Полная версия

Napoleon

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2018

Copyright © Adam Zamoyski 2018

Cover photograph © Getty Images

Adam Zamoyski asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Maps by Martin Brown

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008116095

Ebook Edition © October 2018 ISBN: 9780008116088

Version: 2019-08-03

Dedication

In memory

of

GILLON AITKEN

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

List of Illustrations

List of Maps

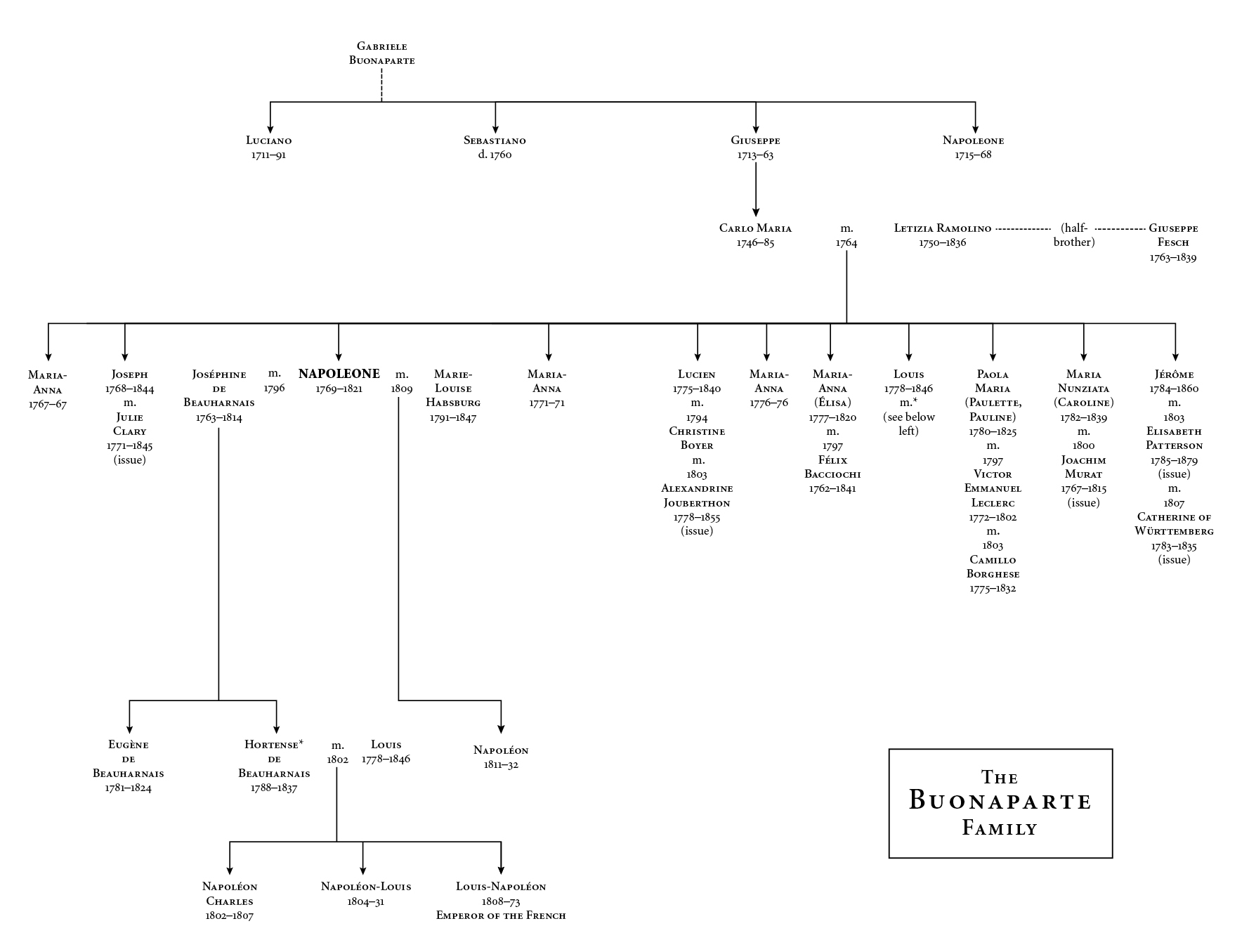

Family Tree

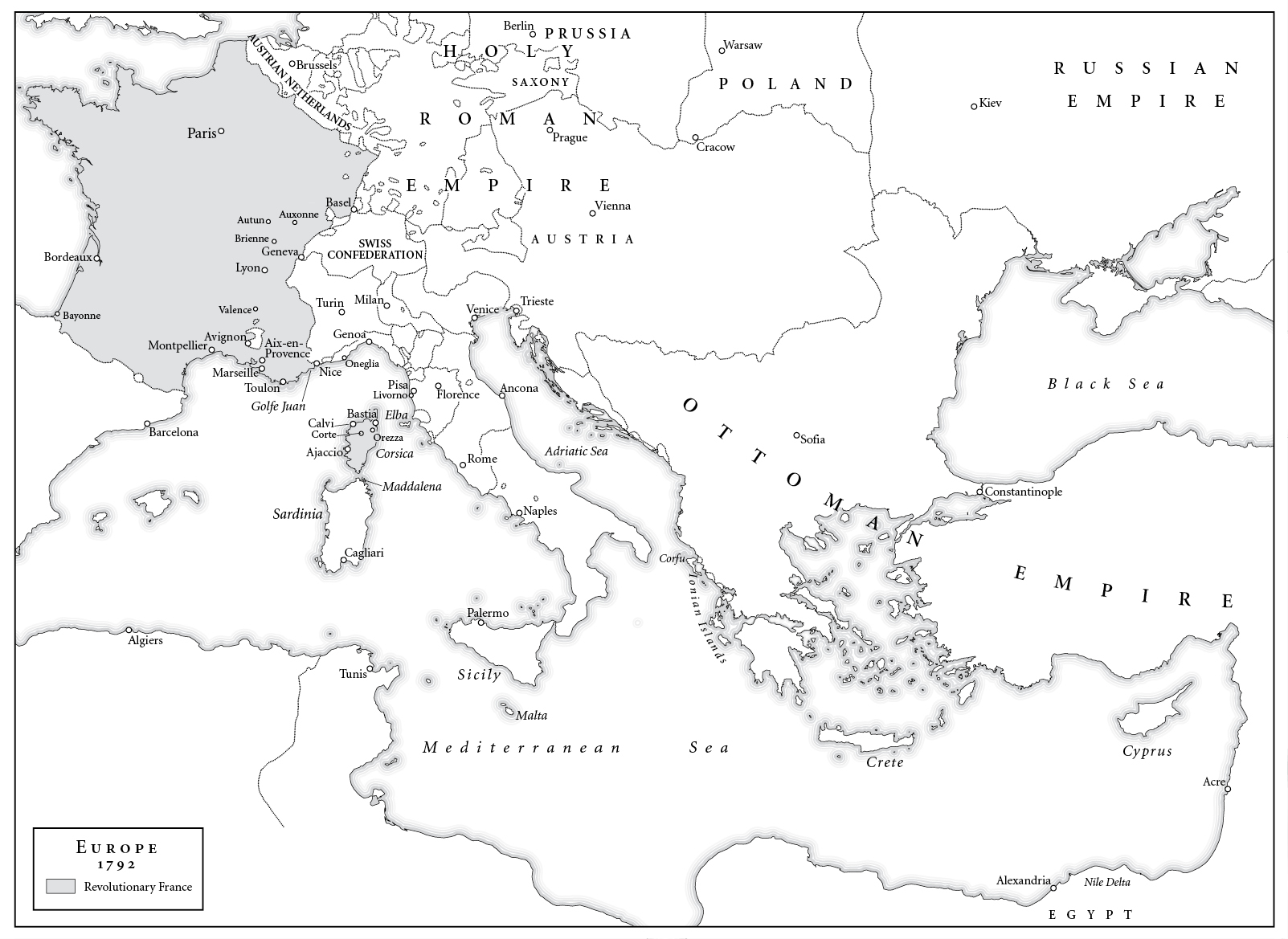

Map

Preface

1 A Reluctant Messiah

2 Insular Dreams

3 Boy Soldier

4 Freedom

5 Corsica

6 France or Corsica

7 The Jacobin

8 Adolescent Loves

9 General Vendémiaire

10 Italy

11 Lodi

12 Victory and Legend

13 Master of Italy

14 Eastern Promise

15 Egypt

16 Plague

17 The Saviour

18 Fog

19 The Consul

20 Consolidation

21 Marengo

22 Caesar

23 Peace

24 The Liberator of Europe

25 His Consular Majesty

26 Towards Empire

27 Napoleon I

28 Austerlitz

29 The Emperor of the West

30 Master of Europe

31 The Sun Emperor

32 The Emperor of the East

33 The Cost of Power

34 Apotheosis

35 Apogee

36 Blinding Power

37 The Rubicon

38 Nemesis

39 Hollow Victories

40 Last Chance

41 The Wounded Lion

42 Rejection

43 The Outlaw

44 A Crown of Thorns

Notes

Picture Section

Bibliography

Index

Also by Adam Zamoyski

About the Author

About the Publisher

Illustrations

Napoleon’s mother Letizia Bonaparte in 1800, by Jean-Baptiste Greuze. (Granger Historical Picture Archive/Alamy Stock Photo)

