Полная версия

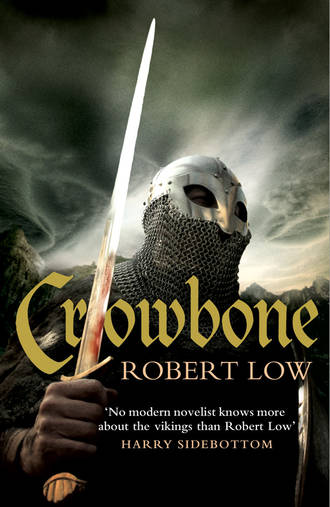

Crowbone

But it was all posturing, Crowbone thought. Vladimir was pleased his brother was dead and would have contrived a way of doing it himself if Crowbone had not axed the problem away.

The real reason for the Prince of Kiev’s ire was that Crowbone’s name was hailed just as frequently as Vladimir’s now – and that equality could not be allowed to continue. It was just a move in the game of kings.

Crowbone fastened his scowl on the Bear-Slayer. A legend, this jarl of the Oathsworn – Crowbone was one of them and so Orm was his jarl, which fact he tried hard not to let scrape him. He owed Orm a great deal, not least his freedom from thralldom.

Eight years had passed since then. Now the boy Orm had rescued was a tall, lithe youth coming into the main of his years, with powerful shoulders, long tow-coloured braids heavy with silver rings and coins, and the beginning of a decent beard. Yet the odd eyes – one blue as old ice, the other nut-brown – were blazing and the lip still petulant as a bairn’s.

‘Vladimir could no more rule with his brother alive than I can fart silver,’ Crowbone answered, the pout vanishing as suddenly as it had appeared. ‘When he has had time to think of this, he will thank me.’

‘Oh, he thanks you, right enough,’ Finn offered, wincing as he planted one buttock on a bench. ‘It is forgiveness he finds hard.’

Crowbone ignored the cheerful Finn, who was clearly enjoying this quarrel among princes. Instead, he studied Orm, seeing the harsh lines at the mouth which the neat-trimmed beard did not hide, just as the brow-braids did not disguise the fret of lines at the corners of the eyes, nor the scar that ran straight across the forehead above the cool, sometimes green, sometimes blue eyes. The nose was skewed sideways, his cheeks were dappled with little poxmark holes, his left hand was short three fingers, and he limped a little more than he had the year before.

A hard life, Crowbone knew and, when you could read the rune-marks of those injuries, you knew the saga-tale of the man and the Oathsworn he led.

Unlike Finn there was no grey in Orm Bear-Slayer yet, but they were both already old, so that a trip from Kiev, sluiced by Baltic water that still wanted to be ice, was an ache for the pair of them. Worse still, they had snugged the ship up in Hedeby and ridden across the Danevirke to Hammaburg, which fact Finn mentioned at length every time he shifted his aching cheeks on a bench.

‘Did the new Prince of Kiev send you, then?’ Crowbone asked and looked at the casket on the table. Silver full it was, including some whole coins and full-weight minted ones at that. Brought with ceremony by Orm and placed pointedly in front of him.

‘Is this his way of saying how sorry he is for threatening to stake me? An offering of gratitude for fighting him on to the throne of Kiev and ridding him of his rival?’

‘Not likely,’ Orm declared simply, unmoved by Crowbone’s attempt at bluster.

‘You were ever over-handy with an axe and a forehead, boy,’ Finn added and there was no grin in his voice now. ‘I warned you it would get you into trouble one day – this is the second time you have annoyed young Vladimir with it.’

The first time, Crowbone had been nine and fresh-released from slavery; he had spotted his hated captor across the crowded market of Kiev and axed him in the forehead before anyone could blink. That had put everyone at risk and neither Orm nor Finn would ever forget or forgive him for it.

Crowbone knew it, for all his bluster.

‘So whose silver is this, then?’ Crowbone demanded, knowing the answer before he spoke.

Orm merely looked at him, then shrugged.

‘I have a few moonlit burials left,’ he declared lightly. ‘So I bring you this.’

Crowbone did not answer. Moonlit buried silver was a waste. Silver was for ships and men and there would never be enough of it in the whole world, Crowbone thought, to feed what he desired.

Yet he knew Orm Bear-Slayer did not think like this. Orm had gained Odin’s favour and the greatest hoard of silver ever seen, which was as twisted a joke as any the gods had dreamed up – for what had the Oathsworn done with it after dragging it from Atil’s howe back into the light of day? Buried it in the secret dark again and agonised over having it.

