Полная версия

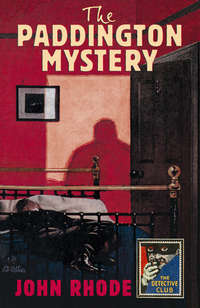

The Paddington Mystery

‘Examination of the body, however, revealed two salient facts. The first was that the left forearm bore minute marks—the number I have not been able to ascertain—such as might have been caused by a hypodermic syringe. From the position on the arm these marks might have been self-inflicted. The experts stated that the fact that no analytical or pathological traces of drugs could be discovered made it impossible that death could have been caused by some toxic injection. The second fact was that the deceased suffered from an affection of the heart of long standing, and of a nature which frequently terminates fatally. The existence of this heart affection caused one of the experts to put forward the suggestion that the marks on the forearm were the result of self-injection of some drug prescribed to relieve the heart, and that these injections had been made sufficiently long before death for all traces of the drug used to have vanished. I think that is a fair summary of the medical evidence?’

Harold nodded. He had learnt by now that interruptions of the Professor’s train of thought were not welcome.

‘Very well, then,’ continued the Professor, ‘you will agree, I think, that this evidence is mostly negative. Pressed to account for the fact that the man was dead and not alive when found, the medical witnesses—I say witnesses, for the police surgeon had sought the assistance of a Home Office expert—suggested that the deceased died of heart failure, brought on by sudden immersion on a cold night affecting an already-weakened organ. That the man died of heart failure was patent; I suppose most people die because the heart ceases to function for some cause or other. Whether this man’s heart failed for the causes alleged, I cannot say. There may have been facts supporting the experts’ view which are hidden from the mere lay mind. Were I to give an opinion, I should say it was a mere guess, although an extremely plausible one. In any case, the coroner and his jury seized upon it, and their verdict was the result.

‘The next point of enquiry is obviously the time when the man died. The police surgeon, who saw the corpse at about five o’clock in the morning, expressed an opinion that the man had been dead not less than about nine or ten hours. Again, I have no knowledge or experience in such a matter, and we may provisionally accept this estimate as correct. In which case, the man may be assumed as having been dead by eight or nine o’clock the previous evening. According to your evidence you left your rooms at about four o’clock that evening, at which time, to your knowledge, the rooms contained no man, alive or dead.’

‘That is so, sir,’ replied Harold, seeing that the Professor paused, as though for confirmation. ‘I fancy that the police had a vague suspicion that the body had been there all the time, since the doctors could only say that the man had been dead not less than eight or nine hours and not more than about twenty-four.’

‘Possibly, possibly,’ agreed the Professor. ‘But certain other evidence, which, I confess, interests me far more than the question of the identity of the deceased, seemed to point in quite another direction. I mean the evidence concerning the means by which the corpse obtained access to your rooms. As you know, I have never visited Number 16, Riverside Gardens myself, but I received a description, an inadequate one, I admit, from a friend who has been there.’

‘Inspector Hanslet again, sir?’ suggested Harold.

‘No,’ replied the Professor. ‘His mind was already made up. I wanted the description from someone who was unaware of the details which had been discovered. Evan Denbigh was able to supply me with the outline of what I required.’

‘Denbigh!’ exclaimed Harold, with some embarrassment. ‘Oh yes, of course, he was there once, about six months ago. He came—’

Professor Priestley waited for the end of the sentence, but Harold had relapsed into silence.

‘He told me why he went,’ he said quietly. ‘He was one of your friends who thought that you were making a fool of yourself. I fancy he went to see if you could not see reason.’

‘Well, as a matter of fact, that’s what he did come for,’ agreed Harold. ‘Jolly decent he was about it, too, really. He can’t have seen much of the place, though. I was dressing for dinner, I had half my clothes flung about the sitting-room, and after he’d been there about ten minutes I went into the bedroom to wash and left him spouting to me through the door. He never saw the bedroom, where I found the body, at all.’

‘So he told me,’ replied the Professor. ‘That is exactly why I want to see it for myself. Will you take me there, my boy?’

‘Rather, sir!’ exclaimed Harold. ‘When would you like to go?’

Professor Priestley considered for a moment. ‘I shall be disengaged at three o’clock tomorrow afternoon,’ he replied. ‘Now, my boy, I do not wish to raise your hopes unduly, but this case does not appear to me to be so hopeless as it seems. Good-bye until tomorrow.’

