Полная версия

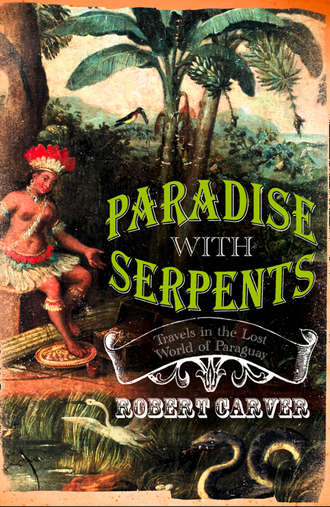

Paradise With Serpents: Travels in the Lost World of Paraguay

Madame Lynch was the mistress and éminence grise to Mariscal Francisco Solano López, the third of Paraguay’s dictators after his father Carlos Antonio López (el fiscal – the magistrate), and the founding father Dr Francia (el supremo – the supreme one). All of Paraguay’s dictators had earned soubriquets: Solano López had been el mariscal (the Marshal) and Stroessner was el rubio (the blond). If Oviedo ever came to power he would inevitably be el bonsai – people called him that already – unless it was el loco which he was called, too. Beyond simple description no one could agree about anything Madame Lynch had done. For the Colorados she was a national heroine, whereas the Radical Liberals saw in her a manipulative exploiter who bled Paraguay white, along with Solano López, whom they viewed as a criminal lunatic. Both of these ambiguous historical figures had been co-opted by Stroessner and his regime, and the cult of their heroism promoted assiduously. Madame Lynch’s remains had been brought back from Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris and buried in La Recoleta in Asunción. The man who had organized this transshipment, a Lebanese-Paraguayan, had profited from the occasion to import a large quantity of hashish in the coffin with the remains of Madama.

Often called ‘Irish’, Eliza Lynch claimed to have been born in County Cork of Ascendency, Protestant parentage, and educated in Paris. She was a woman of cultivation and taste, speaking French, Spanish and Guarani with fluency, and played the piano, sang and danced with distinction. She had attached herself to López in Paris when he had been Ambassador at large in Europe, arriving with a substantial entourage and ample funds, the first the independent Paraguay had sent across to Europe. López had made the Grand Tour through France, Italy, England and the Crimea, where he observed the war in progress. In France he collected Napoleonic uniforms for his army officers, and from England guns and steamships supplied by the London firm of Blyth Brothers, who were also to send out a stream of technicians to Paraguay which enabled López to build up his army, navy and arsenal quickly enough to take on the three other regional powers all at once, very nearly beating them. López and Lynch returned to Paraguay with a complete kit for DIY imperial splendour – Sèvres and Limoges china sets, a Pleyel piano, fabrics, sewing machines, books, pictures, manuals of etiquette and court ritual, ladies’ maids and dancing masters, curtains, furniture and antimacassars. López actually went as far as to have a golden crown designed and sent out from France, but it was intercepted at Buenos Aires, and he never managed to have himself crowned Francisco I – even though he was referred to as such in some outlying provinces of Paraguay. Considered a great beauty, Eliza Lynch was the first modern career-blonde to arrive from Europe in South America with a mission, and a protector with enough money and political clout to make her ascent possible. Eva Perón, native-born South American, trod very much in the footsteps of Madame Lynch. Both of them were reputed to have been common whores working in brothels in their youth.

Madame Lynch created a sensation among the Guarani Indians, to whom she seemed an embodiment of the Virgin Mary. To the Creole elite of old Spanish blood she was an interloper, and a putana – a whore. They refused to recognize her, and eventually, when López got into his stride, were exterminated for their pains. López already had a wife and children established before he left for Europe and the new, big ideas he imbibed over there. Madama, as Lynch became known, was set up in style by López in Asunción, and formed her own alternative Court in her houses, which she decorated and furnished in the latest Parisian style. She was the cynosure of wit, elegance and art in a backward provincial capital that was nothing more than a village by a clearing in the jungle on the river. She came into her own when López senior died and Francisco Solano took over supreme power. López and Lynch turned the Pygmalion story upside down – Dr Higgins the rustic hayseed instructed by the sophisticated Parisienne Eliza Doolittle. Paraguay has always been, it would seem, a country of strong, capable women and weak, vain, indolent, incapable men. Whatever small quantity of sense Solano López may ever have had seems to have been provided by his mistress, though her detractors claim that it was her evil genius which spurred him on in his disastrous military and imperial ventures. The idea of becoming Emperor of Paraguay was not particularly absurd; there were in existence two new-minted empires – Brazil and France – as well as the older Russian, British, Austro-Hungarian and Turkish imperia. The fall of Napoleon III’s empire saw the creation of a German empire to replace it. Nor was defeating Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil particularly ambitious. They were all weak, poorly led and disorganized. The problem was that Solano López was consumed with vanity and egotism, trusted no one, and set about killing off his family and anyone in Paraguay of any ability and competence. Had he done nothing, and let his generals, British technical experts and brave soldiers simply attack the enemy, there is little doubt he would have defeated them and become Emperor of southern South America.

