Полная версия

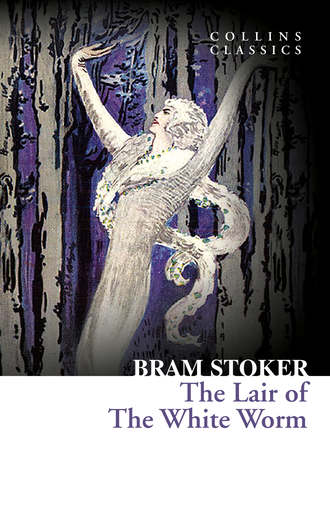

The Lair of the White Worm

THE LAIR OF THE WHITE WORM

Bram Stoker

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook published by William Collins in 2015

Life & Times section © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

Gerard Cheshire asserts his moral right as author of the Life & Times section

Classic Literature: Words and Phrases adapted from

Collins English Dictionary

Cover by e-Digital Design. Cover image: 1911 1st edition illustration by Pamela Colman Smith, courtesy Wikicommons

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008110505

Ebook Edition © January 2015 ISBN: 9780008110512

Version: 2014-12-18

History of Collins

In 1819, millworker William Collins from Glasgow, Scotland, set up a company for printing and publishing pamphlets, sermons, hymn books, and prayer books. That company was Collins and was to mark the birth of HarperCollins Publishers as we know it today. The long tradition of Collins dictionary publishing can be traced back to the first dictionary William published in 1824, Greek and English Lexicon. Indeed, from 1840 onwards, he began to produce illustrated dictionaries and even obtained a licence to print and publish the Bible.

Soon after, William published the first Collins novel, Ready Reckoner; however, it was the time of the Long Depression, where harvests were poor, prices were high, potato crops had failed, and violence was erupting in Europe. As a result, many factories across the country were forced to close down and William chose to retire in 1846, partly due to the hardships he was facing.

Aged 30, William’s son, William II, took over the business. A keen humanitarian with a warm heart and a generous spirit, William II was truly “Victorian” in his outlook. He introduced new, up-to-date steam presses and published affordable editions of Shakespeare’s works and The Pilgrim’s Progress, making them available to the masses for the first time. A new demand for educational books meant that success came with the publication of travel books, scientific books, encyclopedias, and dictionaries. This demand to be educated led to the later publication of atlases, and Collins also held the monopoly on scripture writing at the time.

In the 1860s Collins began to expand and diversify and the idea of “books for the millions” was developed. Affordable editions of classical literature were published, and in 1903 Collins introduced 10 titles in their Collins Handy Illustrated Pocket Novels. These proved so popular that a few years later this had increased to an output of 50 volumes, selling nearly half a million in their year of publication. In the same year, The Everyman’s Library was also instituted, with the idea of publishing an affordable library of the most important classical works, biographies, religious and philosophical treatments, plays, poems, travel, and adventure. This series eclipsed all competition at the time, and the introduction of paperback books in the 1950s helped to open that market and marked a high point in the industry.

HarperCollins is and has always been a champion of the classics, and the current Collins Classics series follows in this tradition – publishing classical literature that is affordable and available to all. Beautifully packaged, highly collectible, and intended to be reread and enjoyed at every opportunity.

Life & Times

The Lair of the White Worm

The Lair of the White Worm was published the year before Bram Stoker’s death, in 1911. Like Dracula the tale was loosely based on folklore, a fable from the north-east of England featuring a serpentine dragon named the Lambton Worm. There were many variations on the story; part of an oral tradition of storytelling, different narrators had adapted and embellished it over the centuries.

Stoker’s nightmarish monster lives in a lair and terrorizes the characters in the novel, and the plot is ultimately a classic tale of good versus evil. To reflect this theme the novel was also titled The Garden of Evil. Despite following the author’s success with Dracula, the novel was well-received and has since become something of a classic in the horror genre.

The original novel included a number of illustrations by Pamela Colman Smith, one of which is featured on the cover of this edition. She met Stoker in 1900 when both were involved with the Lyceum Theatre Group. He was the business manager and she the costume designer.

Dracula

When Stoker published his definitive story of Count Dracula the vampire, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein had already been in print for 69 years and had enjoyed great success. It told a similarly satanic story of a Victor Frankenstein who fabricated a corpse, brought it to life using electricity and suffered the consequences of interfering with nature. Clearly the Victorian public had a taste for literature that served to chill and thrill, so Dracula had an interested and ready readership.