CHAPTER III

HAROLD returned to Riverside Gardens rather despondently. What he had expected as a result of his visit to Professor Priestley he hardly knew. It had been a sub-conscious impulse that had driven him to seek his father’s old friend, an instinct to seek protection under the mantle of unquestioned respectability. His reception, contrary to what he had expected, had been warm, had somehow led him to expect an immediate dissipation of the clouds that had surrounded him. Whereas the result of their prolonged interview seemed to leave the matter exactly where it had stood before.

Remember, Harold’s desire to solve the mystery was very keen. He had been through a remarkably unpleasant ordeal, had been an object of strong suspicion, and had been put through a very fine mill of inquisition. He had come out of it with hardly a shred of decency left to him; the papers had published full reports of the inquest, at which he had figured in none too favourable a light. And, worst of all, although the verdict had exonerated him from the accusation of having caused the man’s death, he was conscious that there was a pretty strong notion abroad that he knew more about the business than he had divulged.

He felt like an outlaw, shunned by the whole world. Return to his former life was impossible; the Naxos Club had been raided and dispersed, notoriously as the result of his enforced account of his doings on that fatal evening, and he could scarcely expect his old friends to welcome him with open arms. A return to the world of respectability was impossible while the stigma of intangible wrong-doing still attached to him. The only way out that he could see was to discover the truth of the mysterious circumstances that had involved him in their toils. Professor Priestley had led him to believe that this was possible, and had left him with nothing more cheering than that the business was not so hopeless as it looked!

The first thing Harold noticed as he opened the gate of Number 16, Riverside Gardens, was that the door of Mr Boost’s shop was open. As he came up the path the proprietor himself came out and barred his further passage, silent, accusing.

‘Good evening, Mr Boost,’ said Harold politely. ‘So you’re back again?’

The man made no reply, but stood looking at him malevolently. He was tall and thin, with a pronounced stoop, sharply-cut features and a curiously intense look in his eyes. He wore an untidy-looking tweed suit but the most striking thing about him was an enormous red scarf, which did duty both as a collar and tie, and an equally pretentious red handkerchief, a good half of which protruded from the side pocket of his coat. He was obviously not the sort of person to disguise his political convictions.

This individual regarded Harold for some moments in silence. Then he suddenly turned and led the way into the shop, beckoning to Harold to follow him. He closed the door behind them, then, for the first time, spoke.

‘What did you do it for, comrade?’ he asked, in a surprisingly deep voice, that seemed to come from some strange vocal organs concealed within his narrow chest.

Harold turned upon him indignantly. ‘What the devil do you mean?’ he replied angrily. ‘You seem to know all about it. Haven’t you heard that the police found that I had nothing to do with it? I shouldn’t wonder if you knew more about it than I do.’

‘Damn the police!’ exclaimed Mr Boost. ‘They’re only the servants of a tyrannical capitalism. The first thing we shall do will be to discard them and set up Red Guards who’ll know their business instead. Police, indeed! Why, they had the sauce to come to me in Leicester where I was doing a lot of business and badger the life out of me. Where was I that night? Did I know the man who had been found dead in my house? Showed me his photograph and description and cross-questioned me till I told them what I thought of them. I wouldn’t give a curse for anything the police might think.’

Harold smiled. He recalled a remark of Inspector Hanslet. ‘Boost? Oh, yes, we know all about him. He’s harmless enough, but we’ll have him looked up, though, for all that.’ But he refrained from repeating it to his landlord.

‘What your idea was I don’t know and I don’t want to know,’ continued Mr Boost. ‘You seem to have scrambled out of it, and I suppose that’s all you care about. But you can’t expect me to thank you for bringing every silly fool in London to gape round this place. I thought you wanted to lie low when you came here.’

He went into the back room, still grumbling, and Harold, seeing the futility of trying to persuade him of his innocence, took the opportunity of going up to his own rooms. He spent the evening trying to write, and then at last, giving up the task in despair, went to bed and slept fitfully, dreaming impossible dreams in which the dead man, Boost, Professor Priestley and a host of minor characters came and went, mocking him, scorning him for the outcast he was.

