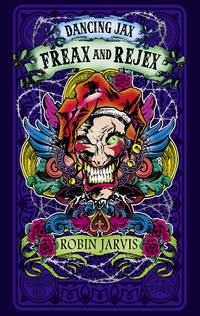

Полная версия

Freax and Rejex

“Shame I can’t apply it to Dancing Jax though, huh?”

“Oho,” he said. The old man inclined his head and touched his hat once more. “Sweet dreams,” he added.

Jody jerked her head aside. “Fat chance,” she huffed. “Been nothing but bad ones since this started.”

Jangler’s eyebrows lifted and the moustache jiggled on his lip. “How… distressing,” he murmured. “We must see what we can do about that, mustn’t we?”

Then he clicked his heels together, an action he immediately regretted because his feet were still suffering in those shoes, and continued on his way.

Something about the way he spoke those last words made Jody’s skin creep. Her eyes followed him till he reached the cabin at the other end. She wondered who, if anyone, was going to occupy the empty one next to it.

Jangler hesitated before entering. He turned his gaze towards the night-shrouded forest that surrounded the camp and chuckled to himself, knowing what was lurking out there. He gave another chuckle when he anticipated what would happen later, when everyone was asleep, and let himself in.

Lee circled the main block, testing each window he came across. Finally he found one that had been left open. He climbed inside and took a slim torch from the pocket of his trackie bottoms. He was in the lecture room, where the press conference had been held earlier that day, and where Sam, the cameraman, had later been lured by the Ismus, so the Black Face Dames could hold him down and force minchet into his mouth.

Lee shone the torchlight around; there was nothing in here, nothing he could use. As silently as possible, he made his way into the next room. It was the dining hall. The tables had been cleared, but the model of the castle still dominated the centre.

The boy curled his lip at it then made his way to the kitchen.

In there the torchlight bounced over the brushed steel surfaces and sparkled in the utensils hanging on the wall. Lee wasted no time. He pulled open every cupboard, searched in every drawer. Then he rushed to another door and yanked it open. Behind was a well-stocked storeroom, crammed from floor to ceiling with catering-sized tins and packets of dry goods. None of it was Mooncaster fare.

“Sweet!” he whispered as the torch beam revealed the treasures on the shelves.

He frowned when he realised he should have brought his holdall. He couldn’t carry more than two of those great tins at a time without it. Looking around, he saw, tucked under the lowest shelf, a collection of empty Tupperware containers.

“Hallelujah!” he muttered, smiling.

Taking the biggest, he put a bag of pasta and two bags of rice inside. Then he filled up the remaining space with packets of dried fruit and one of sugar. Sealing the lid back on and pocketing the torch, he carried the box through to the kitchen.

“I’ll be back for the rest of you foxy bitches,” he addressed the darkness of the storeroom.

It wasn’t long before he was climbing back out of the window. Kneeling on the ground outside, he waited till he was sure the coast was clear. Then, lugging the container, he darted over the lawn behind the main block – towards the forbidding expanse of night-smothered trees.

Lee wasn’t afraid of the deep gloom, but he almost choked at the rank smell that hit his nostrils as he pressed deeper into the wood. Was there a stagnant ditch close by? Hailing from an estate in South London, he wasn’t overly familiar with the countryside. Did it always stink like this? It was stronger than the drains in July.

Although he tried to move as silently as possible, the leaves of the previous autumn crunched as noisily as crisps and cornflakes under his trainers and twigs snapped even louder. When he had gone a short distance, he stopped and took out his torch again. He had to find something distinctive, something he would recognise again. Ahead he saw a fat tree. He had no idea what sort, but its bottommost branches spread out like two arms and the gnarled bark of the trunk suggested a face with puckered lips. It reminded him of a girl he had known in the days before the book. Yes, that would do.

He deposited the box at its base and hunted around for twigs and bracken to use as camouflage. As he collected it, the sensation he was being watched began to grow in his mind and the putrid smell of decay became stronger.

Unnerved, Lee looked around. It was too dark to see; the black shadows concealed everything and he hesitated to switch the torch on again.

“That you, pussy boy?” he murmured, thinking Marcus had followed him. “Don’t you try no tricks on me.”

There was no answer except the listless stirring of the leaves overhead and the faintest of noises, like the soft and subtle popping of bath foam. Lee turned towards the strange sound and thought he saw a shadow slide down from above. He blinked. Trying to pierce the darkness was a strain on the eyes.

He snapped on the torch. The beam shone directly on to the bubbling mass of black mould that was rearing in front of him.

ALASDAIR SAT HIMSELF down on the chalet step and picked out a tune on his guitar.

“Bit miserable,” a girl’s voice called over to him. “But you’re pretty good.”

He looked up and saw Jody still on her own step.

