Полная версия

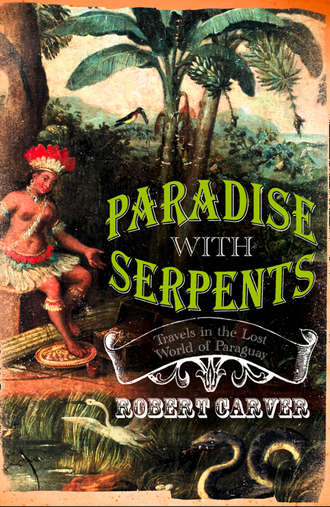

Paradise With Serpents: Travels in the Lost World of Paraguay

The capital of Paraguay was as empty as if a nerve gas strike had wiped out the entire population in their sleep. Not a soul stirred, not a car, not a bus or taxi moved. It was now 6.30am. On a normal day in such a tropical city the place would already be bustling. I took my black bag with me and my cameras. The best photographs I was ever going to get without being disturbed or harassed would surely be today.

It was by now 7.30, and the first groups of students carrying clipboards began to move about from building to building. These were the sharp-end censors who did the actual counting. On the corners of the blocks, soldiers and armed police had appeared, standing in pairs. Trucks drove around dropping them off. I noticed the soldiers were all small and dark, and when I strode by they avoided my eyes and instead looked at the ground or into the middle distance. With my purposeful air, my black bag and my camera, it was evident that they thought I was something to do with the census, and a figure of authority. Much later, when I asked Gabriella d’Estigarribia what impression I made on the local people she had smiled and said, ‘They think you are a German from the Technical Service. You stride about, and look angry, and stare at people. Johnny Walker! Very gringo and dangerous. You frighten them.’

This was a blow, I confess. I had thought I made a slightly better impression. The Technical Service was the euphemism given to the secret police who did the torturing under General Stroessner’s regime, and who had not gone away after his fall. What was evident on this my first morning’s walkabout was that at six foot I was very tall, and also very white, and the ordinary soldiers and police were very small and dark, and that the small dark people shrank from the tall white people in Paraguay, when they thought they had power. You wear your continent’s history on your face, in your build, and in your skin colour. Whether I was Brazilian, German or British did not particularly matter: I was a white European in a country and a continent that had been conquered by tall white people, and whose descendants still largely owned, controlled and dominated it to this day, along with much of the rest of the world. It was not a comfortable realization. However liberal, however multicultural one felt oneself to be, in this continent one’s safety, even one’s continued physical existence depended upon being defended by a corrupt and unjustifiably empowered regime’s police force, of which one felt afraid oneself. It is possible to forget you are white if you live in Europe: in the Third World it never is.

As I roamed about taking photo after photo, I wondered whether I, too, was supposed to be indoors along with everyone else. No one challenged me, but if they did I had a feeling that simply saying I was a gringo turista was not going to be a good enough excuse. But I wasn’t challenged, far from it – I was obviously avoided and ignored, and so I wandered about with increasing confidence. There simply were no tourists in Asunción, I realized, so my movements were interpreted as being in some inscrutable way official. Better not to ask, they would be thinking – I might make trouble for myself.

