Полная версия

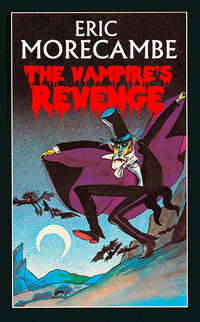

The Vampire’s Revenge

Victor glided towards the trees in order to get away from what he called ‘a cross wind’. He glided rather too quickly and the blustery wind took hold of him, taking him every which way, so much so that as he came into his final approach he had no control at all. He landed, slap, bang, with a heavy wallop into the middle of a large patch of stinging nettles, face down, arms by his side and his legs so crossed that his left leg looked like his right one and vice versa. Everything was wrong and against all the rules he had been taught in the V.A.F. (Vampirian Air Force). His top hat was jammed almost over his eyes, squashing the end of his long nose against his top lip, while his Savile Row flying cloak was wrapped around his neck, almost choking him. He did look a sight.

The scream Victor made when he realised he was in a patch of stinging nettles was so loud that it almost made Areta, inside the presidential house, jump out of her skin. Valentine soothed her by telling her that it would be his parents. Within minutes they were all in the oblong office greeting each other.

Areta watched as Valentine held his mother by the throat as gently and as softly as a breeze, a sure sign of Vampirian affection. Victor also looked on, smiling his approval.

‘What was that noise I heard out there?’ the President asked politely.

‘Who else but your father? He made a terrible landing in a rather large patch of nettles. Lucky for him that your guards were there to help him out. Anyway, it serves him right.’ She looked at her husband as if to say, ‘I love you, but you are a fool.’

Victor thought it was time to defend himself. ‘Ya. It vos the cross vind, it vent across me.’ They all looked at him as he started to scratch and blow on an angry-looking nettle rash.

‘Cross wind, my eye teeth,’ Valeeta said. ‘You are an old fibber,’ she added, with a tiny amount of affection. ‘It was because you are carrying too much weight. Since you retired from being King, you have put on at least a stone and a half in weight. Just look at that belly.’ They all looked where she was pointing and saw a shirt that was stretching over a larger area than it was made for and, here and there, quite a lot of exposed pink tummy, which was beginning to look like expertly blown bubble gum.

‘Vot you are sayink is a lie. Never am I puttink on a stone ant a half in veight, never. An ounce or two, maybe.’

‘An ounce or two, an ounce or two. What rhubarb you talk. Who was it who couldn’t tie his shoelaces when he got up this evening, because he couldn’t bend over? Who had to tie them for him? Me!’ The ex-Queen had a smug look on her face. Victor looked down at his shoes, but he couldn’t see them for his tummy. He looked back at his family and with his eyes asked them all if he was too plump and over-weight. They all nodded with a smile. It was the first time Valentine had smiled that day.

Valentine was the first to broach the subject of Vernon by saying, ‘I’m glad you could both be here. I take it that you have read the papers?’

‘Ve only get the von, The Nightly Express.’

‘Well, that paper carried the story about … you know who.’ He looked away from the old King and Queen. He knew how upset they both must be. After all, Vernon was their son. Valeeta was sitting in a straightbacked chair with her husband standing behind her. They looked very regal.

The Queen was the first to speak, ‘Yes, my dear, we saw the paper and that’s why we are here. We’ve talked it over, your Father and I, and we feel that we would like to help you to … er … get … have … er … Vernon put away for a, well a long time … maybe for ever.’ She was finding it difficult to speak. ‘Or better still, out of the country altogether, deported, I think they call it.’

When the Queen had finished speaking there was a silence. The only movement in the room was Victor, scratching his nettle rash. Valentine walked round the large room before speaking. He stopped and looked directly at the only two parents he had ever known, two Vampires. They had found him and they had reared him. What he was about to say could be hurtful and difficult.

‘I have to be honest with you both. I don’t think that deporting Vernon, or even putting him away for a long time is the right thing to do.’ He held his hand up to stop what was going to be an interruption from the Queen. She stiffened a little, not being used to having to be silent. But, after all, she was an ex-Queen and Valentine was the President. ‘Please let me finish,’ Valentine asked.

‘Ya, let him finish,’ Victor nodded his consent for Valentine to carry on.

