Полная версия

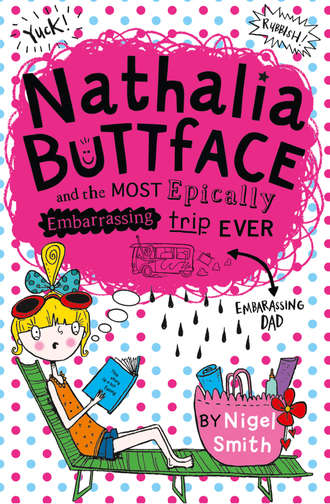

Nathalia Buttface and the Most Epically Embarrassing Trip Ever

“He’s not,” said the drummer, who used to be called Simon but apparently was now known as Dirty McNasty. “Oswald’s our security.” Oswald cracked his knuckles. Nat thought that he was probably there to stop the audience leaving.

“Oswald AND little Darius,” said Mr McNasty. “You’re coming wiv us too, ain’t ya?” he said. “We all have a lot of – love – for little Darius.” He cuffed Darius round the head lovingly enough to make his eyes wobble.

“Don’t go asking for no autographs,” said the singer, Derek Vomit, to Nat, unnecessarily. “You don’t get no autographs, unless you get a tattoo of us. Shows you’re a real fan. We’re giving Darius one when we get to Oslo.”

“Listen to this,” said Dad, coming back in, holding a tiny, pink ukulele. It looked like a guitar that hadn’t grown up yet. Nat felt sick. “I wrote this song ages ago. It was very popular down the student union bar. I was quite the rocker.”

Nat wanted to hide under a cushion but it was unpleasant enough sitting ON a Bagley cushion; you would not want to be under one.

“Feel free to join in on the chorus, lads,” said Dad, plunking tunelessly away. He LOVED meeting fellow musicians. “You’ll probably want to use it at one of your gigs.”

Nat knew there was only one thing worse than Dad playing the ukulele. It was Dad singing. Dad started singing.

“I am a rocker,” he started, surprisingly loudly. And unsurprisingly flat. “I am a shocker. You be the door and I’ll be the knocker …”

Oswald and the Filthy Grannies stared at the warbling idiot, grinning. Nat immediately saw they were nasty grins, but Dad took it for encouragement and sang louder.

“Let’s have a go,” said the guitarist, whose mum knew him as Jason but who was now called Stinky Gibbon. Dad handed him the uke. Stinky played a couple of notes and there was a crunching noise as he deliberately broke the neck off. “Oops, sorry!” he said, laughing. He handed Dad the smashed instrument back. “That’s rock and roll for you.”

Dad took the mashed instrument and thought for a moment.

“You’re taking Darius with you this summer, are you?” he said to Oswald. There was a bit of steel in Dad’s voice that Nat hardly recognised. Oswald nodded.

“Well, you’re not,” said Dad. “He’s coming with us.”

Nat couldn’t be sure, but she thought that under his horrible black beard, Oswald Bagley smiled.

Dad wasn’t wearing a baseball cap; he thought baseball caps looked stupid. He was wearing an old T-shirt with ‘Little Monkeys’ written on it. Underneath was printed a photo of Nat, aged four, holding a monkey in a safari park. Nat was pulling a face because the chimp had just poked her in the eye. Dad thought the picture was cute, hence the T-shirt. Nat did not think it was cute, hence she’d thrown it in the bin fourteen times. But it still kept appearing. Next time, she thought darkly, I’m setting fire to it. Even if Dad’s wearing it.

But even worse than the T-shirt were Dad’s shorts. Dad wore shorts from June 1st to August 31st, because, he said, that was summer. He didn’t wear them at any other time, no matter how hot, and he never wore anything else in the summer, no matter how cold or rainy. Dad was very proud of his shorts because he’d had them AT SCHOOL and he could still get into them. They were red and shiny and very very short. Way too short. From a distance it looked like he’d just forgotten to put his trousers on. Old ladies walked past the drive tutting and shielding their eyes.

Dad had extremely thin white hairy legs and in these shorts you could see ALL of those thin white hairy legs, from ankle to unmentionable. He bent over in the van and made it worse. Nat heard shrieks from the other side of the street and had to hide behind the Dog.

