Полная версия

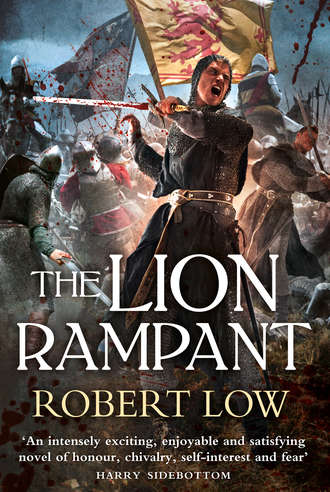

The Lion Rampant

Doña Beatriz stood, apart from the delight and shadowed by Piculph, watching Pegy and the two stupid brothers attending to the giant Islesman. She was frowning at what she had seen done to him and about the man who had done it, wondering how best to use the knowledge to her advantage.

Herdmanston

Two hours later …

They came up, fox wary and stepping in crouched, swinging half-circles, arrows nocked on smarted bows, heedless of the rain and what that would do to strings.

Addaf knew the Scotch would be gone and his lungs burned from the long run, a frantic hare-leap of panic amid the scattering of their own horses. Now, on foot, they padded back like slinking hounds, for Addaf had lost forty-five men, all the horses and a deal of dignity, which trailed in shreds behind him with the mutters of his men.

They had recovered four horses so far and found all their missing men, though it did them little good: most were dead and at least nine had their right hand or more missing and had died of the blood loss or the horror of it happening. Taken alive, everyone saw, and badly handled.

Five were alive, but none of them would see day’s end. They had used their one good hand and teeth and any thonging or laces they could find to tie off the raw stumps so that the blood did not pump out of them. But they had lost too much and Addaf ordered the bindings cut, to let them slip into the mercy of a long sleep as they lay in sluggish red tarns.

He was aware of Y Crach as a feverish heat at one side of him, but the man – wisely for once – kept silent round him; yet, when Addaf looked, he was head to head with others, who were nodding and scowling.

Addaf had not time for it. He knelt at Hywel’s side, seeing the grey face and the blued lips, the slantwise horror of his severed forearm.

‘No time, the man said,’ Hywel echoed in a soft, twisted wheeze, ‘for niceties. Like taking off our thumbs. The other one, the one called Dog Boy, said his leader would be hard. Hates archers above all his enemies, he said. Hates Welsh more than he hates English, for the Welsh should know better than to serve English Edward.’

Hywel gripped Addaf’s arm hard with the last bloody-fingered hand he had, so that the cloth bunched between his knuckles.

‘Dog Boy, he said he was. Said if any of us lived we should tell the others, all the Welsh, that they are on the wrong side.’

‘The right side is the one that wins,’ Addaf replied, looking into the misting eyes.

‘The other one lashed our right hands with ropes, had a man hold us and another haul our arms out. Then he went down the line of us with his axe. Like he was coppicing …’

‘Who? Who did this? This Dog Boy?’

Hywel was more out than in this world, Addaf realized, but his eyelids flickered and his voice was a last breath.

‘Douglas,’ he said, so slight that Addaf had to put his ear to the lips. ‘The Black himself.’

Then, suddenly, in a clear, strong voice with laughing in it, he said: ‘We will make them dance, we will make them kick …’

Addaf closed the eyes.

‘Bedd a wna bawb yn gydradd,’ he said grimly. The grave makes everyone equal.

ISABEL

O God, whose charity is more painful than Your harshness. In all the years since his father’s death in Greyfriars, the new lord of Badenoch has never visited, simply paid Malise his stipend for guarding me – as his Comyn father did before – on behalf of his kin, my long-dead husband. Yet, Lord, You brought Badenoch to the Hog Tower this year, accompanied by a simpering Malise, anxious for his quarterlies to be continued. A little mirror of his murdered father, this new Badenoch, freckled, red-haired and bantam. He looked round at my straw-strewn stone niche, the window that is a door and the cage beyond it. Then he looked me up and down and slowly wondered at my state and age, not having realized it before. Not quite the Hoor o’ Babylon, wee Johnnie, I told him and watched how prettily he pinked. He ordered my whim for pots and paints and women’s essentials ‘in remembrance of the man who spared me’ – but confirmed Malise in the constant caring of me. The man who spared wee Badenoch was Hal, on that day in Greyfriars when this frowning little lord was a lad, brought to say last farewells to his murdered da to find the killers returned to make sure of it. Kirkpatrick would have done for him, save for my Hal; Malise fled and young Badenoch clearly remembered it, for his look flushed Bellejambe to the roots of his pewter hair. Later, Malise took his revenge with me and, as always, lost more than he gave. I suffered his grunting, futile foulness and learned that Badenoch did not come only to see me, but to put Berwick in order; the English are coming in midsummer, to put an end to Bruce. You may dream of it, I told Malise, and, for once, he had no strength left to punish me. So a victory for endurance – let us hope, O Lord, that this is not a beguilement of empty hope for the Kingdom.

