Полная версия

Amazing Philanthropists: B1

Cover

Title Page

Introduction

The Grading Scheme

Alfred Nobel

Andrew Carnegie

John D. Rockefeller

Thomas Barnardo

Henry Wellcome

Madam C. J. Walker

Glossary

Keep Reading

Copyright

About the Publisher

Collins Amazing People Readers are collections of short stories. Each book presents the life story of five or six people whose lives and achievements have made a difference to our world today. The stories are carefully graded to ensure that you, the reader, will both enjoy and benefit from your reading experience.

You can choose to enjoy the book from start to finish or to dip into your favourite story straight away. Each story is entirely independent.

After every story a short timeline brings together the most important events in each person’s life into one short report. The timeline is a useful tool for revision purposes.

Words which are above the required reading level are underlined the first time they appear in each story. All underlined words are defined in the glossary at the back of the book. Levels 1 and 2 take their definitions from the Collins COBUILD Essential English Dictionary and levels 3 and 4 from the Collins COBUILD Advanced English Dictionary.

To support both teachers and learners, additional materials are available online at www.collinselt.com/readers.

The Amazing People Club®

Collins Amazing People Readers are adaptations of original texts published by The Amazing People Club. The Amazing People Club is an educational publishing house. It was founded in 2006 by educational psychologist and management leader Dr Charles Margerison and publishes books, eBooks, audio books, iBooks and video content, which bring readers ‘face to face’ with many of the world’s most inspiring and influential characters from the fields of art, science, music, politics, medicine and business.

The Collins COBUILD Grading Scheme has been created using the most up-to-date language usage information available today. Each level is guided by a brand new comprehensive grammar and vocabulary framework, ensuring that the series will perfectly match readers’ abilities.

CEF band Pages Word count Headwords Level 1 elementary A2 64 5,000–8,000 approx. 700 Level 2 pre-intermediate A2–B1 80 8,000–11,000 approx. 900 Level 3 intermediate B1 96 11,000–15,000 approx. 1,100 Level 4 upper intermediate B2 112 15,000–19,000 approx. 1,700For more information on the Collins COBUILD Grading Scheme, including a full list of the grammar structures found at each level, go to www.collinselt.com/readers/gradingscheme.

Also available online: Make sure that you are reading at the right level by checking your level on our website (www.collinselt.com/readers/levelcheck).

Alfred Nobel

1833–1896

the man who created the Nobel Prize

I was a chemist and a businessman. My greatest invention was dynamite, and I made a large fortune from selling it around the world. Then, one day in Paris, five words changed my life forever.

Although I was Swedish and was born in Stockholm, I grew up in St Petersburg in Russia. I arrived in the world in 1833, at a bad time for my family. My father had problems with his business and in the year that I was born, he lost all his money. He had a wife and three sons and he decided to start again in a new country. First he started a business in Finland, and then, when I was five, he moved to St Petersburg, leaving us behind in Stockholm.

My father was a great inventor, as well as a businessman. In northern Europe in those days, a lot of things were made out of wood. He invented clever new tools for making things out of wood, and created a successful business in his new Russian home. When I was nine years old, we were able to join him. My mother was very pleased that the family was back together, especially as she was going to have another baby. My brother, Emil, was born that year.

My father’s company was called Nobel & Sons. It grew into a large engineering company, making all kinds of machines, from steam engines to early central heating. The Industrial Revolution was happening in Europe at this time. Machines could now make most things that humans had made by hand for centuries.

We lived in a comfortable wooden house in St Petersburg, but we were not rich. My brothers and I were educated at home by private teachers. We studied history, science and literature. As well as Swedish, which we spoke at home, we learnt to speak Russian, French, German and English. This helped me a lot later on when I set up companies around the world.

One of my favourite subjects was literature. I especially admired the English poet Shelley, with his love of humanity and peace, and his exciting political ideas. I wrote poems myself, but I was never satisfied with them and I always burned them. I shared my father’s love of chemistry, and together we tried out new ideas. He also taught me how to be a good businessman.

