Полная версия

Collins New Naturalist Library

Unlike the marsh harrier, the hen harrier has proved remarkably adaptable in its habitat requirements: indeed in the Americas it is the only harrier and occupies the combined niche of all the Old World species. In the north of Britain it has increased, despite fairly heavy persecution, and is doing particularly well in the new conifer plantations of Scotland, which are rich in ground rodents. On the whole, the hen harrier seems to be making good the ground it lost in the nineteenth century, when an even more intensive slaughter banished it from the Scottish mainland as a breeding species. In eastern Europe, the pallid harrier has expanded and increased its range from the Russian Steppes, in close association with the spread of agriculture. Thus human disturbance alone does not necessarily disturb birds of prey. This is shown by the distribution and breeding of the osprey on the eastern end of Long Island Sound in coastal Connecticut and New York with little regard for human activity; it nests on artificial man-made platforms as does the stork in Europe.

The difficulties of measuring the contribution of habitat change and the persecution of gamekeepers, skin and egg-collectors to the decline of the raptors is well illustrated in the case of the buzzard. The changing status of this bird has been very carefully documented by Dr N. W. Moore following a survey sponsored through the British Trust for Ornithology. Until the early nineteenth century the buzzard was to be found over virtually the whole of the British Isles. Then a serious decline occurred in East Anglia, the Midlands and much of Ireland in the mid-nineteenth century, followed by some recovery in the twentieth century. Today densities of 1–2 pairs per square mile can be expected in suitable habitats. The decline cannot be attributed directly to the spread of agriculture during the nineteenth century because the species underwent increases and decreases both during times of agricultural advance and recession. Also during this period the rabbit, one of the main foods of the buzzard, became more common. Similarly, more urbanisation took place between 1915 and 1954 when the buzzard was increasing, than during the years 1800–1915 when it was decreasing. Furthermore, in the 1954 survey, which indicated a British population of 20–30,000 birds, the highest buzzard density was recorded on mixed agricultural moorland, rather than in pure forest or on extensive moorland, where nesting sites seem to be in short supply. In fact, Moore attributes the early decline of the buzzard to the game-preservation which boomed from 1800–1914. Convincing evidence is provided by his maps, which show an inverse correlation between areas of intensive game-preservation, judged by the number of gamekeepers per square mile, and the distribution of buzzards. His view is also supported by the fact that the biggest recovery took place during the two world wars, when there was much less game-preservation, and many keepers were fighting a different adversary. However, the early decline of the buzzard in the nineteenth century is also temporally related to a marked decline of sheep farming, particularly in East Anglia, and, as discussed below in the case of the raven and carrion crow, the associated loss of carrion may have provided the initial cause, being only accelerated by keepers. Nor does persecution account for the disappearance of the buzzard from Ireland.

Myxomatosis was confirmed at Edenbridge in October 1953, and from two original outbreaks it rapidly spread until by early 1955 rabbits throughout the mainland of Britain were infected with a 99% lethal strain of the virus (Armour and Thompson 1955). The 1954 buzzard survey was carried out before there had been widespread reductions in rabbit numbers, but already many poultry farmers and shooting men were afraid that the bird would now turn to other forms of prey, particularly chickens and game-birds. The same concern was accorded the fox, but fortunately an investigation of this animal’s feeding habits had been made before myxomatosis by Southern and Watson (1941) and this was repeated by Lever (1959) on behalf of the Ministry of Agriculture in 1955. The results showed that in the absence of rabbits, foxes concentrated on other small rodents which would normally have been their second most important prey; the incidence of poultry or game-birds in stomach remains did not increase. This turned out to be roughly what happened in the case of the buzzards. Deprived of rabbits, they turned to other small rodents, but took no more game-birds or poultry than before. In the normal course of events the buzzard is not a very specialised feeder and takes a wide range of prey, including rabbits, small rodents, birds and invertebrates, so that their response to a density change in one prey species was as discussed above (see here). Although the buzzard could turn to other prey, it proved much more difficult for the birds to obtain enough food. The immediate consequence of myxomatosis was that many pairs failed to breed, while those that did attempt to nest laid fewer eggs and were much less successful than usual at rearing the young.

