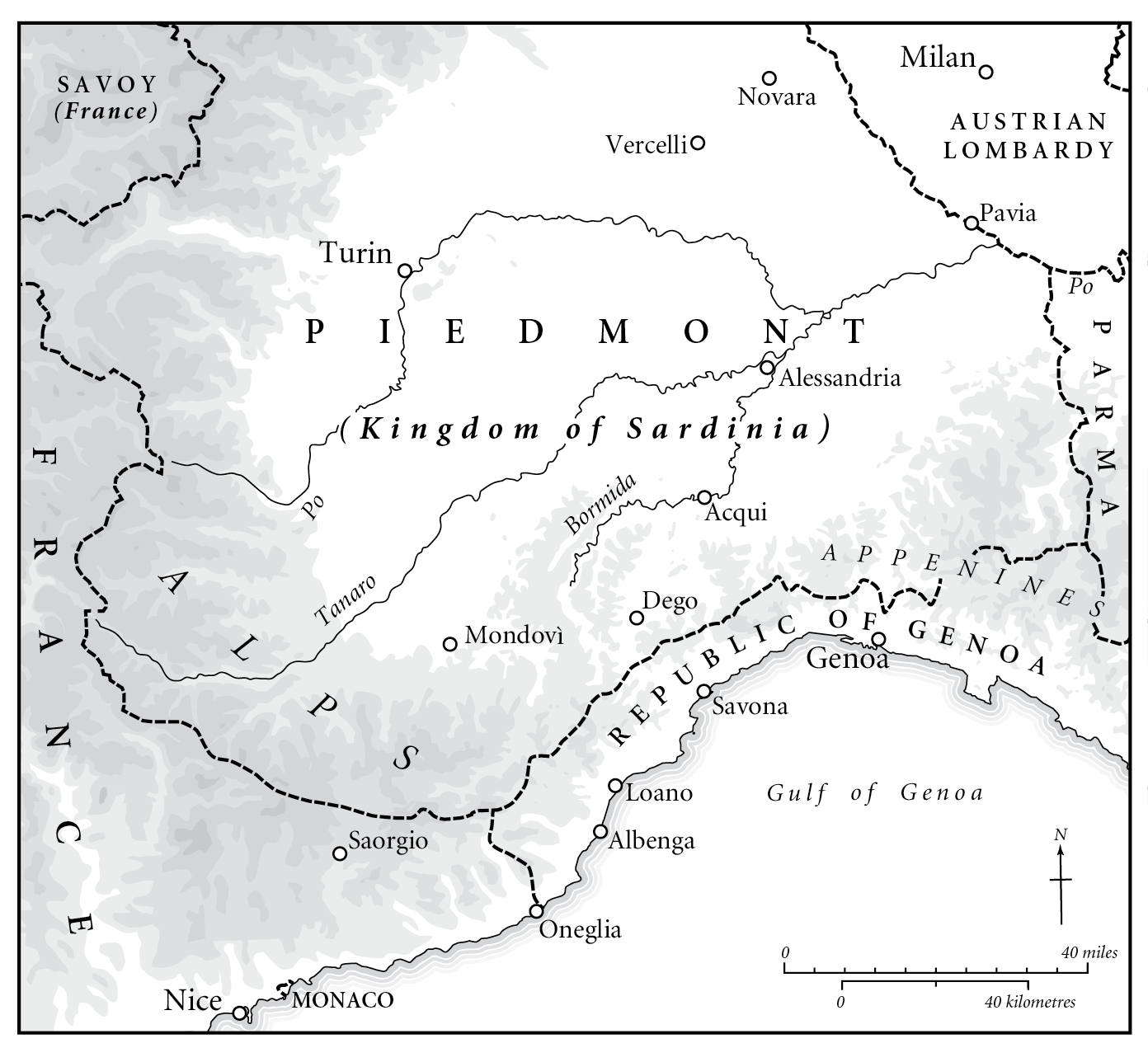

At the beginning of February he was appointed to command the artillery of the Army of Italy, operating against the forces of the King of Sardinia. They had invaded southern France in 1792 but were driven back, following which Savoy and Nice had been incorporated into the French Republic, but they still held the Alpine passes, from which they threatened to recover the lost provinces. The port of Oneglia, a Sardinian enclave in the territory of the neutral Republic of Genoa and the chief link between the king’s island and mainland provinces, was also considered a threat, since it resupplied British warships and harboured corsairs who preyed on French shipping.

Buonaparte’s new salary allowed him to install his family in the comfortable if modest Château-Sallé outside Antibes, not far from his headquarters in Nice. Joseph, whose job as commissary had awakened an interest in trade and speculation, was currently in Nice too, exploring business opportunities. Lucien was at Saint-Maximin, where as head of its Jacobin club he had changed the town’s name to ‘Marathon’, in homage as much to the ‘martyr of the Revolution’ Jean-Paul Marat, who had been assassinated in his bath by the royalist Charlotte Corday, as to the heroic ancient Greek defenders of their homeland. He had also changed his own name, to ‘Brutus’, and had married Christine Boyer, the sister of the keeper of the inn at which he lodged.1

The commander of the Army of Italy was General Pierre Dumerbion, a sixty-year-old professional. He was supervised by the political commissioners Saliceti, Augustin Robespierre and Ricord, who commissioned Buonaparte to prepare a campaign plan. As the Sardinian positions in the mountains were almost unassailable, he suggested ignoring them and striking at their bases: their left wing on the lower ground nearer the sea was vulnerable, and if the French could break through there, they would be able to sweep into the enemy rear. His plan was accepted, and operations began on 7 April, spearheaded by General André Masséna, who captured Oneglia two days later, and by the end of the month the French were in Saorgio, strategic gateway into Piedmont.