What is not in doubt is that Madame Lynch introduced into Paraguay an element of courtly style, of elegance, of well-dressed chic which had never been seen before, and which among the upper classes, survives and flourishes to this day. Paraguay, under her aegis, became a place of masked balls, river-boat picnics with brass bands in attendance, elaborate full-dress evening dances, classical music concerts, theatrical and opera performances, and champagne suppers. Everything had to be shipped up the river, and before that across the Atlantic from France, but neither time nor distance was any hindrance to the dandies and belles of either the 18th or 19th centuries. The details of all the wine imported by Thomas Jefferson from Château Margaux to his estate in Virginia still exist today in the Bordeaux archives. The Madame Lynch belle-of-the ball legacy lives on vibrantly today, and one of the startling features which elevates Paraguay from, say, the Congo, which in other ways it closely resembles, is the old-fashioned chic and elegance of the rich in Asunción, who still dress in long white gowns, full evening dress, starched shirts and tailcoats, and attend high-society balls with bands, masters of ceremony, sprung ballroom floors and all the other appurtenances of courtly behaviour now more or less a memory in Europe. The Society pages of Ultima Hora revealed a social Asunción which looked like Paris before the First War – pearls, tiaras, wing-collars, black or white tie, patent leather shoes, full orchestras in uniform – all a thousand miles up the river and in the sub-tropical jungle. At the Gran Hotel I was witness to all this, for every weekend some celebration would be mounted in the ballroom: Strauss waltzes would echo from the Indian orchestra in dress uniform, and the belles of Asunción would trip the light fantastic while outside waiters in white-starched uniforms with cummerbunds would circulate with canapes and champagne on silver trays held high over their heads. The debutante balls of the season were all lovingly photographed and reported in the Society pages, everyone’s name printed in full; it made light relief after the litanies of crime, corruption and bankruptcy on all the other pages.

Asunción’s bizarre elite were really too much. In a city where so many were almost starving there were no less than four Tiffany’s jewellery shops, and the company was doing so well that they could afford to take out full-page advertisements in the papers promoting their latest imported deluxe items from New York. Whether she had or had not lived in the old estancia that had become the Gran Hotel, all this was certainly the result of Eliza Lynch’s meteoric passage through Paraguay. Without doubt she and López and their Court would have danced here, for it would have been one of the few ballrooms in the city of that time able to accommodate large parties. It was somehow very Paraguayan to have breakfast under an artificial, painted tropical sky, installed by emigre Sicilians, when outside through the open french windows real Paraguayan tropical birds sat in real tropical foliage, fed from time to time by indigenous Guarani servants. I was reminded of the old Chinese saying: ‘Is Chuang-zu dreaming of the butterfly, or is the butterfly dreaming of Chuang-zu?’

Five

Paraguay, Champion of America

The census had not been a success, according to the press. Incomplete, notorious disorganization, several suburbs of Asunción left out completely the journalists all reported. Perhaps it had all been as inefficient under Stroessner, only then no one would have known, because in those days the press had been allowed to report nothing but peace, progress and order – the regime’s apt motto, reflecting three much desired qualities in Paraguayan life, and notable mainly for their complete absence in the post-Stroessner polity. The students who had actually carried out the census with their clipboards and serious expressions, knocking on individual doors and demanding entrance, like latter-day emissaries of King Herod, had been paid 5,000 guaranis for their day’s work, sometimes only 2,500 guaranis. A bus ticket in Asunción cost 1,300 guaranis. Everyone had been restricted to their place of residence all day long, forbidden to take to the streets, which was why I had received so many sidelong glances and felt so much discomfort when I was busy striding about the town taking photographs.