The deforestation in north-west Scotland which caused the loss of the roe deer, great-spotted woodpecker and other species (see here), also opened up the Western Highlands for sheep grazing (around 1800); at first good on the rich woodland soil, but subsequently poor as a result of soil degeneration and moor burning. Muirburn resulted in the loss of woody, nourishing and palatable plants leaving only those species resistant to fire. Associated with this spoliation of the habitat, the numbers of all local animals decreased, including grouse, mountain hares, woodcock, snipe and red deer. These last die in large numbers in winter because the impoverished habitat provides much too poor a food supply at the critical time – ideally, good management should ensure a better balance between summer and winter resources. For roughly the same reasons, many sheep die each winter and few lambs survive. A good deal of carrion therefore exists in the form of deer, lambs and ewes already doomed to die and this provides food for golden eagles in the area. Dr J. D. Lockie, who has examined the problem in detail in Wester Ross, has taken great care to discover to what extent eagles prey upon live sheep. Lambs taken as carrion have often lost their eyes as a result of crow attack, or have had limbs or ears bitten off by foxes. In catching live lambs the eagle’s talons cause considerable haemorrhage and bruising of the back, which can be recognised at a post-mortem. It is, therefore, fairly easy to distinguish the two sorts of prey by examining lamb carcases in eyries, and for 22 remains found at one eyrie between 1956 and 1961, 10 could be so categorised. Three of these lambs had been killed by eagles and seven taken as carrion. What could not be determined was how many of the live captures were weakling animals or twins – an important consideration in the case of attacks by ravens and carrion crows (see below). Nevertheless, the anti-eagle policy adopted by so many shepherds is understandable. Lockie was able to show that the percentage of lamb in the eagle’s diet averaged about 46% in years when lamb survival was average or poor, that is, when conditions for lamb rearing were poor; but it fell to 23% in years of high lamb survival. Hence, when lamb was not abundant the eagles compensated by turning to other prey. Clearly, sensible sheep management is the answer to any eagle problems, and it is not fair to attribute poor lamb seasons directly to eagle predation.

On the Isle of Lewis, complaints that eagles had been attacking sheep in 1954 were investigated by Lockie and Stephen on behalf of the Nature Conservancy. Here the main prey comprises rabbits, lamb and sheep carrion, supplemented by a few hares, grouse, rats, golden plover and hooded crows. Occasionally the eagles do attack live lambs and a pair which were seen to attack 5 lambs sparked off the complaints. Actually, out of thirteen local farmers and crofters interviewed, only two had seen eagles in the act of killing lambs, though two others believed that eagles did attack lambs. The eagle has increased on Lewis since about 1946, coincident with a decline in mountain hares, grouse and rabbits, but an increase in sheep. As the eagle density is now, if anything, higher on Lewis than in other areas of Scotland, where a much richer wild fauna exists, it seems that the high density is maintained by the sheep carrion, of which there is an excessive amount because sheep mortality is high. Overgrazing occurs and deficiency diseases are frequent. In one two-mile walk on 20 April, 28 carcases were counted. Again the basic problem is one of land management, the inefficient farmer being the one who suffers most.

