Полная версия

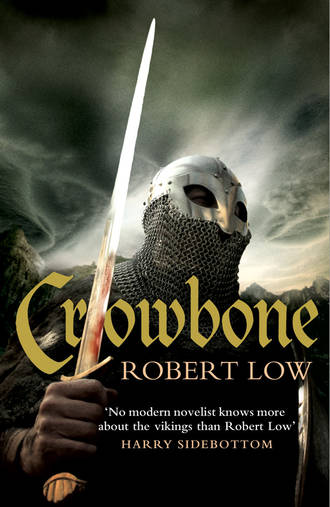

Crowbone

ROBERT LOW

Crowbone

To my wife, Kate,

who keeps my eyes on the real prize

In the hilt is fame.

In the haft is courage,

In the edge is fear.

Lay of Helgi Hjörvarðsson

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Map

Prologue

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Epilogue

Historical Note

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Robert Low

Copyright

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

Finnmark, A.D. 981

THEIR skin was already slack and waxen yet unsettling, with meltwater frozen from their final cooling beaded like new sweat. Black and orpiment bruising, red wounds gaping like lipless mouths, black blood thick as porridge crusting in the cold.

One face seemed to be looking at everyone who looked at it, a bewildered question frozen in the glassed eyes. His knuckles were clenched so tight on his belly that the rough pelt he wore oozed between fingers clamped on either side of the great gash, as if trying to force it shut on the blue snakes coiling from it. His hair was wild and uncombed and his nose needed wiping.

Too late for all of that, Crowbone was thinking.

They were tough, these dark little Sami from the snow hills, feared even by the Norse from Gjesvaer, who hunted whale and walrus and ice bears over the northern floes. They knew that the Sami could stalk a man and he would never know it until the bone tip of an arrow came out of his heart.

Even in a stand-up fight they are killing us, Crowbone thought, carving us like chips off a great tree. Men lay not far off, arms folded on their breasts and faces covered by cloaks. Men of skill and wit, gone from boasts and laughter to sacks of clothing, laid out like fresh-cut logs and just as stiff in the cold.

As for the Sami, they had now fought these mountain hunters too many times, but this was the first time they had seen so many of them dead in the one place. The crew moved among them silently, save for a muttered growl here and there, peered and prodded, knelt now and then to search in the blood and splintered bone. They were trying hard to ignore the strangeness of these beast-masked warriors and all the old fear-tales of Sami wizards.

It was Murrough, cleaning the great hook-bearded Dal Cais axe with one of their skin masks, who gave voice to all their fears, as he squinted at one lolling body and nudged it with his foot.

‘Sure,’ he said, ‘and I killed this one yesterday, so I did.’

ONE

Island of Mann, A.D. 979

THREE sheltered in the fish-reeked dim of the keeill, cramped up and feeling the cold seep into their bones – but only one of them did not care, for he was dying. Though truth was, Drostan thought, glancing sideways at the red-glowed beak-face of the Brother who lived here, perhaps this priest cares even less than the dying.

‘I am done, brother,’ said Sueno and the husked whisper of him jerked Drostan back to where his friend and brother in Christ lay, sweat sheening his face in the faint glow from the fish-oil light.

‘Nonsense,’ Drostan lied. ‘When the storm clears tomorrow we will go down to the church at Holmtun and get help there.’

‘He will never get there,’ said the priest, voice harsh as the crow dark itself and bringing Drostan angrily round.

‘Whisht, you – have you so little Christian charity in you?’

There was a gurgle, which might have been a laugh or a curse, and suddenly the hawk-face was thrust close, so close that Drostan bent backwards away from it. It was not a comfort, that face. It had greasy iron tangles of hair round it, was leached of moisture so that it loomed like a cracked desert in the dark, all planes and shadows; the jaws clapped in around the few teeth in the mouth, which made black runestones when he spoke.

‘I lost it,’ he mushed, then his glittering priest eyes seemed to glass over and he rose a little and moved away to tend the poor fire, bent-backed, a rolling gait with a bad limp.

‘I lost it,’ he repeated, shaking his head. ‘Out on the great white. It lies there, prey to wolves and foxes and the skin-wearing heathen trolls – but no, God will keep it safe. I will find it again. God will keep it safe.’

