Полная версия

Amazing Mathematicians: A2-B1

Cover

Title Page

Introduction

The Grading Scheme

Galileo

René Descartes

Isaac Newton

Carl Friedrich Gauss

Charles Babbage

Ada Lovelace

Keep Reading

Glossary

Copyright

About the Publisher

Collins Amazing People Readers are collections of short stories. Each book presents the life story of five or six people whose lives and achievements have made a difference to our world today. The stories are carefully graded to ensure that you, the reader, will both enjoy and benefit from your reading experience.

You can choose to enjoy the book from start to finish or to dip into your favourite story straight away. Each story is entirely independent.

After every story a short timeline brings together the most important events in each person’s life into one short report. The timeline is a useful tool for revision purposes.

Words which are above the required reading level are underlined the first time they appear in each story. All underlined words are defined in the glossary at the back of the book. Levels 1 and 2 take their definitions from the Collins COBUILD Essential English Dictionary and levels 3 and 4 from the Collins COBUILD Advanced English Dictionary.

To support both teachers and learners, additional materials are available online at www.collinselt.com/readers.

The Amazing People Club®

Collins Amazing People Readers are adaptations of original texts published by The Amazing People Club. The Amazing People Club is an educational publishing house. It was founded in 2006 by educational psychologist and management leader Dr Charles Margerison and publishes books, eBooks, audio books, iBooks and video content, which bring readers ‘face to face’ with many of the world’s most inspiring and influential characters from the fields of art, science, music, politics, medicine and business.

The Collins COBUILD Grading Scheme has been created using the most up-to-date language usage information available today. Each level is guided by a brand new comprehensive grammar and vocabulary framework, ensuring that the series will perfectly match readers’ abilities.

CEF band Pages Word count Headwords Level 1 elementary A2 64 5,000–8,000 approx. 700 Level 2 pre-intermediate A2–B1 80 8,000–11,000 approx. 900 Level 3 intermediate B1 96 11,000–15,000 approx. 1,100 Level 4 upper intermediate B2 112 15,000–19,000 approx. 1,700For more information on the Collins COBUILD Grading Scheme, including a full list of the grammar structures found at each level, go to www.collinselt.com/readers/gradingscheme.

Also available online: Make sure that you are reading at the right level by checking your level on our website (www.collinselt.com/readers/levelcheck).

Galileo

1564–1642

the man who believed the Earth went around the Sun

I believed that the Earth orbited the Sun. People were afraid of my theories at the time and called me a heretic. But now they call me ‘The Father of Modern Science’.

I was born in Pisa, Italy, in 1564. I was the oldest of six children, but unfortunately, only three of us survived childhood. My father, Vincenzo Galilei, was a well-known musician and he called me Galileo. When I was 8 years old, my family moved to Florence. But they left me behind in Pisa, in the care of a relative. In 1574, I joined my family. When I was 11 years old, I was sent to the Camaldoese Monastery school in the town of Vallombrosa, just outside Florence.

My father wanted me to be a doctor. So, after I finished school, I went on to study medicine at the University of Pisa. However, I soon decided that medicine was not the right career for me. I was much more interested in mathematics, physics and the arts. So I spoke to my father and he let me change my course to mathematics and natural philosophy.

One day, while I was at the university, I noticed something interesting. I was looking up at the ceiling and watching a lamp swinging – or moving from side to side. The length of the lamp’s swing from side to side changed with the wind coming through the open window. I noticed that the lamp always took the same number of seconds to complete its swing from one side to the other.

When I returned home, I set up two pendulums and carried out some experiments. Soon I realized that I had discovered a truth – that all things swing at the same speed. This was later called ‘the law of the pendulum’ and it was used to make clocks.

I left university in 1585 without a degree and began working as a teacher in mathematics. I also taught drawing to students at the Academy of the Arts of Drawing in Florence. By now, I loved ‘the beauty of numbers’. I was also very interested in how the weight of an object could be measured using a balance. I created a thermoscope – an instrument which shows changes in temperature. This was later developed into the thermometer, which measured changes in temperature. In 1586, I wrote my first book. It described the design for a ‘hydrostatic balance’ – a device which weighed objects using air and water. I called the book The Little Balance.

Life was going well for me. But I wasn’t earning a lot of money from private teaching. I needed to get a university job that paid a good salary. So I applied for teaching jobs at Sienna, Padua and Bologna universities. But I wasn’t successful – probably because I didn’t have a degree. Then, in 1589, I was offered the job of Chair of Mathematics at the University of Pisa.

At Pisa, I began to doubt Aristotle’s theories about objects which fall. Aristotle – a Greek philosopher – believed that the weight of an object decided its speed when it fell. So I decided to carry out a simple experiment. I climbed to the top of the Leaning Tower of Pisa and I dropped balls of different weights to the ground. The balls were of different weights, but the same size. They all hit the ground at the same time. After this, I wrote my book called On Motion. In it, I said that the speed of objects which fall depends on their shape and size, not on their weight as Aristotle said. In the future, I said, a theory had to be tested before it was accepted.

In 1591, my father died. I had to look after my brothers and sisters because I was the oldest child. This meant I needed to find work which paid a better salary. So from 1592 until 1610, I was Professor of Mathematics at Padua University. The job allowed me to teach, think and do many experiments.

