Полная версия

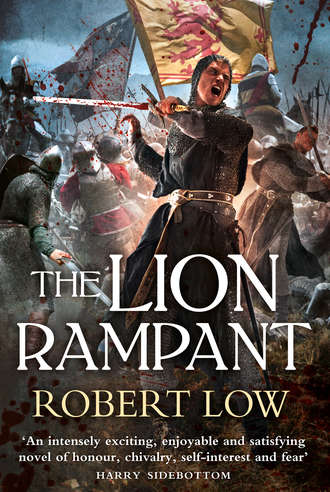

The Lion Rampant

‘Aaahh!’

Sim spun, blocking the snake-like blow with a frantic movement, though the stun of it almost lifted the sword out of his hand. The man who had rushed at him, yelling, was elderly, with a white beard and rheumy eyes; he jumped back and waved his weapon threateningly.

A fire iron, Sim saw. He is attacking me with a fire iron. A retired soldier, said the thought flickering through his mind as he chopped hard at the man’s knee. The man dodged; Sim felt his foot skid on a soggy trencher and then was on his arse, legs and arms flailing.

The old man screamed, wet-mouthed, and raised the fire iron high – but the point of a sword erupted out and upwards from his chest so hard and fierce that it went on into the underside of his jaw. He wailed, high and thin, falling away to reveal the grinning face of Jamie Douglas, staggering as the man’s weight dragged the sword down; he struggled to work his blade free.

‘Christ betimes, that was almost too good to waste: a brace of auld yins at it like Rolands. You will have little better entertainment at this feast.’

Sim’s mask of disgust was ignored and, grinning broadly, Jamie hauled him to his feet, put his boot against the old man’s dead neck, using the leverage to drag his sword free; the blood crept sluggishly out in a viscous tarn, lapping at the apples and plums, the buttered capons, the Shrove griddle cakes and bread spilled from the tables.

Another bloody larder for the Black, Sim thought bitterly as he heard more shouting and turned to it, aware of his weariness. He saw Dog Boy and raised his bloody blade in salute.

Dog Boy had been charged with the woman and her bairn, though he did not know why the Black set such store by it. For all that, he kept her close and grinned as friendly as he could every time he caught her eye; it did not seem to help the tremble in her.

He lost the grin in the hall, with everyone running and shouting and clashing steel. He saw a party break away and head for the stairs and a measure of safety. He saw Sim and Jamie cut down a brace of fighters and thought it was all over until a last knot of men ran at him, wailing desperately. They were led by a big man with a bald head like a flesh fencepost, so that the knob of his original chin alone showed where there had once been a neck. He had a meat cleaver and a deal of trapped-rat courage.

Dog Boy thrust the woman behind him and leaped at this fat giant, hacking overhand with his sword to make the man block with his cleaver, the dirk curving round in his other hand and sinking into the fat man’s belly. He thought he heard a scream from behind him and fought the urge to look and see if the woman and her bairn were under attack.

The fat man reeled away, clutching his belly and looking alternately at Dog Boy and the blood on his palm, a bemused disbelief in his whipped-dog eyes. Another man surged in, Dog Boy struck out and had the blow parried with a small shield – it was only later that Dog Boy saw it was a pot lid – the man grunting as it took the blow. Then he stabbed out with a vicious carving knife.

They are servants, Dog Boy realized suddenly, getting his sword in the way and managing to turn the blow. At his side, Patrick slapped down the knife, smashed his studded leather shoulder into the man’s pot-lid shield and sent him staggering back; a bench caught him just behind the knee and he went over with a despairing cry.

Patrick, snarling like a mad hound, lunged after him, his elbow flailing like a fiddler at a dance, the longsword rising and falling, spraying gleet and blood.

Dog Boy turned and saw the woman, clutching her wailing brat to her and staring, open-mouthed with horror. Aye weel, he thought, hearing the wet, ugly sounds of Patrick making sure his opponent was truly dead, such sights would give you pause.

‘Dinna fash,’ he panted, leaning on his sword, knowing the worst of the matter was done with. ‘The Black ordered you safe and safe you shall be.’

Patrick appeared, his bluff face speckled with blood, and offered her a grin of his own as he cleaned gore and bits of brain from his blade with the hat of the man he had killed.

‘Hot work,’ he offered, but the woman merely buried her face in her swaddled bairn and wept, so he shrugged.

‘Ach – weemin,’ he said. ‘Have you told the quine she is safe?’