Shaken, Drostan gathered himself like a raggled cloak. He knew of this priest only by hearsay and what he had heard had not been good. Touched, they said. A pole-sitter who fell off, one or two claimed with vicious humour. Foreign. This last Drostan now knew for himself, for the man’s harsh voice was veined with oddness.

‘God grant you find it soon and peace with it, brother,’ Drostan intoned piously, through his gritted teeth.

The hawk-face turned.

‘I am no brother of yours, Culdee,’ he said, his voice a sneer. ‘I am from Hammaburg. I am a true follower of the true church. I am monk and priest both.’

‘I am merely a humble anchorite of the Cele Dei, as is the poor soul here. Yet here we all are,’ answered Drostan, irritated. ‘Brother.’

The rain hissed on the stone walls, driving damp air in to swirl the scent of wrack round in the fish-oil reek. The priest from Hammaburg looked left, right and then up, as if seeking God in the low roof; then he smiled his black-rotted smile.

‘It is not a large hall,’ he admitted, ‘but it serves me for the while.’

‘If you are not one of us,’ Drostan persisted angrily while trying to make Sueno more comfortable against the chill, ‘why are you here in this place?’

He sat back and waved a hand that took in the entire keeill with it, almost grazing the cold stone of the rough walls. A square the width of two and half tall men, with a roof barely high enough to stand up in. It was what passed for a chapel in the high lands of Mann, and Drostan and Sueno each had their own. They brought the word of God from the Cele Dei – the Culdee – church of the islands to any who flocked to listen. They were cenobites, members of a monastic community who had gone out in the world and become lonely anchorites.

But this monk was a real priest from Hammaburg, a clerk regular who could preach, administer sacrament and educate others, yet was also religious in the strictest sense of the word, professing solemn vows and the solitary contemplation of God. It stung Drostan that this strange cleric claimed to be the united perfection of the religious condition – and did not share the same beliefs as the Cele Dei, nor seem to possess any Christian charity.

Drostan swallowed the bitter bile of it, flavoured with the harsh knowledge that the priest was right and Sueno was dying. He offered a silent apology to God for the sin of pride.

‘I wait for a sign,’ the Hammaburg priest said, after a long silence. ‘I offended God and yet I know He is not done with me. I wait for a sign.’

He shifted a little to ease himself and Drostan’s eyes fell to the priest’s foot, which had no shoe or sandal on it because, he saw, none would have fitted it. Half of it was gone; no toes at all and puckered flesh to the instep. It would be a painful thing to walk on that without aid of stick or crutch and Drostan realised then that this was part of the strange priest’s penance while he waited for a sign.

‘How did you offend God?’ he asked, only half interested, his mind on Sueno’s suffering in the cold.

There was silence for a moment, then the priest stirred as if from some dream.

‘I lost it,’ he said simply. ‘I had it in my care and lost it.’

‘Christian charity?’ Drostan asked without looking up, so that he missed the sharp glitter of anger sparking in the priest’s eyes, followed by that same dulling, as if the bright sea had been washed by a cloud.

‘That I lost long since. The Danes tore that from me. I had it and I lost it.’

Drostan forgot Sueno, stared at the hawk-faced cleric for a long moment.

‘The Danes?’ he repeated, then crossed himself. ‘Bless this weather, brother, that keeps the Dyfflin Danes from us.’

The Hammaburg priest was suddenly brisk and attentive to the fire, so that it flared briefly, before the damp wood fought back and reduced it once more to a mean affair of woodsmoke reek and flicker.

‘I had it, out on the steppes of Gardariki in the east,’ he went on, speaking to the dark. ‘I lost it. It lies there, waiting – and I wait for a sign from God, who will tell me that He considers me penance-paid for my failure and now worthy to retrieve it. That and where it is.’

Drostan was millstoned by this. He had heard of Gardariki, the lands of the Rus Slavs, but only as a vague name for somewhere unimaginably far away, far enough to be almost a legend – yet here was someone who had been there. Or claimed it; the hermit-monk of this place, Drostan had been told, was head-sick.

