Полная версия

The Wolf Sea

The Wolf Sea

Robert Low

To Lewis and Harris, two islands in a sea of troubles. I hope, one day, they enjoy what their grandfather has made for them.

Only the hunting hungry

Set sail on the wolf sea

Old Norse proverb

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

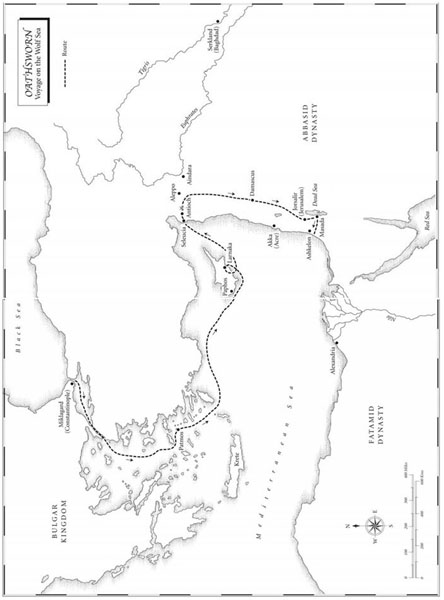

Maps

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

EPILOGUE

KEEP READING

HISTORICAL NOTE

The White Raven

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Wolf Sea

Copyright

About the Publisher

Maps

ONE

MIKLAGARD, the Great City, AD 965

His eyes flicked to the bundle in my hand, then settled on my gape-mouthed face like flies on blood. They were clouded to the colour of flint, those eyes, and his snake moustaches writhed as he sneered at me, the blow I had given him having done nothing except annoy him.

‘Big mistake,’ he snarled in bad Greek and moved up the alley towards me, hauling a seax the length of my forearm out from under his cloak.

I hefted the wrapped sabre, swung it and revealed how clumsy the weapon was in that single moment. He grinned; I backed up, slithering through black-rotted rubbish, wishing I had just gone my way and ignored him.

He was quick, too, darting in fast and low, but I had been watching his feet not his eyes and swung the bundle so that it smacked him sideways into the wall. I followed it with a big overarm hack, but missed. The bundled sword cut through the wrappings and struck sparks from the wall.

Showered with brick and plaster chips, he was alarmed, both at the near miss and the fact that there was now a sharp edge involved. I saw it in his eyes.

‘Didn’t expect this, did you?’ I taunted as we shifted and eyed each other. ‘Tell you what – you tell me why you are following me all over Miklagard and I will let you go.’

He blinked astonishment, then chuckled like a wolf who has found a crippled chicken. ‘You’ll let me go? I don’t think you realise who you are facing, swina fretr. I am a Falstermann and not one to take such insults from a boy.’

So I had been clever about him being a Dane, I thought. It was a pity I had not been so clever about taking him on. His feet shifted and I had been watching for that, so that when he swung I caught the seax on the shredded bundle, wincing at the blow. I turned my wrist to try and tangle his blade in cloth and almost managed to twist the seax free of his grasp. He was too old a hand for that, though, and I was too clumsy with the sword wrapped as it was.

Worse than that – even now I sweat with the shame of it – his oarmate came up behind me, elbowed the breath out of me and slammed me to the clotted filth of the alley. Then he plucked the wool-coddled sword from my fluttering hands, easy as lifting an egg from a nest and, dimly, I realised that’s what they had wanted all along. I was gasping and boking too much to do anything about it.

‘Time to row hard for it,’ this unseen one growled and I heard his steps squelching through the alley filth.

I was sure death had not been in the plan of this, but the man from Falster had blood in his eye and I had rain in mine, blurring the world. The cliff walls of the alley stretched up to frame a patch of indifferent grey sky and it came to me then that this would be the last sight I would see.

I did not want to die in a filthy alley of the Great City with the rain in my eyes. Not that last, especially, for the vision of the first man – the boy – I had killed came back to me, lying on a heath with his bloodless face and his eyes open and startled under little pools of rainwater.

