Полная версия

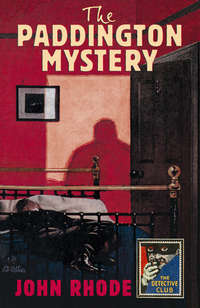

The Paddington Mystery

THE PADDINGTON MYSTERY

A STORY OF CRIME

BY

JOHN RHODE

PLUS

‘THE PURPLE LINE’

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

TONY MEDAWAR

Copyright

COLLINS CRIME CLUB

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Geoffrey Bles 1925

‘The Purple Line’ first published in the Evening Standard 1950

Copyright © Estate of John Rhode 1925, 1950

Introduction © Tony Medawar 2018

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008268848

Ebook Edition © June 2018 ISBN: 9780008268855

Version: 2018-02-06

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

The Paddington Mystery

Introduction

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter XV

The Purple Line

Keep Reading …

The Detective Story Club

About the Publisher

THE PADDINGTON MYSTERY

‘THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB is a clearing house for the best detective and mystery stories chosen for you by a select committee of experts. Only the most ingenious crime stories will be published under the THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB imprint. A special distinguishing stamp appears on the wrapper and title page of every THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB book—the Man with the Gun. Always look for the Man with the Gun when buying a Crime book.’

Wm. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., 1929

Now the Man with the Gun is back in this series of COLLINS CRIME CLUB reprints, and with him the chance to experience the classic books that influenced the Golden Age of crime fiction.

INTRODUCTION

THE writer best known as ‘John Rhode’ was born Cecil John Charles Street on 3 May 1884 in the British territory of Gibraltar. His mother was descended from a wealthy Yorkshire family and his father was a distinguished Commander in the British Army who—at the time of his son’s birth—was serving in Gibraltar as Colonel-in-Chief of the Second Battalion of Scottish Rifles.

Shortly after his birth John Street’s parents returned to England where, not long after John’s fifth birthday, his father died unexpectedly. John and his widowed mother went to live with her father, and in 1895 John was sent to Wellington College in Berkshire. John did well in his academic studies and, perhaps unsurprisingly given the approach he took to detective stories, he excelled in the sciences. At the age of 16, John left school to attend the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich and, on the outbreak of the Great War, as it was then called, he enlisted, rising to the rank of Major by March 1918. While he was wounded three times, John Street’s main contribution to the war effort concerned the promulgation of allied propaganda, for which he was awarded the Order of the British Empire in the New Year Honours List for 1918 and also the prestigious Military Cross. As the war came to an end John Street moved to a new propaganda role in Dublin Castle in Ireland, where he would be responsible for countering the campaigning of the Irish nationalists during the so-called war of Irish independence. But the winds of change were blowing across Ireland and the resolution—or rather the partial resolution—of the ‘Irish Question’ would soon come in the form of a treaty and the partition of the island of Ireland. As history was made, Street was its chronicler, at least from the British perspective.

During the 1920s, other than making headlines for falling down a lift shaft, John Street spent most of his time at a typewriter, producing a fictionalised memoir of the war and political studies of France, Germany, Hungary and Czechoslovakia, as well as two biographies. He also wrote a few short stories and articles on an eclectic range of subjects including piracy, camouflage and concealment, Slovakian railways, the value of physical exercise, peasant art, telephony, and the challenges of post-war reconstruction. He even found time to enter crossword competitions and, reflecting his keen interest in what is now known as ‘true crime’, he published the first full-length study of the trial of Constance Kent, who was convicted for one of the most gruesome murders of the nineteenth century at Road House in Kent. John also found time to write three thrillers and a wartime romance. However, while his early books found some success, the Golden Age of detective stories had arrived, and he decided to try his hand at the genre.

The first challenge was to create a great detective, someone to rival the likes of Roger Sheringham and Hercule Poirot, with whose creators John Street would soon be on first name terms. Street’s great detective was the almost supernaturally intelligent Lancelot Priestley, a former academic, who in the words of the critic Howard Haycraft was ‘fairly well along in years, without a sense of humour and inclined to dryness’. Dr Priestley’s first case, published in October 1925, would be The Paddington Mystery. Doctor—or rather Professor—Priestley was an immediate success, and Street was quick to respond, producing another six novels in short order. As well as Priestley, Street’s ‘John Rhode’ novels often feature one or both of two Scotland Yard detectives, Inspector Hanslet and Inspector Jimmy Waghorn who would in later years appear without Priestley in several radio plays and a short stage play.

