Полная версия

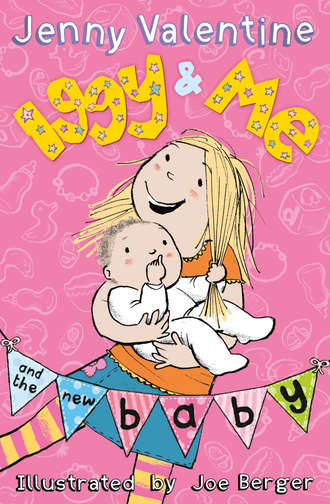

Iggy and Me and the New Baby

Title Page

1. Please May Can

2. Iggy’s New Teacher

3. Iggy’s Weekend News

4. The Measuring Door

5. The School Fair

6. Twenty Questions

7. In the Rabbit Hole

8. Iggy and Me and the New Baby

About the author

About the illustrator

Copyright

About the Publisher

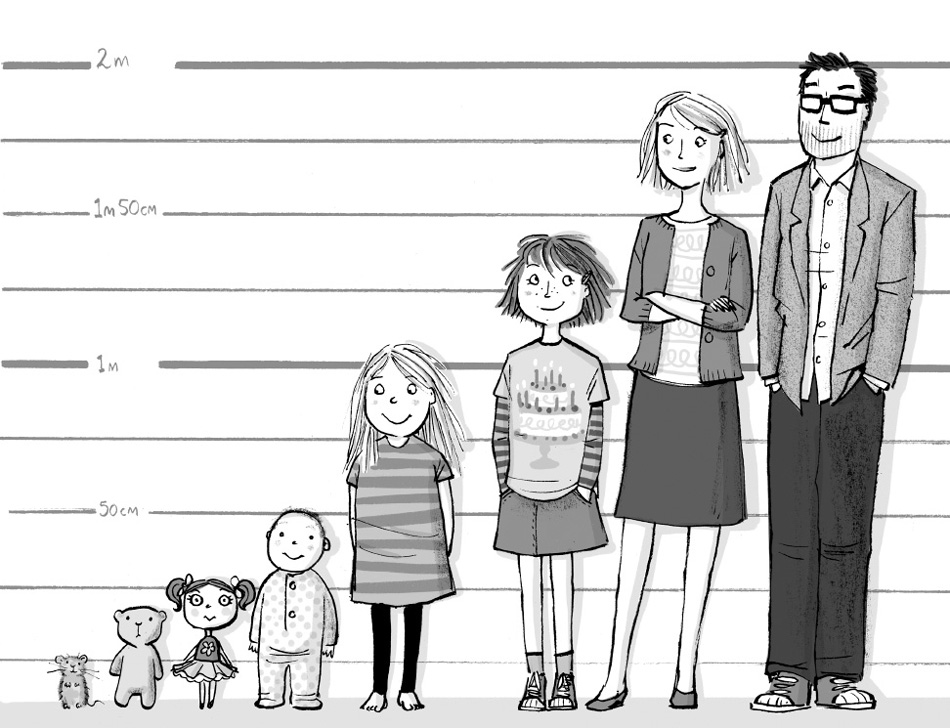

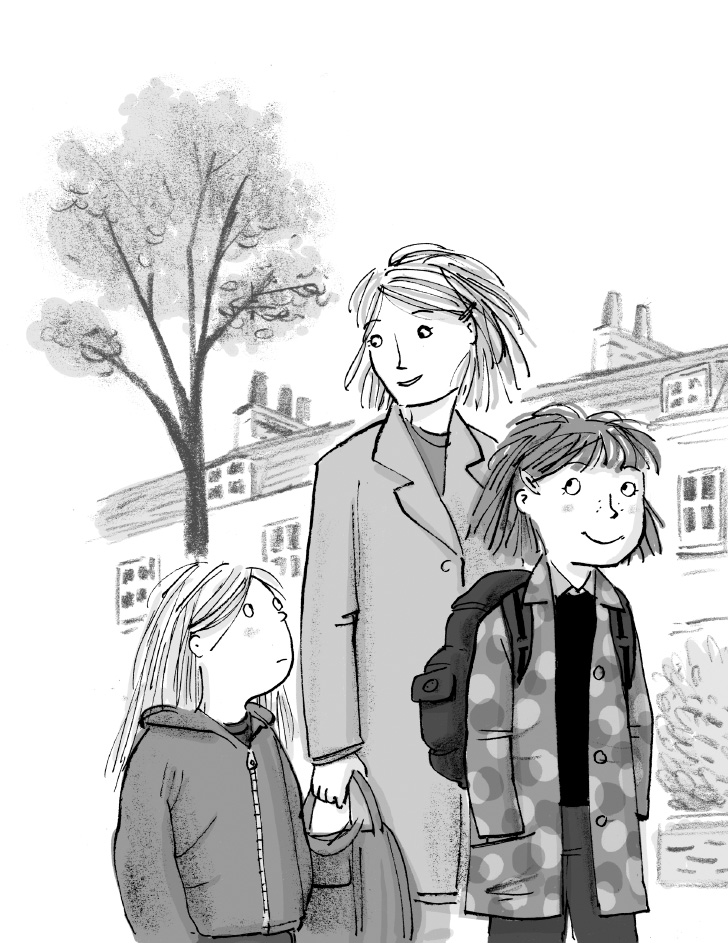

My name is Flo and I have a little sister called Iggy. I am nine and Iggy is six. We are each other’s only sister.

One morning, when we were walking to school, Iggy asked Mum a question.

She started with, “Please may can…”

I know that when Iggy uses all her polite words at once, she is really hoping for a ‘yes’. She says, “Please may can we have an ice cream and a biscuit?” and “Please may can we go on a bike ride and a picnic and sleep in a tent?”

“Please may can we have a baby?” Iggy asked, with her sweetest good-idea smile.

Mum slowed down, just a little bit.

“No, Iggy, I don’t think so.”

“How come?” said Iggy, and she looked a bit deflated, like an old balloon.

“Just because.”

Iggy said that wasn’t a reason.

“True,” said Mum. “You’ve got me there.”

“So why not?” Iggy asked, and then she added another, “Pleeease,” with extra ee’s, just to be on the safe side.

“I’ve had my babies,” Mum said, and she took our hands, mine and then Iggy’s. “You, and you.”

“You can have more than two children.” Iggy smiled, like that solved it.