Now at last, it seemed, the country had won an international accolade. According to Transparency International, Paraguay was the third most corrupt country in the world, after Bangladesh and Nigeria, and the most corrupt in the Americas, ahead even of Haiti and Colombia. Less corrupt than Paraguay were Angola, Azerbaijan, Uganda, Cameroon and Kazakhstan, among others. The least corrupt countries were Finland, Denmark and New Zealand, in that order. Corruption in Paraguay was not individual or sporadic, it was institutional and endemic. Nothing could be done without bribes at every level, from the simple policeman manning a roadblock to a cabinet minister approving a government contract. Anyone in a position to milk money from the system did so. The country’s economic plight was spelled out in its depressing list of negative statistics. There was a US$2,200 million external debt, the interest on which could not be paid, and a US$305,000 million budget deficit. Out of a total population of 6 million, 200,000 people were employed in the public sector, most of them unpaid for months or even years; 15.3% of the population was ‘openly employed’, 22% officially unemployed. There was an 8% illiteracy rate and 81% of the population had no health insurance. There was, of course, no government health service whatsoever; 33.7% of the population fell below the official poverty line of $25 a week and 16% (900,000) existed in extreme poverty, with no source of formal income at all. The most startling imbalance was the tiny proportion of public service workers – less than 3.3% of the population. In Welfare State Europe this figure stood at 45% or 50% of the population. But to employ so many people in the public services you had to tax people heavily – Europeans paid more than 50% of their incomes in direct taxes, pension levies and national insurance contributions, and then again on sales taxes, VAT and indirect taxes on such things as fuel, tobacco and alcohol. In Paraguay there was virtually no tax at all, which was what made it such a paradise for the rich. Huge tracts of Paraguay’s real economy were illegal – smuggling, drug processing and export, arms trafficking, fake cigarette manufacture and sale, car theft, cattle rustling and extortion, money laundering and the government cheating on contracts. The government was simply bypassed by private enterprise – criminal and legal – and the administration was too feeble and corrupt to do anything about it. Paraguay was a classic Third World kleptocracy, bankrupt but enormously wealthy, all the money kept out of the country in hidden bank accounts in untraceable offshore havens. When Belgrade was being bombed by NATO and accused of alleged sanctions-busting during the Kosovo war, the then President of Serbia, Slobodan Miloševic, commented that they really ought to be bombing the Cayman Islands, as that was where all the sanctions-busting was actually going on. Similarly, it would be futile trying to chase the missing billions in Paraguay as it was all hidden offshore.

The blame for the ruin of this rich and fertile country was laid squarely at the door of the Colorado Party by local historian Mida Rivarola.

The economic model invented by Stroessner turned a country that had been an exporter of agricultural products into an economy dominated by smuggling, crime and primitive State protectionism. When this model was exposed to more modern economies due to changes in the world it simply collapsed leaving poverty and corruption at every level.

Ultima Hora had produced a crime map of the country – drug smuggling, contraband, cattle rustling, piracy, marijuana cultivation, car theft, highway robbery, banditry, north, south, east and west, the whole of Paraguay was one large crime zone. Only bank robberies were in short supply, for most of the banks had closed, gone bust, or were defended by private security guards who looked like militiamen in flak jackets, armed with bazookas and heavy machine-guns. The streets of Asunción and other provincial cities were, from time to time, full of protesters complaining of all this. Mostly these demonstrations were peaceful, but they seemed to do no good: they belonged to the politics of theatre, the essentially futile statement in noisy collective form that people were unhappy with their lot, with the government, with the facts of Paraguayan life. No one had any answers or even any ideas except to borrow more money from the IMF, or to reimpose a dictatorship under Oviedo which, it was hoped, would at least limit the corruption to the Colonel and his cronies as in the days of Stroessner. The situation was almost beyond analysis, let alone solution. No one even talked of a Castroist, extreme socialist solution. For years young Paraguayans had been sent to Cuba to be trained as doctors. The Cubans hoped to induct them into revolutionary fervour: the opposite had been the result. They had all come back with horror stories of socialism in action. Even the bitterest critics of the Colorado regime admitted that Castroism was a dead loss and a cul de sac. There was no guerrilla movement like the FARC in Colombia, no potential President Chavez, a nativist anti-gringo rabble rouser, as in Venezuela. Paraguay was a pirate state, full of pirates, who complained only because the chief pirates were stealing all the booty, and they were getting little or none. The writer Jorge Luis Borges had wondered if his country’s fate might have been better if Argentina had become a British colony after 1820, when the Spanish had been expelled and the River Plate region fell under the economic influence of the British Empire. This reflection was made during the years of the repressive military regime in which everything had gone to the bad. ‘Colonies are so boring, though,’ he had concluded. Better then, in South America, to be theatrically badly governed than boringly well governed.