To top it all, Dad had the radio on. Fighting over the radio was becoming what writers of modern classics would call: AN ISSUE. In the old days, Nat didn’t care what awful music Dad listened to, because she was still finding out what music she liked. But now she was older and had found out what she liked and it was the music they played on RADIO ZINGG!!! It was happy bouncy music you could dance to. Dad liked RADIO DAD. The songs on RADIO DAD went on for hours and if you tried to dance to them you’d break your legs. They were boring and miserable and now it was playing at full blast and all the neighbours would think that she liked Dave Spong and his Incredible Flaming Earwigs, or whoever it was.

Because of all this, Nat was very keen to get the van cleared and packed so they could get out of there. But the more Dad chucked out on to the drive, the more there was still inside. It was like some evil van curse.

Normal families fly abroad on holiday, thought Nat sourly, dragging more cases to the van. But Dad kept telling them it would be ‘more fun’ (in other words, cheaper) to drive there instead.

“We’ll need a car when we get there anyway,” he had argued to Mum. “And this saves us the expense of hiring one. Plus, we’ll make a holiday of the journey. We can sleep in the van. Or there’s a big old tent in the back. You like camping!”

This was not true. Mum hated camping. Mum liked hotels and hot water and fluffy towels and chocolates on the pillow and room service. She did not like:

Tents, campsites, bugs, sleeping bags, burnt sausages, shared showers, smelly loos, rain, fetching water from a pipe in a field, cows, hippies, wet socks, and any of the four great smells of camping – plastic, burnt wood, damp dirt and wee.

This wasn’t the reason she gave though. Mum would have to miss the whole camping bit because obviously, she said, she couldn’t get a month off work. “Unlike your father, who rarely gets a month ON work.”

Mum usually got upset when she missed out on family time, but Nat was pretty sure Mum was relieved to be missing out on the camping part of the trip.

Instead, the plan was that Dad, Nat and Darius would take the van over to France, and when Mum could get away she would fly out to join them, probably towards the end, and once Dad had found her a nice hotel nearby.

“But you can just stay in the house! I’ll have it done up by the time you arrive,” Dad had argued.

“Now, I don’t mean to be critical, love,” Mum had pointed out, “but you’re not a builder. You write jokes for Christmas crackers. I have no idea why you’ve agreed to do all this work. The last time you tried to put up a bookshelf you nailed your head to a copy of Great Expectations.”

Dad had mumbled something about it being a bit quiet on the Christmas cracker-joke-writing job front at the moment and that it might be good for him to develop another skill or two. Mum had just smiled and kissed him and reminded him to take out extra health insurance and a first-aid kit.

“Do you think we’ll need this?” Dad asked Nat, emerging backwards from the depths of the van, waving an electric pencil sharpener.

“No idea, Dad, I’ve got my eyes closed,” shouted Nat, burying her face in the Dog’s warm fur. “Please change your shorts.”

Whatever Dad said next was drowned out by the roar of a huge motorcycle engine. Oswald had arrived with Darius sitting on the back of the bike. The Dog bounded up, sure of a treat. Darius hopped off and picked some flies out of his teeth. He was carrying a small tatty rucksack. It didn’t look big enough to hold a decent packed lunch, let alone anything else.

“Is that all you’re bringing?” asked Nat.

“It’s all I’ve got,” Darius replied lightly, before getting bundled over by the excited Dog. The two of them rolled around in the front garden. Oswald nodded to Dad, revved his motorbike and sped off without saying goodbye to his little brother. Dad watched him go for a moment, then turned to Darius. “Best say goodbye to the mutt,” he said, “we’re taking him to the kennels later.”

Nat was shocked. “Dad—” she began.

“I know what you’re going to say,” he said, cutting her off, “but he’ll hate that long drive and he won’t like strange places and Mum’s too busy to look after him. He’ll be better off in a kennel, trust me. I’ve picked a nice one.”

Nat wasn’t one to take no for an answer. “Mum …” she shouted, running indoors.