“I know that.” Mum smiled back.

Iggy told her, “Thomas Wilkes’s mum has got eight.”

“Nine,” I said.

“Nine?” said Mum.

“Yes.” I counted on my fingers. “Thomas, Ruby, Emma, James, Sophie, Will, Patrick, Sarah and Ben.”

“Wow,” said Mum. “Nine.”

“James is in my class,” I said, “and Thomas is in Iggy’s. That’s how we know. When they go to the supermarket, they have to buy nine of everything.”

Iggy counted, “Nine toothbrushes, nine pairs of pants, nine packets of lemon drizzle cakes.”

Iggy loves lemon drizzle cake.

I said, “The Wilkes’s house is full of people and noise all the time, even when it’s just them.”

Mum frowned. “Well, Mr and Mrs Wilkes might have wanted nine children, but two is enough for me and your dad. That’s what we decided. One under each arm in an emergency.”

“What emergency?” I said.

Iggy was quiet for a minute. “You and Dad have got four arms. There’s room for two more.”

“Good maths,” Mum said, but she didn’t tell me what the emergency was.

“Will you and Dad change your minds?” Iggy said.

“No,” said Mum. “Absolutely not,” and she ruffled my hair and gave Iggy her school bag and kissed her goodbye on the nose.

Iggy doesn’t do ‘absolutely nots’. In Iggy’s ears, an ‘absolutely not’ is always a ‘maybe’.

When Mum says, “Absolutely not,” about a thing, Iggy goes and asks Dad. And when Dad says, “Absolutely not,” she double checks with Mum. Iggy thinks there’s always a chance she’ll get lucky. Sometimes she does.