Buonaparte’s role consisted of ensuring the artillery was in position and adequately supplied. To assist him he had selected two old comrades from the regiment of La Fère, Nicolas-Marie Songis and Gassendi, his new companions Marmont and Muiron, and as aides-de-camp Junot and his own younger brother Louis. By 1 May he was back in Nice, drawing up further plans which would have taken the French into the plain of Mondovi, but the operations were halted by the war minister Lazare Carnot, who was against involving French forces any deeper in Italy. The Midi was still politically unstable, and there might be unrest if the army moved off. Carnot also needed all available troops to roll back the Spanish invasion.

Buonaparte composed a memorandum for the Committee of Public Safety giving a strategic overview of France’s military position. He argued that invading Spain would yield no tangible benefits, while invading Piedmont would result in the overthrow of a throne that would always be inimical to the French Republic. More important, it would make it possible to defeat Austria, which would only make peace if Vienna were threatened by a two-pronged attack, through Germany in the north and Italy in the south. Austria, he argued, was the cornerstone of the coalition against France, and if it were knocked out that would fall apart.2

Robespierre suggested that Buonaparte accompany him to Paris. The two men had grown close over the past four months, drawn together by the zeal with which they approached their respective tasks and by the shared conviction of the need for strong central authority. Under the dominant influence of Robespierre’s elder brother Maximilien, the Committee of Public Safety in Paris was exercising just such authority, through a reign of Terror which sent thousands to the guillotine. But Robespierre’s grip on power was weakening, and Augustin’s suggestion that Buonaparte come to Paris might have had something to do with that: he allegedly suggested placing him in command of the Paris National Guard.3

Buonaparte briefly considered the proposal, and according to Lucien discussed it with his brothers before deciding against it. To Ricord he admitted a reluctance to get involved in revolutionary politics, and his instinct was to stay at his post with the army. Whether the fact that he was also having an affair with Ricord’s wife Marguerite had any bearing on his decision is unclear.4

At the beginning of July he was sent by Saliceti to Genoa to assess the intentions of the city’s government, which was neutral but under pressure from the anti-French coalition, and to inspect its defences for future reference. He left on 11 July, accompanied by Junot, Marmont and Louis, as well as Ricord, but was back at Nice by the end of the month. Yet he was too busy to attend the wedding of his brother Joseph on 1 August.5

Joseph’s bride, Marie-Julie Clary, was twenty-two years old, not pretty, but pious, honest, generous, dutiful, family-minded, intelligent and rich. She came from a family of Marseille merchants with extensive interests in the ports of the eastern Mediterranean, and she brought him a considerable dowry. With this under his belt, Joseph’s bearing changed, and he now assumed a gravitas he felt appropriate as head of the family.6

Buonaparte was still at headquarters when, on 4 August, news reached him of the coup in Paris which had toppled Robespierre on 27 July – 9 Thermidor in the revolutionary calendar. He was deeply affected by the misfortune of his friend, who was guillotined along with his brother the following day. And he did not have to wait long to be arrested himself.7

As soon as he heard of the fall of Robespierre, Saliceti wrote to the Committee of Public Safety accusing Augustin Robespierre, Ricord and ‘their man’ Buonaparte of having sabotaged the operations of the Army of Italy and conspired against the Republic with the allies and with Genoa, whose authorities had bribed Buonaparte with ‘a million’ (the currency was not specified). He ordered the arrest of Buonaparte and the seizure of his papers prior to his being sent to Paris to answer charges of treason.8

It is not clear whether Buonaparte was actually put in gaol or merely under house arrest. Junot managed to pass a note to him offering to arrange his escape, but Buonaparte refused. ‘I recognise your friendship in your proposal, my dear Junot; and you well know that which I have vowed you and on which you know you may count,’ he wrote back. But he was confident his innocence would be recognised and urged Junot to do nothing, as this could only compromise him. Innocence was no guarantor of safety under revolutionary conditions, but Buonaparte was lucky. Saliceti’s accusation had been no more than a reflex of self-preservation, and as soon as he felt he was in the clear he sent another letter to Paris stating that examination of the general’s papers had yielded no evidence of treason, and, bearing in mind his usefulness for the Army of Italy, he and his colleagues had ordered his provisional release. Nobody apart from Junot seems to have taken the charges against Buonaparte seriously. His landlord Joseph Laurenti, with whose daughter Buonaparte was carrying on a flirtation, had stood bail, and as a result he spent most of the eleven days of his detention in his own lodgings.9

Meanwhile, the Austrians had sent an army to reinforce the Sardinian forces, and General Dumerbion felt he had to do something. ‘My child,’ he wrote to Buonaparte, ‘draw me up a campaign plan as only you know how.’ On 26 August the child handed him one, and on 5 September he was at Oneglia to implement it. The French forces advanced on the point at which the two enemy armies met, aiming to split them apart. On 21 September Buonaparte witnessed his first pitched battle, an attack on Dego in which General Masséna distinguished himself. But further operations were called off by Carnot in Paris, and Buonaparte was left with nothing to do. This should have been welcome to him.10