Because Crowbone owed the man his life, he did not ever say to Orm what was in his heart – that Orm was not of the line of Yngling kings and that he, Olaf, son of Tryggve, by-named Crowbone, had the blood in him. So they were different; Orm Bear-Slayer would always be a little jarl, while Olaf Tryggvasson would one day be king in Norway, perhaps even greater than that.

All the same, Crowbone thought moodily, Asgard is a little fretted and annoyed over the killing of Yaropolk, which, perhaps, had been badly timed. It came to him then that Orm was more than a little fretted and annoyed. He had travelled a long way and with few companions at some risk. Old Harald Bluetooth, lord of the Danes, had reasons to dislike the Oathsworn and Hammaburg was a city of Otto’s Saxlanders, who were no friends to Jarl Orm.

‘Not much danger,’ Orm answered with an easy smile when Crowbone voiced this. ‘Otto is off south to Langabardaland to quarrel with Pandulf Ironhead. Bluetooth is too busy building ring-forts at vast expense and with no clear reason I can see.’

To stamp his authority, Crowbone thought scathingly, as well as prepare for another war with Otto. A king knows this. A real jarl can understand this, as easy as knowing the ruffle on water is made by unseen wind – but he bit his lip on voicing that. Instead, he asked the obvious question.

‘Do you wish me to find someone to take my place?’

A little more harshly said than he had intended; Crowbone did not want Orm thinking he was afraid, for finding a replacement willing to take the Oath was the only way to safely leave the Oathsworn. There were two others – one was to die, the other to suffer the wrath of Odin, which was the same.

‘No,’ Orm declared and then smiled thinly. ‘Nor is this a gift. I am your jarl. I have decided a second longship is needed and that you will lead the crew of it. The silver is for finding a suitable ship. You have the men you brought with you from Novgorod, so that is a start on finding a crew.’

Crowbone said nothing, while the wind hissed wetly off the sea and rattled the loose shutters. Finn watched the pair of them – it was cunning, right enough; there was not room on one drakkar for the likes of Orm and a Crowbone growing into his power and wyrd, yet there were benefits still for the pair of them if Crowbone remained one of the Oathsworn. Perhaps the width of an ocean or two would be enough to keep them from each other’s throats.

Crowbone knew it and nodded, so that Finn saw the taut lines of the pair of them ease, the hackles drift downwards. He shifted, grinned and then grunted his pleasure like a scratching walrus.

‘Where are you bound from here?’ Crowbone asked.

‘Back to Kiev,’ Orm declared. ‘Then the Great City. I have matters there. You?’

Crowbone had not thought of it until now and it came to him that he had been so tied up with Vladimir and winning that prince his birthright that he had not considered anything else. Four years he had been with Vladimir, like a brother … he swallowed the flaring anger at the Prince of Kiev’s ingratitude, but the fire of it choked him.

‘Well,’ said Orm into the silence. ‘I have another gift, of sorts. A trader who knows me, called Hoskuld, came asking after you. Claims to have come from Mann with a message from a Christ monk there. Drostan.’

Crowbone cocked his head, interested. Orm shrugged.

‘I did not think you knew this monk. Hoskuld says he is one of those who lives on his own in the wilderness and has loose bits in the inside of his thought-cage. It means nothing to me, but Hoskuld says the priest’s message was a name – Svein Kolbeinsson – and a secret that would be of worth to Tryggve’s son, the kin of Harald Fairhair.’

Crowbone looked from Orm to Finn, who spread his hands and shrugged.

‘I am no wiser. Neither monk nor name means anything to me and I am a far-travelled man, as you know. Still – I am thinking it is curious, this message.’

Enough to go all the way to Mann, Crowbone wondered and had not realised he had voiced it aloud until Orm answered.

‘Hoskuld will take you, you do not need to wait until you have found a decent ship and crew,’ he said. ‘You have six men of your own and Hoskuld can take nine and still manage a little cargo – with what you pay him from that silver, it is a fine profit for him. Ask Murrough to go with you, since he is from that part of the world and will be of use. You can have Onund Hnufa, too, if you want, for you might need a shipwright of his skill.’

Crowbone blinked a little at that; these were the two companions who had come with Orm and Finn and both were prizes for any ship crew. Murrough macMael was a giant Irisher with an axe and always cheerful. Onund Hnufa, was the opposite, a morose oldster who could make a longship from two bent sticks, but he was an Icelander and none of them cared for princes, particularly if they came from Norway. Besides that, he had all the friendliness of a winter-woken bear.