The Western Highlands are mostly deer-forest where, with the exception of some shepherds, the hand of man is not specially directed against birds of prey. The attitude is that if these eat grouse they do good because an accidentally flushed grouse frightens deer and hinders the stalker. The attitude varies again in north-eastern Scotland. In parts of the southern Cairngorms, where Watson found about 12 eagle pairs in 220 square miles of suitable country, sheep are rare on the hills in winter and their density in summer is also low compared with Wester Ross and Lewis. Here eagles are rarely disturbed. Their food in summer comprises about 60% red grouse and ptarmigan and around 30% mountain hares and rabbits. On lower ground, which is grouse moorland, and also on the grouse moors of the southern Grampians, any bird with a hooked bill is considered a potential competitor with man for the grouse stocks – a totally unjustified view as we have seen. The effects of persecution are well-illustrated by a study made by Sandeman of breeding success among eagles in the south Grampians. Successful birds reared on average 1.4 young per year, but making allowance for non-breeders, or birds whose eggs or young were destroyed, gives a figure of 0.4 young per pair per year for the whole area. In the northern part of the area studied by Sandeman the land is primarily deer-forest and sheep ground, where eagles are little disturbed. Here the average success was 0.6 young per pair, which compares with a production of only 0.3 young per pair on nearby areas predominantly given over to grouse-management and sheep-grazing, and where persecution is considerable. The consequences of killing adult eagles are also reflected in the number of immature birds mated to old birds. In 24 territories on deer ground which were occupied over the years 1950–56, no member of any pair was ever immature and no bird was without a partner. In contrast, on the grouse and sheep moors where 51 occupied territories were watched over the same period, immature birds were paired to adults in four territories, while in eight territories only one member of the pair was present. Males or females mated to immature birds either did not breed, or if eggs were laid these were often infertile; killing could thus result in a suppression of breeding success in following years among the survivors. Immature birds were replacing lost adults and, although this replacement may have been insufficient as to saturate the pre-breeding population, it is possible that post-breeding numbers were little below par due to immigration. It is perhaps surprising that intensive killing had so little effect on this slow breeding species, but the area in question probably relied on immigration from areas with a higher breeding success, and were it not for the existence of such reservoirs killing would certainly have depressed total numbers. In the southern Cairngorms, Watson found that the average number of young leaving a successful nest was similar to the above at 1.3 young per pair. However, more pairs were successful and five which were closely studied by Watson reared 0.8 young per year. It is presumably from areas such as these that excess birds are produced which can replace the losses inflicted by man on the grouse estates.

The population of eagles in the deer-forest country of the remote North-West Highlands has probably long been near the maximum carrying capacity of the habitat, in spite of constant harrying by man in supposed defence of his sheep. It required the more subtle action of toxic insecticides to upset this balance, it being suggested that these derived from sheep dips containing organo-chlorine insecticides, particularly dieldrin. These chemicals contaminated carcases and were then accumulated by feeding eagles, with the result that their breeding efficiency was seriously impaired. Lockie and Ratcliffe (1964) found that the proportion of non-breeding eagles in western Scotland increased from 3% in 1937–60 to 41% in 1961–3, and the proportion of pairs rearing young fell from 72% to 29% in the same periods.

There is much stronger evidence that the peregrine has suffered drastically since toxic chemicals were introduced. In 1961 and 1962 Ratcliffe undertook a survey of the species for the B.T.O., primarily because pigeon fanciers had claimed that the species was increasing and threatening their interests. As it happened quite the opposite was found. The average British breeding population from 1930–9 had been about 650 pairs with territories, but in 1962 only about half these territories proved to be occupied, and successful nesting occurred in only 13% of 488 examined. There had been some depletion in the south of England during the war years of 1939–45, because the bird was outlawed as a potential predator of carrier pigeons with war dispatches, and was rigorously shot by the Air Ministry; it was almost exterminated on the south coast. Subsequently there was a rapid build-up in numbers in southern England, which were nearly back to the pre-war level by the mid-1950s. Then the second much more drastic and this time national decline took place, associated with a fall in nesting success and the frequent breaking and disappearance of eggs which the birds appeared to be eating themselves (see here). While the evidence that toxic chemicals were responsible was necessarily circumstantial, it was such that no reasonable person could wait for cut and dried scientific proof while there was a grave risk of losing much of our wild life in the meantime, and a voluntary ban on the use of these chemicals was agreed. All the same, the recovery of dead peregrines and their infertile eggs containing high residues of organo-chlorine insecticides, together with the coinciding of the decline with the increased usage of the more toxic insecticides, seems to indicate that pollution from these chemicals does account for the loss of these birds. In fact, fifteen infertile eggs from thirteen different eyries in 1963 and 1964 all contained either D.D.T., B.H.C., dieldrin, heptachlor or their metabolites. The distribution and residue level of these insecticides in adults and eggs shows that birds at the top of the food chain are highly susceptible to contamination. A sample of 137 of those territories examined in 1962 was again checked in 1963 and 1964. In 1962, 83 of these were occupied and in 42% of these young were produced (this is the best measure of nesting success), in 1963 only 62 of these territories were occupied but 44% produced young while 66 were occupied in 1964 and 53% produced young. There thus seems some hope that the alarming decline in numbers has been halted and that breeding success is returning to a more normal level. To complicate the picture, though certainly unconnected with the effect of toxic chemicals, there is some evidence that there has been a gradual fall in the peregrine population of the Western Highlands and Hebrides since the start of the century. Whether or not this decline followed the depletion of vertebrate prey in the region already referred to, is not at all clear.