CHAPTER FIVE

Westminster

Feast of St George, April 1314

The Pope was dead and the shiver of it added to the cold ache in the bones. Drip and ache, that was Easter, thought Edward, every miserable cunny-rotted day of it, when the damp crept up your back and no amount of stoked fire could keep the wind from looping in and up your bowels until you coughed and shat hedgepigs.

Like Father. He threw that thought from him, as he always did when it crept in like a mangy dog seeking shelter. Shitting his life down his leg; for all his strength and longevity brought low by a foul humour up the arse, king or no.

Death did not care for rank. The Pope had found that, just as Jacques de Molay had promised from his pyre. Edward, even as the delicious chill of it goosed his flesh, could not help the hug of glee that he was not his father-in-law, the King of France, who had also been cursed in the same breath.

Still, there was room enough for Edward to wonder if his own treatment of the Order of Poor Knights had inherited a waft of that smoke-black shriek from de Molay. He had been light on the Templars, but followed the Pope’s edict and handed their forfeited holdings – well, most of them – to the Hospitallers. Much good may it do them, he thought, though it does me very little for I cannot see the Order of St John coming to my army. The Templars made that mistake by joining my father’s army and the lesson in it is plain enough for a blind man to see.

He wished someone would come to his army, all the same.

‘Who has not responded?’ he demanded and de Valence made a show of consulting the roll, squinting at it in the bright glow of wax candle which haloed the small group in the dim room. No one was fooled; everyone there, the King included, knew he could recite it from memory.

Lancaster, Arundel, Warwick, Oxford, Surrey: the greatest earls of his realm. Plus Sir Henry Percy, bastion of the north.

‘We issued summons to all earls and some eighty magnates of the realm to prepare for war with the Scots,’ de Valence pointed out, as if to say that these six were nothing at all. Edward shifted in his seat, scowling and aching.

Summons to eighty magnates and every earl – even his 13-year-old half-brother, Thomas, Earl of Norfolk – not to mention Ulster and personal, royal-sealed letters to twenty-five rag-arsed Irish chieftains. But the realm’s five most powerful and the north’s shining star, Percy, had all refused and the gall of it scourged him almost out of his seat.

‘When we defeat Bruce, my liege, all matters will be resolved,’ de Valence went on, hastily, as if he sensed the withering hope of the King. ‘We will have twenty thousand men, including three thousand Welsh, at Berwick by this time next month, even without these foresworn lords.’

With smiths and carpenters, miners and ingéniateurs, ships to transport five siege engines and the means to construct an entire windmill sufficient to grind corn for the army. Plus horses – a great mass of horses.

Edward thought sourly of the man who had just left, elegantly dressed, with a plump face that had yet to settle into anything resembling features. But Antonio di Pessagno, the Genoese mercantiler who was as seeming bland as a fresh-laid egg, held the realm of England in his fat, ringed hand, for it was his negotiated loans which were paying for the Invasion.

Edward did not like Pessagno, but the Ordainers – Lancaster, Warwick and the other barons who tried to force him into their way – had banished his old favourites, the Frescobaldi, so he had no choice but to turn to the Genoese. The same earls who ignored him now, Edward brooded, feeling the long, slow burn of anger at that. The same who had contrived in the death of my Gaveston …

‘They claim’, he rasped suddenly, ‘what reasons for refusing my summons to defend the realm?’

‘That they did not sanction the campaign.’

The answer was a smooth knife-edge that cut de Valence off before he could speak. Hugh Despenser, Earl of Winchester, leaned a little into the honeyed light.

‘They say you are in breach of the Ordinances,’ he added with a feral smile.