‘One is your best axe man. The other is your shipwright,’ he pointed out and Orm nodded.

‘No matter who pays us, we are out on the Grass Sea,’ he answered, ‘fighting steppe horse-trolls, without sight of water or a ship. Murrough would like a sight of Ireland before he gets much older and you are headed that way. Onund does not like looking at a land-horizon that gets no closer, so he may leap at this chance to return to the sea.’

He stared at Crowbone, long and sharp as a spear.

‘He may not, all the same. He does not care for you much, Prince of Norway.’

Crowbone thought on it, then nodded. Wrists were clasped. There was an awkward silence, which went on until it started to shave the hairs of Crowbone’s neck. Then Orm cleared his throat a little.

‘Go and make yourself a king in Norway,’ he said lightly. ‘If you need the Oathsworn, send word.’

As he and Finn hunched out into the night and the squalling rain, he flung back over his shoulder, ‘Take care to keep the fame of Prince Olaf bright.’

Crowbone stared unseeing at the wind-rattling door long after they had gone, the words echoing in him. Keep the fame of Prince Olaf bright – and, with it, the fame of the Oathsworn, for one was the other.

For now, Crowbone added to himself.

He stirred the silver with a finger, studying the coins and the roughly-hacked bits and pieces of once-precious objects. Silver dirham from Serkland, some whole coins from the old Eternal City, oddly-chopped arcs of ring, sharp slivers of coin wedges, cut and chopped bar ingots. There was even a peculiarly shaped piece that could have been part of a cup.

Cursed silver, Crowbone thought with a shiver, if it came from Orm’s hoard, which came from Atil’s howe. Before that the Volsungs had it, brought to them by Sigurd, who killed the dragon Fafnir to possess it; the history of these riches was long and tainted.

It had done little good to Orm, Crowbone thought. He had been surprised when Orm had announced that he was returning to Kiev, for the jarl had been brooding and thrashing around the Baltic, looking for signs of his wife, Thorgunna, for some time.

She had, Crowbone had heard, turned her back on her man, her life, the gods of Asgard and her friends to follow a Christ priest and become one of their holy women, a nun.

That had been part of the curse of Atil’s silver on Orm. The rest was the loss of his bairn, born deformed and so exposed – the act which had so warped Thorgunna out of her old life – and the death of the foster-wean Orm had been entrusted with, who happened to be the son of Jarl Brand, who had gifted the steading at Hestreng to Orm.

In one year, the year after Orm had gained the riches of Atil’s tomb, the curse on that hoard had taken his wife, his newborn son, his foster-son, his steading, his friendship with the mighty and a good hack out of his fair fame.

Crowbone studied the dull, winking gleam of that pile and wondered how much of it had come from the Volsung hoard and how bad the curse was.

Sand Vik, Orkney, at the same time …

THE WITCH-QUEEN’S CREW

The wind blew from the north, hard and cold as a whore’s heart so that clouds fled like smoke before it and the sun died over the heights of Hoy. The sea ran grey-green and froth flew off the waves, rushing like mad horses to shatter and thunder on the headlands, the undertow smacking like savouring lips until the suck was crushed by another wild-horse rush.

The man shivered; even the thick walls of this steading did not seem solid enough and he felt the bones of the place shudder up through his feet. There was comfort here, all the same, he saw, but it was harsh and too northern, even for him – the room was murky with reek because the doors were shut against the weather and the wind swooped in through the hearthfire smokehole and simply danced it round the dim hall, flaring the coals and flattening flame. It made the eyes of the storm-fretted black cat glow like baleful marshlights.

A light appeared, seeming to float on its own and flickering in the wild air, so that the man shifted uneasily, for all he was a fighting man of some note, and hurriedly brought up a hand to cross himself.

There was a chuckle, a dry rustle of sound like a rat in old bracken and the night crawled back from the flame, revealing gnarled driftwood beams, a hand on the lamp ring, blackness beyond.

Closer still and he saw an arm but only knew it from the dark by the silver ring round it, for the cloth on it was midnight blue. Another step and there was a face, but the lamp blurred it; all the man could see clearly was the hand, the skin sere and brown-pocked, the fingers knobbed.

That and the eyes of her, which were bone needles threading the dark to pierce his own.

‘Erling Flatnef,’ said the dry-rustle voice, rheumed and thick so that the sound of his own name raised the hackles on his arm. ‘You are late.’

