Полная версия

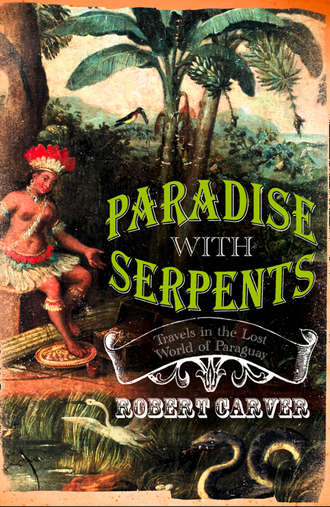

Paradise With Serpents: Travels in the Lost World of Paraguay

All around the town stood tight-buttocked young men with rags hanging out of their back pockets, beckoning energetically to passing cars to come their way. In some cities of the world these might have been taken to be gay hookers, trolling for trade: in Asunción they were parking touts. They owned or rented a couple of parking bays on the street, informally, that is, from the police or the local cacique. These they deftly waved drivers into with their rags, promising to look after the car while the owner was away, in return for a few guarani notes. It was the smallest possible of all small businesses. And all across the city there were furtive men, furtively pissing. They pissed beside parked cars, in the parks behind trees or in the rubbery shrubbery, against walls, in the sandy soil, down the blocked drains, against car wheels, anywhere. ‘¡No Pisar!’ read the signs impaled into the grass lawns outside the Pantheon of Heroes, but they pissed there too, in spite of the Honour guard in full-dress uniform with Mauser rifles and fixed bayonets. Pisar means ‘step’ in Spanish, not ‘piss’, so the signs really meant ‘don’t walk on the grass’, but the synchronicity was too great. The reason for this great, national incontinence was the compulsive, endless drinking of yerba maté, once known as Jesuit tea, by most of the adult male population. Made from the cut-up leaves of the ilex tree, to which hot water is added, maté is a mild narcotic and is widely drunk throughout the southern cone, nowhere more so than Paraguay, where the majority of the crop is grown and harvested. The bitter, dark green leaves are put in a pot, cup or more usually a gourd known as a maté: hot water is poured on and the drink sucked up through a metal straw known as a bombilla. For a cold brew, ice or just cold water is added to the leaf, and the drink is then known as tereré. The drinking of maté is a bonding ritual for Paraguayan men: one man will brew up, slurp up a draught, add more water, and pass the gourd round to his mate, as it were. Each man follows suit – slurp, add water, pass on. As TB and other saliva-conducted diseases are rife, this isn’t all that gets passed on, of course. Never mind, the macho Paraguayan male doesn’t: police on duty drink it, beggars drink it, civil servants, businessmen, politicians, shopkeepers, truck drivers – every Paraguayan male is constantly drinking the stuff all day long. You saw thermos flasks for sale everywhere, usually brightly coloured and made in China, essential for the brewing process. Men carried the complete gear around with them, thermos on shoulder strap, packet of leaf maté, spoon, gourd and bombilla. People didn’t go into cafés to drink it, they just made it up from their own kits wherever they happened to be – in offices or shops, on buses or in queues, squatting on the pavement or slumped in a park. The end result was a city full of men pissing all the time. In a shop selling religious icons I had noticed an almost life-size painted carving in wood of a Spanish friar, perhaps a Jesuit of yore, dressed in an old-fashioned ecclesiastical gown and a tonsure on his head. He had a straw in his mouth, and was sucking on what looked like a large, pear-shaped brown turd, but which in fact on closer inspection was a maté gourd. ‘The reason rioplatano men are so useless is all down to maté drinking,’ Alejandro Caradoc Evans told me one evening in the bar of the Gran Hotel, which was where he spent most of his waking hours. ‘They are all mother-dependent, not properly weaned, and addicted to the tit. The maté habit enables them to suck in public, and collectively, like babies in a crèche. Also, the stuff is a poison, slowly rots your brain and drives you mad. It is as bad as cocaine, but not so fast and more insidious. Notice how you almost never see the women drinking it, though they do behind closed doors in Buenos Aires, I have to say.’ Caradoc Evans was a Welsh Patagonian Argentinian, in his late twenties. He was cooling his heels in Asunción, rusticated for some unstated misdemeanour he had committed in Buenos Aires, where his family now lived. He had a complete contempt not just for Paraguay, but for the whole of South America. Like so many local critics, he had never actually left the continent, had never visited Europe, the place he dreamed of escaping to. He sat every day in the bar of the Gran Hotel, drinking beer and smoking cigarettes. He was allowed to run up a bar tab to a certain amount each day, and was allowed to eat in the hotel restaurant, but he had no cash. He was a prisoner of his family, under hotel arrest in Paraguay. He spoke perfect English and was dressed in a rather old-fashioned, officer-and-gentleman style, double-breasted blazer, club tie, light blue shirt, cavalry twill trousers and chelsea boots. He would not have looked out of place at a polo tournament somewhere near Cheltenham. His main aim, in so far as he had one, was to get a passport and go to Europe, and then never come back to South America again. ‘Except to be buried. I don’t mind them shipping my carcass home again. You may think this Third World dereliction is all very picturesque, but for those of us forced to live here it isn’t. Have you read V. S. Naipaul on the return of Eva Perón?’ I said I had. ‘Well, it’s a great pity he didn’t come to Paraguay, isn’t it? He could have out-Uganda’d his Uganda book here. This is the People’s Republic of the Congo of the South American continent, Stroessner as Mobutu. There is still slavery in the interior and the Indians are still being exterminated by ranchers and loggers, just as they were under good old Alfie.’ He spoke in fast, colloquial English most of the time, a language it was assumed most of the Guarani staff did not understand. ‘You know they found another thirty fantasmas, don’t you?’ Alejandro continued. I asked him what fantasmas were. ‘Well, when someone dies you don’t report it, you just go on drawing that person’s salary or pension – it means ghosts or phantoms. These thirty were army veterans, dating back to the Chaco War in the 1930s. God knows how long ago they died – decades, probably – still drawing their pay. One had a theoretical age of 120.’ Alejandro’s father had friends and business interests in Paraguay. ‘Powerful friends, who keep an eye on me,’ he added, with menace in his voice. ‘You never grow up in these rioplatano countries, you are always a child and kept as a child.’ It was evident that his clothes were expensive, but they were not well looked after and never seemed pressed. He looked rumpled and tousled as if he slept in his jacket and trousers. He was always well-shaved but often in need of a haircut. ‘Once I get my passport I’m off for good – you won’t see me for dust,’ he concluded with some vehemence, swigging back his beer for emphasis. I had met Argentine émigrés like Alejandro in London, where they complained ceaselessly to anyone who would listen of the cold, the damp, the expense, the lack of servants, the frigidity of the women, the unfriendliness of the men, the smallness of the apartments, and the terrible food. When they finally went back to Buenos Aires, I had heard, they fell into a pine for London that sometimes lasted a lifetime, endlessly reminiscing in the Jockey Club or the tearooms of Harrods in BA about their years in paradise, now lost. Someone had once seen a somewhat flashy tweed suit advertised in a Paris gent’s outfitters as ‘Très chic – presque cad’. No doubt whoever bought it was an Argentine anglomane.