Mum was on her mobile and doing emails at the same time. Nat wanted to tell her why she HAD to have the Dog with her and that Mum HAD to make Dad understand but didn’t want to interrupt so, after hovering nearby for a few minutes, she went upstairs and threw herself on the bed in misery.

Which is where she was when Bad News Nan came looking for her.

“Your fasher said you washn’t feeling very well,” she said, showering Nat with biscuit crumbs. Her voice was muffled due to the addition of digestives and the lack of teeth. Bad News Nan often kept her false teeth in her pocket so as not to wear them out by over-use. Many an evening at home had been livened up by the sudden discovery of Nan’s gnashers under a cushion.

Or in the dishwasher.

Or in the biscuit tin.

Or in the butter dish.

“It’s just Dad,” grumbled Nat, “and this stupid holiday. It’s going to be a typical Dad disaster, I know it. And if I haven’t got the Dog, there’ll be no one to have a sensible conversation with.”

Bad News Nan had stopped listening after the word ‘disaster’. She liked nothing better than a good disaster. “Well, if you think your life’s bad …” she began, and proceeded to tell Nat about:

Edna Pudding – lost two fingers in the bacon slicer at Morrison’s.

Deidre Scratchnsniff – put winning lottery ticket through a hot wash.

Frank Mealtime – took a pedalo out too far at Camber Sands and was captured by Somali pirates. His niece had to put all her bone china figurines on eBay to pay the ransom.

Nat wasn’t too sure how true any of these were (especially the Edna story, because the last time she’d seen Mrs Pudding she was working on the checkouts, not the deli counter), but funnily enough, they did make her feel a bit better.

“I’ve told your father this whole expedition is stupid,” she droned on. “I said little Nat should just come and stay with me this summer. Would you like that?”

Nat hesitated. On the one hand, Bad News Nan was completely mad and never stopped talking or eating unless she was asleep, and even then kept going sometimes. Nat knew she would be forced to listen to all the hard-luck stories that Nan collected the way Mum collected parking tickets. On the other hand, having no Dad to show her up sounded pretty amazing, and she could hang out with Penny Posnitch who lived round the corner from Nan. She could make a few new friends and maybe move up the popularity ladder at least TWO RUNGS.

And besides that, there would be NOTHING TO DO at Nan’s except do what Nan did – get up at lunchtime, watch endless episodes of Judge Judy, and never eat a vegetable again. On balance – it sounded brilliant.

Only one problem.

“How about Darius and the Dog?” Nat asked.

“I’m not looking after them,” said Nan firmly. “They’d both have to go in kennels.”

Nat sighed and reluctantly pushed herself off the bed. France it was. But she was NOT putting the Dog in kennels. She just needed a plan.

“Can I stay here and get a job in your office instead?” whispered Nat, only half joking.

Mum grinned. “Yes, I wish we could swap places. But look, you’re going to a foreign country with your idiot father and demon child Darius Bagley in a horrible van to rebuild a haunted house. Think how lucky you are!”

Sometimes, thought Nat, Mum’s sense of humour is as bad as Dad’s.

“Right, let’s go. Where’s the Dog?” said Dad, looking sweaty and harassed.

Somewhere in the Dog’s tiny doggie brain he must have sensed something was up, because they found him trembling under a pile of dirty washing. Dad had to carry him out to the van, still tangled up in the sheets and looking utterly pathetic. He turned his sad brown dog eyes to Mum as he was carried to the van, as if to say, “Are you doing this to me too?”

“In, in, let’s go,” said Dad to Nat and Darius as he slammed the door and started the engine. Or rather, tried to start the engine. It coughed and banged and wheezed and went silent.

Mum waved her arms, exasperated. “You said you’d get this horrible old thing ready for the road!” she said. “How do you expect it to carry you across half of France if you can’t get it off the drive?”

“We can’t go! We have to stay here, what a shame, never mind,” shouted Nat as she scrambled out of the van, her heart leaping with joy.

“Nothing I can’t fix,” said Dad, hopping out. He lifted the bonnet and leaned right over to get at the engine. There was a scream from Mrs Possett opposite at number 26 who wished she hadn’t chosen that moment to stand at the window and take her net curtains down.