Two sketches of Bonaparte by Jacques-Louis David. (Sketches of Napoleon Bonaparte, 1797 (pencil), David, Jacques-Louis (1748–1825)/Musée d’Art et d’Histoire, Palais Massena, Nice, France/Bridgeman Images)

Bonaparte during the Italian campaign of 1796, by Giuseppe Longhi. (Paul Fearn/Alamy Stock Photo)

Bonaparte leading his troops across the bridge at Arcole, by Antoine-Jean Gros. (Photo by Universal History Archive/Getty Images)

Bonaparte in 1797, by Francesco Cossia. (Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

Josephine Bonaparte in 1797, by Andrea Appiani. (ART Collection/Alamy Stock Photo)

Auguste Marmont, by Georges Rouget. (Wikimedia Commons)

Andoche Junot, by David. (© President and Fellows of Harvard College)

Joachim Murat. (ART Collection/Alamy Stock Photo)

Josephine’s son Eugène de Beauharnais, by Gros. (Hirarchivum Press/Alamy Stock Photo)

Napoleon’s younger sister Pauline, by Jean Jacques Thérésa de Lusse. (flickr/lost gallery/Pauline Bonaparte, Princess Borghese/De Lusse/CC by 2.0)

Bonaparte visiting plague victims at Jaffa during his Syrian campaign, by Gros. (Photo by Archiv Gerstenberg/ullstein bild via Getty Images)

Joseph Bonaparte. (Photo by Stefano Bianchetti/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)

Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte, by Nicolas Joseph Jouy. (Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo)

Napoleon’s younger brother Lucien, by François-Xavier Fabre, c.1808. (ART Collection/Alamy Stock Photo)

Bonaparte in 1800, by Louis Léopold Boilly. (Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821) Premier Consul (oil on canvas), Boilly, Louis Léopold (1761–1845)/Private Collection/Archives Charmet/Bridgeman Images)

The house in the rue de la Victoire. (Photo 12/Alamy Stock Photo)