‘I have,’ Dog Boy answered firmly, but frowned and added loudly: ‘So it is a puzzle why she is weepin’ so.’

The woman surfaced, tear-tracks streaking through the grime of her face and pointed a shaking hand at the quivering giant, who had dropped his meat cleaver, sunk like a stricken ox and bled to death through the fingers clutching desperately at the hole Dog Boy had put in his belly.

‘That was my da.’

Hal marvelled on that vision of the two Jamies all the rest of that night, strangely detached from the fetid sweat of fear in the chapel, where men crouched like panting beasts listening to the thud and crash on their battened door.

Sir William roared curses back at them and wheedled courage into his own before he collapsed, breathing like a mating bull; one of his men-at-arms mercifully severed the last shreds of his eyestalk and then tried to hand it to Frixco, who shied away in horror.

By morning, it was clear to everyone that Sir William was dying and that Frixco was no leader, so Hal was unsurprised when a man – the same who had physicked the eye off Sir William’s cheek – came and knelt beside him in the stale dim, where the tallow candles gasped. He announced himself as Tam Shaws, a good Scot, and said as much with an air of challenge. Hal said nothing, though he had his own ideas on what made a good Scot.

‘Is he set on red murder, or will the Black spare us?’ Shaws demanded, which was flat-out as a sword on a bench.

Hal shrugged. Truth was, he did not know. He had heard, as had everyone, of Jamie Douglas and his savagery and could only vaguely equate it with the youth he had known. But Dog Boy was with him and, for the life of him, Hal could not see Dog Boy indulging in such tales as were told, with wide-eyed, breathless horror, under every roof in the Kingdom. He said as much and saw the man-at-arm’s eyebrow lift laconically.

‘It is not your life,’ he answered dryly, which was only the truth. Hal rose up, stiff after sitting so long.

‘Is it your wish to surrender provided no harm comes?’ he asked and, after a pause and some exchanged glances – one of them with the whimpering Frixco – Shaws nodded.

‘Unbar the door,’ Hal ordered.

It came as a shock to Jamie Douglas when the clatter of moving furniture heralded something imminent, for he had not thought the defenders had that much courage in them. Still, he thought savagely, better this way – I need this place taken and swiftly.

‘Ready, lads,’ he called out, and the black-cloaked men on the stair behind and trailing into the bloody ruin of the hall, still picking wolfishly at the wreck of the feast, flexed chapped knuckles on their weapons.

Dog Boy, standing guard over the crouched woman – Christ betimes, hardly more than a girl in the pewter dawn light of the hall – saw her tremble and touched her shoulder reassuringly; she had wept most of the night and hugged her bairn to her, so that the episode of killing her da had fretted Dog Boy more than a little and he felt she should know other folk cared yet for her.

‘The Black has placed you under his cloak, yourself and bairn both,’ he reminded her and saw the wan smile.

The door above creaked open and everyone tensed, waiting for the last mad leap of the desperate. Instead, a man stepped through, nondescript in hodden, with a matted tangle of iron hair and beard. Folk squinted, not knowing who he was.

‘Young Jamie,’ the man said quietly. ‘They will surrender if you spare them. It would be sensible to consider it.’

Only Sim knew, as soon as he heard the voice, and looked up.

‘Sir Hal,’ he yelled and Jamie Douglas jerked like a stung beast. Recovering, he grinned and shook his head in awe at this, a hero sprung like a tooth sown by Cadmus – a man, he was forced to admit, whose presence in Roxburgh he had shamefully overlooked.

‘Sir Hal of Herdmanston. Here you were, a prisoner we came to free,’ he called out for the others to hear, for it did no harm to stamp your mark on the moment, ‘and here you are, having taken this wee fortalice of your ain accord.’

