Полная версия

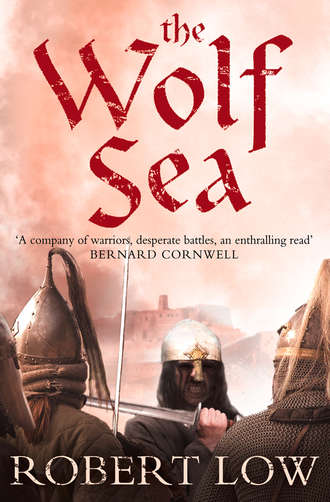

The Wolf Sea

Wound fever, I thought, seeing how bad his limp was – Einar had given him a sore mark, right enough, that day on a hill in the Finns’ land. The Norns’ weave is a strange pattern: Einar was now dead and Starkad was standing there in a red tunic, blue wool breeks, a fine, fur-lined cloak fastened with an expensive pin and a silver jarl torc round his neck. He was, it seemed, making sure I knew his worth.

‘So, Orm Ruriksson,’ he said. There was a shifting round me, the little sucking-kiss sound of eating knives coming out of sheaths. I placed my hands flat on the table. He had two others at his back – one with squint eyes – but I knew there would be more outside, ready to rush to his aid.

‘Starkad Ragnarsson,’ I acknowledged – then froze, for he was wearing a sword at his side and he and his men had dared swagger through Miklagard with weapons openly, which fact had to be considered.

Not just any sword. My sword. The rune-serpent blade he had stolen.

He saw that I had spotted it. He had a smile like the curve of that blade and, behind me, I felt the heat and the stir and heard the low rumble of a growl. Finn.

‘I have heard of the death of Einar,’ Starkad said, making no effort to come closer. ‘A pity, for I owed him a blow.’

‘Consider it Odin luck, since he would have balanced you up with a stroke to the other leg if you had met again,’ I replied evenly, the blood thundering in my ears, ringing out the question of how he came to be wearing that sword. Had he stolen it from Choniates, too? Had the Greek given it to him – if so, why?

Starkad flushed. ‘You yap well for a small pup. But you are running with bigger hounds now.’

‘Just so,’ I answered. This was easy work, for Starkad was not the sharpest adze in the shipyard for wordplay. ‘Since we are speaking of dogs – have you been back to sniff Bluetooth’s arse? Does that King know that you have lost both the fine ships he gave you? No, I didn’t think so. I am thinking he may not stroke your belly, no matter how well you roll on your back at his feet.’

The flush deepened and he laid one hand casually on the hilt of the sabre by way of reply. He saw me stiffen and thought it recognition of the blade and smiled again, recovering. In truth, it was the sight of his pale fingers, like the legs of a spider, sliding along the marks I had made on the hilt, watching them unconsciously trace the scratches, all unknowing.

‘Look…’ began the tavern-owner, his hands trembling as he wiped them over and over on his apron. ‘I want no trouble here…’

‘Then fasten yer hole shut,’ growled the squint-eyed man, his affliction adding to the savagery of his tongue. The tavern-owner winced and backed off. I saw little Drozd sidle away from us, as though we had plague.

‘King Harald can spare two such ships,’ Starkad went on dismissively. ‘I have been tasked with something and will travel to the edge of the world to obey my King.’

I mock-sighed and waved an airy jarl hand at a seat, as if in invitation to discuss this matter that troubled him. I hoped to get him closer, away from the door and the men at his back and the ones I was sure were outside. There would be a fight and blood, since they had weapons and we did not and that would bring the authority of the Great City down on us, but still…

He was polished as a marble step and no fool. ‘You are not what I seek, boy,’ he said with a sneer that refused my invitation. ‘Nor any of these who treat you like a ring-giver on a gifthrone, for all that you have neither seat, nor neck ring, nor even ship to mark you. No sword, either, since I took it.’

He drew back a little from his hate then and forced a smile into my face, which I knew was pale and stricken. I felt the Oathsworn behind me, trembling like ale at an over-full brim and Finn, quivering, barely leashed, finally snapped his bonds.

A bench went over with a clatter and he howled himself forward at Starkad, who whipped that sabre out with a hiss of sound, fast as the flick of an adder’s tongue. Finn, with nothing but his fists, came up two foot short of Starkad’s face, with the point of the rune-serpent sword at his neck. Someone squealed; Elli, I thought dully.