“You could stop Dad going,” Nat said urgently to Mum, out of earshot, “he does what you tell him.”

“No, he doesn’t,” said Mum, pleased at the thought all the same, “but anyway, it’ll be good for him to fix this silly house and prove to everyone round here he’s not totally daft and useless.”

But he is, thought Nat.

There was muffled clanging and swearing from under the bonnet for about five minutes, until Darius jumped out of the van, holding some kind of multitool he’d taken from his rucksack. “Let’s have a look,” he said to Dad. “I’ve fixed Oswald’s bike loads of times.”

Dad slapped him on the back and walked over to Mum. “See,” he said, “no problem. Darius is going to mend it.”

“He’s just a little boy, you moron!” yelled Mum. “You ARE daft and useless.”

Told you, thought Nat.

By now there was quite a crowd gathering on the pavement to watch what was going on. The neighbours knew there was always something fun to watch at Nat’s house. A lot of them preferred it to the telly. Nat and the Dog got back in the van and hid.

“But he’s brilliant with his hands,” said Dad cheerfully. “Who do you think fixed our washing machine last month?”

In the van, Nat cringed. Even she knew Dad had just made a massive mistake. Mum grabbed the nearest object from the pile of junk that had been chucked out of the van. It happened to be a rude garden gnome that Dad once thought was funny. Now he just thought it looked heavy and sharp. She advanced on Dad dangerously. He smartly backed off, towards the small crowd, who were really getting their money’s worth today.

“You said you got an engineer out,” she said quietly. Nat got worried. Most people get louder as they get angrier, but not Mum. She started off loud, then got quieter. She was deadly quiet now.

“Be fair, love, he did a great job, and he was much cheaper than a real engineer. You can pay him in Mars bars and Pringles.”

Dad had also discovered that if you gave Darius enough fizzy orange pop he worked twice as quickly, but interestingly, Mum got even madder when he told her that.

Nat watched through her fingers as the rude gnome went whistling past Dad’s left ear and took out Mister Sponge who was peeping over the privet. He went down like a sack of bricks, but whatever he shouted was lost as the van roared to life, sounding louder and healthier than ever. Darius, face covered in oil, gave them a thumbs up and a huge smile from the driver’s seat.

“Darius, right, get out of that seat, shut the bonnet, get in the back, quick,” shouted Dad, slamming the door. “Bye, love, sorry, have to dash, love you, gotta catch the ferry, bye!” And they were off, scattering the neighbours as they went.

By the time they got to the kennels, the Dog had licked all the oil off Darius and Dad noticed he had a lot of texts from Mum on his mobile. He wouldn’t let Nat see them, but she did manage to glimpse a few of the words. One or two were completely new to her. She made a mental note to ask Darius about them when Dad wasn’t listening.

They were now in the leafy bit of town where the kennels were. It was the bit of town that pretended to be countryside, even though there was now a massive busy road going right through it, and a kebab shop and off-licence on almost every corner.

Soon they turned down a driveway with a big sign saying ‘Pawlty Towers’. Mournful howling resounded from behind large dark hedges. The woman who came to meet them at the front gate was middle-aged and built like a huge Saint Bernard dog. Nat sniggered when she said her name was Bernadette. The lady shot her a stern glance.

Bernadette wore a quilted green jacket and horse-riding trousers, even though Nat couldn’t see a horse anywhere. She took one look at Nat’s miserable dog – who was being carried out of the van, bundled up in the bed sheets like a pile of wet washing – and turned up her nose.

“Well, we usually only take pedigrees,” she said. “On the phone you said he was a pedigree.” Nat looked at Dad. Here we go again, she thought. Dad would say anything to try and get his own way.

“Did I?” he remarked innocently. “I think I said there was some pedigree IN him. Would you not call him a pedigree then?”

“No, this is what we in the dog business call a mutt,” said Bernadette. She was going to say a lot more but just then Dad hoisted the Dog higher and she suddenly got an eyeful of the shorts. “Oh my goodness,” she muttered. “Oh dear me.” She went red and quickly turned round. “Yes, well, there is one space. I’ll lead the way. DO NOT walk in front of me.”

