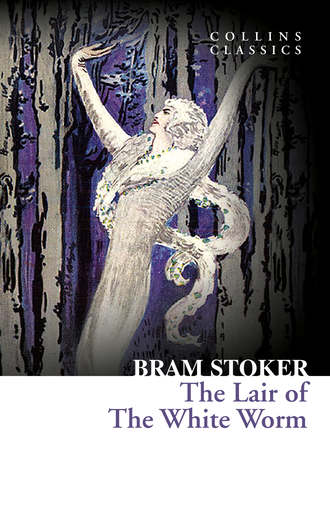

Полная версия

The Lair of the White Worm

Sir Nathaniel answered softly, laying his hand on the youth’s shoulder.

“You are right, my boy; quite right. That is the proper way to look at it. And I may tell you that we old men, who have no children of our own, feel our hearts growing warm when we hear words like those.”

Then Adam hurried on, speaking with a rush, as if he wanted to come to the crucial point.

“Mr. Watford had not come in, but Lilla and Mimi were at home, and they made me feel very welcome. They have all a great regard for my uncle. I am glad of that any way, for I like them all—much. We were having tea, when Mr. Caswall came to the door, attended by the negro. Lilla opened the door herself. The window of the living-room at the farm is a large one, and from within you cannot help seeing anyone coming. Mr. Caswall said he had ventured to call, as he wished to make the acquaintance of all his tenants, in a less formal way, and more individually, than had been possible to him on the previous day. The girls made him welcome—they are very sweet girls those, sir; someone will be very happy some day there—with either of them.”

“And that man may be you, Adam,” said Mr. Salton heartily.

A sad look came over the young man’s eyes, and the fire his uncle had seen there died out. Likewise the timbre left his voice, making it sound lonely.

“Such might crown my life. But that happiness, I fear, is not for me—or not without pain and loss and woe.”

“Well, it’s early days yet!” cried Sir Nathaniel heartily.

The young man turned on him his eyes, which had now grown excessively sad.

“Yesterday—a few hours ago—that remark would have given me new hope—new courage; but since then I have learned too much.”

The old man, skilled in the human heart, did not attempt to argue in such a matter.

“Too early to give in, my boy.”

“I am not of a giving-in kind,” replied the young man earnestly. “But, after all, it is wise to realise a truth. And when a man, though he is young, feels as I do—as I have felt ever since yesterday, when I first saw Mimi’s eyes—his heart jumps. He does not need to learn things. He knows.”

There was silence in the room, during which the twilight stole on imperceptibly. It was Adam who again broke the silence.

“Do you know, uncle, if we have any second sight in our family?”

“No, not that I ever heard about. Why?”

“Because,” he answered slowly, “I have a conviction which seems to answer all the conditions of second sight.”

“And then?” asked the old man, much perturbed.

“And then the usual inevitable. What in the Hebrides and other places, where the Sight is a cult—a belief—is called ‘the doom’—the court from which there is no appeal. I have often heard of second sight—we have many western Scots in Australia; but I have realised more of its true inwardness in an instant of this afternoon than I did in the whole of my life previously—a granite wall stretching up to the very heavens, so high and so dark that the eye of God Himself cannot see beyond. Well, if the Doom must come, it must. That is all.”

The voice of Sir Nathaniel broke in, smooth and sweet and grave.

“Can there not be a fight for it? There can for most things.”

“For most things, yes, but for the Doom, no. What a man can do I shall do. There will be—must be—a fight. When and where and how I know not, but a fight there will be. But, after all, what is a man in such a case?”

“Adam, there are three of us.” Salton looked at his old friend as he spoke, and that old friend’s eyes blazed.

“Ay, three of us,” he said, and his voice rang.

There was again a pause, and Sir Nathaniel endeavoured to get back to less emotional and more neutral ground.

“Tell us of the rest of the meeting. Remember we are all pledged to this. It is a fight à l’outrance, and we can afford to throw away or forgo no chance.”

“We shall throw away or lose nothing that we can help. We fight to win, and the stake is a life—perhaps more than one—we shall see.” Then he went on in a conversational tone, such as he had used when he spoke of the coming to the farm of Edgar Caswall: “When Mr. Caswall came in, the negro went a short distance away and there remained. It gave me the idea that he expected to be called, and intended to remain in sight, or within hail. Then Mimi got another cup and made fresh tea, and we all went on together.”