‘Thank you, Father. I don’t think putting him away or sending him to another country, well, is really enough. What I’m trying to say,’ he started to speak slowly, ‘what I’m trying to say, or what I think should be done … er, what I’d like to see happen … what I’m trying to say without hurting your feelings, is that I think, well, that maybe we … I think maybe …’

Areta spoke for the first time. She was blunt and went straight to the point that Valentine was finding difficult.

‘He will have to be killed,’ she said in a firm voice. ‘That is what the President was trying to say. Vernon should be killed. We both know that Vernon is your son and you will naturally want to try and help him. I would do the same for my little boy, your grandson. That is understandable. But we all know that Vernon is a maniac and, if something isn’t done, will kill. He would have no compunction in killing you too, or me, or Valentine, or even your grandson … He can’t forgive and he will never forget. A stake must be put through his heart.’ She stopped talking and felt they must all be able to hear her heart beating. She was shaking with fear and anger. Valentine walked over to her.

‘Thank you, darling,’ he said. He then looked at the only parents he had ever had and said, ‘My wife is right. That’s what I was trying to say.’

There was a long silence. No-one moved, even Victor had stopped scratching. It was Victor who broke the silence with a rather loud ‘Ahem’ which he followed with, ‘Ya, maybe you are right.’

The ex-Queen looked more than sternly towards him. He saw the look and said, ‘Maybe not, I don’t know. Vot do you think, mine little crocus?’ He smiled at his wife and scratched the back of his hand. The ex-Queen was much more definite than her husband.

‘He is my son. Mine and Victor’s. For the past three years Victor and I have been very happy living in the country, but our son Vernon, he has suffered; not you, Valentine, nor you, Areta, nor Victor or I, but our own son, Vernon. He was inside that statue for three years. Can you imagine what that must have been like, not being able to move? Only to be able to look at what was going on around him? Never being able to blink, let alone speak?

‘Certainly he won’t forgive and definitely he won’t forget but I will not believe that he would harm, let alone kill, one member of his family. We are his family. We should be out there looking for the poor boy to help him, not just saying “let’s kill him.” That is the easy way. He is part of a dynasty. He comes from a thousand years of Vampires, pure Vampire stock. He is the last of the true Vampires; he should be helped. Have you forgotten what your father did for this country? Have you forgotten what your father did for Igon? He turned him from a twisted, horrible, bent thing into the most handsome of men. That was Vampire magic, great Vampire magic. Magic that took every ounce of strength your poor father had.’

Victor nodded and scratched.

‘I know that both physically and mentally your father is no match for Vernon any more. He gave everything that he could for the benefit of you and this country. Vernon would do the same. I have to agree that something must be done, but I will fight to the end to see that our poor little son is not skewed.1 Where is my poor little boy now? Probably huddled in some dirty old barn crying for his Mummy, me …’ She wiped her eyes, although there were no tears as Vampires can’t and don’t cry. But at that particular moment she was a little confused.

‘I am against the killing of my son Vernon and that is final. Come, Victor, we will try and find our confused and bewildered boy who wouldn’t harm a fly.’

‘Mine dear, I’m agreeink with all you sayink, but can’t ve haff one little drink before ve go, ya?’

‘No, you can’t. You have just started your diet.’

* * *

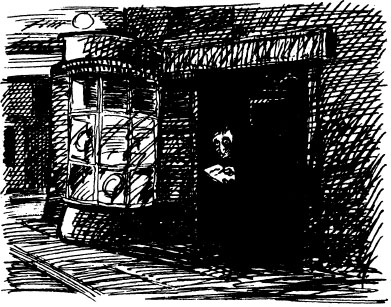

The confused and bewildered little boy was hiding in the doorway of an unlit shop writing in a notebook. He wrote: ‘Igon first, Valentine second, King Victor third and Queen Valeeta fourth. All to be removed, but tortured first. Not necessarily in that order.’

CHAPTER 3

The Inspector tries to clear up the case.

Vernon soon puts him in his place.

Special Prince Igon was on a business trip to Gertcha. Having concluded his business, which was getting Gertcha to buy nuts from Gotcha, he had booked his seat home on the new fancy stage-coach, the Gertcha-Gotcha Flyer. The coach, an eight-seater, pulled by the best six horses from both lands, was the very latest in style and had all the latest safety devices, including disc hooves on the back two horses.

Although the driver and his co-driver sat outside on top of the coach, they shared one enormous hat. It had two skull caps covered with one long piece of material, rather like a plank of wood with two inverted soup bowls. The idea was that it would keep the rain off both of them at the same time.