When I was 17, in 1850, I left home to see some of the world. I spent a year in Paris, working with a famous French chemist. Then I went to the USA, where I studied the latest technology. Although I didn’t go to university, I received an excellent education watching some of the world’s best scientists. The long journey home to Europe across the Atlantic gave me time to think about my future. What kind of business should I try? Over the last year I had become interested in explosives, which were very basic at that time.

My family was back in Sweden by now, and I joined them there. In 1863, I successfully created a new kind of explosive, using the chemical nitroglycerin, a kind of explosive liquid. Nobel & Sons was now based in Heleneborg in Sweden, where they tested new chemical recipes.

But one terrible day, an experiment went wrong. A huge explosion at the factory killed my younger brother Emil, and several of the company workers. It was a very sad day for the family, and we had a big decision to make. Should we sell the business and stop making explosives?

We decided to continue, but I moved away from Heleneborg. I set up my own factory near Hamburg in Germany, calling it Alfred Nobel & Company. There was more bad luck, however. An enormous explosion destroyed the factory, and many of my workers were injured.

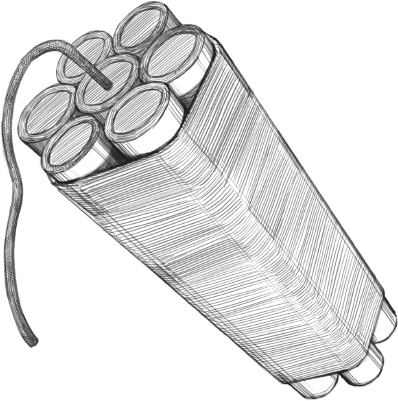

The explosives were not stable. I had to change the recipe. Nitroglycerin is very difficult to work with, and this had caused the explosions. In one experiment I added a new ingredient. The new mixture was still dangerous, but it was more stable than before. I called it ‘dynamite’.

In the next few years I started new companies in the USA and Britain, making dynamite. I first showed my new product to the world in England. I set fire to sticks of dynamite and threw packets of dynamite off a cliff. The English decision-makers did not believe my new product was safe, however. Unfortunately, there was a big explosion near Liverpool in July 1869 caused by containers of nitroglycerin. After that, companies could not use or sell nitroglycerin, or move it from one place to another in England.

I could not get permission to open a dynamite factory in England. So I went to Scotland, where some businessmen helped me to set up The British Dynamite Company in April 1871, on the west coast. The factory was at Ardeer, about 30 kilometres south of Glasgow.

Although I now had many businesses to run, I continued to make new explosives. I created a more powerful explosive called ‘gelignite’, beginning to sell it in 1876. Gelignite had lots of uses and it quickly became very popular. It was perfect for industries needing small explosions. You could use it to break up rock. Governments realized that it would be very useful during a war.

Business was good. We had more and more orders for dynamite, and it was difficult to make enough. I was making a lot of money, and in 1873, I bought a large house with big gardens in Paris. I employed a secretary there called Bertha Kinsky. I fell in love with Bertha, who was ten years younger than me. Unfortunately for me, she was already engaged to be married to a man called Baron Arthur von Suttner. After they married, I only met her again twice, but we often wrote to each other. She worked hard for world peace and she gave me a lot of advice in later years.

I was now making a fortune from sales of dynamite and gelignite around the world. I spent most of my time managing my many businesses, and life was good.

Then, one day in Paris in 1888, I had the biggest shock of my life. I picked up a newspaper and saw a headline: ‘The man who sells death is dead.’ I read the rest of the announcement. ‘Dr Alfred Nobel,’ it said, ‘has died. He became rich by finding ways to kill more people faster than ever before.’

Of course, I was not dead. In fact, my older brother Ludvig had died, and the newspaper had thought it was me. But it was not the mistake that shocked me. It was not Ludvig’s death that shocked me. It was those five words that shocked me. I was ‘the man who sells death’. In the world’s eyes, I was a killer. I was 55 years old. I asked myself many questions. What was the purpose of my life? Did I support war or peace? What should I do with my great fortune?