Alejandro had been educated at an Argentine English-style Public School outside BA and his flawless English had cadences of the British upper classes of the 1950s. He said ‘crawse’ for ‘cross’, and his slang was dated, copied from the émigré masters, themselves products of the 1950s. This gave him the strange aura of being a contemporary of mine: he was young enough to be my son, almost my grandson – yet he spoke in much the way I had myself when I was about 12 or 13, before the 1960s really got going, and posh accents became a liability in swinging London.

‘What exactly are you going to do when you get to Europe?’ I asked him. I tried to imagine him among the pierced noses and glottal stops of the postmodern, multicultural, know-nothing estuary English.

‘Live,’ he replied with fervour. ‘It’s something you can’t do outside Europe. It is all pretend here, in case you haven’t noticed, pretend Europe, pretend USA. Everything that has been brought in from Europe has been misunderstood and misapplied. These ridiculous fake palazzi in the jungle put up by naked savages under the slave driver’s whip. I mean Solano López’s absurd fixation with Napoleon and imperial architecture – you know his grandfather, López’s I mean – was a mulatto bootblack on the streets of Asunción, of negro and Guayaki descent. He had no Spanish or Guarani blood, which is why he had no compunction in slaughtering all the Spanish and Guarani Paraguayans. The Guayaki and the Guarani loathed each other from pre-Spanish days. You see, a mestizo has to prove himself by doing down the white Creole – just look at Juan Perón. Francia, the first dictator here, was another mestizo. He forbade whites from marrying other whites, by law. Remember, this was the early 19th century when whites ruled the whole “civilized” world, and certainly the whole of South America. The mestizo on the rise, typically, joins the army, dons a colourful, picturesque uniform of a style obsolete in Europe by some decades, preaches uplift for the Indians and downfall for the white elite, makes a coup d’état, bankrupts the economy, ruins the country, persecutes and tortures everyone, declares war on the world, particularly the Catholic Church and the USA, and finally goes down in a welter of blood and chaos.

‘Francia avoided the latter because he was too paranoid and too mean to go to war. He just locked Paraguay in a prison for forty years instead – the anal retentive tyrant, the first truly modern totalitarian ruler, with secret police, torture chambers and the rest. Juan Perón in Argentina was the same type, a part-Indian whose mother was so dark she couldn’t be acknowledged in public. It’s part of the Argentine fantasy that there are no “natives” in the country, only aspirant Parisians and Londoners, though these are better dressed and sexier. In my grandfather’s day, among the English of BA, they always spoke of “Johnny Sunday”. Perón’s first names were Juan Domingo, and it wasn’t safe even to mention his proper name openly. When he was kicked out they found he had stolen US$500 million from the treasury alone. Solano López robbed the whole of Paraguay blind, stealing everything there was, including the jewels on the religious statues, replacing them with paste. Most of it got lost in his final retreat, but he did manage to transfer some of it out via Madame Lynch and the US and French consuls, through the Allied blockade, and so get it to Europe. His “heroic” death at Cêrro Corá was a mistake. He’d miscalculated. He was on his way to the Bolivian border and thought he was a full day ahead of his pursuers, which would have allowed him to get clean away. He would have ended up being fêted in Paris as a nationalist hero in exile, a sort of pre-Bokassa figure, complete with diamonds and crown.’

Alejandro lit another cigarette and motioned to the waiter for yet another beer. He had the most jaundiced view of Paraguay in particular and South America in general of anyone I had yet met in the country. In Europe, among expatriate South Americans, such views were more common; the exiles had left for a life abroad because they had such a low opinion of their homelands. It was interesting to listen to this abrasive and critical version of local history, to compare it with the bombastic nationalism of official Colorado propaganda which I got from other sources: you could always chose your national narrative in Paraguay.

‘Had Stroessner and Perón met?’ I asked.

‘Oh, yes – when Perón was overthrown Alfie was just starting out as a Junior-Jim dictator. He sent one of those smart, blackhulled fascist-era Italian gunboats that are moored opposite the palace down the river to BA to collect Perón, who’d taken refuge in the Paraguayan Embassy. Perón was well on his way down the usual mestizo war-against-the-world track when the air force had enough of him and bombed him out of his own palace. I think the navy were involved, too. He’d opened hostilities against the Catholic Church – like Francia did here – and was about to close the cathedral in BA and turn it into a workers’ playground. Every South American populist leader is potentially Tupac Amaru, the Inca noble who revolted against the Spanish in the 18th century. They want to bring down the house around them as they fall. Although they have absorbed all the French, Spanish and English customs, uniforms and ideologies, superficially at least, they remain spiritually Indian – that is, in revolt against the European way, while being besotted with the outward show of gringo style. It’s the latino paradox. They love us and hate us, and end up hating themselves for having absorbed so much of us. The Brazilian literary movement of the 1920s and 1930s called the antropofagos had a saying that they “ate a Frenchman for breakfast every day”. It was a reference to the Tupi-Guarani traditional cannibalism which the Europeans found so distressing when they arrived, on account of resurrection being made so complicated and difficult if people were eating each other all the time. I’ve never actually seen a direct prohibition on cannibalism in the Bible, mind you, have you? It’s kind of subsumed in the love-your-neighbour guff, I guess. There’s a strain in South American life that would like to undo the Conquest completely. It’s much the same in Africa, which South America resembles far more than most Europeans realize. Bokassa, Idi Amin and Mobutu could all have been South Americans, easily – the uniforms, the mania, the corruption, torture and confusion. The cross-cultural derangement is there, you see, on both sides of the Atlantic. King Lear with a colour chip and a culture chip, one on each shoulder.’