Inside the coach was a very pretty stewardess serving drinks and duty free tobacco. The trip itself was very quick considering the distance covered; over two hundred miles in just over ten and a half hours, twenty-four horses, a change of driver and co-driver, three stops and four different (but all very pretty) stewardesses, all of whom fell in love with Igon.

Igon sat by the window looking out into the darkness. He had bought his duty free drinks and tobacco, although he didn’t smoke or drink. He had bought them for the old folks’ home on the outskirts of Katchem. He felt sorry for the old folks and had taken them under his wing. He stared into the night, but his thoughts were on the rumours about Vernon and a storm.

‘Have you heard?’ said one passenger to another.

‘Heard what?’ the other passenger asked.

‘What happened in Katchem.’

‘No, what?’

‘They had a storm last night and the statue was blown down.’

Igon was only half listening to the conversation, as he was working out on his portable abacus how much money he had made for his country with his nut deal.

‘What statue?’ the second passenger asked.

‘Just a moment, are you a Gert or a Got?’ the first passenger asked.

‘I’m a Gert,’ the second passenger said with a certain pride.

‘Oh well, in that case you won’t understand,’ the first passenger said, as he continued to play with a multi-coloured cube, trying to get squares of the same colours on each side of the cube.

‘Why won’t I understand?’ asked the second passenger in a small hurt voice.

‘Because you are a Gert and not a Got. If you were a Got, you would understand about the statue.’

‘What should I know about it?’ the second passenger almost begged. ‘It might help me with my business deal in Gotcha.’

‘What business are you doing in Gotcha, then?’ asked the Got man.

‘I’m going there to sell nuts to the Gots,’ the second man said.

‘Why?’ asked the Got man.

‘Because they’ve sold all theirs.’

Igon had started to eavesdrop when he heard the words ‘nuts’ and ‘business’.

‘So please tell me about the statue that’s been blown down?’

‘Well, it’s called the Vernon statue,’ the Got man confided. ‘It was blown down in a storm last night and Vernon wasn’t in it.’ He looked at the Gert man through half a wink and then went back to his cube. The Gert man looked nonplussed.

‘I don’t understand,’ he said. ‘He wasn’t in it?’

‘I said you wouldn’t,’ replied the Got man.

‘Well, may I ask,’ the Gert man said, smiling sarcastically, ‘if, when you put up a statue of someone in Gotcha, do you always put him inside the statue?’

Igon tapped the Got man on the shoulder before he could answer, and asked, ‘Did you say the Vernon statue, the one in Katchem?’

‘Yes,’ the Got man nodded. ‘It blew down last night.’

‘And Vernon was in it?’

‘Are you a Got?’ asked the Got man.

‘Yes,’ replied Igon.

‘No, Vernon wasn’t in it.’

‘Not in it?’ said the incredulous Igon.

The Got man whispered loudly towards Igon, ‘They say he escaped and is after revenge.’ The Got man looked at Igon this time through two half-closed eyes while at the same time nodding slowly.

Meanwhile the Gert man, who had understood not one word of the conversation, thought he would change the subject by asking Igon, ‘What business are you in, young sir?’

‘Nuts,’ Igon replied and after that remark the conversation seemed to peter out.

Igon turned his head back to the window and looked out into the blackness. His eyes focused on the two eyes looking back at him from his own reflection. They were full of fear. As the coach moved along towards Gotcha he felt a shiver run through his body, but it wasn’t a shiver of cold. Igon was frightened, and he knew it. His thoughts were filled with Vernon.

* * *

A new chief inspector of police was brought in to take over the ‘Vernon Problem’ and to make sure that Vernon was caught and punished. His name was Chief Inspector Speekup. Unfortunately he was very deaf, a result of never having dried his ears properly after washing when he was a little boy. At the moment he was busy with the men in the Katchem Police Force, working out how to combat the Vernon Problem. Twenty tall candles had been lit in order, as the Inspector put it, to throw more light on the case. All leave had been cancelled. His team of eight men looked at him with white faces and nervous eyes. He spoke.

‘Men,’ he snapped, as he looked at his eight policemen. ‘We have been chosen.’ He was pressed to perfection in his light brown uniform, his pointed dark brown hat and a cream shoulder cape. He looked like a chocolate cornetto.