At nine o’clock Mrs Clapton, from Number 15 over the way, thundered at his door, as was her custom. When he had first come to Riverside Gardens he had engaged her to come in for an hour every morning to tidy the place up. The Paddington Mystery, as the headlines had called it, had raised her to the seventh heaven of delight. In an incautious moment Inspector Hanslet had called upon her to ask a few questions, and had only succeeded in escaping after an hour of breathless volubility which had left his head in an aching whirl. Since that moment she had regaled her neighbours and all whom she could prevail upon to listen to her with a torrent of eloquence. As the only person besides the central figure who had access to the scene of the discovery, she poured forth in an unceasing stream the little she knew and the enormous volume of what she conjectured.

But this morning Harold was in no mood to listen to her theories or her remarkably frank comments. He put on a dressing-gown and let her in, then returned again to bed, leaving her the run of the sitting-room. For her regulation hour she busied herself in moving the furniture about, then, after making several unsuccessful attempts to engage Harold in conversation through the closed door, she departed, firmly convinced that her employer had something discreditable to conceal. ‘It’s hawful the life that young man leads,’ she was wont to whisper. ‘I’ve seen him go in with girls after dark—you mark my words, there’s somethink be’ind it all!’

Harold waited for the door to bang behind her, then wearily made up his mind to get up. He was half dressed, when once more a loud and insistent knocking on the door disturbed his train of thought.

With a muttered imprecation he went down stairs, to find Boost standing on his doorstep.

Harold frowned. He and his landlord had always got on pretty well hitherto. Boost had never abandoned the hope of converting his tenant to the doctrines of Communism, and had called upon him at all sorts of hours for that purpose. The man’s energy and ferocity had amused him; he had regarded him as a harmless crank whose proper field of action was surely Soviet Russia. But now he had other things to think of, and was in no mood for a lecture upon the iniquities of the bourgeois and the advantages of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat.

‘Good morning, Mr Boost,’ he said coldly. ‘What can I do for you? I’m going out as soon as I’ve finished dressing.’

‘You and I’ve got to have a word first,’ replied Mr Boost truculently. ‘There’s a question or two to which I want an answer.’

Harold shrugged his shoulders and led the way upstairs. He might as well hear what the man had to say and get it over.

Mr Boost settled himself in Harold’s best chair and plunged into his subject without delay. ‘Look here!’ he said sharply. ‘I want to know what your game was the other night.’

Harold sighed wearily. ‘Oh, Lord, you know all about that!’ he exclaimed. ‘I suppose you read the papers?’

‘Yes, I read them right enough,’ replied Mr Boost. ‘I don’t want to pry into your affairs so long as they don’t concern me. When they do, I’m going to have the truth. What happened to my bale of goods, I’d like to know?’

Harold stared at him in amazement. ‘Your bale of goods?’ he repeated. ‘What the devil are you talking about? What bale of goods?’

Mr Boost regarded him suspiciously. ‘I reckon you know more about it than I do,’ he said. ‘Especially as it happens I’ve never seen it.’

‘Look here, Mr Boost. I don’t know what the hell you’re talking about,’ replied Harold, now thoroughly roused. ‘I haven’t got anything of yours, you can search the place if you like. And when you’ve finished I’ll trouble you to clear out and leave me in peace.’

Mr Boost laughed scornfully. ‘Oh, I don’t suppose you’ve got it here,’ he said. ‘But it’s like this. I’m not such a fool as to believe that a man comes and dies in these rooms without your knowing something about it. And when a bale of goods of mine disappears on the same night, I can’t help thinking that you know something about that, too.’

‘How do you know it disappeared that night?’ enquired Harold sharply.

‘Did you see it leaning up against my door under the porch when you came home that night?’ replied Mr Boost aggressively. ‘Or were you too beastly drunk to notice anything?’

Harold paused a moment. ‘I won’t swear about when I first came in,’ he said. ‘It was nearly pitch dark, you know. But I know jolly well that there was nothing there when I came back with the police. Someone would have seen it if there had been. And there wasn’t anything there when I went out that evening.’

‘Of course there wasn’t,’ replied Mr Boost testily. ‘It hadn’t been delivered then. Well, I’ll have to tell you what happened, I suppose. You get my stuff back from your pals, and I won’t ask any questions. That’s fair.’