The Scot acknowledged her with a nod.

“You get in a lot of practice when there’s no anything else to do – and no pals to do it with neither,” he said. “And I like ‘miserable’.”

“So what bands you into?”

Alasdair shook his head. “Och, no,” he replied. “I’m no playing that game.”

“What game?”

“Do you really have to shout? Can you no come sit here and talk civil? I’ve got a hut full of wee lads trying to get their heads doon.”

Wrapping her green cardigan about her, the girl wandered over and sat next to him.

“What game?” she repeated.

“The ‘I know more obscure bands than you do’ game,” he said dismissively. “That sort of music snobbery doesnae interest me.”

Jody stood up again. “Oh, forget it,” she said, exasperated. “I was only trying to make conversation. I shouldn’t have bothered. None of you are worth bothering with. I keep telling myself I’m better off on my own; dunno why I don’t listen. Stick your ruddy guitar, stick your dirges and stick your snitty attitude.”

She turned to leave, but the boy asked her to wait.

“Sorry,” he groaned. “When you spend months being defensive, it’s a tough habit to crack and my social skills are rusty. Knee-jerk rude, that’s me. Sit down… please.”

“Not easy, is it?” she said, softening. “I’ve almost forgotten what it’s like to talk to someone normal.”

“Aye,” he agreed. “Would you look at the state of us – it’s tragic.”

“After what we’ve been through it’s not surprising: the riots, the firebombing of the bookshops, the persecution… And there’s only so many times you can get the hope and trust kicked out of you. We’re too scared to even try to make friends – I know I am and I can be a right cow about it.”

The boy laughed.

“I can!” she insisted. “I was foul to a little girl earlier. I wish – oh, it’s too late now.”

“We could learn a lot from the bairns here,” he told her. “They’re still able an’ willing to have a go at making pals without worrying it wilnae last. My lads in there are going to be thick as thieves come Monday morning.”

“The day they have to leave their new friends and go back to families who don’t want them,” Jody said bitterly. “Provided they haven’t been zombified by then.”

Alasdair looked down at his guitar and played the opening notes of a song.

“Well, that’s less miserable than the other one,” she observed.

“‘I am a Rock’ by Simon and Garfunkel,” he told her.

“And there’s you talking about obscure!”

“Good tunes are good tunes however old they are. It’s all ear food – and that one seemed appropriate.”

He gave the guitar his attention once more and sang the last few lines.

I touch no one and no one touches me.

I am a rock,

I am an island.

And a rock feels no pain;

And an island never cries.

“Do you have a pithy playlist for every occasion?” she asked dryly.

“Empathic jukebox, that’s me,” he answered with a grin. “Name’s Alasdair and – oh, no – I’m going to make friends with you so deal with it. If I’m not brainwashed by the end of this weekend, you can even have my mobile number. Make a change having someone call it. I dinnae bother charging it up half the time.”

Jody smiled with pleasure and the wall she had built around herself crumbled a little.

“Music’s always been a massive part of my life,” she said, gazing at the guitar. “When I was three, my mum and dad took me to Glastonbury. There’s photos of me covered in the thickest mud, like some midget swamp monster. We went back every other year. The bands I’ve seen…”

She looked off into the darkness of the distant trees. She didn’t want to think about the past. It was gone.

“Your mum and dad sound cool.”

“They were,” she said with a stark finality in her voice. “What about yours?”

Alasdair screeched his fingernail along a string for dramatic effect. “Next question!” he said evasively.

Jody tactfully reverted to the previous subject. “I wonder if they’ll even have Glastonbury this year?” she murmured. “I was going to go without them this time, just me and my best mate, before all this happened. If they do have it, it’ll probably be full of mass readings and minstrels and hey nonny nonnying.”

“Do they no have plenty of that there anyway, wi’ all the tree-hugging hippy caper and henna tattoos?”

Jody coughed to disguise her laughter. She’d hugged plenty of trees and had her hands decorated lots of times.

“That’s only a tiny part of it!” she said. “The best, most amazing artists in the world play on those stages. It’s incredible – was incredible.”

Before Alasdair could continue, they were distracted by Marcus emerging from the next cabin. He had changed into a Man United strip and came jogging over.

“Going to do some exercise before turning in,” he addressed the Scottish lad, ignoring Jody. “Want to join me?”

“No, I’m good thanks.”

“Play me something to work out to then!” Marcus called, trotting to the centre of the lawn, sparring with the night air as he hopped from foot to foot.

“I do believe I’d rather catch leprosy,” Alasdair remarked to Jody.

“He’s full of himself that one,” she said.

“Aye, well, that’s probably what’s kept him going. With me, it was my guitar. I dinnae know what I’d have done without it these past months. Takes my mind off it, mostly. How did you manage?”

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.