I held up my hand and leashed the others, which act gave me a measure of stone-smoothness, for Starkad noted that and was impressed, despite himself. I could hardly breathe; I wondered if he knew how deadly that blade against Finn’s neck truly was. Even just resting it left a thin, red line. For his part, Finn had froth at the edges of his mouth and I knew that one more comment and he would run his neck up the blade, just to get his hands round Starkad’s own.

‘I have heard tales of this blade,’ Starkad said softly. ‘It cut an anvil, I hear.’

‘Just so,’ I agreed, dry-mouthed. ‘Perhaps, Finn, you should come and sit by me. Your head is hard, but not harder than the anvil that blade was forged on.’

The rigid line of Finn softened a little and he took a step backward, away from the blade. Each step laboured, he unreeled from the hook of that runesword. I breathed. Starkad, smirking, waited until Finn was seated, then sheathed the weapon; life flooded back to the room with a breathy sigh.

‘You have the look of a jarl,’ I said into Starkad’s smirk, my chest still tight with the fear of what might just have happened, ‘but you should beware the jarl’s torc.’

‘You should only beware it when you do not have it,’ Starkad spat back. ‘The mark of ringmoney is the mark of a gift-giver, whom men follow.’

I said nothing to that, for Gunnar Raudi – my true father – had often told me that you should never interrupt an enemy who was making a mistake. I already knew the secret of the jarl torc Starkad was so proud of wearing. It was just a neck ring of silver, which we still call ringmoney, whose dragonhead ends snarl at one another on your chest.

The secret was that the real one was made of steel, carried by the men who wielded it for you. It hung round your neck, another kind of rune serpent, at once an ornament of greatness and a cursed weight that could drag you to your knees and which you could not take off in life.

I knew that from Einar, who had warned me of it as he died by my hand, sitting on Attila’s throne. Now I felt the weight of it myself – even though I could not, as Starkad had seen, afford a real one.

‘I seek the priest, one Martin, the monk from Hammaburg,’ Starkad went on. ‘You know where he is, I am thinking.’

I was silent, knowing exactly what it was Starkad sought. Not a silver hoard at all, but Martin’s treasure, the remains of his Christ spear, the one stuck in the side of the White Christ as he hung on the cross and whose iron head had helped make the sabre Starkad now wore. He did not know that and I leached a little comfort from the secret.

Now that King Harald Bluetooth was a Christ-man himself, he fancied this god spear to help make everyone in his kingdom stronger in the Christ faith – no matter that the Basileus of the Romans claimed such a spear already resided in the Great City. Like me, Bluetooth believed Martin had the real one.

‘He fled,’ Starkad added, when my silence stretched too far. ‘The monk fled. To here, I am thinking, and to you, since you are the only ones he knows.’

It was a good thought, for Martin had been with us for long enough, but Starkad did not know that it was not as a friend. My tongue was already forming the words to tell him this when the thought came to me that we could not – dare not – take him here. It was certain that the Watch had already been called and Starkad was measuring his time like a shipmaster tallies his distances, down to the last eyeflick.

Miklagard was a haven for Starkad; he had to be lured out of it.

‘East,’ I said. ‘To Serkland and Jorsalir, his holy city.’

I have my own thoughts on who made me gold-browed at that moment, to come up with a lie and the wit to speak it with such shrugging smoothness. Like all Odin’s gifts it was double-edged.

He blinked at the ease with which I had given up the information and you could see him weigh it like a new coin and wonder if it rang true when you dropped it on a table. I felt the others twitch, though, those who knew it to be a lie, or suspected the same. I hoped Starkad did not look in their bewildered eyes.

In the end, he bit the coin of it and decided it was gold. ‘Let this be an end of things between us, then. Einar is dead and I have no more quarrel with the Oathsworn.’

‘Return the sword you stole and I will consider it,’ I told him. ‘I once thought you a wolf, Starkad, but it turns out you are no more than an alley dog.’

He had the grace to redden at that. ‘I took the sword the same way you took my drakkar – because I could and it was needful,’ he replied, narrow-eyed with hate. ‘It stays with me because you and your Oathsworn pack cost me dear and I will count it bloodprice for the losses.’

‘Not the last losses you will have,’ Kvasir interrupted angrily. ‘We are not finished with you – take care to keep beyond reach of my blade, Starkad Ragnarsson.’

‘What blade?’ sneered Starkad and slapped his side. ‘I have the only true blade you nithings owned.’