Erling’s cheeks felt stiff, as if he had been staring into a white blizzard, yet he summoned words from the depth of himself and managed to spit them out.

‘I waited to speak with my lord Arnfinn,’ he said and the sound of his voice seemed sucked away somehow.

‘Just so – and what did the son of Thorfinn Jarl have to say?’

The moth-wing hiss of her voice was slathered with sarcasm, for which Erling had no good reply. The truth was that the four sons of Thorfinn who now ruled Orkney were as much in thrall to this crumbling ruin, Gunnhild, Mother of Kings, as their father had been. Arnfinn, especially, was hag-cursed by it and had merely brooded his eyes into the pitfire and then waved Erling on his way without a word, trying not to look at his wife, Ragnhild, who was Gunnhild’s daughter.

Erling’s silence gave Gunnhild all the answer she needed. As her face loomed out from behind the blurring light of the lamp he was unable even to cross himself, was paralysed at the sight of it. Whatever The Lady wanted, she would get; not for the first time, Erling pitied the Jarls of Orkney and the mother-in-law they wore round their necks.

Not that it was an ugly face, aged and raddled. The opposite. It was a face with skin that seemed soft as fine leather with only a tracery of lines round the mouth, where the lips were a little withered. A harsh line or two here and there on it, which only accentuated the heart-leaping beauty that had been there in youth. Gunnhild wanted to smile at the sight of him, but knew that would crack the artifice like throwing a stone on thin ice. She used her face as a weapon and clubbed him with it.

‘I had a son called Erling,’ she said and Erling stiffened. He knew that – Haakon Jarl had killed him. For a wild moment of panic Erling wondered if she sought to raise the dead son and needed to steal the name …

‘I have a task for you, Flatnose,’ she said in her ruin of a voice. ‘You and my last, useless son Gudrod and that Tyr-worshipping boy of yours – what is his name?’

‘Od,’ Erling managed and mercifully Gunnhild slid away from him, back into the shadows.

‘Listen,’ she said and laid the meat of it out, a long rasp of wonder in that fetid dark. The revelations left him shaking, wondering how she had discovered all this, awed at the rich seidr magic she still commanded – the gods knew how old she was, yet still beautiful and still a power.

Later, as he stumbled from the hall, the rain and battering wind were as much of a relief as goose-grease on a burn.

TWO

The coast of Frisia, a week later …

CROWBONE’S CREW

IT was no properly straked, oak-keeled drakkar, but the Or-skreiðr was a good ship, a sturdy, fat-waisted knarr with scarred planks and the comfort of ship-luck. It had carried the trader safely from Dyfflin to Hammaburg and elsewhere – even back to the trader’s home in Iceland. Hoskuld boasted of its prowess as it hauled Crowbone and his Chosen Men out of Hammaburg to the sea, then west along the coast. The Or-skreiðr, Swift-Gliding, was Hoskuld’s pride.

‘Even when Aegir of the waters is splashing about in the worst way,’ he declared, ‘I have never had a moment’s unease.’

Crowbone’s eight Oathsworn, jostling for sea-chest space with the crew and the cargo of hoes and mattocks and kegged fish, found little humour in this, though some gave dutiful laughs. But not Onund.

‘You should not dangle this stout ship in front of the Norns, like a worm on a hook,’ Onund growled morosely to Hoskuld. ‘Those Sisters love to hear the boasts of men – it makes them laugh.’

Crowbone said nothing, for he knew Onund had sourness seeped into him, for all he had agreed to this voyage. The other men were less frowning about matters. Murrough macMael was going back to Mann and possibly Ireland and that pleased him; the others – Gjallandi the skald, Rovald Hrafnbruder, Vigfuss Drosbo, Kaetilmund, Vandrad Sygni and Halfdan Knutsson – were happy to be going anywhere with the Prince Who Would Be King. They were all seasoned Swedes and half-Slavs who had been down the cataracts from Kiev with the silk traders at least once and had sailed up and down the Baltic with Crowbone, raiding in the name of Vladimir, Prince of Novgorod and now Kiev.

Ring-coated most of them, exotic in fat breeks and big boots and fur-trimmed hats with silver wire designs, they swaggered and bantered idly in the fat-waisted little knarr and made Hoskuld and his working men scowl.

‘How do we know their worth?’ one seaman grumbled in Crowbone’s hearing. ‘Who decided on these instead of a decent cargo?’