So later, at suppertime, Iggy asked Dad the question too.

“Please may can you and Mum please have one or two more babies?”

Dad’s mouth fell open. It was a bit full of supper.

“Ewww!” Iggy said, looking away and shielding her eyes with her hands. “Manners!”

Dad finished his mouthful. “I thought you were going to ask me to pass the salt or the butter. I didn’t think you were going to ask for babies.”

“Can you?” Iggy said. “Have one or two?”

“No,” said Mum.

“We can,” Dad said, “but we might not want to.”

Iggy huffed with confusion. “What does that mean? Do you want to, or not?”

“Not,” said Dad.

“Definitely not,” said Mum.

“Please?” said Iggy.

“Absolutely not,” said Mum again.

“Let’s talk about something else,” said Dad. “How was your day, Flo? What did you learn at school?”

I started to tell Dad all about solids and liquids and gases, because that’s what we’ve been doing in Science. Iggy was scowling into her soup, which is a liquid.

“I want one,” she said.

“Well, you can have one of your own,” Mum said. “When you’re older.”

“Yowch!” said Iggy. “I’m not doing that. Not ever.”

Dad and Mum looked at each other and smiled.

“Maybe you’ll change your mind,” said Mum.

“No way,” said Iggy, and she squeezed her eyes tight shut and shook her head.

“Oh well,” said Dad, helping himself to more cauliflower. “No babies for you then. Never mind.”

“Where were we?” Mum said. “What were you saying, Flo?”

“It’s not fair,” said Iggy, interrupting again, before I could even get started.

Not fair is Iggy’s explanation for a lot of things.

When Mum says no to sweets, it’s not fair.

When Iggy has to go to bed half an hour before me, it’s not fair.

When we have rice and broccoli with our supper and Iggy wants chips and beans, it’s not fair.

When Iggy decides we should go swimming and to the zoo and out for pizza and we don’t because it’s only a Wednesday and not anybody’s birthday, it’s not fair.

“Here we go,” said Dad, and he rolled his eyes and winked at me.

“But I really want a little brother or sister,” she moaned. “And it really isn’t fair.”

Dad said, “Flo’s got a little sister, haven’t you?”

“Yep,” I said.

“How’s that working out for you?” said Dad.

“So far so good,” I said.

“See.” Iggy pointed at me. “Flo’s got one. It’s so not fair.”

Mum stood up and cleared our plates away.

“Life isn’t fair, Iggy,” she said.

Iggy sighed and slumped forward with her forehead on the table. Her voice came out all squished and mumbly.

“I’ve noticed,” she said.

In the playground at school, all Iggy could think about and talk about was babies.

She said, “Flo, what do babies smell like?” and “Why do some babies look like old men?” and “How many babies is it possible to have?”

“I don’t know,” I said.

“How many days does it take to grow a baby?” and “Do babies have teeth?” and “Do all babies like mashed banana?”

“Iggy,” I said, “I don’t know.”

“Well, who does?” Iggy looked around the playground. “I need to find out.”

“Why don’t you ask James Wilkes?” I said. “He’s got lots of baby brothers and sisters. He’s probably an expert.”

“Will you ask him?” Iggy said. “He’s your friend.”

“You’re the one who wants to know,” I said, “but I’ll come with you.”

So Iggy took me to find James Wilkes and quiz him about babies.

“What are they like?” Iggy said.

“Smelly,” said James Wilkes.

“What else?”

James Wilkes shrugged. “Noisy.”

“What else?”

“Hungry.”

James Wilkes wasn’t nearly as interested in babies as Iggy. James Wilkes wanted to play football. James Wilkes always wants to play football.

“What else?” Iggy said. “Please tell me. It’s very important.”

“Loud,” said James Wilkes. “Smelly and noisy and hungry and loud,” and then he ran after a ball that bounced just past his feet.

“James Wilkes isn’t an expert,” Iggy told me. “He doesn’t know anything. He doesn’t even care. How can he not care?”

“Maybe he does,” I said. “Maybe he’s just had enough of babies right now.”