ISABEL

The nuns are here, the one called Sister Constance and the other, Alise. What kind of name is Alise for a nun? One for a nun who thinks herself boldinit and more mighty than the Almighty, that’s what kind. Wee Constance is kind enough in her way, though she believes what she is told, of this hoor of Babylon kept in a cage on the walls of Berwick until Hell calls her for a seat at her personal bad fire. The convent they come from is the same one where I was held for ransom by Malenfaunt long years since, but all his charges have been scourged from it – I wonder what became of the little oblate, Clothilde? She and all the rest have been replaced, Constance told me primly, by decent, Christian women. Well – all but Alise, who is a goad in the hands of one of Satan’s lesser imps. From woman sprang original sin, she tells me often, and all evil and all suffering and all impurity – with a sly little smile that tells me she does not include herself as any kin of Eve in it. Who is without sin? Even an Order Knight would need to live in a desert to obey God’s Law in this kingdom. I said as much to her at first and saw the little cat’s-arse purse she made of her lips at having been so spoken to, though she could do nothing then. Afterwards, the number of folk allowed into the bailey to gawp seemed to increase for a time, and had been encouraged to jeer until they were stopped by, of all folk, Malise, who does not like his authority over me challenged, never mind by a mere nun. Sister Alise hates being one of those given the task of sleeping across my door each night on a straw pallet, to make sure nothing ungodly happens and no visitor takes advantage. Not unless it is Malise Bellejambe, of course. What does she know of me, this Alise? What do any of them know, slobbering and laughing below me like I am some babery beast? I am Isabel MacDuff and I am loved. My Hal lives yet – I would know if he did not – and he will come. Miserere nostri. Dies irae, dies illa, solvet saeclum in favilla. Pity us. Dreaded day when the universe will be reduced to ashes.

Amen.

CHAPTER TWO

Edinburgh Castle,

Feast of St Fergna of Iona, March 1314

They came up to the glowering rock and the black fortress on it through a haar-haze hung thick as linen, with Hal sore and tired from unaccustomed riding. They passed a huge cart tipped back and weighted so that the trace pole could support the carcass of a hog; the gory butchers paused to look and wave and call out good-natured greetings to Jamie as he passed.

‘The Good Sir James,’ Sim said, nudging his mount easily alongside Hal so that he could speak soft. ‘Darling of the host, is the Black Lord of Douglas. A derfly, ramstampit man o’ main.’

Hal met Sim’s eye, saw the mock in it and managed a smile. He saw, too, the white of Sim Craw – he had got used to it now, though it had come as a shock, all that snow on his lintel. It had come to him, when the Dog Boy suggested he brighten himself for the arrival of the Earl of Carrick, that he himself was old – each pewter curl that fell from his clipped head, courtesy of the spared girl, Aggie, told of that. And Sim was older by only a handful and a half of years.

Since no one had had much care for the style of a prisoner, wee poor noble or not, Hal had not realized how he’d looked until sat in front of the water-waver of a bad mirror and witnessed this apparition with a greasy tangle of grey hair matting its way into a madness of bushed beard.

Only the eyes, grey-blue and blank, could be seen and when Hal looked in them he was dizzied, for it felt as if there was someone else looking back at him, as if his body had been rented like an abandoned house. When his beard vanished, the gaunt lantern-jawed man who appeared was no more familiar.

Aggie, rocking her bairn in a shawl looped across her back while she clipped, tongue between her teeth, eventually announced that she could do no more. The result, Dog Boy announced critically, was suitable and Hal, seven years removed from the gawky youth who had cared only for dogs, was astonished by this new Dog Boy, a muscled, skilled warrior and the shadow of the Black himself. He was even called Aleysandir now, a fine set-up man with a name and the style and wit to know how a wee lord from Lothian should be seen by an earl. Yet he was still Dog Boy to those who knew him well.

Hal had heard some matters of the outside world in his prison, enough to know that he had missed even more, but the arrival of the Earl of Carrick had confused him. He had been expecting the Bruce, but it was the brother who came and Hal cursed himself for a fool.

Had he not been there when the Earl of Carrick became king? Now brother Edward was Earl of Carrick – and the last of the brothers, too. The memory of the others, dead and gone in the furtherance of Robert Bruce to the throne, had soured the fête of Edward Bruce’s arrival at Roxburgh, a day after Hal’s release.

He and Hal had met once the mummery had been done with: the greetings and fine speeches, the official surrender and promises made. Sir William Fiennes, barely clinging to life, left in a litter with Frixco, uncaring little bachle, trailing after and hugging close to the bier as if the dying brother was a sealed surety for his own safety. Dog Boy saw Aggie hawk and spit pointedly and scornfully as he went; she was clearly bright with the wonderful possibility of being allowed to go where she would and with a sum of money to keep her and the bairn for a time.

Edward had been all delight and grins, his face flushed, fleshy and even broader than it had been, though there were harsh lines at the corner of eye and mouth which spoke of the hardships of the seven years since Hal had last seen him.

‘Aye, times have changed and for the better,’ he had growled, handing the fresh-shorn Hal a horn cup of wine. ‘The King wants Edinburgh, Stirling and Roxburgh in his grip by summer. It is an ambitious swoop – but, by God, the Black has opened the account well.’