The Tuileries, c.1860. (Photo by LL/Roger Viollet/Getty Images)

Jean-Jacques-Régis Cambacérès, by Greuze, 1805. (Cambacérès/Photo © CCI/Bridgeman Images)

Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand in 1804, by David. (Photo Josse/Leemage/Corbis via Getty Images)

Joseph Fouché. (Portrait of Joseph Fouché (1759–1820) Duke of Otranto, 1813 (oil on canvas), French School, (19th century)/Château de Versailles, France/Bridgeman Images)

Josephine’s daughter Hortense de Beauharnais, by François Gérard. (Paul Fearn/Alamy Stock Photo)

The Château of Malmaison, by Henri Courvoisier-Voisin. (Photo Josse/Leemage/Corbis via Getty Images)

Napoleon’s younger brother Louis in 1809, by Charles Howard Hodges. (Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

Napoleon crossing the Alps in 1802, by David. (Photo by GraphicaArtis/Getty Images)

The Emperor Napoleon I in 1805, by David. (Photo Josse/Leemage/Corbis via Getty Images)

A fragment of David’s painting of the coronation, showing Joseph, Louis, Napoleon’s three sisters, Hortense and her son Napoléon-Charles. (Photo Josse/Leemage/Corbis via Getty Images)

Napoleon’s youngest brother Jérôme, 1805. (Courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society, xx.5.52)

Napoleon at Eylau, by Gros (Photo by Universal History Archive/Getty Images)

Marshal Jean Lannes, by Gérard. (Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

General Armand de Caulaincourt, sketched in 1805 by David. (Portrait of Armand Augustin Louis. Marquis de Caulaincourt (1772–1827) (pencil on paper) (b/w photo), David, Jacques Louis (1748–1825)/Musée des Beaux-Arts, Besancon, France/Bridgeman Images)