He decided to keep to himself the wind-swirl of thoughts about his journey here, half carrying Sueno, whom he had visited and found sick, so resolving to take him down to the church where he could be made comfortable; he would say nothing of how God had brought them here, about the storm that had broken on them. It was then God sent the guiding light that had led them here, to a place so thick with holy mystery they had trouble breathing.

The cynical side to Drostan, all the same, whispered that it was the fish oil and woodsmoke reek that made breathing hard. He smiled in the dark; the cynical thought was Sueno’s doing, for until they had found themselves only a few miles of whin and gorse apart, each had been alone and Drostan had never questioned his faith.

He had discovered doubt and questioning as soon as he and Sueno had started in to speaking, for that seemed to be the older monk’s way. For all that he wondered why Sueno had taken to the Culdee life up there on the lonely, wind-moaning hills, Drostan had never resented the meeting.

There was silence for a long time, while the rain whispered and the wind moaned and whistled through the badly-daubed walls. He knew the Hammaburg priest was right and Sueno, recalcitrant old monk that he was, was about to step before the Lord and be judged. He prayed silently for God’s mercy on his friend.

The priest from Hammaburg sat and brooded, aware that he had said too much and not enough, for it had been a time since he had spoken with folk and even now he was not sure that the two Culdees were quite real.

There had been an eyeblink of strangeness when the two had stumbled in on him out of the rain and wind and it had nothing to do with their actual arrival – he had grown used to speaking with phantoms. Some of them were, he knew, long dead – Starkad, who had chased him all down the rivers of Gardariki and into the Holy Land itself until his own kind had slaughtered him; Einar the Black, leader of the Oathsworn and a man the Hammaburg priest hated enough to want to resurrect for the joy of watching him die again; Orm, the new leader and equally foul in the eyes of God.

No. The strangeness had come when the one called Drostan had announced himself, expecting a name in return. It took the priest from Hammaburg by surprise when he could not at once remember his own. Fear, too. Such a thing should not have been lost, like so many other things. Christian charity. Long lost to the Danes of the Oathsworn out on the Great White where the Holy Lance still lay among fox turds and steppe grasses. At least he hoped it was, that God was keeping it safe for the time it could be retrieved.

By me, he thought. Martin. He muttered it to himself through the stumps of his festering teeth. My name is Martin. My name is pain.

Towards dawn, Sueno woke up and his coughing snapped the other two out of sleep. Drostan felt a claw hand on his forearm and Sueno drew himself up.

‘I am done,’ he said, and this time Drostan said nothing, so that Sueno nodded, satisfied.

‘Good,’ he said, between wheezing. ‘Now you will listen more closely, for these are the words of a dying man.’

‘Brother, I am a mere monk. I cannot hear your Confession. There is a proper priest here …’

‘Whisht. We have, you and I, ignored that fine line up in the hills when poor souls came to us for absolution. Did it matter to them that they might as well have confessed their sins to a tree, or a stone? No, it did not. Neither does it matter to me. Listen, for my time is close. Will I go to God’s hall, or Hel’s hall, I wonder?’

His voice, no more than husk on the draught, stirred Drostan to life and he patted, soothingly.

‘Hell has no fires for you, brother,’ he declared firmly and the old monk laughed, brought on a fit of coughing and wheezed to the end of it.

‘No matter which gods take me,’ he said, ‘this is a straw death, all the same.’

Drostan blinked at that, as clear a declaration of pagan heathenism as he had heard. Sueno managed a weak flap of one hand.

‘My name, Sueno, is as close as these folk get to Svein,’ he said. ‘I am from Venheim in Eidfjord, though there are none left there alive enough to remember me. I came with Eirik to Jorvik. I carried Odin’s daughter for him.’

Sueno stopped and raised himself, his grip on Drostan’s arm fierce and hard.

‘Promise me this, Drostan, as a brother in Christ and in the name of God,’ he hissed. ‘Promise me you will seek out the Yngling heir and tell him what I tell you.’

He fell back and mumbled. Drostan wiped the spittle from his face with a shaking hand, unnerved by what he had heard. Odin’s daughter? There was rank heathenism, plain as sunlight on water.

‘Swear, in the name of Christ, brother. Swear, as you love me …’

‘I swear, I swear,’ Drostan yelped, as much to shut the old man up as anything. He felt a hot wash of shame at the thought and covered it by praying.