‘As well he chose this yin first,’ Hal had answered, ‘else I would be in prison still.’

‘Isn’t it, though?’

Edward had walked to the tent entrance and stood for a moment, shaking a sad head.

‘A pity,’ he had said in French. ‘It is a pretty place, Roxburgh, and shame on us for having to tear it down.’

Hal knew why: they could not garrison it sufficiently to keep the English out if they came back and Roxburgh, like Edinburgh and Stirling, was a bastion for the English in the Kingdom, a fount of supply and centre of domination. Still, there were others.

‘Even if they all fall, the English will still have Berwick and Bothwell,’ he’d said and Edward nodded.

‘Aye, and Dunbar, but none are as brawlie as the great fortalices of Stirling, Edinburgh and here. Besides, taking them throws most of the last garrisons of English out of the Kingdom and sends a sign to English Edward’s enemies that, once again, he is the weak son. Not a Longshanks, for all his length of leg.’

He’d paused, swilled wine in the goblet, frowning at it as if some clegg had flown in.

‘I know why you speak of Berwick,’ he’d said suddenly and Hal jerked with the gaff of his words. They stared at each other for a moment.

‘She is there still?’

The question hunched itself like a crookback beggar with a hand out and was not answered for a long time. Then, however, Edward had shifted slightly.

‘Isabel MacDuff is there still. In a cage hung from the inside wall. The King ordered us to try Berwick’s castle two years since. Got one of Sim of Leadhouse’s fancy ladders up and disturbed a dog on the same battlement. It set up a din of howling and barking, so that the guard came to kick its arse and found us.’

He’d stopped, shaking his head at the memory of the mad scrambling retreat.

‘You left her because of a wee dug,’ Hal had said and it was not a question; it had enough bleak censure in it for Edward’s eyes to blaze and his head to snap up.

‘My sister Mary was in a similar cage – Christ’s Bones, if ye had looked up at any time ye would have seen her hanging on Roxburgh’s battlements. My other sister Christina is held in a convent. My niece is held in yet another and the Queen’s whereabouts is not even known. D’ye think we do not care, Lord Henry?’

Hal saw he had gone too far and with no justice in it, so he’d nodded grudgingly.

‘For the first year they kept me close and mainly in the dark,’ he’d told Edward blankly, and for all the light his tone made of it his eyes were as smoked as the locked dim he’d had to endure for so long.

‘They hourly expected word from English Edward,’ Hal had gone on, hearing his voice as if it belonged to someone else, conscious of his pathetic attempt to be wry and matter-of-fact, ‘but he was busy dying, so it never came and the son became too busy with his catamite and his annoyed barons. In the end, they brought me out and treated me better – but Princess Mary was gone by that time.’

Mollified, Edward Bruce had subsided a little, finishing his wine and pouring more.

‘Aye. Beyond our reach – so you know the taking of Roxburgh was not on her account,’ he had growled.

Nor on mine, Hal had thought grimly to himself, for all Jamie Douglas gave out that it was. When he’d said it aloud, Edward had agreed with a curt nod.

‘So also with Berwick,’ Edward had added pointedly, ‘which will be taken in the end and the doing of it will be less about Isabel MacDuff and more to deny it to the English.’

He’d then thrown himself into a curule chair, draping one leg over the arm.

‘Yet we care about our womenfolk, Lord Hal. I would not be so free and easy with the King as regards these matters. He is not the man you knew, being fresh to the kingship then.’

He’d stared moodily, glassily, into the wine and had spoken almost to himself.

‘Now he is fixed on securing matters, on ensuring that everyone kens he is king. Nothing else matters but that and you step soft round him these days.’

‘I have read the Declaration of the Clergy,’ Hal had told him and had back a surprised look.

‘Have you indeed? They were solicitous of your welfare in the end, to fit you with a copy of that in your cell. Shame we had to poke out Sir William’s best eye, then, for it seems he did not deserve it – what did you think of that document?’

Hal remembered what that question had raised in him. Aggie, the girl who had served him meals, had brought it and she had plucked it from the kirk door, one of the many expensive and laboriously made copies nailed there. She had wanted to know what was in it but could not read, nor dared take it to anyone in Roxburgh who might.