‘We have been chosen to apprehend the vicious Vampire, Vernon, and bring him to justice.’

The fear in the men’s eyes grew because they all knew that the Inspector had never caught a criminal in his entire career with the force. He was the joke of the Gotcha police, the joke being, ‘Chief Inspector Speekup couldn’t catch his pants on a nail’. And now here he was after the worst type of criminal, a criminal who had magic on his side, who could escape from anywhere and who couldn’t die unless he was killed in a special way. They all thought the same thing: ‘Fat chance we’ve got of catching Vernon with this fancy-dressed idiot leading us …’

‘And I want him,’ he continued. ‘I want him here in my prison and I want him soon.’ His voice was as dry as a packet of salty crisps. He clicked his heels together.

‘I know what you want,’ was heard quietly from the back line of men. But the Inspector didn’t hear it. He only saw all his men smiling.

‘That’s it, men,’ he said. ‘That’s what I like to see – men who smile in the face of adversity.’ The men began to shuffle their feet. ‘That’s it, men,’ he said again. ‘Keen to get on with it, eh?’

His dry voice took on the sound of a file rasping against iron. He laughed, a rather throaty laugh, like four dice shaken in a tin box. ‘Now, before we go out and get this man, nay, this fiend, are there any questions?’

‘Where do you think he is, Sir?’ asked Number Six.

‘Pardon?’ the Inspector said, putting his hand to his ear.

‘Where do you think Vernon is?’ Number Six asked again.

‘Yes, very good, very good, yes do that,’ the Inspector said, looking at Number Four.

‘Do what, Sir?’ Number Six asked yet again.

‘Well, that’s possible,’ the Inspector said, this time looking directly at policeman Number Three. ‘Are there any more questions? Come along now, you mustn’t be afraid of me just because I’m an officer.’ Out of the corner of his eye, he saw a hand raised by Number Seven. ‘Yes, what is the question?’ he grinned.

‘May I ask whether you heard the first question or not … Sir?’

The Inspector allowed his grin to widen before he spoke.

‘I would say between now and midnight,’ he said, taking out a large pocket watch and showing it to the men. ‘Good question that. I only hope all you other men are as quick and perceptive as that man there.’ He pointed to policeman Number Two. ‘Right, if that’s all you want to know, off you go, as I have work to do. I’m working on a plan.’

The rest of the policemen all looked at each other in an embarrassed way and filed out of the Inspector’s office. Only Sergeant Salt remained behind. When they were completely alone and the door had been closed the Sergeant spoke.

‘Excuse me … Sir … Sir … Inspector, Sir … Excuse me, Sir.’

The Inspector was busy looking at a street map and didn’t seem to hear, so the Sergeant tapped him on the right shoulder.

The Inspector jumped three feet into the air with fright. When he came down he looked at the Sergeant with a sickly grin and said in a voice as dry as autumn leaves, ‘What can I do for you, Corporal?’

‘Sergeant, Sir,’ the Sergeant beamed proudly.

‘Pardon?’

‘Sergeant, Sir. I’m a Sergeant, Sir.’

‘Good idea, no sugar in mine.’

The Sergeant slowly left the room and the Inspector was left alone in his office.

The Sergeant was the last man out of the station. All the other men had gone away in a group, a very close group, all believing in that old saying, ‘safety in numbers’.

From the police station steps, the Sergeant looked up the road, along the road and down the road. It was empty, not a soul in sight. He took a deep breath and walked down the station steps on to the street itself. Although a reasonably brave man, for the first time since he was a little boy, he felt scared of the dark. There was not a light to be seen. He walked as close to the railings as he could. He looked up at the closed curtains of the Inspector’s office.

‘He’ll be in there,’ the Sergeant thought, ‘wondering when his tea will be brought in.’

The Sergeant had gone about twenty nervous feet when he suddenly dropped to the ground. He had tripped over something. He was unhurt and jumped up as quickly as he could. In the darkness he groped with his hands on the ground hoping to find what had tripped him up. He soon found it. It wasn’t very nice. With many years’ experience behind him, he knew the second he touched it, that he had tripped over a body.

He looked round in the hope that there might be someone walking along who could give him a hand. But of course there was no-one. He even thought of shouting for the Inspector, but then thought better of it. If the Inspector couldn’t hear him when they were in the same room, what chance did he have of hearing him when he was out of the room?

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.