No one spoke, or had to. They all knew the King had deliberately manipulated the affair so that he breached the imposed Ordinances by declaring a campaign against the Scots without the approval of the opposing barons. Honour dictated they should defend the realm, no matter what – but if they agreed, then they supported the King’s right to make war on his own, undermining everything they had worked for. Their refusal, however, implied that they were prepared to let the Scots mauraud unchecked over the realm and that did no good to their Ordinance cause.

They were damned if they did and condemned if they didn’t, so the King won either way, though he would have preferred to have them give in and send their levies. Still, it was a win all the same and, since Despenser had suggested the idea, he basked in the approval of the tall, droop-eyed Edward while the likes of de Valence and others could only scowl at the favour.

Yet Edward was no fool; Despenser was not a war leader and de Valence, Earl of Pembroke, most assuredly was. Better yet, the Earl hated Lancaster for having seized Gaveston from his custody and executing him out of hand and Edward trusted the loyalty of revenge.

Edward leaned back, well satisfied. All he had to do was march north, to where this upstart Bruce had finally bound himself to a siege at Stirling and could not refuse battle without losing face with his own barons.

‘Bring the usurper to battle, defeat him and we win all – roll the main, nobiles. Roll the main.’

Roll the main, de Valence thought as the approving murmurs wavered the candle flame in a soft patting like mouse paws massaging the royal ego. But the other side of that dice game was to throw out and lose.

That is why they call it Hazard, he thought.

Crunia, Kingdom of Castile

Feast of St James the Less, May 1314

The port was white and pink and grey, hugged by brown land studded with dusty green pines and cypress – and everywhere the sea, deep green and leaden grey, scarred with thin white crests and forested with swaying masts. Light flitted over it like a bird.

Crunia was the port of pilgrims, those who had wearily travelled from Canterbury down through France and English Gascony into Aragon and Castile and could not face the journey back the same way. The rich, or fortunate beggars, would take ship back to Gascony, or even all the way to England – the same ships which brought the lazy or infirm to walk the last little way to the shrine at Compostella and still claim a shell badge.

Hal stared with bewilderment at them, the halt and twisted, the fat and self-important, shrill beldames and sailors, those who thought they could fool God and those footsore and shining with the fervour of true penitents. He had never seen a foreign land and it made his head swim with a strange fear that Kirkpatrick noted with his sardonic twist of smile.

‘Can suck the air from you, can it not,’ he said gently and laid a steady hand on the tremble of one shoulder. Hal looked at him, remembering what he had learned of Kirkpatrick’s past in the land of Oc, fighting Cathars in a holy crusade. Oc was not so far from here, he thought, though he had trouble with the map of it in his head – trouble, too, with the realization that Kirkpatrick was the closest to a friend he had left other than Sim, who came rolling up the quayside as if summoned.

‘No’ very holy,’ Sim growled, staring at the huddled houses before kneeling and laying a hand flat on the cobbles. ‘Mark you, any land is fine after yon ship. Bigod, I can hardly walk straight on the dry.’

No one walked straight on the dry, but Hal tried not to turn and gawp as they helped unload the heavy, precious cargo into the carts they had hired, making it seem as anonymous as dust.

Everyone, pilgrim and prostitute, seemed moulded from another clay entirely, while the stalls were a Merlin’s cave of jeweller’s work and carpets, tableware worked in silver, glass and crystal, ironwork made like lace.

There were Moors, too, swarthy and robed, turbanned and flashing with teeth and earrings; Hal would not have been surprised to meet a dog-headed man, or a winged gryphon on a leash.

‘Are we stayin’ the night?’ demanded Sim. ‘I had a fancy to some comfort and a meat pie.’

‘Little comfort in this unholy town,’ Kirkpatrick answered grimly, ‘and you would boak at the content of such a pie, so it is best we shake this place off our shoes. We will be escorted by the Knights of Alcántara, no less, to a safe wee commanderie some way on the road to Villasirga.’

Hal had seen the Knights arrive, a score of finely mounted men sporting a strange, embellished green cross on their white robes – argent, a cross fleury vert, he translated, smiling, as he always did, at the memory of his father who had dinned heraldry into him.

The new Knights were all in maille from head to foot, with little round iron caps and sun-smacked faces that made them almost as dark as the trading Moors, at whom they scowled in an insult that would have had them skewered in Scotland.