General Géraud-Christophe Duroc, by Anne-Louis Girodet-Trioson. (Portrait of Duroc, Grand Marshal of the Palace (oil on canvas), Girodet de Roucy-Trioson, Anne Louis (1767–1824)/Musée Bonnat, Bayonne, France/Bridgeman Images)

Napoleon I in 1806, by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. (Photo Josse/Leemage/Corbis via Getty Images)

View of the proposed palace for the King of Rome, by Pierre-François Fontaine. (From Projets d’architecture, plan number 32, France, 19th century/De Agostini Picture Library/Bridgeman Images)

Napoleon en famille, by Alexandre Menjaud. (Napoleon I (1769–1821), Marie Louise (1791–1847) and the King of Rome (1811–73) 1812 (oil on canvas), Menjaud, Alexandre (1773–1832)/Château de Versailles, France/Bridgeman Images)

Napoleon in early 1812, by David. (Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Napoleon on the bridge of HMS Bellerophon, by Charles Lock Eastlake, 1815. (Granger Historical Picture Archive/Alamy Stock Photo)

The house at Longwood on St Helena, where Napoleon spent his last years. (Photo by The Print Collector/Getty Images)

Napoleon on St Helena, 1820. (Paul Fearn/Alamy Stock Photo)

Maps

Europe in 1792

Toulon

The Italian theatre

Montenotte

Lodi

The pursuit

Castiglione

Würmser outmanoeuvred

Arcole

Rivoli

The march on Vienna

The settlement of Campo Formio

Egypt

Europe in 1800

Marengo

Ulm

Austerlitz

The campaigns of 1806–07

Europe in 1808

Aspern–Essling

Wagram

Europe in 1812

The invasion of Russia

Borodino

The Berezina

The Saxon campaign, 1813

The defence of France in 1814

The Waterloo campaign

Family Tree

Map

Preface

A Polish home, English schools, and holidays with French cousins exposed me from an early age to violently conflicting visions of Napoleon – as godlike genius, Romantic avatar, evil monster or just nasty little dictator. In this crossfire of fantasy and prejudice I developed an empathy with each of these views without being able to agree with any of them.

Napoleon was a man, and while I understand how others have done, I can see nothing superhuman about him. Although he did exhibit some extraordinary qualities, he was in many ways a very ordinary man. I find it difficult to credit genius to someone who, for all his many triumphs, presided over the worst (and entirely self-inflicted) disaster in military history and single-handedly destroyed the great enterprise he and others had toiled so hard to construct. He was undoubtedly a brilliant tactician, as one would expect of a clever operator from a small-town background. But he was no strategist, as his miserable end attests.

Nor was Napoleon an evil monster. He could be as selfish and violent as the next man, but there is no evidence of him wishing to inflict suffering gratuitously. His motives were on the whole praiseworthy, and his ambition no greater than that of contemporaries such as Alexander I of Russia, Wellington, Nelson, Metternich, Blücher, Bernadotte and many more. What made his ambition so exceptional was the scope it was accorded by circumstance.

On hearing the news of his death, the Austrian dramatist Franz Grillparzer wrote a poem on the subject. He had been a student in Vienna when Napoleon bombarded the city in 1809, so he had no reason to like him, but in the poem he admits that while he cannot love him, he cannot bring himself to hate him; according to Grillparzer, Napoleon was but the visible symptom of the sickness of the times, and as such bore the blame for the sins of all. There is much truth in this view.1

In the half-century before Napoleon came to power, a titanic struggle for dominion saw the British acquire Canada, large swathes of India, a string of colonies, and aspire to lay down the law at sea; Austria grab provinces in Italy and Poland; Prussia increase in size by two-thirds; and Russia push her frontier 600 kilometres into Europe and occupy large areas of Central Asia, Siberia and Alaska, laying claims as far afield as California. Yet George III, Maria Theresa, Frederick William II and Catherine II are not generally accused of being megalomaniac monsters and compulsive warmongers.

Napoleon is frequently condemned for his invasion of Egypt, while the British occupation which followed, designed to guarantee colonial monopoly over India, is not. He is regularly blamed for re-establishing slavery in Martinique, while Britain applied it in its colonies for a further thirty years, and every other colonial power for several decades after that. His use of police surveillance and censorship is also regularly reproved, even though every other state in Europe emulated him, with varying degrees of discretion or hypocrisy.