“Was there anything uncommon—were you all quite friendly?” asked Sir Nathaniel quietly.

“Quite friendly. There was nothing that I could notice out of the common—except,” he went on, with a slight hardening of the voice, “except that he kept his eyes fixed on Lilla, in a way which was quite intolerable to any man who might hold her dear.”

“Now, in what way did he look?” asked Sir Nathaniel.

“There was nothing in itself offensive; but no one could help noticing it.”

“You did. Miss Watford herself, who was the victim, and Mr. Caswall, who was the offender, are out of range as witnesses. Was there anyone else who noticed?”

“Mimi did. Her face flamed with anger as she saw the look.”

“What kind of look was it? Over-ardent or too admiring, or what? Was it the look of a lover, or one who fain would be? You understand?”

“Yes, sir, I quite understand. Anything of that sort I should of course notice. It would be part of my preparation for keeping my self-control—to which I am pledged.”

“If it were not amatory, was it threatening? Where was the offence?”

Adam smiled kindly at the old man.

“It was not amatory. Even if it was, such was to be expected. I should be the last man in the world to object, since I am myself an offender in that respect. Moreover, not only have I been taught to fight fair, but by nature I believe I am just. I would be as tolerant of and as liberal to a rival as I should expect him to be to me. No, the look I mean was nothing of that kind. And so long as it did not lack proper respect, I should not of my own part condescend to notice it. Did you ever study the eyes of a hound?”

“At rest?”

“No, when he is following his instincts! Or, better still,” Adam went on, “the eyes of a bird of prey when he is following his instincts. Not when he is swooping, but merely when he is watching his quarry?”

“No,” said Sir Nathaniel, “I don’t know that I ever did. Why, may I ask?”

“That was the look. Certainly not amatory or anything of that kind—yet it was, it struck me, more dangerous, if not so deadly as an actual threatening.”

Again there was a silence, which Sir Nathaniel broke as he stood up:

“I think it would be well if we all thought over this by ourselves. Then we can renew the subject.”

CHAPTER 7

Oolanga

Mr. Salton had an appointment for six o’clock at Liverpool. When he had driven off, Sir Nathaniel took Adam by the arm.

“May I come with you for a while to your study? I want to speak to you privately without your uncle knowing about it, or even what the subject is. You don’t mind, do you? It is not idle curiosity. No, no. It is on the subject to which we are all committed.”

“Is it necessary to keep my uncle in the dark about it? He might be offended.”

“It is not necessary; but it is advisable. It is for his sake that I asked. My friend is an old man, and it might concern him unduly—even alarm him. I promise you there shall be nothing that could cause him anxiety in our silence, or at which he could take umbrage.”

“Go on, sir!” said Adam simply.

“You see, your uncle is now an old man. I know it, for we were boys together. He has led an uneventful and somewhat self-contained life, so that any such condition of things as has now arisen is apt to perplex him from its very strangeness. In fact, any new matter is trying to old people. It has its own disturbances and its own anxieties, and neither of these things are good for lives that should be restful. Your uncle is a strong man, with a very happy and placid nature. Given health and ordinary conditions of life, there is no reason why he should not live to be a hundred. You and I, therefore, who both love him, though in different ways, should make it our business to protect him from all disturbing influences. I am sure you will agree with me that any labour to this end would be well spent. All right, my boy! I see your answer in your eyes; so we need say no more of that. And now,” here his voice changed, “tell me all that took place at that interview. There are strange things in front of us—how strange we cannot at present even guess. Doubtless some of the difficult things to understand which lie behind the veil will in time be shown to us to see and to understand. In the meantime, all we can do is to work patiently, fearlessly, and unselfishly, to an end that we think is right. You had got so far as where Lilla opened the door to Mr. Caswall and the negro. You also observed that Mimi was disturbed in her mind at the way Mr. Caswall looked at her cousin.”

“Certainly—though ‘disturbed’ is a poor way of expressing her objection.”