Harold started to make an indignant refutation, but Mr Boost silenced him.

‘Now, just you listen,’ he interrupted. ‘I’ve got some stuff coming down from Leicester, and I’ve just been up to see George, who keeps a van up along the Harrow Road and does a bit of carting for me now and then. I’ve fixed up with him to fetch this stuff from the station, and when I was leaving him he says, “Did you find that lot all right I left for you the other evening, Mr Boost?”’

‘“What other evening?” I said. “You haven’t done a job for me for the last couple of months, George!”

‘“Why, the evening before that there body was found in your house, Mr Boost,” he said. “That’s how I remember the evening it was. I must have been along at your place about an hour or so before the chap broke in.”

‘Well, I knew of nothing coming while I was away, though it does sometimes happen that a friend of mine in the trade sends something along which he knows I can do with. Very often the carman, if he knows me, leaves the stuff outside the door. It’s safe enough in the front garden, especially if it’s heavy, as it usually is. You’ve seen stuff standing under the porch before now, haven’t you?’

Harold nodded. ‘Yes, but I’ve seen nothing there while you’ve been away,’ he said.

Mr Boost looked at him suspiciously. ‘Well, it wasn’t there when I came back, and so I told George. “What was it, anyhow, and where did it come from?” I asked him.

‘“I don’t know what it was, but it was middling heavy,” he said. “I got a message from old Samuels that he had some stuff for you, and I was to be particular and fetch it that very evening. So down I went to Camberwell, picked up the stuff about four, and was back with it here between five and six.”

‘Well, I didn’t know of anything old Samuels had for me, but there was nothing in that. He’s a comrade, or he used to be, he’s got a bit slack lately. Calls himself Samuels, but his real name’s Szamuelly. One of his relations was one of Lenin’s men, and fought a glorious fight for the cause in Hungary. Killed himself rather than be caught when the capitalists put the bourgeois back again. Never mind, that won’t last long. The whole of Europe is already on the brink—’

‘But this man Samuels and his bale of goods?’ interrupted Harold, feeling that an account of anything that happened on that fatal evening was preferable to an oration on Bolshevism.

Mr Boost checked himself and returned to his story. ‘Well, George told me that he got the message—there’s a telephone belonging to a man in his yard, and he’ll take a message for George from one of us dealers—and went down to Samuels’ place. He didn’t see the old man himself, but heard him wheezing and coughing in the back shop. When George raps on the counter, out comes Samuels’ nephew, a half-witted sort of chap who comes and lives with his uncle when he can’t get a job anywhere else. The nephew shows him a bale done up with mats and rope, and between them they got it into the van. George says it was about six foot long, and weighed best part of a couple of hundredweight. “Uncle says if Mr Boost isn’t in, you can leave it under the porch, it won’t hurt in the open for a night or two,” the nephew tells him. George asks if he can have his money, twelve-and-six, for the job. The nephew goes into the back room, and George hears the old man coughing and wheezing again. I’ll bet he did, too.’

Mr Boost allowed his austere frown to melt into a smile at the idea. ‘Old Samuels is worth a lot of money,’ he explained, ‘but it’s like drawing a tooth to get a shilling out of him. By and by the nephew comes back, and gives George his twelve-and-sixpence exact, not a penny more for a drink, you may bet. George comes straight here, or so he says, carries the stuff up to the door, and props it under the porch. And what I want to know is, what’s become of it?’

Mr Boost fixed his fiery eye upon Harold, as though he expected him to confess immediately to the theft of this bale of goods. But for a moment Harold made no reply. There seemed no reason to doubt the truth of the story—in any case it could easily be verified by referring to George or to Mr Boost’s friend, old Samuels. It was just possible that the disappearance of this bale was in some way connected with the other mysterious happening of that eventful night.

‘Look here, Mr Boost,’ he said at last. ‘I may be a pretty fair rotter, but at least I haven’t tried my hand at theft, as yet. Besides, if I wanted to steal a bale of that size and weight, I shouldn’t know how to set about it or where to dispose of it. For that matter, I can account for every minute of my time that evening. I give you my word I know nothing of the matter. Will that do?’

Mr Boost’s frown relaxed a little. ‘I’m not saying you took it,’ he conceded. ‘But there were some pretty queer happenings about here that night, and I reckon that you know more about them than you’re prepared to say. How do I know that the disappearance of that bale hasn’t got something to do with them?’

