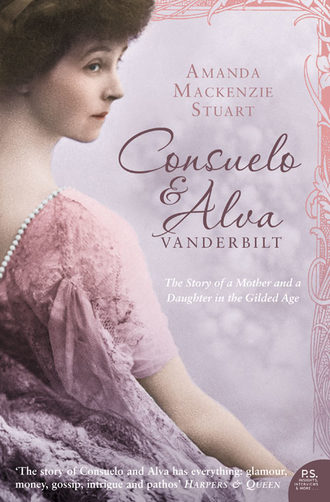

Consuelo and Alva Vanderbilt: The Story of a Mother and a Daughter in the ‘Gilded Age’

Полная версия

Consuelo and Alva Vanderbilt: The Story of a Mother and a Daughter in the ‘Gilded Age’

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента

Купить и скачать всю книгу