The tone was set by the victors of 1815, who arrogated the role of defenders of a supposedly righteous social order against evil, and writing on Napoleon has been bedevilled ever since by a moral dimension, which has entailed an imperative to slander or glorify. Beginning with Stendhal, who claimed he could only write of Napoleon in religious terms, and no doubt inspired by Goethe, who saw his life as ‘that of a demi-god’, French and other European historians have struggled to keep the numinous out of their work, and even today it is tinged by a sense of awe. Until very recently, Anglo-Saxon historians have shown reluctance to allow an understanding of the spirit of the times to help them see Napoleon as anything other than an alien monster. Rival national mythologies have added layers of prejudice which many find hard to overcome.2

Napoleon was in every sense the product of his times; he was in many ways the embodiment of his epoch. If one wishes to gain an understanding of him and what he was about, one has to place him in context. This requires ruthless jettisoning of received opinion and nationalist prejudice, and dispassionate examination of what the seismic conditions of his times threatened and offered.

In the 1790s Napoleon entered a world at war, and one in which the very basis of human society was being questioned. It was a struggle for supremacy and survival in which every state on the Continent acted out of self-interest, breaking treaties and betraying allies shamelessly. Monarchs, statesmen and commanders on all sides displayed similar levels of fearful aggression, greed, callousness and brutality. To ascribe to any of the states involved a morally superior role is ahistorical humbug, and to condemn the lust for power is to deny human nature and political necessity.

For Aristotle power was, along with wealth and friendship, one of the essential components of individual happiness. For Hobbes, the urge to acquire it was not only innate but beneficent, as it led men to dominate and therefore organise communities, and no social organisation of any form could exist without the power of one or more individuals to order others.

Napoleon did not start the war that broke out in 1792 when he was a mere lieutenant and continued, with one brief interruption, until 1814. Which side was responsible for the outbreak and for the continuing hostilities is fruitlessly debatable, since responsibility cannot be laid squarely on one side or the other. The fighting cost lives, for which responsibility is often heaped on Napoleon, which is absurd, as all the belligerents must share the blame. And he was not as profligate with the lives of his own soldiers as some.

French losses in the seven years of revolutionary government (1792–99) are estimated at four to five hundred thousand; those during the fifteen years of Napoleon’s rule at just under twice as high, at eight to nine hundred thousand. Given that these figures include not only dead, wounded and sick, but also those reported as missing, whose numbers went up dramatically as his ventures took the armies further afield, it is clear that battle losses were lower under Napoleon than during the revolutionary period – despite the increasing use of heavy artillery and the greater size of the armies. The majority of those classed as missing were deserters who either drifted back home or settled in other countries. This is not to diminish the suffering or the trauma of the war, but to put it in perspective.3

My aim in this book is not to justify or condemn, but to piece together the life of the man born Napoleone Buonaparte, and to examine how he became ‘Napoleon’ and achieved what he did, and how it came about that he undid it.

In order to do so I have concentrated on verifiable primary sources, treating with caution the memoirs of those such as Bourrienne, Fouché, Barras and others who wrote principally to justify themselves or to tailor their own image, and have avoided using as evidence those of the duchesse d’Abrantès, which were written years after the events by her lover the novelist Balzac. I also ignore the various anecdotes regarding Napoleon’s birth and childhood, believing that it is immaterial as well as unprovable that he cried or not when he was born, that he liked playing with swords and drums as a child, had a childhood crush on some little girl, or that a comet was sighted at his birth and death. There are quite enough solid facts to deal with.

I have devoted more space in relative terms to Napoleon’s formative years than to his time in power, as I believe they hold the key to understanding his extraordinary trajectory. As I consider the military aspects only insofar as they produced an effect, on him and his career or the international situation, the reader will find my coverage very uneven. I give prominence to the first Italian campaign because it demonstrates the ways in which Napoleon was superior to his enemies and colleagues, and because it turned him into an exceptional being, both in his own eyes and those of others. Subsequent battles are of interest primarily for the use he made of them, while the Russian campaign is seminal to his decline and reveals the confusion in his mind which led to his political suicide. To those who would like to learn more about the battles I would recommend Andrew Roberts’s masterful Napoleon the Great. The battle maps in the text are similarly spare, and do not pretend to accuracy; they are designed to illustrate the essence of the action.