The Falstermann loomed over me, breathing hard, the seax reversed for a downward thrust straight at my belt loop, rain pearling mistily on the pitted steel, sliding carelessly along the edge…

The rain, says Sighvat, will tell you all about a place if you know how to read it. The rain in a Norway pine wood is good enough to wash your hair in but, if a city is really old, it drips from the eaves with the grue of ages, black as pitch, harsh as a curse.

Miklagard, the Great City, was ancient and her pools and gutters spat and hissed like an evil snake. Even the sea here was corroded, heaving in slow, fat swells, black and slick and greasy as a wet hog’s back, glittering with scum and studded with flotsam.

I did not even want to be in this city and the gawping wonder of it had long since palled. Stumbling from the ruined dream of Attila’s silver hoard, those of the Oathsworn who survived the Grass Sea of the steppe had washed up here, after a Greek captain had been persuaded to take us. Since then, my great plan had been to load and unload cargo on the docks, husband what little real money we had, waiting for the rest of the Oathsworn to join us from far-off Holmgard and make a crew worth hiring for something better.

At the end of it all, distant as a pale horizon, was a new ship and a chance to go back for all that silver, a thought we hugged for warmth as winter closed in on Miklagard, drenching the Navel of the World in misery.

That black rain should have been warning enough, but the day the runesword was stolen from me I was wet and arrogant and angry at being followed all along in the lee of Severus’s dripping walls by someone who was either bad at it, or did not care if he was seen. Either way, it was not a little insulting.

On a clear day in Constantinople you could almost see Galata across the Horn. That day I could hardly see the man following me in the polished bronze tray I held up and pretended to study, as if I would buy it.

A face twisted and writhed in the beaten, rain-leprous surface, a stranger with a long chin, a thin, straggled beard, a moustache still a shadow and long, brown-red-coloured hair that hung in braids round the brow, some of them tied back to keep the hair from the blue eyes. My face. Beyond it, trembling and distorted, was my shadower.

‘What do you see?’ demanded the surly Greek owner of the tray and all its cousins laid out on a worn strip of carpet under an awning, heavy with damp. ‘A lover, perhaps?’

‘Tell you what I don’t see,’ I said with as sweet a smile as I could muster, ‘you gleidr gaugbrojotr. I don’t see a sale.’

He snorted and snatched the tray from me, his sallow face flushed where it wasn’t covered with perfumed beard. ‘In that case, fix your hair somewhere else, meyla,’ he snapped, which I had to admit was a good reply, since it let me know that he understood Norse and that I had called him a bowlegged grave-robber. He had called me little girl in return. From this sort of experience, I learned that the merchants of Miklagard were as sharp as their manners and beards were oiled.

I smiled sweetly at him and strolled off. I had learned what I needed: the bronze tray had revealed, beyond my face and watching me, the same man I had seen three different times before, following me through the city.

I wondered what to do, clutching the wrapped bundle of the runesword and chewing scripilita, the chickpea-flour bread, thin and crusty on top, glistening with oil on the bottom, wrapped in broadleaves and – wonder of wonders – thickly peppered. This treat, which was never seen further north than Novgorod, was so expensive beyond the Great City, thanks to the pepper, that it would have been cheaper to dust it with gold. The seductive taste of it and the cold was what made me blind and stupid, I swear.

The street led to a little square where the windows were already comfort-yellow with light as the early winter dark closed in. I had, even in so short a time, lost the wonder that had once locked my feet to the street at the sight of houses put one on top of the other and had eyes only for my tracker. I paused at a knife-grinder’s squeaking wheel, glanced back; the man was still there.

He was from the North, for sure, for he was taller than any others and clean-shaven but for the long snake moustaches, a Svear fashion that was much fancied by dandies then. He had long hair, too, which he had failed to hide well under a leather cap, and wore a cloak, under which could lurk anything sharp.

I moved on, past a stand where a woman sold chickpea flour and dried figs. Next to her, a man in a sleeveless fleece sold cheeses out of a single basket and, leaning against the wall and trying not to let their teeth chatter in the cold, a pair of girls tried to look alluring and show breasts that were red-blue.