‘Enough of that,’ growled Sueno. ‘I have heard all the chrism-loosening cant I need in the thirty years since they dragged me off from Stainmore. Fucking treacherous bitch-fucks. Fucking gods of Asgard abandoned us then …’

He stopped. There was silence and wind hissed rain-scent through the wall cracks, making the woodsmoke and oil reek swirl chokingly. Sueno breathed like a broken forge bellows, gathered enough air and spoke.

‘Do not take this to the Mother of Kings. Not Gunnhild, his wife, Eirik’s witch-woman. Not her. She is not of the line and none of Eirik’s sons left to the bitch deserve to marry Odin’s daughter … Asgard showed that when the gods turned their faces from us at Stainmore.’

Drostan crossed himself. He had only the vaguest notions what Sueno was babbling, but he knew the pagan was thick in it.

‘Take what I tell you to the young boy, if he lives,’ Sueno husked out wearily. ‘Harald Fairhair’s kin and the true line of Norway’s kings. Tryggve’s son. I know he lives. I hear, even in this wild place. Take it to him. Swear to me …’

‘I swear,’ Drostan declared quietly, now worried about the blood seeping from between Sueno’s cracking lips.

‘Good,’ Sueno said. ‘Now listen. I know where Odin’s daughter lies …’

Forgotten in the dark, Martin from Hammaburg listened. Even the pain in his foot, that driving constant from toes that no longer existed – clearly part of the penance sent from God – was gone as he felt the power of the Lord whisper in the urgent, hissing, blood-rheumed voice of the old monk.

A sign, as sure as fire in the heavens. After all this time, in a crude stone hut daubed with poor clay and Christ hope, with a roof so low the rats were hunchbacked – a sign. Martin hugged himself with the ecstasy of it, felt the drool from his broken mouth spill and did not try to wipe it away. In a while, the pain of his foot came back, slowly, as it had when it thawed, gradually, after his rescue from the freeze of a steppe winter.

Agonising and eternal, that pain, and Martin embraced it, as he had for years, for every fiery shriek of it reminded him of his enemies, of Orm Bear-Slayer who led the Oathsworn, and Finn who feared nothing – and Crowbone, kin of Harold Fairhair of the Yngling line and true prince of Norway. Tryggve’s son.

There was a way, he thought, for God’s judgement to be delivered, for the return of what had been lost, for the punishment of all those who had thwarted His purpose. Now even the three gold coins, given to him by the lord of Kiev years since and never spent, revealed their purpose, and he glanced once towards the stone they were hidden beneath. A good hefty stone, that, and it fitted easily into the palm.

By the time the old monk coughed his blood-misted last at dawn, Martin had worked out the how of it.

Hammaburg, some months later …

Folk said it was a city to make you gasp, hazed with smoke and sprawling with hundreds of hovs lining the muddy banks and spilling backwards into the land. There were ships by the long hundred lying at wharfs, moored by pilings, or drawn up on the banks and crawling with men, like ants on dead fish.

There were warehouses, carts, packhorses and folk who all seemed to shout to be heard above the din of metalsmith hammers, shrieking axles and fishwives who sounded as like the quarrelling gulls as to be sisters.

Above all loomed the great timber bell tower of the Christ church, Hammaburg’s pride. In it sat a chief Christ priest called a bishop, who was almost as important as the Christ priest’s headman, the Pope, Crowbone had heard.

Cloaked in the arrogance of a far-traveller with barely seventeen summers on him, Crowbone was as indifferent to Hammaburg as the few men with him were impressed; he had seen the Great City called Constantinople, which the folk here named Miklagard and spoke of in the hushed way you did with places that were legend. But Crowbone had walked there, strolled the flower-decked terraces in the dreaming, windless heat of afternoon, where the cool of fountains was a gift from Aegir, lord of the deep waters.

He had swaggered in the surrounds of the Hagia Sophia, that great skald-verse of stone which made Hammaburg’s cathedral no more than a timber boathouse. There had been round, grey stones paving the streets all round the Hagia, Crowbone recalled, with coloured pebbles between them and doves who were too lazy to fly, waddling out from under your feet.