‘They frown at everyone,’ Kirkpatrick answered, when Hal pointed this out, ‘save Doña Beatriz.’

It was true enough – the leader of the Knights bowed and fawned on the elegant, cool and sparkling lady, and then was presented to everyone who mattered as ‘el caballero Don Saluador’, followed by a long string of meaningless sounds which Kirkpatrick said was the man’s lineage. Don Saluador looked at everyone as if he had had Sim’s old hose shoved under his nose.

‘But they hate those ones even more than they hate the Moors,’ Kirkpatrick added, nodding towards a group of men shouldering arrogantly through the crowds. Dressed richly, they had faces as blank and haughty as the statues of saints and wore billowing white blazoned with a red cross which looked like a downward pointing dagger.

‘Fitchy,’ Hal said, still dizzy with the sights and smells of it all.

‘Just so,’ Kirkpatrick confirmed. ‘The cross fitchy of the Order of Santiago – the wee saint’s very own warriors. The Order of Alcántara is so new it squeaks and yon knights never let them forget it.’

‘You have it wrangwise,’ Sim answered, wiping the sweat from his face, and Kirkpatrick, scowling, turned to him.

‘There are others they hate even harder,’ Sim went on and nodded to where the black-robed former Templars walked, stiff-legged and ruffed as dogs, refusing to be anonymous or duck under the scorch of stares from all sides. For all that they sported no device, everyone knew them by their very look, though none dared call them out as heretics.

Christ betimes, Hal thought, the world is stuffed with God’s warrior monks, and it seems the only fighting they do is against each other.

By the time the carts were loaded and ready, the sun was brassed and high, the road crowded with pilgrims fresh from Mass and still in the mood to sing psalms along the dusty road, as if their piety increased with the level of noise they made.

The locals knew better and sneered, both at the singing of these lazy penitents and their foreigner stupidity at walking out in the midday heat. They did not sneer at the Knights of Alcántara, Hal noted, who were riding out in the midday heat with four carts and a motley of strange foreigners.

Rossal and the others took their leave of de Grafton, who had volunteered to stay with the Bon Accord, as if only he was capable of defending it; they needed the ship victualled and ready if they were to succeed, so it seemed sensible – but Hal saw Kirkpatrick frowning thoughtfully over it and wondered at that.

Beyond the port, the air was so clear that it seemed you could see every tree on the foothills that led to the dust-blue horizon etched against the gilding sky. The pilgrims rapidly ran out of enthusiasm for psalms and the column began to shed them like old skin, each one tottering into some panting shade and groaning.

‘Fine idea,’ Sim declared, mopping his streaming face. ‘If I was not perched on a cart, I would be seeking that same shade.’

‘You would not,’ Kirkpatrick answered grimly and jerked his chin to one side, where distant figures squatted, patient as stones.

‘Trailbaston and cut-throats,’ he said with a lopsided grin. ‘Waiting for dark and the passing of the fighting men to come down and snap up the tired and weary, like owls on mice.’

‘Christ betimes, they are robbing pilgrims,’ Sim said, outraged.

‘So they are – almost. The wee saint’s warriors are busy protecting the proper pilgrim route, the Way of St James. Since there are two roads to Santiago, it takes them all their time – though the northern route is used less these days, now that the Moors have been expelled from the road from Aragon to Castile.’

‘This is what happens when you try and cheat God,’ Hal added with a grin.

He had lost the humour in it by the time the day died in a blood and gold splendour, wiped from his lips by too much heat and dust, the ten different languages that made the psalms a babble, the quarrels that broke out on every halt, the stink that hung with them in the dust.

Hal was sharply aware that this was but a lick of what Crusaders had experienced here and that it was worse by far further south and east, in the Holy Land itself; his estimation of his father went up when he thought of him enduring this in the name of God. By the time they turned off the road and into a tree-shaded avenue, Hal was heartily sick of the Kingdom of Castile and the commanderie of St Felix was a blessed limewashed relief.

Stiff-legged, he climbed off the palfrey he had been given and had it removed by a silent figure, blank and shadowed as the dark which closed on them. Led by flickering torches, Hal and the others were escorted into a large room with a stout door to the right and a curtained archway to the left; there were tables and benches, fresh herbs and straw.

‘It is not much,’ said a smooth voice, the French accented heavily, ‘but it is what we use as bed and board.’