By 1930, John Street was no longer just a highly decorated former Army Major with a distinguished career in military intelligence—he had now written a total of 25 books under various pseudonyms. He was 45 years old, and he was just getting started. As ‘John Rhode’ he would produce a total of 76 novels, all but five of which feature Dr Priestley and one of which was based on the notorious Wallace case. But, while writing as ‘John Rhode’, Street also became ‘Miles Burton’, under which pseudonym he wrote 63 novels featuring Desmond Merrion, a retired naval officer who may well have been named after Merrion Street in Dublin. There also exists an unfinished and untitled final novel, inspired it would appear by the famous Green Bicycle Case. The ‘Rhode’ and ‘Burton’ detective mysteries are similar, but whereas Priestley is generally dry and unemotional, Merrion is more of a gentleman sleuth in the manner of Philip Trent or Lord Peter Wimsey. Both Merrion and Priestley are engaged from time to time by Scotland Yard acquaintances, all of whom are portrayed respectfully rather than as the servile and unimaginative policemen created by some of Street’s contemporaries.

But two pseudonyms weren’t enough and, astonishingly, ‘Rhode’ also became ‘Cecil Waye’, a fact that was only discovered long after his death. For the four ‘Cecil Waye’ books, Street created two new series characters—the brother and sister team of Christopher and Vivienne Perrin, two investigators rather in the mould of Agatha Christie’s ‘Young Adventurers’, Tommy and Tuppence Beresford. The Perrins would appear in four novels, which are now among the rarest of John Street’s books. Curiously, the first ‘Cecil Waye’ title—Murder at Monk’s Barn—is a detective story very much in the style that he would use for most of his ‘John Rhode’ and ‘Miles Burton’ books. However, the other three are metropolitan thrillers, with less than convincing plots, especially the best-known, The Prime Minister’s Pencil.

As well as writing detective stories, John Street was also a member of the Detection Club, the illustrious dining club whose purpose, in Street’s words, was for detective story writers ‘to dine together at stated intervals for the purpose of discussing matters concerned with their craft’. As one of the founding members, Street’s most important contribution was the creation of Eric the Skull, which—showing that he had not lost his youthful technical skills—he wired up with lights so that the eye sockets glowed red during the initiation ceremony for new members. Eric the Skull still participates in the rituals by which new members are admitted to the Detection Club. Street also edited Detection Medley, the first and arguably best anthology of stories by members of the Club, and he contributed to the Club’s first two round-robin detective novels, The Floating Admiral and Ask a Policeman, as well as the excellent true crime anthology The Anatomy of Murder and one of their series of detective radio plays. Street was also happy to help other Detection Club members with scientific and technical aspects of their own work, including those giants of the genre Dorothy L. Sayers and John Dickson Carr; in fact Carr later made Street the inspiration for his character Colonel March, head of The Department of Queer Complaints.

In an authoritative and essential study of some of the lesser luminaries of the Golden Age, the American writer Curtis Evans described John Street as ‘the master of murder means’ and praised his ‘fiendish ingenuity [in] the creative application of science and engineering’. For Street is genuinely ingenious, devising seemingly impossible crimes in locked houses, locked bathrooms and locked railway compartments, and even—in Drop to his Death (co-authored with Carr)—a locked elevator. Who else but Street could come up with the idea of using a hedgehog as a murder weapon? A marrow? A hot water bottle? Even bed-sheets and pyjamas are lethal in his hands.

Street’s books are also noteworthy for their humour and social observations, and he doesn’t shy from defying some of the expectations of the genre: in one novel Dr Priestley allows a murderer to go free, and in another the guilty party is identified and put on trial … but acquitted.

John Street died on 8 December 1964. Half a century later, while he is not as highly regarded by critics as, say, Christie, Carr or Sayers, he remains one of the most popular writers of the Golden Age, producing more than 140 of what one fan neatly described as ‘pure and clever detective stories’. Not a bad epitaph.

TONY MEDAWAR

November 2017

CHAPTER I

‘STEADY, sir!’ exclaimed the taxi-driver sharply.

Harold Merefield made a wild clutch at the open door of the vehicle and managed to save himself from falling into the roadway.

‘It—it’s all right,’ he stammered. ‘Beastly shlippery tonight, must be a frost. Wosher fare?’

The taxi-driver lit a match and gazed speculatively at his clock. The young toff was too far gone to have any inkling of time or distance.

‘Eight and ninepence,’ he declared, with the air of a man who states an ascertained and incontrovertible fact.

Harold Merefield fumbled in his pocket and produced a ten-shilling note. ‘Here you are,’ he said magnificently. ‘I don’t want any change.’

He suddenly let go of the door handle, as though it had become too hot for him to hold, and started off rapidly down the Harrow Road. The taxi-driver watched his course with an appraising eye.