The door opened in a blast of wind and rain and a head hissed urgently at Starkad’s back. It did not take much to know the Watch was coming up the street. Starkad leaned forward at the hip a little and his lip curled.

‘I know you, Kvasir, and you, Finn Horsehead. You also, boy Bear Slayer. I will find out the truth of what you say. If you spoke me false here, or if you get in my way, I will make you all unwind your guts round a pole until you die.’

He backed out of the door while I was still blinking at the picture he had placed in my head with that last one, for I had heard of this cruel trick.

There was a surge, like a wave breaking on a skerry, and I hammered the table to bring the Oathsworn up short, while the others in the tavern scrambled to be out and away. Finn hurled one luckless chariot-racing fan sideways, then stopped, sullen as winter haar.

‘We have to kill Starkad,’ he growled, sitting. ‘Slowly.’

‘Is this sword so valuable, then?’ asked Radoslav. ‘And who is this priest?’

I told him.

‘What holy icon?’ demanded Brother John when he heard my brief tale of Martin and his spear.

‘A spear, like Odin’s Gungnir, only a Roman one,’ I answered. ‘The one they stuck in the Christ when he hung on the cross. Only the metal end is missing from it.’

Brother John’s mouth hung open like the hood of a cloak, so I did not mention that the metal end had been used in the making of the runed sabre Starkad had stolen to feed the greed-fire of Architos Choniates. I did not understand why Starkad had the sword, all the same.

‘Another Holy Lance?’ Brother John was a flail of scorn. ‘The Greeks-who-are-Romans here swear they have one, tucked up in a special palace with Christ’s bed linen and sandals.’

I shrugged. Brother John snorted his disgust and added, scornfully, ‘Mundus vult decipi.’

The world wants to be deceived…I wasn’t sure if it was a judgement on Martin’s desires or on just how genuine the spear was. But Brother John was silent after that, deep in thought.

‘Concerning this sword…’ Radoslav began, but the Watch piled in then and the tavern-owner went off into an arm-wave of Greek. There were looks at us, then back again, then at us.

Eventually, the Watch commander, black-bearded and banded in leather, peeled off his dripping helmet, tucked it in the crook of his arm, sighed and came towards us. His men eyed us warily, their iron-tipped staffs ready.

‘Who leads?’ he asked, which let me know he was no stranger to our kind. When I stood up, he blinked a bit, for he had been looking expectantly at Finn, who now showed him a deal of sarcastic teeth.

‘Right,’ said the Watch commander and jerked a thumb back at the tavern-owner. ‘Not your fault, Ziphas says, but he still thinks you brought armed men to his place. Scared off his custom. Neither am I happy with the idea of you lot blood-feuding on my patch. So beat it. Consider it lucky you have no weapons yourselves, else I would have you in the Stinking Dark.’

We knew of that prison and it was as bad as it sounded. Finn growled but the Watch commander was grizzled enough to have seen it all and simply shook his head wearily and wandered off, wiping the rain from his face. Ziphas, the tavern-owner, still smearing his hands on his apron, finally left it alone and spread them, shrugging.

‘Maybe a week, eh?’ he said apologetically. ‘Let folk forget. If they see you here tomorrow, they will not stay – and you don’t spend enough to make up the difference.’

We left, meek as lambs, though Finn was growling about how shaming it was for a good man from the North to be sent packing by a Greek in an apron.

‘We should follow Starkad now,’ Short Eldgrim growled. ‘Take him.’

Finn Horsehead growled his agreement, but Kvasir, as we shrugged and shook the rain off back in our warehouse, pointed out the obvious.

‘I am thinking Starkad’s crew are now hired men and so permitted weapons,’ he observed. ‘Choniates will stand surety for them here like a jarl.’

Radoslav cleared his throat, cautious about adding his weight to what was, after all, not much of his business. ‘You should be aware that this Starkad, if he is Choniates’ hired man, has the right of it under law. We will have warriors from the city on us, too, if blood is shed and not just the Watch with their sticks. Real soldiers.’

‘We?’ I asked and he grinned that bear-trap grin.

‘It is a mark of my clan that when you save a man’s life you are bound to keep helping him,’ he declared. ‘Anyway, I want to see this wonderful sword called Rune Serpent.’

I thought to correct him, then shrugged. It was as good a name for that marked sabre as any – and it was how we got it back that mattered.

‘Which brings up another question,’ said Gizur Gydasson. ‘What was all that cow guff about the monk going to Serkland? Has he really gone there?’

That hung in the air like a waiting hawk.