‘They think we are just barrels of salt cod,’ Gjallandi announced, appearing suddenly at Crowbone’s ear, ‘while your new Chosen Men believe it is a day’s sail, with a bit of sword-waving at the end of it and yourself crowned king of Norway, no doubt. All will find the truth of matters, soon enough.’

He was shaking his head, which made all those who did not know him laugh, for he was not the figure of a raiding man. He was a middling man in most respects save two – his head and his voice.

His head was large, with a chin like a ship’s prow and two full, beautiful lips in the centre of it, surrounded by a neat-trimmed fringe of moustache and beard. The hair on his head was marvellously copper-coloured, but galloping back over his forehead on either side of his ears; when the wind blew it stuck straight out behind him like spines. Murrough said it was not his hair that was receding but his head growing from all the lore he stuffed in it.

That lore and his voice had made his fortune, all the same, first as skald to a jarl called Skarpheddin and then to Jarl Brand. He had left Brand after arguing that it was not right to come down so hard on Jarl Orm for the loss of Jarl Brand’s son – which, according to Murrough and others, showed how Gjallandi’s voice sometimes worked before his thought-cage did.

Now he had come with Crowbone because, he said, Crowbone had more saga in him and the tale of the exiled Prince of Norway reclaiming his birthright was too good to miss. Crowbone had joined in the good-natured laughter, but secretly liked the idea of having someone spread his fame; the thought was as warming a comfort as a hearthfire and a horn of ale.

‘The crowning will come in time,’ Crowbone answered, loud enough for everyone to hear. ‘Until then, there are ships and men waiting to join us.’

‘No doubt,’ said the steersman whose name was Halk and his Norse was strange and lilting. ‘Do they know you are coming?’

His voice had a laugh in it which removed any sting and Crowbone smiled back at him.

‘If you know where you are going,’ he replied, ‘then – there they will all be.’

It was clear that Hoskuld had told his men nothing much, which was not sensible in a tight crew of six who depended on each other and the trade they made. Crowbone did not much trust Hoskuld, for all he had come from Mann to deliver his mysterious message – without pay, no doubt, for Christ monks were notoriously empty-pursed.

‘For the love of God,’ Hoskuld had replied when Crowbone had asked the why of this and his face, battered by wind and wave into something like a headland with eyes, gave away nothing. His men said even less, keeping their eyes and hands on work, but Crowbone felt Hoskuld’s lie like a chill haar on his skin. Yet Hoskuld was a friend of Orm and that counted for much.

Crowbone sat and watched the land slip sideways past him while the sea rose and fell, dark, glassy planes heaving in a slow, breathing rhythm.

He watched the gulls. Hoskuld never got far enough from the land to lose them and Crowbone listened to them scream to each other of finding something that moved and promised fish. One perched on the mast spar, heedless of the sail’s great belly and Crowbone watched this one more carefully than the others. He felt the familiar tightening of the skin on his arms and neck; something was happening.

The crew of the Or-skreiðr coiled lines, bailed, reefed sail, took the steering oar and stared at Crowbone and his eight men. He could almost feel their dislike and their distrust and, above all, their fear. Here were the plunderers, pillagers and pagans that peaceful Christ-anointed traders, farmers of the sea-lanes, could do without as they ploughed up and down from port to port.

Here were red murderers, sitting on their sea-chests, talking in their mush-mouthed East Norse way – made worse by all the time spent with Slavs – and eyeing up the crew with almost complete indifference when not with sardonic smiles at watching men work while they stayed idle.

Crowbone knew his eight Chosen well, knew who was more Svear than Slav, who had washed that weekday, who doubted their own prowess.

Young men – well, all but Onund – hard men, who had all, without showing fear, taken that hard oath of the Oathsworn: we swear to be brothers to each other, bone, blood and steel, on Gungnir, Odin’s spear we swear, may he curse us to the Nine Realms and beyond if we break this faith, one to another.

Crowbone had taken it when he was too young for chin hair, driven to it as those desperate and lost in the dark will run to a fire, even if it risks a scorching. He had kin somewhere, sisters he had never seen – but mother, father, guardian uncle were all dead and Orm Bear-Slayer of the Oathsworn was the nearest thing he had to any of the three.

He watched his Chosen Men. Only Onund knew what the Oath meant, for he had taken it long enough ago to have marked the warp of it on his life. Most of the others would come to know just what they had sworn, but for now they were all grins and wild beards in every colour save grey, laughing and boasting easily, one to the other.