They turned to see a tall man with the Alcántara cross on a white camilis that accentuated the dark of his face and the neatly trimmed black beard; his smile was as dazzling as his robe and Doña Beatriz hung off his arm with a familiarity intended to raise the hackles of the black-robed Templars, even if it was only his sister.

‘I am Don Guillermo,’ he announced, raking them with his grin. ‘I assure you, this is really how we live – you see, we can be as austere as Benedictines. Up to a point.’

Rossal, unsmiling, bowed from the neck; the others followed and Hal saw the scowl scarring the face of the German.

‘Our thanks for your hospitality and escort. I will see to my charge before prayers.’

‘Of course,’ Guillermo answered smoothly. ‘Be assured, our best men guard those carts.’

‘I have no doubt of it,’ Rossal answered. He turned to look briefly at Kirkpatrick and then went out, trailed by de Villers. Sim stretched noisily and farted.

‘Not a bad lodging, mark you,’ he declared, glancing at the wall whose bare, rough whiteness was broken by a trellis of poles supporting a short walkway reached by an arched doorway. It was the height of two tall men from the floor.

‘A gallery for minstrels,’ he said and grinned. ‘Some entertainment later, eh, lads?’

In a commanderie of a religious Order? Hal looked at Kirkpatrick, who held the gaze for a moment, and then moved to the nearest door, which was beneath the gallery. It was clearly locked. The curtained archway on the other side of the room led to some steps and Kirkpatrick was sure they reached up to a belltower he had seen on the way in.

‘As neat a prison as any you will see,’ he offered to the returned Rossal, who nodded grimly, and then turned to the door he had been escorted through; the rattle of the locking bar was clear to everyone and he frowned.

‘Where is Brother Widikind?’

The Lothians

At the same time

They roared through the March, looting and burning and with no care now that they had rid themselves of the Welsh. Using fire, using blade, using lies and deceit, they harried the wee rickle of fields and cruck houses in Byres, Heriot, Ratho and Ladyset. They felled ramparts and broke wooden walls, ravaged the Pinkney stronghold at Ballencrieff and showed their faces to the frightened burghers of Haddington.

Fell and bloody were the riders of Black James Douglas, who gorged on fire and sword and pain and never seemed to have enough of it to drive out the hatred he felt for all that had been taken from him.

Then they came down on the weekly market at Seton, because that lord was firmly in the English camp and Black Jamie wanted him scorched for it. They rampaged through the screamers, scattering them with half-mocking snarls and a waved blade. There was little of fodder anywhere, Dog Boy noted, and Jamie nodded, pointing to the church.

‘You can rely on God to make sure of his tithe,’ he said, and bellowed at the others to be quick and to take only the peas and barley, the live chooks and the dead coneys.

They were good, too, careful when loading the stolen eggs and ignoring trinkets – well, in the main. Everyone took a little something, as a keepsake or a token for a woman somewhere, while a bolt of new cloth was blanket and cloak both on a bad night.

Jamie and Dog Boy rode up to the stout-walled tithe barn and Dog Boy skipped off the garron and kicked open the double doors; it was an echoing hall, bare even of mice, and Jamie’s eyebrows went up at that. At the nearby church, the door of it clearly barred from the inside, the priest stood outside, defiant chin raised.

‘The silver is buried,’ he said bitterly, ‘and you are ower late to this feast – others have beaten you.’

Jamie, leaning forward on the pommel, calm as you please, offered the man a smile and a lisping greeting in good Latin.

‘Father Peter,’ the priest replied, clearly unable to speak the tongue, which Dog Boy knew was common enough among parish priests, who understood only the rote of services and would not know Barabbas from Barnabas.

‘Your wealth is safe enough – silver-gilt chalice, is it?’ Jamie replied easily. ‘A pyx, of course – silver or ivory? A silver-gilt chrismatory, a thurible, three cruets and an osculatorium.’

Dog Boy turned to stare in wonder at Jamie, but the priest was unimpressed.

‘One cruet, for we are not rich here. And a pewter ciborium, which you forgot – but since this is the minimum furnishing for a house of God, as any learned man knows, I do not consider you to have the power of Seeing.’

‘God forbid,’ Dog Boy offered and everyone crossed themselves.

‘These others who came’, Jamie went on lightly, ‘were equally restrained, it appears, and only took fodder – unless you have also hidden the contents of your tithe barn.’