“Can you remember well enough to describe Caswall’s eyes, and how Lilla looked, and what Mimi said and did? Also Oolanga, Caswall’s West African servant.”

“I’ll do what I can, sir. All the time Mr. Caswall was staring, he kept his eyes fixed and motionless—but not as if he was in a trance. His forehead was wrinkled up, as it is when one is trying to see through or into something. At the best of times his face has not a gentle expression; but when it was screwed up like that it was almost diabolical. It frightened poor Lilla so that she trembled, and after a bit got so pale that I thought she had fainted. However, she held up and tried to stare back, but in a feeble kind of way. Then Mimi came close and held her hand. That braced her up, and—still, never ceasing her return stare—she got colour again and seemed more like herself.”

“Did he stare too?”

“More than ever. The weaker Lilla seemed, the stronger he became, just as if he were feeding on her strength. All at once she turned round, threw up her hands, and fell down in a faint. I could not see what else happened just then, for Mimi had thrown herself on her knees beside her and hid her from me. Then there was something like a black shadow between us, and there was the nigger, looking more like a malignant devil than ever. I am not usually a patient man, and the sight of that ugly devil is enough to make one’s blood boil. When he saw my face, he seemed to realise danger—immediate danger—and slunk out of the room as noiselessly as if he had been blown out. I learned one thing, however—he is an enemy, if ever a man had one.”

“That still leaves us three to two!” put in Sir Nathaniel.

“Then Caswall slunk out, much as the nigger had done. When he had gone, Lilla recovered at once.”

“Now,” said Sir Nathaniel, anxious to restore peace, “have you found out anything yet regarding the negro? I am anxious to be posted regarding him. I fear there will be, or may be, grave trouble with him.”

“Yes, sir, I’ve heard a good deal about him—of course it is not official; but hearsay must guide us at first. You know my man Davenport—private secretary, confidential man of business, and general factotum. He is devoted to me, and has my full confidence. I asked him to stay on board the West African and have a good look round, and find out what he could about Mr. Caswall. Naturally, he was struck with the aboriginal savage. He found one of the ship’s stewards, who had been on the regular voyages to South Africa. He knew Oolanga and had made a study of him. He is a man who gets on well with niggers, and they open their hearts to him. It seems that this Oolanga is quite a great person in the nigger world of the African West Coast. He has the two things which men of his own colour respect: he can make them afraid, and he is lavish with money. I don’t know whose money—but that does not matter. They are always ready to trumpet his greatness. Evil greatness it is—but neither does that matter. Briefly, this is his history. He was originally a witch-finder—about as low an occupation as exists amongst aboriginal savages. Then he got up in the world and became an Obi-man, which gives an opportunity to wealth via blackmail. Finally, he reached the highest honour in hellish service. He became a user of Voodoo, which seems to be a service of the utmost baseness and cruelty. I was told some of his deeds of cruelty, which are simply sickening. They made me long for an opportunity of helping to drive him back to hell. You might think to look at him that you could measure in some way the extent of his vileness; but it would be a vain hope. Monsters such as he is belong to an earlier and more rudimentary stage of barbarism. He is in his way a clever fellow—for a nigger; but is none the less dangerous or the less hateful for that. The men in the ship told me that he was a collector: some of them had seen his collections. Such collections! All that was potent for evil in bird or beast, or even in fish. Beaks that could break and rend and tear—all the birds represented were of a predatory kind. Even the fishes are those which are born to destroy, to wound, to torture. The collection, I assure you, was an object lesson in human malignity. This being has enough evil in his face to frighten even a strong man. It is little wonder that the sight of it put that poor girl into a dead faint!”

Nothing more could be done at the moment, so they separated.

Adam was up in the early morning and took a smart walk round the Brow. As he was passing Diana’s Grove, he looked in on the short avenue of trees, and noticed the snakes killed on the previous morning by the mongoose. They all lay in a row, straight and rigid, as if they had been placed by hands. Their skins seemed damp and sticky, and they were covered all over with ants and other insects. They looked loathsome, so after a glance, he passed on.

A little later, when his steps took him, naturally enough, past the entrance to Mercy Farm, he was passed by the negro, moving quickly under the trees wherever there was shadow. Laid across one extended arm, looking like dirty towels across a rail, he had the horrid-looking snakes. He did not seem to see Adam. No one was to be seen at Mercy except a few workmen in the farmyard, so, after waiting on the chance of seeing Mimi, Adam began to go slowly home.