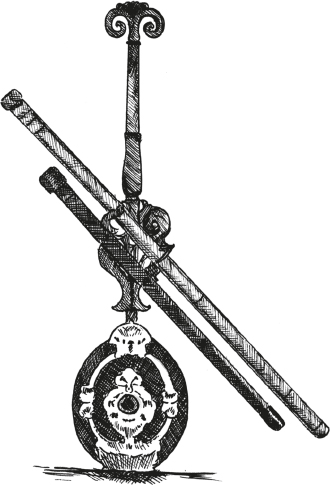

Galileo’s telescope

During my time at Padua, I invented a water pump. I also invented a military compass – a device used by the army to plan battles. In 1609, the Italian scientist Paolo Sarpi wrote to me. He told me about a new invention in Holland called a ‘telescope’. It was a device which magnified things – it made them look much bigger. The telescope allowed astronomers to look much more closely at the stars and planets in the sky. In a short time, I had developed its design. I called my telescope, ‘Perspicullum’. Perspicullum could make the planets look eight times bigger than their normal size.

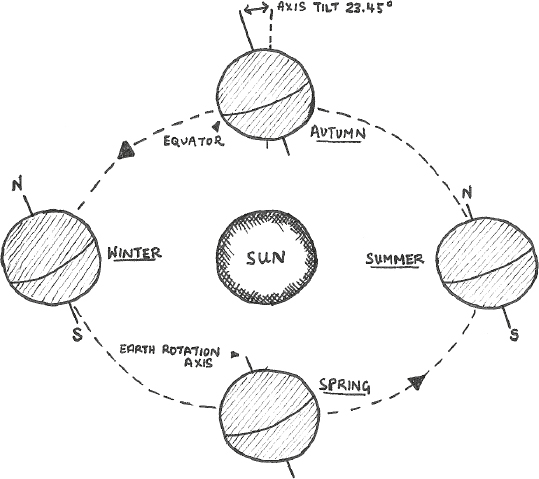

In 1610, I wrote a book called Starry Messenger about the discoveries that I’d made with my telescope. It described the mountains of the moon, as well as Jupiter’s brightest four moons. In that same year, I also discovered the ‘Phases of Venus’ – the changes of Venus’s light caused by the Sun. As I continued to use Perspicullum to study the planets, I began to ask questions about an important religious belief. In the 17th century, everyone believed the Earth was the centre of the universe. People thought that the planets and the Sun orbited around us. But my telescope showed me that the Earth and other planets orbited the Sun.

Galileo believed that the Earth orbited the Sun

In 1611, I became Chief Mathematician at the University of Pisa. There, I wrote my Discourse on Floating Bodies and Letters on Sunspots. I also described my theories about the Earth and Sun to the Grand Duchess Christina of Tuscany. The letter was sent to Christina in 1615 but not published until 1636. When they read my letter, the priests of the Catholic Church in Rome became very angry. I agreed with the beliefs of the great mathematician and astronomer, Copernicus. Like Copernicus, I was asking questions about the belief that the Earth was the centre of the universe and not just a small part of it. My theories soon brought me terrible trouble.

In 1632, I published my book Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems. It had taken me six years to write it. But the book was banned by the pope as soon as it was published. All my other writings were banned, too. At first, I was charged with heresy and sentenced to death. Later this sentence was changed to house arrest.

I spent the rest of my life locked in my house. But I continued with my writing and experiments. In 1638, I wrote another book called Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Concerning Two Sciences. It was about my work in physics and my studies on gravitation. The book was banned in Italy but published later in Holland.

By now, I was getting old and I was often sick and in great pain. But I wasn’t allowed to see doctors or take medicine. In 1636, I started to lose my eyesight. By the following year, I’d gone blind and I could not hear well. But my mind continued to work and my student, Vincenzo Viviani, became my eyes and ears. He carried out experiments for me and wrote down the results. In 1642, I died at my house in Arcetri, near Florence. I was 77 years old. I was kept under house arrest until the day I died.

The Life of Galileo Galilei

1564 Galileo Galilei was born in Pisa, Italy. He was the oldest of six children. 1572 When he was 8 years old, Galileo’s family moved to Florence. However, Galileo stayed in Pisa, in the care of a relative. 1574 Galileo joined his family in Florence. 1575 Galileo attended the Camaldolese Monastery, at Vallombrosa, near Florence. 1581 He began studying medicine at the University of Pisa. He then changed his course to mathematics and philosophy. 1585 Galileo left Pisa University without a degree and worked as a teacher of mathematics. 1586 He published his book The Little Balance. 1588 He worked as a teacher at the Academy of the Arts of Drawing in Florence. 1589 Galileo became Professor of Mathematics at the University of Pisa. 1590 He wrote his book On Motion. 1591 His father died and Galileo had to look after his brothers and sisters. 1592–1610 Galileo was Professor of Mathematics at the University of Padua. 1595 He invented a compass. 1600 His book Mechanics was written. 1609 He improved the design of the telescope and called it ‘Perspicullum’. 1610 Galileo published Starry Messenger. He looked at the mountains of the moon as well as Jupiter’s brightest four moons. He discovered The Phases of Venus. 1611 He became Chief Mathematician at Padua University. 1612 Galileo wrote Discourse on Floating Bodies. 1613 He wrote Letters on Sunspots. 1615 His Letter to Grand Duchess Christina was written. However, it was not published until 1636. 1616 The Catholic Church became angry with his ideas. They warned him about his Copernican beliefs and banned his writings. Galileo wrote Discourse on the TidesКонец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.