The Great City is a miserable place in winter. It has the Sea of Darkness at its back and behind that the Grass Sea of the Rus; and it is a place of gloom and penetrating damp. There may be a flicker of late summer and even pleasant days at the start of the year, but you cannot count on sun, only rain, between the last days of harvest and the first ones of the festival of Ostara, which the Miklagard priests call Paschal.

‘Come and warm me,’ one of the girls said. ‘I can teach you how to make a beast with two backs if you do.’

I knew that trick and moved on, trying to keep the man in sight by turning and exchanging some good insults, then bumped into a carder of wool coming up the other way, demanding that people buy his mattress stuffings or risk freezing their babies by their carelessness.

The street slithered wetly down to the docks, grew crowded, sprouted alleyways and spawned people: bakers, sellers of honey, vendors of tanned leather for making cords, those selling the skins of small animals. This was not the fashionable end of Miklagard, this collection of lumpen faces and beggar hands. They were the halt, the lame and the poxed, most of whom would die in the cold of this winter unless they got lucky.

It was already cold in the Great City, cold enough to numb my senses into thinking to find out who this man was and why he followed me.

So I slid up one of the alleys and hefted the bundle that was the runesword, it being the only weapon I had besides an eating knife. My plan was to tap him with the cushioned blade of it as he passed, drag him in the alley and then threaten him with the sharp end until he babbled all he knew.

He duly obliged, even pausing at the mouth of the alley, having lost me and wondering where I had gone. If I had stayed in the shadows, I would have shaken him off, for sure – but I stepped out and rapped him hard on the head.

There was a clatter; he staggered and yelled: ‘Oskilgetinn!’, which at least let me know I had been right about him being from the North – though you could tell by his roar that it meant ‘bastard’ even if you couldn’t speak any Norse. The curse let me know he was at least prime-signed, if not fully baptised, since only Christ-followers worried about children born out of wedlock. A Dane, then, and one of King Harald Bluetooth’s new Christ-converts. I did not like what that promised.

The third thing I found out was that his cap was a metal helmet covered in leather and most of the blow had been taken on it. The fourth was that he was from Falster and I had made him angry.

That was what I learned. I missed many things, but the worst miss of all was his oarmate, coming up behind me and leaving me gasping in the alley, the sword gone and pearled rain dripping off the Falstermann’s blade, raised to finish me.

‘Starkad won’t be pleased,’ I gasped and the big Dane hesitated for long enough to let me know I had it right and he was a chosen man of an old enemy we had blooded before. Then I lashed out with my right leg, aiming for his groin, but he was too clever for that and whacked my knee hard with the flat of the blade, which he then pointed at me.

He wanted to kill me so bad he could taste it, but we both knew Starkad wanted me alive. He would want to gloat and wave the stolen runesword in my face, the one now long vanished up the alley. The Falstermann, wanting to be away himself, started to say a final farewell, which would have included how lucky I was and that the next time we met he would gut me like a fish.

Except that all that came out was ‘guh-guh-guh’ because a knife hilt had somehow appeared beneath his right ear and the blade was all the way into his throat.

A hand pulled it out as casually as if it were plucking a thorn and the hiss of escaping blood was loud, the splatter of it everywhere as the Dane collapsed like an empty waterskin.

Blinking, I looked up to what had replaced him against the yellow lantern glow of the window lights beyond the alley: a big man, shave-headed save for two silver-banded braids over each ear, wearing the checked breeks of the Irish and a tunic and cloak that was Greek. He also had a long knife and a tattooed whorl between his eyes, which I knew was the Ægishjalm, the Helm of Awe, a runesign supposed to send your enemies away screaming in terror with the right words spoken. I wished he would turn it off, for it was working well on me.

‘I heard him call you pig fart,’ he said in good East Norse, his eyes and teeth bright in the alley’s twilight. ‘So I reasoned he bore you no goodwill. And, since you are Orm the Trader, who has a crew and no ship, and I am Radoslav Schchuka, who has a ship and no crew, I was thinking my need for you was greater than his.’

He helped me up with a wrist-to-wrist grip and I saw that his bared forearm had several thick-welted white scars. I looked at the dead Dane as this Radoslav bent and rifled his purse, finding a few coins, which he took, along with the seax. Then it came to me that I should be dead in the alley and my legs trembled, so that I had to hold on to the wall. I looked up to see the big man – a Slav, for sure – cutting his own arm with the seax and realised the significance of the scars.