In the story of Dracula, an English businessman, named Jonathan Harker, visits Count Dracula in his Eastern European castle to organize his estate. He soon finds himself trapped by Dracula and is subjected to all manner of frightening and supernatural horrors, however he manages to escape, only to be followed back to England. Dracula arrives in the form of a satanic beast, who has fed on the blood of sailors whilst crossing from the continent. The crewless ship is wrecked and rescuers find only the captain’s account of supernatural events onboard his ship. There is also a cargo of Transylvanian soil, which Dracula has brought with him as a home from home.

Soon Dracula is stalking Harker’s fiancée Wilhelmina and her friend Lucy. When Lucy begins to fall ill her blood is drained and she appears to die. However, by night she is resurrected as a vampire, where she begins victimizing children. Professor Abraham Van Helsing recognizes that Lucy has become a vampire, so she is ritually killed. Dracula reacts by infecting Wilhelmina and controlling her mind through telepathy. Ultimately Dracula is pursued back to his castle, as the Professor knows that the only way to save Wilhelmina is to put an end to Dracula.

Stoker’s book is made real by the way it is written. It comprises various accounts narrated by different characters and includes excerpts from newspaper reports. The result is a story that has the illusion of truth. This style of writing is known as epistolary and was also used by Mary Shelley in writing Frankenstein. From an author’s point of view the technique means that a story can be told in such a way that the central characters do not need to witness everything themselves and the inclusion of newspaper excerpts means that events can happen without any of the characters having been their as witnesses. Inevitably this approach mimics the way things happen in real life so that scenarios (fictitious events) take on the quality of actual events. Readers are left wondering whether they are reading the imaginings of an author or reportage, thereby blurring the boundary between fiction and non-fiction. Needless to say, this enables the reader to readily suspend their disbelief and become wholly absorbed by the story.

It would be difficult to think of another novel that has influenced a genre quite so much as Dracula, except perhaps Frankenstein. Together they form the foundation upon which most subsequent horror stories rest. In many respects the vampire and the monster have now become caricatures of themselves, but a read of the original books make’s one realize just how dark and Gothic those characters were upon first inception.

Vampire Legend

There have been so many permutations of the Dracula and vampire theme in modern culture in print, television and film that it is easy to forget how it all started, with the publication of Dracula the novel in 1897. In truth, Bram Stoker did not invent the idea of the vampire by any means, but his story brought together the various myths and legends that were already in existence into a cohesive whole. Stoker’s tale of Count Dracula caught the imagination of a Victorian audience and continues to appeal to readers to this day.

Stories of vampires had trickled through to England from Eastern Europe for centuries before Stoker was inspired to write. European folklore included tales of vampires from the late mediaeval period and these became embellished and retold as popular fireside stories. Perhaps the earliest example of a real person being accused of vampiric traits was a Croatian named Jure Grando. It was claimed that he rose from death to feast on the blood of the living and had to be decapitated when a stake through the heart proved ineffective.

At that time, in the late 17th century, people were entirely open to notions of witchcraft and supernatural powers as science and empiricism had yet to come to the fore. Word of mouth, secondhand accounts and circumstantial evidence were taken as proof in a world where they served as likely explanations for things that people found frightening and disturbing. People were religious too, so they were entirely indoctrinated with the notion of heaven and hell, and good and evil. We can never know the truth of the Grando case, but it certainly caught the public imagination.

By the 18th century things were beginning to get out of hand. Many people, both dead and alive, were accused of vampirism and found themselves staked or beheaded whenever unexplained misfortune fell upon others in the community. In cultures where illnesses and diseases were not understood scientifically it was only natural to presume that someone had cast a spell on them or done something unspeakable to them. So it was that perfectly innocent neighbours became scapegoats and were slain as vampires or else had their corpses disinterred only to die a second time.

By the 19th century the subject of vampires had entered the realm of considered debate. Many scholars denounced the whole idea, pointing out that all reports of vampires were nothing more than fictitious stories based on anecdote and hearsay. Furthermore, there wasn’t a scrap of scientific evidence that it was possible for people to become ‘the undead’ and transform into vampires under cover of darkness. Nevertheless, many people persisted in their beliefs – especially in the more remote regions of Eastern Europe.