‘That’s a rum set-out,’ he muttered. ‘Bloke picks me up in Piccadilly at ’alf past two in the morning, and tells me to drive ’im to Paddington Register Office. Drunk as a lord, too. An’ when I takes ’im there, blowed if ’e don’t make tracks straight for the perlice station, like as though he wants to give ’imself up for drunk and disorderly. No, he don’t, though, he’s got ’is wits about ’im more than I gave ’im credit for. Well, it’s no concern o’ mine. Time I ’opped it.’

He put his lever into gear, swung his wheel round, and disappeared in the direction of the Edgware Road.

The object of his solicitude, although he had certainly set out towards the police station, had turned off to the left past the gate of the casual ward of the workhouse, planting his feet with the severe determination of one who dares his conscience to declare that he is drunk. It was obvious that he had often trodden this way before; an onlooker, had there been such, might have gained the impression that his legs, accustomed to this route, needed no guidance from a bemused brain. They steered an uncertain course down the middle of the road taking corners warily, like a ship swinging round a buoy, and turned at last into a narrow cul-de-sac adorned with a battered sign upon which, by daylight, might have been deciphered ‘Riverside Gardens.’

But, as it happened, there were no onlookers, as was perhaps natural at three a.m. of a winter’s night. The evening had been foggy; one of those late November evenings when a general gloom settles down upon London, producing not the merry blind-man’s-buff of a true pea-souper, but an irritating, choking opacity through which the gas-lamps show as vague blurs of light, beneath which the shadowy traffic roars and jolts. A thoroughly unpleasant evening, making the luxury of warmly-carpeted rooms, illuminated discreetly by shaded electric lamps, seem all the more desirable by contrast with the chill discomfort of the cheerless streets.

So Harold Merefield had felt as he had entered the portals of the Naxos Club, that retiring establishment which veiled its seductions behind the dingy brick front of an upper part in a modest Soho street. Upon leaving it his reflections were no longer meteorological, but it was somehow borne in upon him that the fog had lifted, to be replaced by a fine and exceedingly chilly drizzle. Having found a taxi, and persuaded the fellow that he really did want to be driven to the Paddington Register Office—a matter of some difficulty, since the man had expressed disgusted scorn at such a destination—‘’Ere, come off it. ’Tain’t open at this time o’ night, and besides, you ain’t got no girl with you’—he had flung himself down into the corner, the easier to meditate upon his grievance. Oh, yes, it had been a jolly night enough, he was ready to admit that, jolly enough for the other fellows, that is. His own evening had been spoilt, for what was the fun of drinking by oneself, or with such of the girls who chose to offer themselves as temporary solaces to his loneliness? Vere, who had never before failed him, had unaccountably absented herself, without a word of warning, without even ringing him up to make her excuses. Of course, he might have gone to her rooms and fetched her, but why the devil should he, on a night like that? He wasn’t going to run after any girl, she could come or not as she chose. Next time he wouldn’t turn up himself, and we’d see how she liked that.

The stopping of the taxi had interrupted the train of his thought. His stumbling exit provided him with a new sense of grievance, as he became conscious that he had barked his shins. He felt himself a deeply ill-used man as he turned into Riverside Gardens and splashed unsteadily through the puddles which had collected on its disreputable paving. On either side of the short road, a backwater, hidden away in this remoter part of Paddington, the unkempt front gardens of a row of tumble-down two-storied houses stood, dark and smelling of the rubbish they harboured. He passed them all, and turned in through the gateway in the low wall of the last garden on the right-hand side. He had reached home safely.

Number 16, Riverside Gardens was, perhaps, the least decayed of the row that bore this surprising name. From the narrow pavement of the cul-de-sac an asphalt path some ten yards long led through what had once been a garden, but was now merely a plot of waste land covered with rubbish, to a doorway screened by a ramshackle porch. You mounted a couple of steps, and from the top of these the mystery of the name was revealed. A low wall bounded the end of the cul-de-sac and the side of the garden; on the other side of this, dank, ill-odorous and forbidding, lay the stagnant waters of the Grand Junction Canal, an inky liquid besprinkled with nameless flotsam. It only needed sufficient imagination to see in this melancholy ditch a river, and in the desolate patches of earth before the houses a wealth of vegetation and the unexpected nomenclature became obvious.

Your enquiring mind thus set at rest, you explored the doorway in front of you. You had a choice of two panels on which to rap—there was no sign of a bell, merely the narrow orifice of a Yale lock on either door. One of these doors led into what was known by courtesy as ‘The Shop’; so much you could guess by peering through the filthy panes of the window on your left. Above this door you might have deciphered the name ‘G. Boost.’ From your necessarily limited survey through the window you would probably gather that Mr Boost’s shop was devoted to the accumulation of all the rubbish that the march of progress has banished from the Victorian middle-class home.