What was in it? At first, the joyous honey of a candle, the first Hal had seen up close in an age and even the blur of tears it brought to his squinting eyes was a joy. The second was the smell: the musk of the parchment, the sharpness of the oak-gall ink – the breath of Outside. That, in the end, was worth more than the Declaration of the Clergy itself, a pompous piece of huff and puff to make Robert Bruce seem the very figure of a king and his sitting on the throne far removed from any hint of murderous usurping.

‘Smoke and shiny watter,’ Hal had told Edward eventually. ‘Bigod, though, they almost convinced me that the Bruce is descended from Aeneas o’ Troy himself. A Joshua and white as new milk on a lamb’s lip.’

Edward had laughed then, sharp and harsh, spilling wine on his knuckles and sucking it off. It came to Hal that the Earl of Carrick was mightily drunk and that it was no strange thing for him.

‘Ah, Christ’s Wounds, we have missed you, Lord Hal – but it is as well you were safe locked up, for plain speaking is not the mood of now, certes. I would not share your view of the bishops’ fine work with my brother. If you even get to see him.’

He’d paused moodily.

‘I mind you were close to him, mark you. You and Kirkpatrick. Like a brace of clever wee dugs working sheep for their master.’

There was old envy and bitterness there, which Hal had decided was best to ignore.

‘How is Kirkpatrick?’ he’d asked, suddenly ashamed that he had not thought of the man since he had been released.

‘Auld,’ Edward had replied shortly. ‘You may not see the King at all,’ he then said. ‘And if you do, it will not be a straight march in to where the Great Man sits, taking your ease in the next seat. Naw, naw. There are steps, neat as a jig: walk forward and stop. Kneel. Never look at him. Never speak to him unless invited.’

This kingdom is not large enough for the pair, Hal had thought, hearing the savage bile in his voice. Then Edward had recovered himself and smiled, drained the goblet and risen.

‘Well, good journey to you. I am away to kick the stones out of Roxburgh. Pity – it is a pretty place.’

Prettier than here, Hal thought now, looking up at the rotting-tooth rock of Edinburgh Castle, while they wound a way through the siege lines.

They passed tents, a black Benedictine who was crouched like a dog to hear confessions, a sway-hipped gaud of shrill, laughing women who stared brazen invites at the newly arrived heroes of Roxburgh. Somewhere behind them a pair coupled noisily while the camp dogs circled, looking to steal anything vaguely edible.

Hal felt the heat of forges, tasted the sweat and stale stink of a thousand unwashed, the savour of cook and smith fire as they picked their way through the tangle and snarl of a siege camp. He was fretted and ruffled by the place even as it seemed to him that he moved in a dream, too slowly and somehow detached from it all.

Too much, too quick after seven years of being a prison hermit, he thought, yet the sights and sounds flared his nostrils with old memories.

The world passed him like a tapestry in a long room: a ragged priest singing psalms; squires rolling a barrel of sand through the mud to flay the maille in it of rust; a hodden-clad haughty with his lord’s hawk on one wrist; two men, armoured head to toe but without barrel-helms, running light sticks at each other in practice tourney, pausing to raise greeting hands to Jamie. Only their eyes could be seen in the face-veiled coifs of maille.

Out beyond them, close under the great rock and walls, was a line of hurdles, pavise protection for the crossbows and archers. Beyond that, close under the looming hunch of Edinburgh’s rock, a cloak of murderous crows picked mournfully through the faint stench of rot and the festering corpses of men who were too far under the enemy bows to be recovered for decent burial.

Men moved in blocks, drilling under the bawls of vintenars; Hal saw that some had only long sticks, as if the spearheads had been removed from their shafts, and that too many were unarmoured, with not even as much as an iron hat.

‘Thrust – thrust. Push.’

The sweating men clustered in a block, hardly knowing right from left, half of them unable to speak the other half’s tongue and none of them having met before; they staggered and stumbled and cursed.

The ones who had done this before, the better-armed burghers and armoured nobiles of the realm, moved smoothly through the drills, but they did not laugh at the rabble; they would all depend on each other when push came to thrust.

Hal moved through this misty, half-remembered world of noise and stink and death, made more grotesque by the shattering bright of banners and tents and surcotes dotting it like blooms.

Brightest of all was the Earl of Moray’s flag, big as a bedsheet, fluttering in the dank breeze. It did not show the arms Hal remembered, but the old lessons dinned into him by his father surfaced like leaping salmon: or, three cushions within a double tressure flory counterflory gules. It was the arms of Randolph, right enough, but new-wrapped in the red and gold royal trappings of Scotland.