It was Alejandro who advised me to make a pilgrimage to see the British Ambassador. I asked him why. It seemed such a curious mission to undertake.

‘Because ambassadors have an unusually high profile in this country. Paraguay is right off the beaten track, the Gringo Trail, which you’ll have heard of, does not pass through here, as it’s too dangerous and not romantic enough, no native ruins and no McDonald’s. So few foreigners of note ever come here – de Gaulle was the first head of state ever to do so, by the way – that the foreigner is wildly overglamorized, and certain ambassadors act almost as vice-regents, deferred to by the governments which are always lacking in self-confidence and savoir-faire, not to mention credibility. In particular the ambassadors of the USA, Great Britain and France exercise great influence and add lustre to the shabby local political scene. These are countries important to Paraguay. The country was so nearly snuffed out by the War of the Triple Alliance, that Paraguayans do not trust either Argentinians or Brazilians. Good, cordial relations with these three most powerful states, who could stop any potential neighbour aggression, are very important here. You know that during the Falklands War, thousands of Paraguayans rang up the British Embassy offering to fight the Argentinians on the British side? What made it even richer was that the woman answering the Embassy switchboard was an Argentinian! ¡Ole! But seriously, if you ever found yourself in difficulties in Paraguay – and that is not hard to do at all – then knowing your Ambassador could prove very useful.’

But would the British Ambassador be in the slightest bit interested in seeing me, I queried. I couldn’t really imagine him wasting his time on such a trivial matter.

‘He’ll be delighted. You will probably be the first respectable Brit passing through for quite some time. Usually, the only ones who come here are on the run from Scotland Yard. He will be sitting twiddling his thumbs up there behind the armed compound, and you will be good for a whole morning of diplo-chitchat. He can put you in his monthly round-up to the FO – met and debriefed visiting British journalist and author Robert Carver who was en mission in Paraguay, a full and frank exchange of views ensued, etc. etc.’

I thought this was all highly unlikely, frankly, but I recognized good advice when I heard it.

‘Get the old bat on the reception desk here to ring up the Embassy and make an appointment for you. Your status will rise 500% immediately inside the hotel, for a start, and word of it will spread through Asunción, which is a small and gossipy town, in the end. You will become respectable, in a word.’

I expressed the doubt that anyone in the city would find me of the slightest interest, respectable or not.