‘Well, Mr Boost, I can only assure you that nobody wants to know what happened that night more than I do,’ replied Harold. Then he added maliciously, ‘Why don’t you tell the police about it? They’d be glad to help you, I dare say.’

‘Police!’ exclaimed Mr Boost contemptuously. ‘I don’t want them fooling about with my business. I don’t recognise their right to interfere in a free man’s affairs. No, I’m going to find out about this myself, I am.’

‘In that case, I shall be very pleased to give you all the help I can,’ replied Harold. ‘I have an idea if we could find out what happened to your bale of goods, we should learn something about the man I found dead in my bed. What was in this precious bale, anyhow?’

Mr Boost shook his head. ‘I don’t know,’ he said. ‘Old Samuels’ nephew didn’t tell George. Don’t suppose he knew; the old man keeps his business pretty much to himself. He knew I should find out what it was when I opened it, and that was good enough for him.’

‘Was it likely to have been anything of any great value?’ suggested Harold.

‘Old Samuels wouldn’t have told George to leave it in the porch if it had been. Besides, he’d have written to me by now asking for the money. He doesn’t like parting with anything that’s worth much, doesn’t that old man.’

‘Then the only way to find out what was in the bale is to ask old Samuels himself,’ said Harold. ‘Why don’t you write him a note and find out? You can’t begin to trace the stuff until you know what it was.’

Mr Boost shook his head. ‘No, I don’t care to write,’ he replied. ‘Like as not the old man wouldn’t answer, or if he did, would send a bill for the stuff. And I can’t very well go and see him today, I don’t want to leave the place till George has delivered that lot from Leicester.’

An idea struck Harold and he blurted it out before he had time to consider the consequences it might entail.

‘Look here, Mr Boost, I’m as interested in the fate of this bale of goods as you are, only for a slightly different reason. Someone must have taken it away that night, and it is just possible that that someone could throw some light on what I want to know. If you like, I’ll go to Camberwell and see old Samuels for you.’

Mr Boost considered for a moment without replying. ‘Couldn’t do no harm,’ he said at last, rather reluctantly. ‘If you can get anything at all out of the old man, that is. He’s as close as an oyster. I’m beginning to believe that your story’s right, that you’ve been fooled over this night’s business same as I have. Perhaps that fellow did break in after my stuff. But if so, what did he take the trouble to climb up to your rooms for? Why break in if the stuff he wanted was already outside? How did he get it away if he was dead? No, it beats me, but it may not be your fault, after all. Yes, you can go and see old Samuels, if you like.’

‘Thank you, Mr Boost, I will,’ replied Harold gravely. ‘What sort of a chap is the old man, anyway?’

‘He’s a queer old fish,’ replied Mr Boost. ‘Always grumbling and grousing under his breath. You can’t tell what he’s saying, he mumbles so. To look at him, you wouldn’t think he had a bean in the world, though I know for a fact he’s got some thousands locked up in a tin box in the back room. He doesn’t know I know that, or I believe he’d murder me. He’s a stingy old skinflint as ever you’ve heard of; I’ve only known him wear one suit of clothes all the time I’ve known him, all loose and baggy, with about half a dozen ragged waistcoats underneath it. You can hardly see his face, he’s all shaggy like a bear, long hair, whiskers and beard, which haven’t ever been combed, by the look of it. Like as not, unless you tell him you come from me, he’ll mumble and cough at you and tell you to mind your own business.’

‘I’ll risk that,’ said Harold with a smile. ‘I’ll be off to see old Samuels or Szamuelly tomorrow afternoon. What’s his address, by the way?’

‘Thirty-six, Inkerman Street, Camberwell,’ replied Mr Boost. ‘A tram from Victoria will take you pretty close to the place. It’s a little shop up a side street, not unlike this, only he’s more stuff in his window. He does a bit of retail trade sometimes.’

‘All right, I’ll find it,’ said Harold. ‘Any message for him?’

‘No, I don’t think he wants my love,’ said Mr Boost sourly. ‘You may not find him in, he goes about the country buying sometimes, same as I do. I rather thought he’d be in Leicester the other day. Don’t you go and tell him I lost that stuff, if you see him.’