Here in Hammaburg were brown-robed priests banging bells and chanting, for they were hot for the cold White Christ here – so much so that the Danes had grown sick of Bishop Ansgar, Apostle of the North, burning the place out from underneath him before they sailed up the river. That was at least five score years ago, so that scarce a trace of the violence remained – and Crowbone had heard that Hammaburg priests still went out to folk in the north, relentless as downhill boulders.

Crowbone was unmoved by the fervour of these shaven monks for he knew that, if you wanted to feel the power of the White Christ, then Miklagard, the Navel of The World, was the place for it. The spade-bearded priests of the Great City perched on walls and corners, even on the tops of columns, shouting about faith and arguing with each other; everyone, it seemed to Crowbone, was a priest in Miklagard. There, temples could be domed with gold, yet were sometimes no more than white walls and a rough roof with a cross.

In Miklagard it was impossible to buy bread without getting a babble about the nature of their god from the baker. Even whores would discuss how many Christ-Valkeyrii might exist in the same space while pulling their shifts up. Crowbone had discovered whores in the Great City.

Hammaburg’s whores thought only of money. Here the air was thick with haar, like wet silk, and the Christ-followers sweated and knelt and groaned in fearful appeasement, for the earth had shifted and, according to some Englisc monks, a fire-dragon had moved over their land, a sure sign that the world would end as some old seer had foretold, a thousand years after the birth of their Tortured God. Time, it seemed, was running out.

Crowbone’s men laughed at that, being good Slav Rus most of them and eaters of horse, which made them heathen in the eyes of Good Christ-followers. If it was Rokkr, the Twilight, they all knew none of the Christ bells and chants would make it stop, for gods had no control over the Doom of all Powers and were wyrded to die with everyone else.

Harek, who was by-named Gjallandi, added that no amount of begging words would stop Loki squirming the earth into folds and yelling for his wife to hurry up and bring back the basin that stopped the World Serpent venom dripping on his face. He said this loudly and often, as befits a skald by-named Boomer, so that folk sighed when he opened his mouth.

Even though the men from the north knew the true cause of events, such Loki earth-folding still raised the hairs on their arms. Perhaps the Doom of all Powers was falling on them all.

Crowbone, for his part, thought the arrogance of these Christ-followers was jaw-dropping. They actually believed that their god-son’s birth heralded the last thousand years of the world and that everyone’s time was almost up. Twenty years left, according to their tallying; good Christ children born now would be young men when their own parents rose out of their dead-mounds and everyone waited to be judged.

Crowbone was hunched moodily under such thoughts, for he knew the whims of gods only too well; his whole life was a knife-edge balance, where the stirred air from a whirring bird’s wing could topple him to doom or raise him to the throne he considered his right. Since Prince Vladimir of Kiev had turned his face from him, the prospect seemed more doom than throne.

‘You should not have axed his brother,’ Finn Horsehead growled when Crowbone spat out this gloomy observation shortly after Finn had shown up with Jarl Orm.

Crowbone looked at the man, all iron-grey and seamed like a bull walrus, and willed his scowl to sear a brand on Finn’s face. Instead, Finn looked back, eyes grey as a winter sea and slightly amused; Crowbone gave up, for this was Finn Horsehead, who feared nothing.

‘Yaropolk’s death was necessary,’ Crowbone muttered. ‘How can two princes rule one land? Odin’s bones – had we not just finished fighting the man to decide who ruled in Kiev and all the lands round it? Vladimir’s arse would never have stayed long on the throne if brother Yaropolk had remained alive.’

He knew, also, that Vladimir recognised the reality of it, too, for all his threats and haughtiness and posturing about the honour of princes and truces – Odin’s arse, this from a man who had just gained a wife by storming her father’s fortress and taking her by force. Yaropolk, the rival brother, had to die, otherwise he would always have been a threat, real or imagined and, one day, would have been tempted to try again.

None of which buttered up matters any with Vladmir, who had turned his back on his friend as a result.

‘There had been fighting, right enough,’ answered Orm quietly, moving from the shadows of the room. ‘But a truce and an agreement between brothers marked the end of it – at which point you axed Yaropolk between the eyes.’