‘If force will not do it, then cunning must,’ Brother John said before I could answer, and I saw he had worked it out. ‘Magister artis ingeniique largitor venter.’

‘Dofni bacraut,’ Finn growled. ‘What does that mean?’

‘It means, you ignorant sow’s ear, that ingenuity triumphs in the face of adversity.’

Finn grinned. ‘Why didn’t you say that, then?’

‘Because I am a man of learning,’ Brother John gave back amiably. ‘And if you call me a stupid arsehole again – in any language – I will make your head ring.’

Everyone laughed as Finn scowled at the fierce little Christ priest, but no one was much the wiser until I turned to Short Eldgrim and told him to find Starkad and watch him. Then I turned to Radoslav and asked him about his ship. Eyes brightened and shoulders went back, for then they saw it: Starkad would set off after Martin and we would follow, trusting in skill and the gods, as we had done so many times before.

Anything can happen on the whale road.

TWO

After Starkad’s visit to the Dolphin, we moved to Radoslav’s knarr, the Volchok, partly to keep out of the way of the Watch, partly to be ready when Short Eldgrim warned us that Starkad was away.

There was a deal to be done with the Volchok to make it seaworthy. Radoslav was a half-Slav on his mother’s side, but his father was a Gotland trader, which should have given him some wit about handling a trading knarr the length of ten men. Instead, it was snugged up in the Julian harbour with no crew and costing him more than he could afford in berthing fees – until he had heard that a famous band of varjazi were shipless and, as he put it when we handseled the deal, we were wyrded for each other.

But he was no deep-water sailor and every time he made some lofty observation about boats, Sighvat would grin and say: ‘Tell us again how you came to have such a sweet sail as the Volchok and no crew.’

Radoslav, no doubt wishing he had never told the tale in the first place, would then recount how he had fallen foul of his Christ-worshipping crew, by drinking blood-tainted water in the heat of a hard fight and refusing, as a good Perun man, to be suitably cleansed by monks.

‘The Volchok means “little wolf”, or “wolf cub” in the Slav tongue,’ he would add. ‘It is rightly named, for it can bite when needs be. My name, schchuka, means “pike” for I am like that fish and once my teeth are in, you have to cut my head off to get me to let go.’

Then he would sigh and shake his head sorrowfully, adding: ‘But those Christ-loving Greeks loosened my teeth and left me stranded.’

That would set the Oathsworn roaring and slapping their legs, sweetening the back-breaking work of shifting ballast stones to adjust the trim on his little wolf of a boat.

Trim. The knarr depends on it to sail directly, for it is no sleek fjord-slider, easily rowed when the wind drops. Trim is the key to a knarr as any sailing-master of one will tell you. They are as gripped by it as any dwarf is with gold and the secret of trim is held as a magical thing that every sailing-master swears he alone possesses. They paw the round, smooth ballast stones as if they were gems.

Knowing how to sail is easy, but reading hen-scratch Greek is easier than trying to fathom the language of shipmasters and I was glad when Brother John tore me from a scowling Gizur, while we waited for Short Eldgrim.

The little Irisher monk was also the one man I seemed able to talk to about the wyrd-doom of the whole thing, who understood why I almost wished we had no ship. Because a Thor-man had drunk blood and offended Christ-men, I had a gift, almost as if the Thunderer himself had reached down and made it happen. And Thor was Odin’s son.

Brother John nodded, though he had a different idea on it. ‘Strange, the ways of the Lord, right enough,’ he declared thoughtfully, nodding at Radoslav as that man moved back and forth with ballast stones. ‘A man commits a sin and another is granted a miracle by it.’

I smiled at him. I liked the little priest, so I said what was on my mind. ‘You took no oath with us, Brother John. You need not make this journey.’

He cocked his head to one side and grinned. ‘And how would you be after making things work without me?’ he demanded. ‘Am I not known as a traveller, a Jorsalafari? I have pilgrimed in Serkland before and still want to get to the Holy City, to stand where Christ was crucified. You will need my knowledge.’

I was pleased, it has to be said, for he would be useful in more ways, this little Irski-mann and I was almost happy, even if he would not celebrate jul with us, but went off in search of a Christ ceremony, the one they call Mass.

Still – blood in the water. Not the best wyrd to carry on to the whale road chasing a serpent of runes. Nor were the three ravens Sighvat brought on board, with the best of intent – to check for land when none was in sight – and the sight of them perched all over him was unnerving.