Once more he was passed on the way. This time it was by Lady Arabella, walking hurriedly and so furiously angry that she did not recognise him, even to the extent of acknowledging his bow.

When Adam got back to Lesser Hill, he went to the coach-house where the box with the mongoose was kept, and took it with him, intending to finish at the Mound of Stone what he had begun the previous morning with regard to the extermination. He found that the snakes were even more easily attacked than on the previous day; no less than six were killed in the first half-hour. As no more appeared, he took it for granted that the morning’s work was over, and went towards home. The mongoose had by this time become accustomed to him, and was willing to let himself be handled freely. Adam lifted him up and put him on his shoulder and walked on. Presently he saw a lady advancing towards him, and recognised Lady Arabella.

Hitherto the mongoose had been quiet, like a playful affectionate kitten; but when the two got close, Adam was horrified to see the mongoose, in a state of the wildest fury, with every hair standing on end, jump from his shoulder and run towards Lady Arabella. It looked so furious and so intent on attack that he called a warning.

“Look out—look out! The animal is furious and means to attack.”

Lady Arabella looked more than ever disdainful and was passing on; the mongoose jumped at her in a furious attack. Adam rushed forward with his stick, the only weapon he had. But just as he got within striking distance, the lady drew out a revolver and shot the animal, breaking his backbone. Not satisfied with this, she poured shot after shot into him till the magazine was exhausted. There was no coolness or hauteur about her now; she seemed more furious even than the animal, her face transformed with hate, and as determined to kill as he had appeared to be. Adam, not knowing exactly what to do, lifted his hat in apology and hurried on to Lesser Hill.

CHAPTER 8

Survivals

At breakfast Sir Nathaniel noticed that Adam was put out about something, but he said nothing. The lesson of silence is better remembered in age than in youth. When they were both in the study, where Sir Nathaniel followed him, Adam at once began to tell his companion of what had happened. Sir Nathaniel looked graver and graver as the narration proceeded, and when Adam had stopped he remained silent for several minutes, before speaking.

“This is very grave. I have not formed any opinion yet; but it seems to me at first impression that this is worse than anything I had expected.”

“Why, sir?” said Adam. “Is the killing of a mongoose—no matter by whom—so serious a thing as all that?”

His companion smoked on quietly for quite another few minutes before he spoke.

“When I have properly thought it over I may moderate my opinion, but in the meantime it seems to me that there is something dreadful behind all this—something that may affect all our lives—that may mean the issue of life or death to any of us.”

Adam sat up quickly.

“Do tell me, sir, what is in your mind—if, of course, you have no objection, or do not think it better to withhold it.”

“I have no objection, Adam—in fact, if I had, I should have to overcome it. I fear there can be no more reserved thoughts between us.”

“Indeed, sir, that sounds serious, worse than serious!”

“Adam, I greatly fear that the time has come for us—for you and me, at all events—to speak out plainly to one another. Does not there seem something very mysterious about this?”

“I have thought so, sir, all along. The only difficulty one has is what one is to think and where to begin.”

“Let us begin with what you have told me. First take the conduct of the mongoose. He was quiet, even friendly and affectionate with you. He only attacked the snakes, which is, after all, his business in life.”

“That is so!”

“Then we must try to find some reason why he attacked Lady Arabella.”

“May it not be that a mongoose may have merely the instinct to attack, that nature does not allow or provide him with the fine reasoning powers to discriminate who he is to attack?”

“Of course that may be so. But, on the other hand, should we not satisfy ourselves why he does wish to attack anything? If for centuries, this particular animal is known to attack only one kind of other animal, are we not justified in assuming that when one of them attacks a hitherto unclassed animal, he recognises in that animal some quality which it has in common with the hereditary enemy?”

“That is a good argument, sir,” Adam went on, “but a dangerous one. If we followed it out, it would lead us to believe that Lady Arabella is a snake.”

“We must be sure, before going to such an end, that there is no point as yet unconsidered which would account for the unknown thing which puzzles us.”

“In what way?”