I had spent a long time looking for a café that was open where I might be able to get a coffee and some breakfast, but the whole city was completely shut – not so much as a kiosk or corner store open. Later, the next day, in the newspaper Ultima Hora, I had seen a cartoon of a shivering Paraguayan family indoors trying to hide from view their smuggled TV set, fridge, freezer, hi-fi and so forth. Outside was a burglar wearing a black mask and carrying a swag bag, knocking on their door. ‘No thank you – we know who we are,’ the head of the household was saying. In Paraguay, as in Turkey, the censors actually entered every house and counted the people in every room, and noted down all the things they possessed. Each property had a sticker pasted on the outside door to prove they had been inspected. ‘Smuggling is the national industry of Paraguay,’ Graham Greene had observed, when he visited the country in the stronato, as the Stroessner years were called. ‘Contraband is the price of peace,’ Stroessner had stated, defining it as official policy. With the second lowest per capita income in South America, Paraguay imported more Scotch whisky than all the rest of South America put together. It was almost all immediately re-exported to neighbouring Brazil, Bolivia and Argentina. Paraguay was sometimes known as ‘the Switzerland of South America’ not because of its non-existent mountains or ski slopes, but because it was the regional haven for hot money, millionaires on the run, shady enterprises of all kinds, numbered bank accounts and smuggled luxury goods. As in Switzerland, there were a lot of cows and a lot of pastureland – but you didn’t make much of a living out of those. ‘Switzerland is where all the big criminals come together to hide the profits of their swindles and thefts,’ Juan Perón, dictator of Argentina had said in the 1950s, before being ousted. He should have known: he had sent Eva Perón across to Europe in 1947 to bank their own ill-gotten gains in Geneva. The bankers had put on a special celebratory dinner for her. The British government had refused her a visa and denied her entry as a harbourer of fugitive Nazis and handler of stolen Jewish gold. It was estimated by the Allied Enemy Property Bureau after the Second World War that the Nazis laundered 80% of the loot they had stolen from the Jews and the countries they occupied through Switzerland, with the full knowledge of the Swiss, and the remaining 20% through Argentina, Paraguay, Egypt and Syria, all sympathetic to the Nazi cause. It was the Swiss authorities who had suggested the Nazis add a ‘J’ on to the passports of German Jews before the war, so the Swiss could tell who they were and refuse them entry. ‘Few things have their beginnings in Switzerland,’ observed Scott Fitzgerald, ‘but many things have their endings there.’ Seedier, poorer, more evidently corrupt and oppressive, Paraguay was a downmarket latino, South American tropical version, more like Albania in ambience. Already in my strolls around the city centre I had seen the empty shells of many monumental steel and glass banks, their doors locked and shuttered, beggars sleeping on cardboard under their massive porticoes. Inside you could see the desks and tables covered in dust, with empty cartons on the floors from where the computers and office equipment had been taken away. Like desecrated cathedrals, I thought, these were modern temples of money that had failed, abandoned by their priests, acolytes and devotees, who now worshipped abroad, in Miami and the Cayman Islands.

The night before, although tired after my 18-hour journey from London, I had gone out into the city centre, curious and impatient to get some first impressions. The broken pavements, sandy soil spilling out, potholed streets and grime-stained walls suggested a city down on its luck, and slipping into dereliction. Closed shops, broken windows, beggars, dirt, unpainted walls, shutters falling off their hinges: no one had spent any money on this city for a long time. There were armed police everywhere, hanging around, and the 19th-century stucco buildings suggested a derelict Andalucian provincial town in Spain during the early years of General Franco, just after the Civil War. But the Indian women crouched on the pavements selling tropical fruit and vegetables, herbs, potions and unknown fruit drinks were from the New World, not the Old. I had been recommended the nearby Lido restaurant by the hotel clerk. Right opposite the Pantheon of Heroes, this was an atmospheric 1950s-style soda fountain, with pink granite counter top at which one sat, huge fans churning the air above one’s head. The place was run by capable, sensible Paraguayan women of a certain age, who wore pink uniforms with little pink caps. I ordered a veal escalope à la Milanese, with salad and bread, and a Pilsen beer. I had inwardly groaned when the waitress had appeared carrying the beer, and a bucket of ice with a glass inside it. Ice in beer is a favourite – and disastrous – tropical invention I had experienced in Malaysia and Indonesia. But I need not have worried. The glass rim had not touched the ice, and the bottle of beer was opened and thrust into the bucket in place of the glass, up to its neck in frosty coldness, as if champagne in an ice bucket. This was a hot country where they understood cold beer. I had last tasted an iced beer glass straight from the freezer in Australia, a country where they also understand the needs of thirsty, heat-choked men. The Paraguayan beer, brewed to a German lager recipe, was very cold and very good. The food was excellent too: the salad had a flavour completely unavailable in Europe today unless you grow your own vegetables without pesticides and fertilizers. Native pessimism led me to abstract about a third of the escalope and secrete it inside a paper napkin in my bag, together with a couple of slices of bread. I had a feeling there would be no food available on the morrow for any price. I was right, too. Together with an apple I had left over from my flight, and some boiled sweets, this was all I had to eat until the day after the census.