The great unanswered question hanging over the whole Third World is still the one posed by Goethe: ‘Injustice is preferable to disorder.’ What the colonial world had thrust upon it by the European powers had been injustice and order, which in almost all cases had been replaced upon independence by injustice and disorder. Asked if he thought India would be better governed after the British had left, Gandhi replied, ‘No, it will be worse governed.’ That had been a brave as well as an accurate prediction. A refugee white South African academic, safe in London, had moralized to me that it was ‘essential for Africans to make their own mistakes’ and learn from them, that colonialism only mollycoddled people. He, of course, did not have to suffer the effects of those mistakes, as he had fled, but he was happy to condemn the rest of the continent’s population to the Idi Amins, the Robert Mugabes and the Mobutus, as an inevitable learning curve. With freedom had come disorder, and injustice in another form. A new, native ruling class had formed, corrupt, authoritarian, immune from Western liberal criticism, more oppressive in most cases than the old white supremacists. Most ex-European colonies were in a far worse state than they ever had been under direct colonial rule. The democracies imposed on them by the parting masters had all failed and been replaced by despotism, oligarchy or anarchy. In some cases, after years of fruitless civil wars and disorder, that quintessential postmodern phenomenon, the failed state, had emerged. Paraguay was not yet a failed state, not quite: but it was not far off one.

Walking round Asunción it was evident that the fabric of the city was collapsing: garbage was uncollected, streets and pavements lay broken and unrepaired, buildings were not just unpainted and peeling, but crumbling apart, showing cracks and bulges in the walls. The dead banks, great glass and concrete mausolea, lay silent and empty, front doors chained and padlocked outside, dust and emptiness within. Groups of Indians from the Chaco, or simply homeless, poor people had taken up residence on strips of cardboard in their doorways – shelter at least from the tropical downpours. The local markets had spilled out on to the pavements, and the streets were full of rotting vegetables and fruit. A whole tribe of people lived by scavenging from this bounty. All around the centre of the city vendors had set up shop on the pavements, selling cans of food, bottles of wine, packets of biscuits – all imported. The hotels in the centre of town were completely empty. I went inside to talk to the receptionists who were pretty, smiled a lot, and had time on their hands. They all told the same story: ‘No one comes here now. Before, under Stroessner, there were tourists. Now nothing.’ Cruise ships used to come up the river from Buenos Aires for winter breaks, duty-free shopping expeditions. Now Argentina was broke, and Brazil was in deep trouble, too; no boats with tourists came any more. Asunción had become too dangerous. Right in the centre of town knife-wielding robbers held up buses, one man with a blade at the throat of the driver, the other passing down the bus collecting the passengers’ watches and wallets. On one such attack there had been an army major in uniform on board, a woman. She had had her face slashed. These attacks were happening all the time, every day, not at night in remote suburbs, but in the very centre in broad daylight. People were afraid to use the buses. Taxis were known to be used to kidnap people for ransom, or simply to rob and ‘disappear’ them. Many people walked, even long distances, rather than risk public transport, and I was one of them. The city was just about small enough to get around on foot. Everywhere, though, there was the same atmosphere of suspicion and mistrust. Each small shop had its assistant with a large automatic pistol. When they opened the cash box to get you your change their free hand would be on the pistol, finger curled round the trigger, in case you tried something. There were attempted robberies of these small stores every day, and shoot-outs leading to deaths. Every transaction, however small – a tube of toothpaste, a razor, a comb – involved a handwritten receipt with a carbon copy left in the receipt book: this was so the assistants could not steal from the till. The owners checked the takings against the carbon every evening and made sure the sums tallied. There were no smiles of welcome in any of the shops, rather wary caution or outright hostility.

That there had once been order and a degree of security was evident from the style of houses put up during the stronato. These were US-style villas or suburban bungalows with large windows and low fences, symbols of trust in the security the regime provided. Under Alfie a virgin could walk the streets of Asunción dressed in gold jewellery and risk no harm, people had told me, people who had opposed the old regime and hated the dictatorship. Then, everyone had been terrified of falling into the hands of the police. Now people had rights, but no duties. Improvised security precautions had been tacked on to these vulnerable homes of the Pax Stroessner era – iron grills on the doors and windows, razor wire on hastily erected high walls and steel fences, video security cameras and snuffling, whining guard dogs kept on short rations to make them hungry for burglar flesh. In all this I was again reminded of Los Angeles, with its neat notices in the gardens of dinky gingerbread cottages promising an armed response if you trod a step across the lawn.