Those five words – ‘the man who sells death’ – changed my life forever. It took me seven years to decide what to do. During that time, I moved to San Remo in Italy, my final home. On 27th November 1895, at the Swedish-Norwegian Club in Paris, I announced my decision. I put 31 million Swedish kronor (today, worth about US$265 million) into a special bank account. The money was for prizes for work that helped humanity.

The Nobel Prize medal

I chose five prizes – for Physics, Chemistry, Medicine, Literature and Peace – to be given each year. I called them the Nobel Prizes. The prize winners could be any nationality, race or religion. Each prize was a large amount of money so that the winner could continue his or her work.

Of course, the money came from dynamite, and dynamite could be used for peace or war. People could use it to help their communities, but also to kill each other. I could not change the past, however. Now I wanted to help the world to build a better future.

The first Nobel Prizes were awarded in 1901. But I did not live to see that day. I died on 10th December 1896, at my home in San Remo in Italy. I was 63 years old.

The Life of Alfred Nobel

1833 Alfred Bernhard Nobel was born in Stockholm, Sweden, the third son of Immanuel and Andriette Nobel. Alfred’s father, Immanuel Nobel, lost all his money. He tried to start a new company in Finland. 1838 Immanuel moved again, this time to St Petersburg in Russia, where he set up an engineering company. 1842 When Alfred was nine, he moved with his mother Andriette and two older brothers to join his father in St Petersburg in Russia. He was taught at home with his brothers, and became interested in chemistry. 1850 Alfred spent a year in Paris, working with the French chemist Professor Jules Pelouze. He also travelled in Italy and the USA, where he saw the latest technological inventions. 1862 Alfred returned from the USA and joined the family firm in Sweden, starting to experiment with nitroglycerin. 1863 He began to sell his new explosives. The Nobel family set up a new business at Heleneborg in Sweden, where they tested new chemical mixtures. 1864 Alfred’s younger brother, Emil, was killed in an explosion, together with company workers. The family continued the business, while Alfred decided to set up his own company. He called it Nitroglycerin AB. 1865 He moved to Germany and set up the Alfred Nobel & Company factory near Hamburg. An enormous explosion destroyed his factory. He made a more stable explosive, which he named ‘dynamite’. 1866 He took his business to other countries, opening the United States Blasting Oil Company. 1871 He started a new business called the British Dynamite Company (later known as Nobel’s Explosives Company) at Ardeer in Scotland. 1873 Alfred moved to Paris, where he bought a large house and gardens, and set up another dynamite factory. 1876 He created a more powerful explosive called ‘gelignite’ which sold very well. 1876 He employed Bertha Kinsky von Chinic und Tettau as a secretary. He fell in love with her, but she returned to Vienna after a short time. 1879 He discovered that Bertha was engaged to be married to a man called Baron Arthur von Suttner. Arthur and Bertha married. Alfred and Bertha wrote letters to each other all their lives, and Alfred always listened to Bertha’s ideas on world peace. 1880 He joined his Swiss and Italian companies into one, and he continued to make a lot of money. 1885 He formed a group of German explosives companies. 1888 He saw a report of his own death in a Paris newspaper. It described him as ‘the man who sells death’. He saw himself through the world’s eyes and spent the next seven years thinking about his life. 1891 Alfred moved to San Remo, Italy. 1895 He announced his decision at the Swedish-Norwegian Club in Paris. His plan was to use most of his fortune to create five Nobel Prizes. The money still pays for the five prizes today, which are given for the best work in Physics, Chemistry, Medicine, Literature and Peace. 1896 Before the award of the first Nobel Prize, Alfred Nobel died aged 63. 1901 The first Nobel Prizes were awarded. They are still given every year to men and women for excellent work.Andrew Carnegie

1835–1919

the businessman who built libraries for poor people

In 1901, I became the richest man in the world. I had made my money from iron and steel. I did not want to be the world’s richest man when I died, however. So I decided to give all my money away.