As they trudged up the gravel path, past the cages full of dogs, all now barking like mad, Nat whispered to Darius: “Right, remember what we planned.” Darius looked blank. “The plan,” said Nat. “My plan to rescue the Dog. The plan I planned. It’s all planned. I told you the—”

“Nah, I’ve got a better plan, Buttface,” interrupted Darius, hopping over cracks in the pavement.

Nat fumed. “You have NOT got a plan!” she hissed. “You never have a plan. You just do the first thing that comes into your head. That’s why you get on with Dad. He’s the same. A big chimp, like you.”

She did an impression of Dad crossed with a monkey: “Oh look, a banana, think I’ll eat it. Oh no, now here’s a coconut, yum yum, ooh and now there’s a tyre, I’ll swing on that. Now, what was I doing with that banana? No idea, because I’m a chimp, ooh ooh.”

“Is that girl all right in the head?” said Bernadette. “Can you get her to stop making animal noises? She’s upsetting the dogs.”

“Just do the plan, chimpy,” said Nat. “MY plan.”

Nat’s plan was really complicated. She’d not had a lot of time to think about it. If she’d have had MORE time maybe she’d have made it simpler, but either way, this was Nat’s plan:

They get to the kennel door.

Darius pretends to have a terrible sudden illness, involving general agonised thrashing about and foaming at the mouth (Darius liked this bit).

While everyone’s looking after Darius, Nat steals the keys to the kennels.

Nat finds a dog that looks just like her dog, and frees it.

Nat gives Darius a secret signal to stop thrashing/foaming.

They give the lookalike dog to the kennel lady, who locks it up.

They hide Nat’s dog under the blanket and escape with him back to the car.

But when they got to the cage, Darius refused to pretend to be ill, no matter how hard Nat pinched him. The kennel lady unlocked the door. The Dog whimpered and jumped into Darius’s arms. Still Darius just stood there. Finally, in desperation, Nat threw herself on the ground and began shouting:

“Oh the pain, the pain. It’s at the very least rabies. Help.”

To her fury, everyone ignored her. Dad was filling out a form and Bernadette had already decided Nat was a silly little thing and best ignored. It was hopeless. Nat really DID feel like thrashing about, but in frustration. This is all Bagley’s fault, she thought. He’s ruined my perfect plan.

Then Darius did something strange. He threw the keys to the Atomic Dustbin on the path just behind Dad. “You’ve dropped the keys,” he said.

“Thanks,” said Dad, bending right over to pick them up. Bernadette made a strangled sort of being-sick noise and turned her back to them, sharpish.

At that moment, Darius shoved the Dog’s empty bed sheets into the cage and thrust the actual Dog at Nat, whispering: “Hide him.”

Inside the cage all you could see was the bundle of washing. As far as anyone could tell, the Dog could still have been wrapped up in it. He wasn’t, of course; because by now Nat was stuffing him under the table in the van and giving him one of Dad’s socks to chew quietly.

By the time Dad had straightened up again and Bernadette had opened her eyes, she had had quite enough of this weird family and quickly finished off the paperwork, locking the cage door without really looking and shooing them all off her property.

Nat was in the back of the van when Dad and Darius returned. “Sorry, love,” said Dad. “It’s for the best.”

Nat nodded. Under the table, covered in tea towels, was the Dog. He probably nodded too.

Nat didn’t speak to Darius again until it was dark and they were nearly at the ferry terminal. “Anyway, well done. My plan was better, though …” she finally muttered.

Darius didn’t say anything because he was trying to stretch a bogey longer than anyone had ever stretched a bogey before. The Dog didn’t say anything because he was rather hoping to eat the bogey.

“You just got lucky,” Nat went on. “Even my dad’s plans are better than yours and he’s a moron.”

At that moment Dad slammed on the handbrake. He turned round. “Probably should have thought of this before,” he said, with a sort of laugh, “but, um, you HAVE got your passport with you, haven’t you, Darius?”

Darius’s face was blank. His bogey snapped and slapped on the table.

“Told you so,” said Nat.