The amenities of a capital city were absent in Asunción. There were no proper bookshops, only kiosks selling comics and religious kitsch. You could buy no foreign newspapers at all, anywhere. There were no coffee shops or bistros where you might relax in comfort and security. The park benches were filled with sleeping men, some of them police in uniform, and the parks themselves stank of human piss and shit and were full of rubbish. Concerts, recitals, theatrical peformances, art exhibitions were all absent; the few cinemas showed kung fu movies or sadistic pornography. There was one theatre show, I discovered, the English play The Vagina Monologues. It was a Buenos Aires production, and for macho Argentina the title had been redubbed The Secrets of the Penis. This was too daring for staid Asunción, and here it was running under the title The Secrets of the Male.

Although there were a few lurking stray dogs, with claw marks on their backs from unsuccessful vulture attacks, there were no stray cats at all – they were no match for the beady-eyed, telegraph-wire-perching birds of prey. A cat would only last a matter of minutes out of doors, I had been told; those that existed in Paraguay led cosseted, prison-like existences indoors, not unlike their owners. Small babies were never allowed out for the same reason – they would be snatched up from pram or cradle and torn apart and devoured in an instant. The man lost and waterless in the Chaco always saved the last bullet for himself, before the vultures tore his eyes out while he was still alive, but too far gone to defend himself. In the centre of town, by day, the police were about in force, lounging like the rest of the population, but kitted up in macho uniforms, with low-slung, black-holstered pistols. This fearsome image was assuaged to a great extent by the policemen’s girlfriends, who also hung about with them, talking softly and weaving roses and other flowers into their caps and uniforms with one hand, while holding their beaux’ hands with the other. These clumps of cops and lovers were particularly thick around the government buildings on the main plaza. One coup d’état had already been foiled and the Vice-President had been assassinated. No one knew who did it, so the authorities called in Scotland Yard, perhaps hoping that Sergeant Lestrade or Sherlock Holmes would be sent out to uncover the truth. From time to time passion would overcome the couples of policeman and lover, and they would detach themselves from the rest and make for a hot-bed hotel where you could hire a room by the hour. There was a constant traffic of heavily armed cops up and down the stairs of these establishments. As they hadn’t been paid for so long I assumed they had a good credit rating. It was probably not a good idea to deny tick to a Paraguayan cop.

In the centre of town, on the main street, was a ranchero’s outfitters; here you could kit yourself out completely with everything you needed to take on the Paraguayan estancia – leather chaps, saddles, bridles, lassos, boots, bombacha baggy trousers, saddle bags, revolver and rifle holsters, horseshoes, spurs and all manner of wide-brimmed cowboy hats. I spent ages in this shop, to the evident puzzlement of the assistants, fingering and peering at all these articles, which were laid out in piles on wooden shelves. The general ambience of the store was Tucson, Arizona, circa 1880. Unfortunately, I am large and Paraguayan gauchos are small, otherwise I would have equipped myself with one of almost everything. All the items were handmade and had a pleasingly rustic, archaic quality. If you wanted to set up a Wild West museum this would be the store to head for. Before Stroessner there had been few metalled roads, and Asunción was simply a cow-town; cowboys rode in from the Chaco, and tethered their horses at hitching rails in the capital. This shop must have dated from that era, but clearly still did enough business to stay alive, although I never saw anyone apart from myself and the staff in the place. Next door was the Café des Artistes. This had a vaguely Art Nouveau decor with marble top tables, red plush seating, a lot of mirrors, but no visible artistes, or indeed any clientele at all. The armoured, bullet-proof plate-glass windows and protective iron bars outside suggested that the absinthe-sipping decadents in floppy ties and Oscar Wilde-style velvet jackets had yet to come into their own in Asunción, or perhaps they’d all been gunned down in the civil war pre-Stroessner. It was always empty when I passed. Maybe all the artistes had left town or been shot up by the clientele of the cowboy joint next door. I liked the absurd juxtaposition of the two establishments, one pure 1880s, the other authentic 1890s, Arizona and Paris respectively: only in Asunción, surely, could you get a new set of spurs and a stetson with a rattlesnake skin swaggerband, then amble – or mosey, rather – next door for a few shots of Baudelaire, flowers of evil, and la sorcière glauque, as the fin de siècle crowd used to call the genuine sea-green wormwood absinthe, which, of course, though banned in France itself you can still buy in Paraguay. The waiters in the Café des Artistes were always asleep, heads on the bar, unless they’d been hitting the opium-laced papier mais cigarettes too hard, of course, and were actually on Cloud Nine.