Peregrines capture live prey, usually in flight, and, as Table 3 shows, domestic pigeons form a large proportion of the food in the breeding season. The peregrine is called duck hawk in the United States, and it can sometimes be seen on the estuary in winter instilling panic into wigeon and teal flocks, although duck form a relatively unimportant prey in the summer. It is surprising that the wood-pigeon is not taken more frequently, but it is likely that the adults, which average 500 gms, are too big; domestic and racing forms of the rock dove weigh 350–440 gms. In fact, the only wood-pigeons I have seen killed by the peregrine, and this was in S. E. Kent, were juveniles about 2–3 months out of the nest. In this area of Kent, peregrines seemed to do much better in autumn by concentrating on the flocks of migrants, particularly starlings, which pour into the country over the cliffs at Dover. It is not known to what extent peregrines take domestic or racing pigeons which have become lost and have joined wild populations and as a result are of no value to their owners. Ignoring this factor, but making various allowances for breeding and non-breeding birds, Ratcliffe estimated that the pre-war peregrine population (650 pairs) would consume about 68,000 pigeons per annum, while the depleted population in 1962 would eat about 16,500. This latter figure represents about 0.3% per annum of the total racing pigeon population of Britain, numbering about five million birds. To put this in proportion, there are about 5–10 million wood-pigeons in Britain, depending on the season, which are widely regarded as a pest of mankind – yet mankind happily finds food for 5,000,000 domesticated pigeons. In Belgium, the home of racing pigeons (one-third of the world’s pigeon fanciers are Belgian and one-fifth are British), the Federation of Pigeon Fanciers was offering a reward of 40 francs for evidence of the killing of red kite, sparrowhawk, peregrine or goshawk, in spite of the fact that Belgium has ratified the International Convention for the Protection of Birds under which such subsidies are forbidden. While education is again the answer to this kind of attitude it is slow to take effect. A big problem arises because pigeon racing, like greyhound racing, provides a relaxation which can be coupled with betting. As some pigeons are fairly valuable, and the loss of a race through a bird failing to home results in lost prizes or betting money, it is all too easy to lay the blame on a bird of prey.

There is much evidence that predators select ailing prey, and when this additional allowance is made it seems ludicrous to claim that peregrines can really do significant harm to racing pigeon interests. Rudebeck observed 260 hunts by peregrines. Of these only 19 were successful and in three of the cases the victim was suffering from an obvious abnormality. For 52 successful hunts by four species of predatory bird (sparrowhawk, goshawk, peregrine and sea eagle) he recorded that obviously abnormal individuals were selected in 19% of the cases – a much higher ratio of abnormal birds than would normally be expected in the wild. Thus when Hickey (1943) examined 10,000 starlings collected at random he reckoned that only 5% showed recognisable defects. M. H. Woodward, one time secretary of the British Falconers’ Club, quotes the case of 100 crows killed in Germany by trained falcons belonging to Herr Eutermoser. Sixty of these crows were judged to be fit, but the remainder were suffering from some sort of handicap, such as shot wounds, feather damage or poor body condition. But of 100 crows shot in the same district over the same period, only 23 were judged abnormal on the same criteria.