He saw my look and showed me his teeth in a sharp grin. ‘One for every man you kill. It is the mark of my clan, where I come from,’ he explained, then helped me roll the Dane in his cloak and back into the shadows of the alley. I was shaking now, but not at my narrow escape – it had come to me that the Dane would have gone his way and left me lying in the muck, alive – but at what had been lost. I could have wept for the shame of losing it, too.

‘Who were they?’ asked my rescuer, binding up his new scar.

I hesitated; but since he had painted the wall with a man’s blood, I thought it right that he knew. ‘A chosen warrior of one Starkad, who is King Harald Bluetooth’s man and anxious that he get something from me.’

For Choniates, I suddenly thought, the Greek merchant who had coveted that runed sword when he’d seen it. It was clear the Greek had sent Starkad to get it and would be unhappy about the death. The Great City had laws, which they took seriously, and a dead Dane in an alley could be tracked back to Starkad and then to Choniates.

Radoslav shrugged and grinned as we checked no one could see us, then left the alley, striding casually along as if we were old friends heading for a drink-shop. My legs shook, which made the mummery difficult.

‘You can judge a man by his enemies, my father always said,’ Radoslav offered cheerfully, ‘and so you are a great man for one so young. King Harald Bluetooth of the Danes, no less.’

‘And young Prince Yaropolk of the Rus also,’ I added grimly to see his reaction, since he was from that part of the world. Beyond a widening of his eyes at this mention of the Rus King’s eldest son there was silence, which lasted for a few footsteps, long enough for my racing heart to settle.

I was trying desperately to think, panicked at what had been lost, but I kept seeing that little knife come out of the Dane’s neck under his ear and the blood hiss like spray under a keel. Someone who could do that to a man is someone you must walk cautiously alongside.

‘What did he steal?’ Radoslav asked suddenly, the rain glistening on his face, turning it to a mask of planes and shadows.

What did he steal? A good question and, in the end, I answered it truthfully.

‘The rune serpent,’ I told him. ‘The roofbeam of our world.’

I brought him to our hov in a ruined warehouse by the docks, as you would a guest who has saved your life, but I did this Radoslav no favours. Sighvat and Kvasir and Short Eldgrim and the rest of the Oathsworn were huddled damply round a badly smoking brazier, talking about this and that and, always, about Orm’s plan to get them back to sea in a fine ship, so that they could be proper men again.

Except Orm didn’t have a plan. I had used up all my plans getting the dozen of us away from the ruin of Attila’s howe months before, paying the steppe tribes with what little I had ripped from that flooding burial mound – and had nearly drowned to get, the weight of it stuffed in my boots almost dragging me down.

I could not get rid of the Oathsworn after we had all been dumped on the quayside. Like a pack of bewildered dogs they had looked to me. Me. Young enough for any to call me son and yet they called me ‘jarl’ instead and boasted to any they met that Orm was the deepest thinker they had ever shared an ale horn with, even as I spun and hung my mouth open at the sheer size and wealth and wonder of the Great City of the Romans.

Here, the people ate free bread and spent their time howling at the chariot and horse races in the Hippodrome, fighting mad over their Blue or Green favourites and worse than any who went on a vik, so that city-wide riots were common.

The char-black scars from the previous year still marked where one had spread out, incited by opponents of Nikephoras Phocas, who ruled here. It had failed and no one knew who had fed the flames of it, though Leo Balantes was a name whispered here and there – but he and other faces were wisely absent from the Great City.

A black-hearted city right enough, which turned the slither from the gutters crow-dark so that we knew, even if the story of it curled on itself like a carved snake-knot, that cruelty squatted in Miklagard. Blood-feuds we knew well enough, but Miklagard’s treachery we did not understand any better than the city’s screaming passion for chariots and horses that raced instead of fought.

We were wide-eyed bairns on this new ship and had to learn how to sail it, fast. We learned that calling them Greek was an insult, since they considered themselves Romans, the only true ones left. But they all spoke and wrote in Greek and most of them knew only a little Latin – though that did not stop them muddying the waters of their tongue with it.