Iggy shrugged her shoulders high with disbelief. “How is that even possible?”

At home, all Iggy could think about and talk about was babies.

“Pleeease have one more,” she begged. “Just one.”

“I’m too old,” said Mum.

“Are you?” I said.

“Actually, no,” Mum said. “Not exactly. I’m too tired.”

Dad nodded. “Babies are exhausting. They are a lot of work.”

“We’ll help you,” Iggy said.

“Not enough,” said Dad.

“Oh please,” Iggy said. “Just. One. Tiny. Baby,” and she put her hands a bit apart to show just how tiny it might be.

“Sorry.” Mum shook her head. “Just thinking about it is making me tired.”

Iggy put her arms out from her sides, like a teapot with two spouts. She said, “What’s so exhausting about a weeny little baby?”

“Babies keep you awake at night,” Mum said. “They are very demanding.”

“Babies get cross about nothing for hours at a time,” Dad said.

“They need constant care and attention.”

“They are always shouting and they are always pooing and they are always hungry.”

“You two sound like James Wilkes,” Iggy said.

“Who’s that?” Dad asked.

“An expert on babies,” I told him.

Iggy glared at all of us.

“Iggy we are not having another baby,” Mum and Dad told her, at the same time. “Absolutely not.”

The next week after school, we were having milk and biscuits, and Mum said, “I saw Mrs Wilkes on the high street today.”

Iggy had been jabbering away like normal, swinging her legs and talking at a hundred miles an hour about crayons and guinea pigs and skipping, but suddenly she went a bit quiet.

“Did you?” I said.

“Yes,” Mum said. “And we had a nice chat.”

Iggy slipped down lower in her chair and her legs stopped swinging.

“What about?” I asked Mum.

“Oh, this and that.”

I took a big gulp of milk. Iggy was holding her breath. I could hear her not breathing.

“We talked about babies,” Mum said.

“That’s nice,” I said.

“Mrs Wilkes wanted to know where my baby was.”

Iggy’s eyes were perfect round circles and her mouth was a silent straight line.

“What baby?” I asked Mum.

“That’s what I said.”

Iggy made a little groaning noise. It just squeezed out of her. Her cheeks went very pink and she stared very hard at her biscuit.

“Mrs Wilkes was talking about the baby I had last week,” Mum said, looking straight at Iggy. “A baby girl called Clover. She was very keen to meet her.”

It was ever so quiet at the table after that. It was too quiet for me to crunch my biscuit. I had to suck it.

“Iggy,” Mum said in the end. “Did you make up a baby?”

Iggy shook her head. She kept her lips tight shut.

Mum said, “Think very hard before you answer me, young lady.”

Iggy thought very hard. We could see her thinking.

“One lie is bad enough,” Mum told her. “Another one won’t make it any better.”

Iggy’s eyebrows went pink, like they always do when she is about to cry. Her chin started to tremble.

“No tears,” Mum said. “Tears won’t get you out of trouble either.”

“I didn’t mean to say it.” Iggy still wasn’t looking at Mum.

“But you did,” Mum told her.

“I couldn’t help it,” Iggy said.

“Yes you could,” Mum said.

“I just pretended,” said Iggy. “I just told James Wilkes.”

“When?” I asked.

“At playtime,” Iggy said.

“And James Wilkes told his mum,” Mum said. “And she told me.”

Iggy looked at the floor.

“No more pretend babies, Iggy,” Mum said.

“OK.”

“Just you and Flo and me and Dad.”

“OK,” Iggy said.

“Sorry?” Mum said.

“Sorry.” Iggy nodded.

And nobody said another word about it.

Except when Dad kissed us good night and turned out the lights, he said, “Good night, Flo. Sleep tight, Iggy.” And then I heard him whisper, “Good night, Clover.”

Iggy’s teacher was leaving at the end of term and Iggy was extremely upset about it. Rwaida had always been her teacher, since the very first day Iggy started school.

Iggy was really going to miss her.

“I love her,” she sobbed, after her last day in Rwaida’s class. “I love her and I know where everything is.”