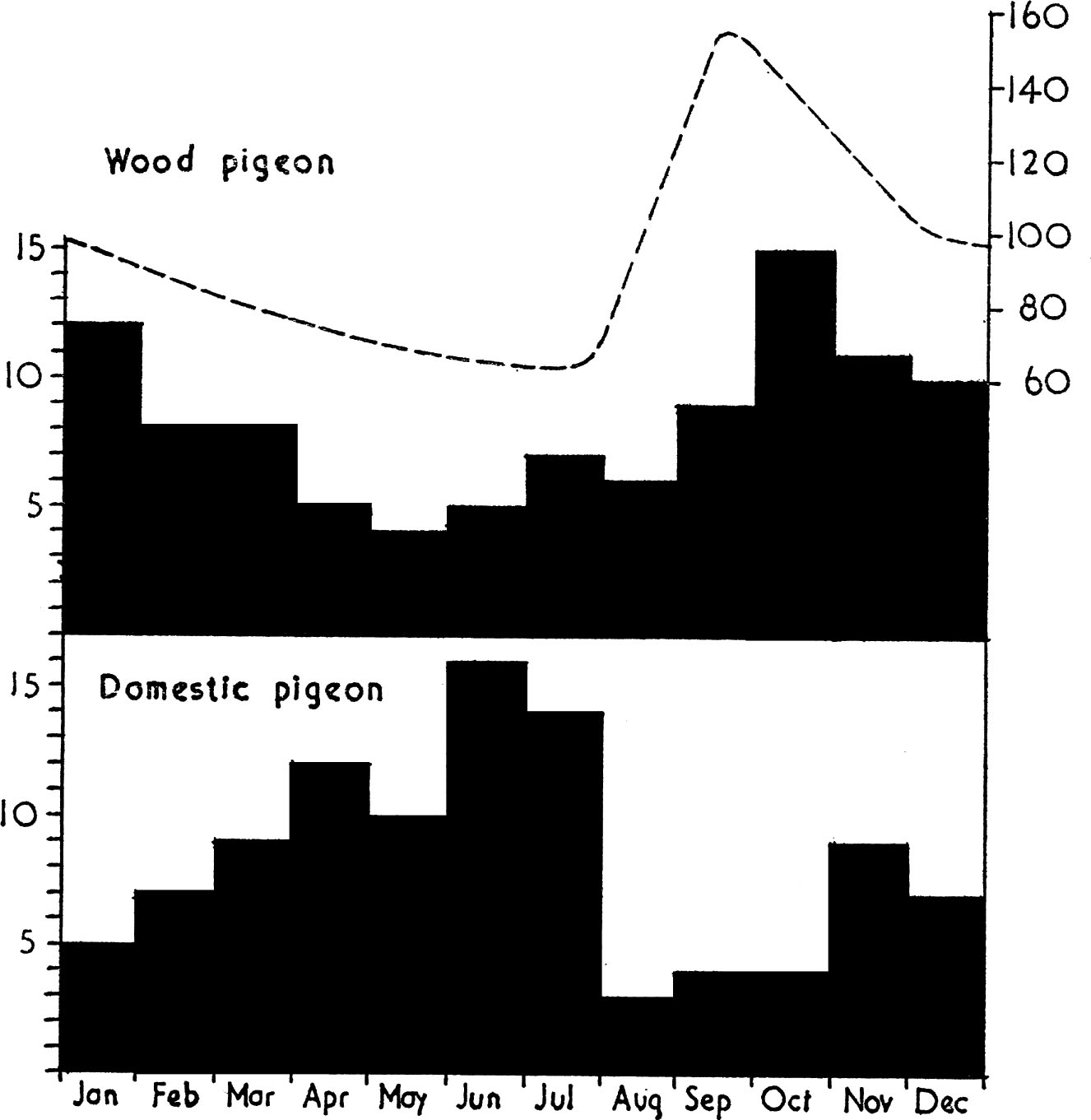

FIG. 13. Seasonal changes in the number of wood-pigeons (top figure) or domestic pigeons (lower figure) in the diet of the goshawk in Germany. The dotted line is based on Murton, Westwood & Isaacson 1964 and represents seasonal changes in the population size of the wood-pigeon. Goshawks take more pigeons when the population size of their prey is swollen by a post-breeding surplus of juveniles, domestic pigeons having their peak breeding season earlier than wood-pigeons. (Based on data in Brüll 1964).