We learned that they lived in New Rome, not Constantinople, nor Miklagard, nor Omphalos, Navel of the World, nor the Great City. We learned that the Emperor was not an Emperor, he was the Basileus. Now and then he was the Basileus Autocrator.

We learned that they were civilised and we could not be trusted in a decent home, where we would either steal the silver or hump the daughters – or both – and leave dirty marks on the floors. We learned all this, not from kindly teachers, but from curled lips and scorn.

The slaves were better off than us, for they were fed and sheltered free, while we took miserable pay every day from a fat half-Greek, which would not let us afford either decent mead – even if we could find it here – or a decent hump. My stock of Atil’s silver was all but exhausted and still no plan had come to me yet and I wondered how long the Oathsworn would stomach this.

Singly and in pairs like half-ashamed conspirators all of them had approached me at one time or another since we had been here, all with the same question: what had I seen inside Attila’s howe?

I told them: a mountain of age-blackened silver and a gifthrone, where Einar the Black, who had led us all there, now sat for ever as the richest dead man in the world.

All of them had been there – though none but me inside it – yet none could find the way back to it, navigating themselves like a ship across the Grass Sea. I knew they also felt the fish-hook jerk of it, despite all that they had suffered, no matter that they had watched oarmates die there and had felt the dangerous, sick magic of that place for themselves.

Above all, they knew the curse that came from breaking the oath they had sworn to each other. Einar had broken it and they all saw what had become of that, so none slipped away in the night, abandoning his oarmates to follow the lure of silver. I was not sure whether this was from fear of the curse, or because they did not know the way, but they were Norsemen. They knew a mountain of riches lay out on the steppe and they knew it was cursed. The wrench between fear and silver-desire ate them, night and day.

Almost every night, in the quiet of that false hov, they wanted to look at the sword, that sinuous curve of sabre wrenched from Atil’s howe by my hand. A master smith had made that, a half-blood dwarf or a dragon-prince, surely no man. It could cut the steel of the anvil it was made on and was worked along the blade length with a rune serpent, a snake-knot whose meaning no one could quite unravel.

The Oathsworn came to marvel at that steel curve, the sheen of it – and the new runes I had carved into the wooden hilt. I had come late to the skill and needed help with them, but those were simple enough, so that any one of the Oathsworn could read them, even those who needed fingers to trace them and mumbled aloud.

Only I knew they marked the way back to Atil’s howe in the Grass Sea, sure as a chart.

A chart I had now managed to lose.

All of this swilled round in my head, dark as the water from Miklagard’s gutters, as I hunched through the rain towards our ratty warehouse hall, dragging the big Slav with me. The wind blasted and grumbled and, out across the black water, whitecaps danced like stars in a night sky.

‘You look like you woke up with the ugly one, having gone to bed with golden-haired Sif,’ Kvasir growled as I stumbled in, shaking rain off, slapping the piece of sacking that was my cloak and hood. His good eye was bright, the other white as a dead fish, with no pupil. He looked the big Slav up and down and said nothing.

‘Thor’s golden wife wouldn’t look at him,’ said a lilting voice. ‘Though half the Greek man-lover crews here would. Maybe that is the way ahead for us, eh, Orm?’

‘The way behind, you mean,’ jeered Finn Horsehead, jerking lewd hips and roaring at his own jest. Brother John’s look was withering and Finn subsided into mock humility, nudging his neighbour to make sure he had caught his fine wit.

‘Never be minding,’ Brother John went on, taking my elbow. ‘Come away here and sit you down. There’s a fine cauldron of…something…with vegetables in it that Sighvat lifted and Finn made with pigeons. And a griddle of flatbread. Enough for our guest, too.’

The men made room round the brazier and Brother John ushered us to a place, gave us bowls, bread and a wink. Radoslav looked at the food and it was clear a stew made of the Great City’s pigeons was not the finest meal he had eaten, nor – with the wind hissing through the warehouse, flaring the brazier embers – was this the best hall he had been in. But he grinned and chewed and gave every indication of being well treated. I took a bowl, but my mouth was full of ashes.