‘Don’t be too sure of that, Don Roberto. Every foreigner who arrives here is photographed at the airport when coming through immigration – you noticed the big mirror, which was a see-through one from behind? A file is opened on everyone by the secret police, just in case – where they stay, who they meet, what they say about Paraguay. The big paranoia at the moment is Colonel Oviedo’s agents. A Brit would be a good disguise. Your profession, “journalist”, is immediately of interest to the pyragues – the hairy feet, as the spooks are called in Guarani. Your suitcases will already have been searched, and the number and type of your cameras will have been noted. The hotels always have a tame pyrague to do such elementary first moves. Although local film developing is not up to international standards it would be a good idea to get at least two or three films processed and printed up here, and leave the results around in your room when you are out and about – snapshots of the national monuments, parks, palazzi and so forth. This will show you are not saving films with compromising shots – military installations, the air force planes at the runway, say – to smuggle out and develop in UK or Brazil, as you came from Sao Paulo, and are flying back via there. Oviedo is just across the border in Foz do Iguaçu, and it could be very convenient for him to use a visiting British journalist to take a few useful snaps for him. He’d pay very well, I’m sure. You could have been recruited in London. There are certainly Oviedistas there who have already been in negotiations with the UK government as to what stance the latter might have if and when their man seizes power here. As you have at least two different cameras, I can’t help having noticed, one standard 35 mm, the other panorama, it would be a good idea to get at least one film from each developed, even if they can’t do the panorama properly here. Just to show you are not hiding anything. This is how the secret service mind works, you see, suspicions about ordinary things like cameras, which most Paraguayans don’t have and never use. Leave the cameras in your room, too, so they can be inspected. Notebooks, also. If you don’t, they may assume you have something to hide, and your cameras may be stolen, just to see what’s on the film inside. If you carry them with you all the time, this may mean you have to be attacked, possibly even killed, in order to get the films. Life is cheap here. It costs US$25 to bump someone off, I’m told – a policeman’s wages for a week – when he gets them, which isn’t often. It might also be a good idea to fax an editor in London, real or imaginary, a “colour” piece on Paraguayan wildlife, say – David Attenborough zoo quest sort of stuff – armadillos in the Chaco, pumas in the pampas, piranha in your soup, and so on. Say how much you are enjoying this peaceful, friendly country with its unspoiled, kindly people and charming, beautiful women. That is the sort of journalism they like, the pyragues, from foreigners. It will justify your existence here. Things not to mention are: 1) Oviedo and imminent, bloody coups d’état, which are called golpes in Spanish, by the way; 2) cocaine, cocaleros and drug smuggling; 3) Nazis and hidden Nazi gold; and 4) corruption and the crooked government – i.e. anything that is actually real. Keep all that until you get back to Europe. Alfie had an Interpol agent from France, a genuine Frenchman, mind you, not a local with Froggy papers, blown up inside his airplane as it was about to leave Asunción. It was on the runway, taxi-ing for take-off. Killed everyone on board, including the narco-cop, who had uncovered some embarrassing evidence of heroin smuggling among members of Alfie’s government.’

I thought privately that this was all highly fanciful, and that Alejandro was more than a shade paranoid, though I said nothing out of politeness: in fact I took his whole spiel as alarmist, of the sort those in the know love to plant in the minds of the timid newcomer. As events progressed, however, I began, slowly and reluctantly, to come round to the idea that some, if not all, of what Alejandro suggested might have a grain of truth to it. His words echoed in my mind, right up until the last moment, when sweating and frankly terrified, I sat waiting on the tarmac in a crammed exit flight, waiting to see if we were in fact going to be blown up before we took off. Things fall apart, the centre cannot hold, as W. B. Yeats sagely observed: the questions no one can answer are: a) how fast are they falling apart, and will they take me with them when they finally explode? and; b) will the centre be able to mount one last horrendous act of violence before it falls apart and bumps thousands off including oneself? An old hippy on the island of Ibiza who had hitched right round South America, including Stroessner’s Paraguay in the 1970s, had advised me laconically, ‘It’s very easy to get offed in Paraguay – paranoiaguay, as we used to call it.’ How right he turned out to be, and how little things had changed in thirty years.

Six

An Ambassador is Uncovered

Finding the British Embassy was not easy. Once, it had been downtown, lodged in an upper floor of an office building. Terrorism and attacks on British diplomats in other parts of the world had meant a whole new secure complex had been built far out in a new suburb which hardly anyone in town knew how to find. It was not even registered in the phonebook, and it was so new the large-scale map of the city in the hotel foyer wall did not include the suburb. Eventually, after contacting Gabriella d’Estigarribia, who was up on these sorts of things, the hotel receptionist did manage to phone the Embassy, find out the address, and book in an appointment for me with His Excellency, whose diary seemed as empty as mine – any day at any hour of any day would be convenient, it seemed. I spoke to the Embassy secretary myself, after all the toing and froing had been got over: she had a brisk, efficient manner and spoke excellent English, yet was not herself English. I wondered if it was the same lady who had fielded all those calls from ardent Paraguayans volunteering to take a swipe at the Argies in the Falklands War. Plucky little Paraguay had a reputation for trying to get into other people’s wars. Stroessner had volunteered to send troops to Vietnam, but Lyndon Johnson had turned him down; an unusual case of preferring someone to be outside the tent pissing in, than inside pissing out. A Paraguayan regiment or two, particularly of horseborne hussars, say, or lancers in 18th-century full-dress uniform, would have enlivened the bar scene in downtown Saigon, if nowhere else.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.