Table 3 summarises the diet of two other birds of prey, the sparrowhawk and goshawk. Apart from demonstrating how two closely related species differ in their food requirements, enabling them to co-exist in the same deciduous woodland habitat without competition, the table shows the importance of the wood-pigeon in the diet of the goshawk. The fact that the goshawk is slightly larger than the peregrine and is also a woodland species accounts for its ability to take those larger pigeons which the peregrine rarely utilises. Many people have suggested that the goshawk should be encouraged to settle in Britain to help control the wood-pigeon population, but there is no evidence that it would take a sufficient toll to be effective, for the same reasons that eagles and harriers do not control grouse numbers. Fig. 13 supports this view by showing the proportion of wood-pigeons in the prey of goshawks at different seasons, against seasonal changes in wood-pigeon numbers. Clearly wood-pigeons are mostly eaten at the end of the breeding season when many juveniles are available, and in mid-winter when population size is still high. In spring, when the goshawk could potentially depress population size below normal – and hence really control numbers – it turns to other more easily captured prey. In contrast, feral and domestic pigeons breed earlier in the year and have a population peak in June; this is when they are most often caught by goshawks.

Neolithic husbandmen were doubtless familiar with the presence of ravens and crows near their domestic animals, long before biblical shepherds were tending their flocks aware that these birds were a potential menace to a young or weakly animal – the eye that mocketh at his father … the ravens of the valley shall pick it out (Proverbs 30: 17). Predacious habits and black plumage, burnt by the fires of hell, long ago made the crows prophets of disaster. A suspicion of such augury still persists among those who today think it appropriate to hang corvids and birds of prey on some barbed wire fence or makeshift gibbet; while these crucifixions may well release human frustrations, they do nothing whatever to deter the survivors (see Chapter 12).

Ravens are no longer widely distributed throughout Britain as they were in medieval and even more recent times, but there are still frequent complaints from hill farmers and shepherds in parts of Wales, northern England and Scotland that ravens, and hooded or carrion crows, sometimes kill or maim lambs and even weakly ewes. According to Bolam (1913) sheep, mostly in the form of carrion, comprise the major part of the diet of ravens in Merionethshire, sheep remains being found at least three times more frequently in castings than remains of any other food item (these including rabbits, rats, voles and mice, moles, birds, seashore and other invertebrates, snails and large beetles and some vegetable remains of cereals and tree fruits). Similarly, E. Blezard (quoted by D. Ratcliffe 1962) found sheep remains in over half the castings he examined from birds in northern England and southern Scotland, the next most important item being rabbit, which occurred in only a quarter of the castings. The examination of castings probably underestimates the importance of rapidly digested invertebrates or vegetable foods, but it is clear that sheep (probably as carrion) are an important food source, although the raven, like the crow, is very much an omnivore and carrion feeder. There is no reason to doubt that the raven had similar food habits in the past, when it occurred throughout lowland Britain; in fact, we know that shepherds in Suffolk around 1850 were bitterly hostile to the bird – ‘five were among Mr Roper’s sheep at Thetford in August 1836’. Like the buzzard, the raven was a reasonably common breeder in Norfolk and Suffolk until about 1830, but it declined markedly thereafter, coincident with the rise of intensive keepering, and it had vanished by the end of the nineteenth century. While continued persecution was doubtless responsible for the final elimination of the bird, and was also probably responsible for making the carrion crow very rare in the second half of the nineteenth century, other factors doubtless contributed to the initial decline. Loss of carrion is usually given as the cause, and it seems likely that it was specifically the loss of sheep carrion that was responsible. In Norfolk and Suffolk this coincided with the period of active enclosure, particularly that of waste land and sheep walks from 1800 to the mid-nineteenth century. According to Arthur Young, half Norfolk yielded nothing but sheep feed until the close of the eighteenth century, when with enormous speed – enclosure was mostly achieved in twenty years – the land was covered with fine barley, rye and wheat. The rapidity with which enclosure was completed is manifested in west Norfolk by straight roads and compact villages, the result of planning on a large scale, whereas in the east of the county the winding lanes, isolated churches, farms and homesteads derive from centuries of slow economic evolution.