The subject is so vast that anyone attempting a life of Napoleon must necessarily rely on the work of many who have trawled through archives and on published sources. I feel hugely indebted to all those involved in the Fondation Napoléon’s new edition of Napoleon’s correspondence. I also owe a great deal to the work done over the past two decades by French historians in debunking the myths that have gained the status of truth and excising the carbuncles that have overgrown the verifiable facts during the past two centuries. Thierry Lentz and Jean Tulard stand out in this respect, but Pierre Branda, Jean Defranceschi, Patrice Gueniffey, Annie Jourdan, Aurélien Lignereux and Michel Vergé-Franceschi have also helped to blow away cobwebs and enlighten. Among Anglo-Saxon historians, Philip Dwyer has my gratitude for his brilliant work on Napoleon as propagandist, and Munro Price for his invaluable archival research on the last phase of his reign. The work of Michael Broers and Steven Englund is also noteworthy.

I owe a debt of thanks to Olivier Varlan for bibliographic guidance, and particularly for having let me see Caulaincourt’s manuscript on the Prussian and Russian campaigns of 1806–07; to Vincenz Hoppe for seeking out sources in Germany; to Hubert Czyżewski for assisting me in unearthing obscure sources in Polish libraries; to Laetitia Oppenheim for doing the same for me in France; to Carlo De Luca for alerting me to the existence of the diary of Giuseppe Mallardi; and to Angelika von Hase for helping me with German sources. I also owe thanks to Shervie Price for reading the typescript, and to the incomparable Robert Lacey for his sensitive editing.

Although at times I felt like cursing him, I would like to thank Detlef Felken for his implicit faith in suggesting I write this book, and Clare Alexander and Arabella Pike for their support. Finally, I must thank my wife Emma for putting up with me and encouraging me throughout what has been a challenging task.

Adam Zamoyski

1

A Reluctant Messiah

At noon on 10 December 1797 a thunderous discharge from a battery of guns echoed across Paris, opening yet another of the many grandiose festivals for which the French Revolution was so notable.

Although the day was cold and grey, crowds had been gathering around the Luxembourg Palace, the seat of the Executive Directory which governed France, and according to the Prussian diplomat Daniel von Sandoz-Rollin, ‘never had the cheering sounded more enthusiastic’. People lined the streets leading up to the palace in the hope of catching a glimpse of the hero of the day. But his reticence defeated them. At around ten o’clock that morning he had left his modest house on the rue Chantereine with one of the Directors who had come to fetch him in a cab. As it trundled through the streets, followed by several officers on horseback, he sat well back, seeming in the words of one English witness ‘to shrink from those acclamations which were then the voluntary offering of the heart’.1

They were indeed heartfelt. The people of France were tired after eight years of revolution and political struggle marked by violent lurches to the right or the left. They were sick of the war which had lasted for more than five years and which the Directory seemed unable to end. The man they were cheering, a twenty-eight-year-old general by the name of Bonaparte, had won a string of victories in Italy against France’s principal enemy, Austria, and forced her emperor to come to terms. The relief felt at the prospect of peace and the political stability it was hoped would ensue was accompanied by a subliminal sense of deliverance.

The Revolution which began in 1789 had unleashed boundless hopes of a new era in human affairs. These had been whipped up and manipulated by successive political leaders in a self-perpetuating power struggle, and people longed for someone who could put an end to it. They had read the Bulletins recounting this general’s deeds and his proclamations to the people of Italy, which contrasted sharply with the utterances of those ruling France. Many believed, or just hoped, that the longed-for man had come. The sense of exaltation engendered by the Revolution had been kept alive by overblown festivals, and this one was, according to one witness, as ‘magnifique’ as any.2

The great court of the Luxembourg Palace had been transformed for the occasion. A dais had been erected opposite the entrance, on which stood the indispensable ‘altar of the fatherland’ surmounted by three statues, representing Liberty, Equality and Peace. These were flanked by panoplies of enemy standards captured during the recent campaign, beneath which were placed seats for the five members of the Directory, one for its secretary-general, and more below them for the ministers. Beneath were places for the diplomatic corps, and to either side stretched a great amphitheatre for the members of the two legislative chambers and for the 1,200-strong choir of the Conservatoire. The courtyard was decked with tricolour flags and covered by an awning, turning it into a monumental tent.3