“Well, suppose the instinct works on some physical basis—for instance, smell. If there were anything in recent juxtaposition to the attacked which would carry the scent, surely that would supply the missing cause.”

“Of course!” Adam spoke with conviction.

“Now, from what you tell me, the negro had just come from the direction of Diana’s Grove, carrying the dead snakes which the mongoose had killed the previous morning. Might not the scent have been carried that way?”

“Of course it might, and probably was. I never thought of that. Is there any possible way of guessing approximately how long a scent will remain? You see, this is a natural scent, and may derive from a place where it has been effective for thousands of years. Then, does a scent of any kind carry with it any form or quality of another kind, either good or evil? I ask you because one ancient name of the house lived in by the lady who was attacked by the mongoose was ‘The Lair of the White Worm.’ If any of these things be so, our difficulties have multiplied indefinitely. They may even change in kind. We may get into moral entanglements; before we know it, we may be in the midst of a struggle between good and evil.”

Sir Nathaniel smiled gravely.

“With regard to the first question—so far as I know, there are no fixed periods for which a scent may be active—I think we may take it that that period does not run into thousands of years. As to whether any moral change accompanies a physical one, I can only say that I have met no proof of the fact. At the same time, we must remember that ‘good’ and ‘evil’ are terms so wide as to take in the whole scheme of creation, and all that is implied by them and by their mutual action and reaction. Generally, I would say that in the scheme of a First Cause anything is possible. So long as the inherent forces or tendencies of any one thing are veiled from us we must expect mystery.”

“There is one other question on which I should like to ask your opinion. Suppose that there are any permanent forces appertaining to the past, what we may call ‘survivals,’ do these belong to good as well as to evil? For instance, if the scent of the primaeval monster can so remain in proportion to the original strength, can the same be true of things of good import?”

Sir Nathaniel thought for a while before he answered.

“We must be careful not to confuse the physical and the moral. I can see that already you have switched on the moral entirely, so perhaps we had better follow it up first. On the side of the moral, we have certain justification for belief in the utterances of revealed religion. For instance, ‘the effectual fervent prayer of a righteous man availeth much’ is altogether for good. We have nothing of a similar kind on the side of evil. But if we accept this dictum we need have no more fear of ‘mysteries’: these become thenceforth merely obstacles.”

Adam suddenly changed to another phase of the subject.

“And now, sir, may I turn for a few minutes to purely practical things, or rather to matters of historical fact?”

Sir Nathaniel bowed acquiescence.

“We have already spoken of the history, so far as it is known, of some of the places round us—‘Castra Regis,’ ‘Diana’s Grove,’ and ‘The Lair of the White Worm.’ I would like to ask if there is anything not necessarily of evil import about any of the places?”

“Which?” asked Sir Nathaniel shrewdly.

“Well, for instance, this house and Mercy Farm?”

“Here we turn,” said Sir Nathaniel, “to the other side, the light side of things. Let us take Mercy Farm first. When Augustine was sent by Pope Gregory to Christianise England, in the time of the Romans, he was received and protected by Ethelbert, King of Kent, whose wife, daughter of Charibert, King of Paris, was a Christian, and did much for Augustine. She founded a nunnery in memory of Columba, which was named Sedes misericordiæ, the House of Mercy, and, as the region was Mercian, the two names became involved. As Columba is the Latin for dove, the dove became a sort of signification of the nunnery. She seized on the idea and made the newly-founded nunnery a house of doves. Someone sent her a freshly-discovered dove, a sort of carrier, but which had in the white feathers of its head and neck the form of a religious cowl. The nunnery flourished for more than a century, when, in the time of Penda, who was the reactionary of heathendom, it fell into decay. In the meantime the doves, protected by religious feeling, had increased mightily, and were known in all Catholic communities. When King Offa ruled in Mercia, about a hundred and fifty years later, he restored Christianity, and under its protection the nunnery of St. Columba was restored and its doves flourished again. In process of time this religious house again fell into desuetude; but before it disappeared it had achieved a great name for good works, and in especial for the piety of its members. If deeds and prayers and hopes and earnest thinking leave anywhere any moral effect, Mercy Farm and all around it have almost the right to be considered holy ground.”