Dedication

To my friend Bertha Nicoll with affectionate esteem.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

History of Collins

Life & Times

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Classic Literature: Words and Phrases

About the Publisher

CHAPTER 1

Adam Salton Arrives

Adam Salton sauntered into the Empire Club, Sydney, and found awaiting him a letter from his grand-uncle. He had first heard from the old gentleman less than a year before, when Richard Salton had claimed kinship, stating that he had been unable to write earlier, as he had found it very difficult to trace his grand-nephew’s address. Adam was delighted and replied cordially; he had often heard his father speak of the older branch of the family with whom his people had long lost touch. Some interesting correspondence had ensued. Adam eagerly opened the letter which had only just arrived, and conveyed a cordial invitation to stop with his grand-uncle at Lesser Hill, for as long a time as he could spare.

“Indeed,” Richard Salton went on, “I am in hopes that you will make your permanent home here. You see, my dear boy, you and I are all that remain of our race, and it is but fitting that you should succeed me when the time comes. In this year of grace, 1860, I am close on eighty years of age, and though we have been a long-lived race, the span of life cannot be prolonged beyond reasonable bounds. I am prepared to like you, and to make your home with me as happy as you could wish. So do come at once on receipt of this, and find the welcome I am waiting to give you. I send, in case such may make matters easy for you, a banker’s draft for £200. Come soon, so that we may both of us enjoy many happy days together. If you are able to give me the pleasure of seeing you, send me as soon as you can a letter telling me when to expect you. Then when you arrive at Plymouth or Southampton or whatever port you are bound for, wait on board, and I will meet you at the earliest hour possible.”

Old Mr. Salton was delighted when Adam’s reply arrived and sent a groom hot-foot to his crony, Sir Nathaniel de Salis, to inform him that his grand-nephew was due at Southampton on the twelfth of June.

Mr. Salton gave instructions to have ready a carriage early on the important day, to start for Stafford, where he would catch the 11.40 a.m. train. He would stay that night with his grand-nephew, either on the ship, which would be a new experience for him, or, if his guest should prefer it, at a hotel. In either case they would start in the early morning for home. He had given instructions to his bailiff to send the postillion carriage on to Southampton, to be ready for their journey home, and to arrange for relays of his own horses to be sent on at once. He intended that his grand-nephew, who had been all his life in Australia, should see something of rural England on the drive. He had plenty of young horses of his own breeding and breaking, and could depend on a journey memorable to the young man. The luggage would be sent on by rail to Stafford, where one of his carts would meet it. Mr. Salton, during the journey to Southampton, often wondered if his grand-nephew was as much excited as he was at the idea of meeting so near a relation for the first time; and it was with an effort that he controlled himself. The endless railway lines and switches round the Southampton Docks fired his anxiety afresh.

As the train drew up on the dockside, he was getting his hand traps together, when the carriage door was wrenched open and a young man jumped in.

“How are you, uncle? I recognised you from the photo you sent me! I wanted to meet you as soon as I could, but everything is so strange to me that I didn’t quite know what to do. However, here I am. I am glad to see you, sir. I have been dreaming of this happiness for thousands of miles; now I find that the reality beats all the dreaming!” As he spoke the old man and the young one were heartily wringing each other’s hands.

The meeting so auspiciously begun proceeded well. Adam, seeing that the old man was interested in the novelty of the ship, suggested that he should stay the night on board, and that he would himself be ready to start at any hour and go anywhere that the other suggested. This affectionate willingness to fall in with his own plans quite won the old man’s heart. He warmly accepted the invitation, and at once they became not only on terms of affectionate relationship, but almost like old friends. The heart of the old man, which had been empty for so long, found a new delight. The young man found, on landing in the old country, a welcome and a surrounding in full harmony with all his dreams throughout his wanderings and solitude, and the promise of a fresh and adventurous life. It was not long before the old man accepted him to full relationship by calling him by his Christian name. After a long talk on affairs of interest, they retired to the cabin, which the elder was to share. Richard Salton put his hands affectionately on the boy’s shoulders—though Adam was in his twenty-seventh year, he was a boy, and always would be, to his grand-uncle.

“I am so glad to find you as you are, my dear boy—just such a young man as I had always hoped for as a son, in the days when I still had such hopes. However, that is all past. But thank God there is a new life to begin for both of us. To you must be the larger part—but there is still time for some of it to be shared in common. I have waited till we should have seen each other to enter upon the subject; for I thought it better not to tie up your young life to my old one till we should have sufficient personal knowledge to justify such a venture. Now I can, so far as I am concerned, enter into it freely, since from the moment my eyes rested on you I saw my son—as he shall be, God willing—if he chooses such a course himself.”

“Indeed I do, sir—with all my heart!”