“Why does she have to go?” Iggy said. “Why? Why?” and she scrunched her hands together into one little fist.

Mum said, “You know Rwaida isn’t leaving forever. She’s just taking some time off for a happy reason. She will most probably come back.”

“Well, when will she be back?”

“When she has adopted her baby,” said Mum.

“She told us that,” Iggy said, “but I don’t know what it means.”

“Sometimes there are more children than there are families and everybody has to share,” I said.

Iggy frowned at me for a minute. She asked Mum, “Is that right?”

“Sort of. Some children don’t have families and some families have room for more children.”

I said, “Adopting is looking after a baby that you didn’t make.”

“You don’t have to grow it in your tummy?” asked Iggy.

“No,” said Mum. “And it’s not only babies that can be adopted. Children of all ages need families to take care of them.”

“This family has got room for more children,” said Iggy, spreading her arms as wide as they would go and turning round in a circle. “Can we adopt some?”

Mum shook her head. “I doubt it.”

“It wouldn’t have to be a baby,” Iggy said. “Just somebody smaller than me.”

“Wanting to be bigger than someone is not a good reason to adopt,” said Mum.

“Well, what is?” asked Iggy.

“Not having children of your own,” Mum said. “Or wanting to help others.”

“I like helping others,” Iggy said, still turning. “I am very good at that.”

“Yes you are,” said Mum. “And so is Rwaida. She has waited a long time for this baby.”

“I know how she feels,” said Iggy.

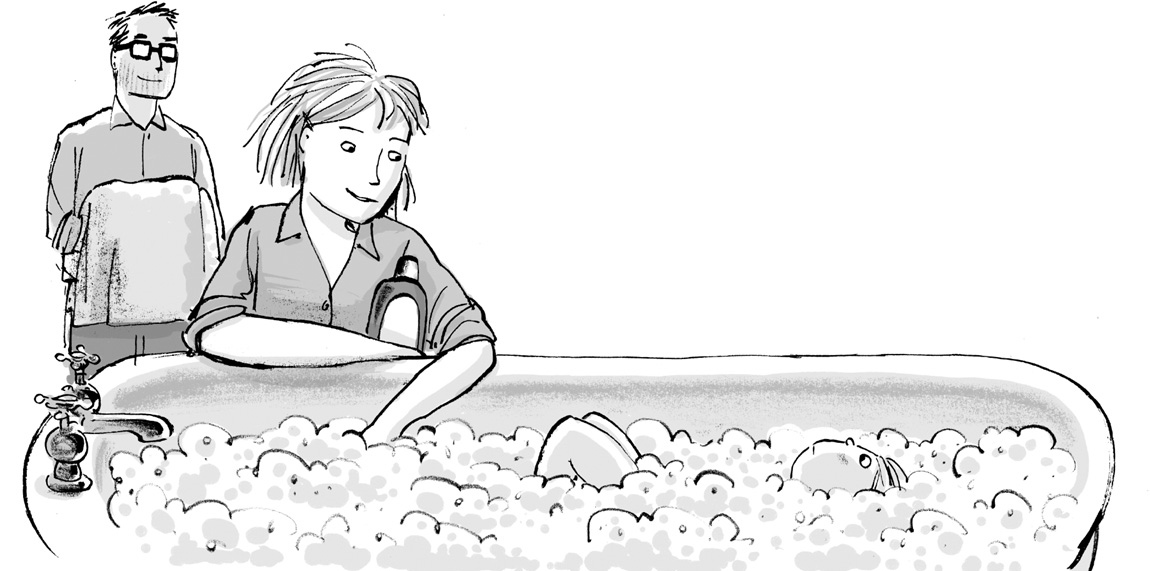

Later, at bathtime, Iggy said, “What will Rwaida do with her baby when she comes back to be my teacher?”

“What baby?” said Dad.

“The baby she is adopting,” Iggy told him, lying back in the bath with only her face showing through all the bubbles.

“Someone will look after her baby,” said Mum. “Someone in Rwaida’s family maybe, or a friend, or a childminder.”