It was into the lock of the other door that Harold Merefield, not without some difficulty, occasioned by the reluctance of his hand to find the more distinct of the images conveyed to his brain by his eyes, inserted his key. The door swung open, revealing a narrow flight of stairs, rather surprisingly covered with a worn but excellent carpet. These heavily surmounted, the tenant of this curious dwelling reached a small landing, off which two doors led. He opened that towards the front of the house, stumbled in, knocked clumsily against various pieces of furniture, and at length, after much vain groping, accompanied by muttered curses, found a box of matches and struck a light. This done, he flung his coat in a heap upon the floor, and sank into a remarkably comfortable and well-cushioned chair.

The spectacle of a young man in impeccable evening dress sitting in a luxuriously-furnished room in the heart of a particularly ill-favoured slum might reasonably have been considered a remarkable portent. But then, Harold Merefield—his name, by the way, was pronounced Merryfield, a circumstance which had led to his being known as ‘Merry Devil’ to certain of his boon companions at the Naxos Club—was, in every respect, a remarkable young man. It had always been understood that he was to succeed his father, an elderly widower and a respected family solicitor, in his provincial practice. However, on the outbreak of war he had secured a commission, and had served until the Armistice without distinction but with satisfaction to himself and his superior officers.

Meanwhile his father had died, leaving far less than his only child had confidently expected. And on demobilisation Harold had found himself possessed of a small income, of which he could not touch the capital, an instinctive dislike of the prospect of hard work, and a promising taste for dissipation. His problem was so to reconcile these three factors as to gain the greatest pleasure from existence. He solved it in his own fashion. There were reasons which drew him towards London, and particularly towards Paddington. By a curious chance he saw the notice ‘Rooms to Let’ painted in sprawling letters on a board propped up in Mr Boost’s front garden. The idea tickled him; he could live here in such seclusion as he pleased, spending the minimum on rent and thereby reserving the maximum for pleasure. To this unpromising retreat he moved so much of his father’s furniture as the place would hold, the remainder he sold. His orbit in future was bounded by the Naxos Club on the one hand and Riverside Gardens on the other.

But sometimes, deviating slightly from this appointed path, as a comet surprises astronomers by its aberrations, he touched other planes of existence. Revelling in the content of idleness as he did, he yet felt at long intervals that irresistible itch which impels the hand towards pen and paper. The eventual result was a novel, which, with engaging candour, he himself described as tripe. Tripe indeed it was, but tripe which by the method of its preparation had acquired a pronounced gamy flavour. It dealt with the lives and loves of the peculiar stratum of society which frequented the Naxos Club. To cut a long story short, Aspasia’s Adventures was accepted by a firm of publishers who, as the result of persistent effort, had acquired an honourable reputation for the production of this type of fiction. With certain necessary emendation, the substitution of innuendo for bald description, it was published, and brought its author a small sum in royalties, a few indignant references in the more hypocritical section of the Press, and an intimation from the publishers that they would be prepared to consider further works of a similar nature. But it brought more than this. It brought the means of quieting the last scruples of an almost anæsthetised conscience. Harold Merefield’s method of life was crowned by the justification of a Career.

But it was not of his career that Harold was thinking as he lay in his comfortable chair. In fact, he found it difficult to think consecutively about anything at all. He knew that he was tired and sleepy, but the act of closing his eyes produced an unpleasant and nauseating sensation, in some way connected with rapidly-revolving wheels of fire. It wasn’t so bad if he kept them open. Certainly the flame of the candle refused to be focussed, and advanced and receded in the most irritating fashion. A wave of self-pity flowed over him. He was a wretched, lonely creature. Vere had forsaken him, Vere, the girl he had given such a good time to all these months. Vere’s form kept getting between him and the candle, tantalising, mocking him. Somewhere, in the dark corners of the room, another female form hovered, a reproach, a menace to his peace of mind. He laughed scornfully. Oh yes, it was all very well for April and her father to upbraid him as a rotter, to fling the authorship of Aspasia in his teeth. Why couldn’t they say straight out that Evan Denbigh was a more desirable match for April? Damned young prig! He hadn’t the guts of a louse.

For a moment his fluttering thoughts lit upon the person of Evan Denbigh. His sweeping condemnation was followed by a wave of generosity. Good fellow, Denbigh, at heart, but not at all his sort. Hardworking, clever fellow, and all that. Of course, April would prefer him to a miserable lonely devil like himself. Let her marry him; he would take his revenge by showing them what he could do. He could write a best-seller if he put his mind to it. Yes, by Jove, he’d start now.