We tried to celebrate jul in our own way, but it was a poor echo of ones we had known and, into the middle of it, like a mouse tumbling from rafter into ale horn, came Short Eldgrim, sloping out of the shadows to say that two Greek knarr were quitting the Julian, heading south, filled with Starkad’s war-dogs and the man himself in the biggest and fastest of them.

We hauled Brother John off his worshipping knees, scrambled for ropes and canvas and, as we hauled out of the harbour, I was thinking bitterly that Odin could not have picked a better night for this chase – it was the night he whipped up the Wild Hunt hounds and started out with the restless dead for the remainder of the year.

Yet nothing moved in the dark before dawn and a mist clung to the wharves and warehouses, drifting like smoke on the greasy water, like the remnants of a dream. The city slept in the still of what they called Christ’s Mass Day and no-one saw or heard us as the sail went up and we edged slowly out of the harbour, on to a grey chop of water.

Wolf sea, we called it, where the water was grizzled-grey and fanged with white, awkward, slapping waves that made rowing hard and even the strongest stomachs rebel. Only the desperate put out on such a sea.

But we were Norse and had Gizur, the sailing-master. While there were stars to be seen, he stood by the rail with a length of knotted string in his teeth attached to a small square of walrus ivory and set course by it.

He also had the way of reading water and winds and, when he strode to the bow, chin jutting like a scenting hound, turning his head this way and that to find the wind with wettened cheeks, everyone was eased and cheerful.

Him it was who had spotted the knarr ahead, not long after we had quit the Great City, on a morning when the frost had crackled in our beards. For two days we kept it in sight, just far enough behind to keep it in view. Only one, all the same – and, if we saw it, it could see us.

‘What do think, Orm Ruriksson?’ he asked me. ‘I say she knows we are tracking her wake, but then I am well known for being a man who looks over one shoulder going up a dark alley.’

Then a haar came down and we lost her – or so we thought. Finn was on watch while the rest of us hunkered down to keep warm. The sail was practically on the spar and yet we swirled along, for we were caught in the gout that spilled through the narrow way the Greeks call Hellespont and only us and fish dared run it in the dark. I had resigned myself to casting runes to find Starkad when Finn suddenly bawled out at the top of his voice, bringing us all leaping to our feet.

By the time I reached the side, there was only a grey shape sliding away into the fog. Finn, scowling, rubbed the crackling ice from his beard.

‘It was a knarr, right enough – we nearly ran up the steer-board of it, but when I hailed it, it sheered off and vanished south.’

‘As would I have done,’ Brother John chuckled, ‘if you had hailed me in your heathen tongue. Did you try Greek at all?’

Finn admitted he had not mainly because, as he said loudly and at length, he could not speak more than a few words as Brother John knew well and if he had forgotten he, Finn, would be glad to jog his memory with a good kick up the arse.

‘Next time, try your few words first,’ advised Brother John. ‘“Et tremulo metui pavidum junxere timorem” as the Old Roman skald has it. “And I feared to add dreadful alarm to a trembling man” – bear it in mind.’

Everyone chuckled at a shipload of Greeks being scared off by a single Norse voice, while Finn, spilling ale down his beard and trying to stuff bread in his mouth as he drank, grumbled back at them.

Sighvat pointed out that if Finn did hail another ship as Brother John wished, it would turn round and vanish as well, for who wants to hear someone wanting to know how much it costs to have your balls licked?

‘Either that,’ added Kvasir, ‘or they will be confused by a demand for two more ales and a dish of mutton.’

But Radoslav looked at me and both of us knew, because we were more traders than the others, that the ship had held Starkad, or at least some of his men. Traders thrived on gossip: what cargo was going where, what prices for what goods in what ports. They sucked it up like mother’s milk and, to get it, they talked to every other trader they saw coming up against them or sailing down a route with them. Unless you looked like a warship, or a sleek hafskip, which could be more wolf than sheep, you hailed them all for news; you didn’t sheer away like a nervous maiden goosed behind her mother’s back.

Nor, if you were anyone but the Norse, did you run the Hellespont at night.

But it had vanished south and we followed. In the morning, Sighvat cast his bone runes on the wet aft-deck and tried to make sense of it, Short Eldgrim peering over his shoulder. In the end, Sighvat made his pronouncement and Gizur leaned on the steering oar as the sail cranked up; I saw we were taking the most likely trade route and wondered if that course had truly been god-picked or was Sighvat’s common sense.