My story is about a poor boy who became a very rich man. I was born on 25th November 1835 in Scotland. My parents both came from working families who earned a living with their hands. My mother’s family were leather workers. My father made linen by hand. We lived in Dunfermline, a small Scottish town near Edinburgh, and life was not easy. My father had to work hard to earn enough money to buy food for us. He was angry that life was so difficult for working people and he joined a group called the ‘Chartists’. The Chartists were working men who wanted a better future.

At that time, only rich men were able to vote or become Members of Parliament. The Chartists believed that all men should have a vote. They were also worried about safety at work. The Industrial Revolution was happening all across Europe at this time, and people were inventing bigger and better factory machines. Because the machines were new, however, they caused many accidents. The Chartists wanted factory owners to take better care of their workers. Many people in government believed that the Chartists were dangerous revolutionaries.

Our house was a noisy house. My father and my Uncle Tom were always discussing politics. Uncle Tom did not like the queen or the church. My Uncle George loved Scotland, and often performed the poems of Robert Burns, Scotland’s most famous poet. I learned an important lesson from these noisy men. If you want to change things, you must have power. And to get power, you must have money.

I had to leave school when I was only 11, so my education was short. I started learning my father’s trade. But some days there was no work, and the pay was terrible. Things got worse because factories were using machines to make cheap linen. Their linen was much cheaper than our linen which was made by hand.

The year 1848 was a year of revolutions in Europe. The German philosopher Karl Marx wrote The Communist Manifesto, and workers in many countries wanted to improve their lives. It was a year of change for our family too.

My father came home one day and said that there was no more work. He said we had no choice – we must emigrate to the USA. Two of my mother’s sisters had already moved there. We sold our furniture, packed our few things and set off on a great adventure.

The journey across the Atlantic was wonderful and terrible. I was 13 and very excited. But the sea was very rough and many of the passengers were sick. We had very little space or fresh air and the journey took 50 days. But we were the lucky ones. There were often fires on ships when they crossed the Atlantic in those days, and many people died at sea. We arrived in America on 5th July, and continued by train to Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania, where my aunts lived.

My father and I found work in a clothes factory, and we lived in a small house that one of my aunts owned. I wasn’t able to go to school, so I had to teach myself in the evenings. We lived near a man with a large personal library, who allowed people to borrow his books. I always remembered his kindness.

I worked all day in the factory. The pay was terrible, and I only earned $1.20 a week. Then I had some good luck. The Ohio Telegraph Company was advertising for young men to carry messages. In those days before the internet or even telephones, messages were sent by telegraph. I got the job and was very happy. Instead of spending all day in a dark and dirty factory, I could now enjoy being in the sun and fresh air. The pay was much better too. Suddenly I was earning $5 a week. I was on my way to a better life.

There was another advantage too. Taking messages to the theatre was one of my regular jobs and I was allowed to stay and watch the plays. Often they performed Shakespeare which was an amazing experience for a young boy like me.

For three years I worked at the Telegraph Company. I learned to use the telegraph machine, and soon I was sending and receiving messages. I was a quick and happy worker. Then I got a new job as secretary to Thomas A. Scott of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company. Mr Scott became like a second father to me. He helped me to make investments and even lent me $600 to invest in another railway company, Adams Express. When my first dividend for $10 arrived in the post, I was very excited. My business career had started.

But 1856 was also a very sad year in our family, because my father died.

I made more investments, taking Mr Scott’s advice. I borrowed money from the bank and invested in railways and railway bridges.

And then the American Civil War started. In 1861, the North (called the ‘Union’) and the South (called the ‘Confederacy’) of America went to war over slavery. Mr Scott and I were sent to Washington to help the Union Army. We set up a telegraph service, and we organized the Army’s transport system. I was injured when I was cutting Confederate telegraph lines.

I was given three months off work in 1862, and I decided to visit Dunfermline with my mother. I had forgotten how beautiful Scotland was and how much I loved our country.