Iggy sat up with a slosh and Mum poured some shampoo into her hands.

“Can I look after it?” Iggy said, screwing her eyes tight shut to keep out the shampoo.

“I’m very careful. I was very careful with Gruffles.”

“Gruffles was a hamster,” I said, with my mouth full of toothbrush.

“So?” Iggy said. “He was very precious and I didn’t break him.”

“Babies are a bit different to hamsters.” Dad rinsed the bubbles from Iggy’s hair. “And anyway, you’ll be at school.”

“True,” said Iggy. She climbed out of the bath and Dad wrapped her in a towel.

Iggy said, “Do you like helping others and taking care of other people’s children?”

“Why?” Dad said. “Is this a trick question?”

“Definitely,” said Mum.

Iggy shook her head. “Well, do you?”

Dad looked at me and Mum. “What did I miss?”

Iggy said, “We were thinking about adopting somebody smaller than me.”

“No we weren’t,” said Mum.

“We were talking about it,” Iggy said.

“You were talking about it,” Mum said. “We were talking about Rwaida adopting somebody smaller than you. That’s what we were talking about.”

Iggy looked up at Dad. “That’s why she won’t be my teacher any more.”

“Have you met your new teacher yet?” he asked.

Iggy looked glum. “Yes.”

I told them his name was Trevor. “But he likes to be called Mr Hawthorne.”

“Like a prickly old tree,” Iggy said.

“Oh dear,” said Dad. “Don’t you like Mr Hawthorne?”

Iggy gave Dad a withering look from inside her towel. “I can’t like him,” she said. “He’s not Rwaida and he’s got a moustache.”

“Grandad’s got a moustache,” Mum said.

“Not a big brown twirly one,” said Iggy. “Grandad’s moustache is smaller than Mr Hawthorne’s. And Grandad doesn’t wear cowboy boots.”

“Cowboy boots?” Mum and Dad smiled at each other.

“Yes,” Iggy said. “He’s got a twirly moustache and he plays the guitar and he wears cowboy boots. I love Rwaida. I’m never going to love Mr Hawthorne.”

“I’m not sure I’m loving him either,” said Dad.

“He is very different from Rwaida,” I said.

“Just wait and see,” said Mum.

Dad picked Iggy up in her towel and put her over his shoulder. “Bide your time. Wait for the right moment, and then show him who’s boss.”

“OK,” said Iggy.

“Not helpful,” said Mum.

On the way downstairs to the kitchen, Iggy’s chin began to wobble and her eyes filled up with tears. “I’m scared to have a teacher who isn’t Rwaida.”

Mum kissed her on the nose and said, “What are we going to do with you?”

“A biscuit would help,” Iggy sniffed.

A biscuit usually does.

At the kitchen table, Iggy blew on her hot milk. “What if Mr Hawthorne doesn’t know that it’s my turn to wipe the board on a Tuesday? What if he forgets I always collect the register on Fridays? How will he know where everybody sits? What if he tries to change stuff? What if he doesn’t like me? What if he only picks boys for all the good jobs because he is one?”

“Don’t worry, Iggy,” I said. “It’ll be OK.”

“How do you know?”

“Because Mr Hawthorne is actually just as nice as Rwaida, but in different ways.”

Iggy shook her head. “I’ve heard he is very strict and he doesn’t let you talk in the line and there is no calling out or going to the loo when you need to.”

“Well, then you will have to be quiet in the line and not call out or go to the loo all the time,” Dad told her.

“I know,” Iggy said. “That is exactly what I’ve been worrying about.”

“Mr Hawthorne was my teacher once or twice when my real teacher was away. He is actually a lot nicer than he looks,” I told her. “He’s very funny really and he’s got lots of good reading voices.”

“What does that mean?” Iggy said, through her biscuit.

“Well, when he’s being a giant, he sounds enormous and when he’s being a mouse, he sounds small and furry.”

“How does he do that?” Iggy said.

“I don’t know. He just does.”

Iggy raised her eyebrows and picked the crumbs off the table.

“What else does he do?” she asked.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.