“Thank you, Adam, for that.” The old man’s eyes filled and his voice trembled. Then, after a long silence between them, he went on: “When I heard you were coming I made my will. It was well that your interests should be protected from that moment on. Here is the deed—keep it, Adam. All I have shall belong to you; and if love and good wishes, or the memory of them, can make life sweeter, yours shall be a happy one. Now, my dear boy, let us turn in. We start early in the morning and have a long drive before us. I hope you don’t mind driving? I was going to have the old travelling carriage in which my grandfather, your great-grand-uncle, went to Court when William IV. was king. It is all right—they built well in those days—and it has been kept in perfect order. But I think I have done better: I have sent the carriage in which I travel myself. The horses are of my own breeding, and relays of them shall take us all the way. I hope you like horses? They have long been one of my greatest interests in life.”

“I love them, sir, and I am happy to say I have many of my own. My father gave me a horse farm for myself when I was eighteen. I devoted myself to it, and it has gone on. Before I came away, my steward gave me a memorandum that we have in my own place more than a thousand, nearly all good.”

“I am glad, my boy. Another link between us.”

“Just fancy what a delight it will be, sir, to see so much of England—and with you!”

“Thank you again, my boy. I will tell you all about your future home and its surroundings as we go. We shall travel in old-fashioned state, I tell you. My grandfather always drove four-in-hand; and so shall we.”

“Oh, thanks, sir, thanks. May I take the ribbons sometimes?”

“Whenever you choose, Adam. The team is your own. Every horse we use to-day is to be your own.”

“You are too generous, uncle!”

“Not at all. Only an old man’s selfish pleasure. It is not every day that an heir to the old home comes back. And—oh, by the way … No, we had better turn in now—I shall tell you the rest in the morning.”

CHAPTER 2

The Caswalls of Castra Regis

Mr. Salton had all his life been an early riser, and necessarily an early waker. But early as he woke on the next morning—and although there was an excuse for not prolonging sleep in the constant whirr and rattle of the “donkey” engine winches of the great ship—he met the eyes of Adam fixed on him from his berth. His grand-nephew had given him the sofa, occupying the lower berth himself. The old man, despite his great strength and normal activity, was somewhat tired by his long journey of the day before, and the prolonged and exciting interview which followed it. So he was glad to lie still and rest his body, whilst his mind was actively exercised in taking in all he could of his strange surroundings. Adam, too, after the pastoral habit to which he had been bred, woke with the dawn, and was ready to enter on the experiences of the new day whenever it might suit his elder companion. It was little wonder, then, that, so soon as each realised the other’s readiness, they simultaneously jumped up and began to dress. The steward had by previous instructions early breakfast prepared, and it was not long before they went down the gangway on shore in search of the carriage.

They found Mr. Salton’s bailiff looking out for them on the dock, and he brought them at once to where the carriage was waiting in the street. Richard Salton pointed out with pride to his young companion the suitability of the vehicle for every need of travel. To it were harnessed four useful horses, with a postillion to each pair.

“See,” said the old man proudly, “how it has all the luxuries of useful travel—silence and isolation as well as speed. There is nothing to obstruct the view of those travelling and no one to overhear what they may say. I have used that trap for a quarter of a century, and I never saw one more suitable for travel. You shall test it shortly. We are going to drive through the heart of England; and as we go I’ll tell you what I was speaking of last night. Our route is to be by Salisbury, Bath, Bristol, Cheltenham, Worcester, Stafford; and so home.”

Adam remained silent a few minutes, during which he seemed all eyes, for he perpetually ranged the whole circle of the horizon.

“Has our journey to-day, sir,” he asked, “any special relation to what you said last night that you wanted to tell me?”

“Not directly; but indirectly, everything.”

“Won’t you tell me now—I see we cannot be overheard—and if anything strikes you as we go along, just run it in. I shall understand.”

So old Salton spoke:

“To begin at the beginning, Adam. That lecture of yours on ‘The Romans in Britain,’ a report of which you posted to me, set me thinking—in addition to telling me your tastes. I wrote to you at once and asked you to come home, for it struck me that if you were fond of historical research—as seemed a fact—this was exactly the place for you, in addition to its being the home of your own forebears. If you could learn so much of the British Romans so far away in New South Wales, where there cannot be even a tradition of them, what might you not make of the same amount of study on the very spot. Where we are going is in the real heart of the old kingdom of Mercia, where there are traces of all the various nationalities which made up the conglomerate which became Britain.”