It was dark by 6pm. The night fell suddenly, like a curtain. Wood fires started up, pinpricks of light, from the shanty town on the sandbanks by the river. A breeze from the river wafted up the characteristic Third World smell of sweat, smoke, excrement and spices. By day I had been in Franco’s Spain, but by night it was Java or Malaysia. There were small children everywhere, ragged, energetic, vociferous and hungry. The Lido had two private armed guards in khaki uniform, one inside by the cash desk, the other outside by the door. The children begged for coins as the customers left. There was a charity box by the cash desk which bore the printed label: ‘Give generously for the lepers of Paraguay’. I just hoped none of them worked in the kitchens. In England, I had asked my local medical centre what diseases were on offer in Paraguay, and what injections were required. It’s hard to impress a British National Health doctor, but Paraguay did it for my GP. ‘I say … malaria, dengue fever, yellow fever, blackwater fever, cholera, typhoid, jiggers, tropical sores, dysentery, plague, HIV, sleeping sickness, bilharzia … by golly, they’ve got the lot out there … it’s a complete Royal Flush. Why are you going, if I might ask?’

I muttered something about work. ‘Oh, and the llamas all have syphilis, due to the lonely herdsmen taking advantage of them in the altiplano …’ Surely not llamas, in Paraguay? I queried faintly. ‘Oh, sorry, my mistake, that’s Peru, next paragraph down. Oh and meningitis, leprosy, river fever, Lhasa fever … you know I think it’s easier to say what they haven’t got in jolly old Paraguay,’ he added jovially. ‘Ebola – they haven’t got that, it seems – yet.’ I’d had to go three times to his surgery for various shots over a couple of weeks. ‘Do please come back and see us again if … or I should say when you return,’ the doc had said cheerily. ‘The tropical medicine boys up in London like us to send up stool, blood and urine samples from people coming back from these sorts of places – you might pick up something really interesting, something new, even.’ Carver Fever, I thought, a hitherto unknown infection, carried by mosquitoes, incurable, causing paralysis, catalepsy, raging insanity, multiple organ failure and agonizing, lingering death by multiple spasm, also known as the Black Twitching Plague, after its gruesome effects. First brought back to Europe from tropical South America by the late travel writer Robert Carver, who was its first known victim, and whose body had to be cremated in an isolation hospital to avoid contaminating southern England … I could be famous: dead, and famous. I said I would stagger in on crutches, somehow, so he could apply his leeches to my depleted carcass. I thanked him, finally, after the last jab session, with thinly disguised insincerity and turned to go. ‘Oh, and I should take a plentiful supply of condoms – just in case any of those syphilitic llamas stray across the border … ha, ha, ha!’ His laughter echoed tinnily round the surgery. I gave him a weak smile, but I felt perhaps the joke lacked a certain good taste, or just simple fellow-feeling. On my first evening’s stroll in Asunción I was not particularly reassured to see a large sign with a vicious-looking mosquito on it in the Plaza Independencia, warning of dengue fever. ‘No hay remedio’ ran the Goyaesque rubric underneath – there’s no cure. Later, I was told that the dengue mosquito was slow and stupid and operated in Paraguay only by day, whereas the malarial mosquito was fast, intelligent and operated by night. The infectious dengue mosquito was male, the malarial female – make of that what you will. ‘Women are just as good as men, only better,’ observed D. H. Lawrence, who probably knew. The other Lawrence, T. E., contracted malaria while cycling in the south of France before the First War, while studying medieval castles. I had a great sack of anti-malarial and anti-every-other-damn-thing in my bags. If I had anything to say in the matter I was determined to avoid being immortalized in the medical history books.

The centre of old Asunción did have a certain faded elegance, reminiscent, especially after dark, of post-Baron Haussmann Paris, with tropical excrescences such as vultures perched on the telegraph wires, and impassive Indian women smoking coarse cheroots, squatting on the doorsteps. The park sported French 19th-century style wooden benches, white wooden slats held together by elaborate wrought iron, these boat-like contrivances designed for amatory ooh-la-la, even, perhaps, for complete copulatory performance, their arched backs swooning towards the grass. The palms rustled in the faint breeze, rats of impressive size scampering up and down the trunks with complete lack of pudeur, and groups of Indians in costume hunkered down for the night amidst the shrubbery, grouped around small, glowing fires on which they brewed their evening potations. By day, I later discovered, these impassive indigenos strolled about the town in loin cloths, amid the BMWs and Mercedes, proffering handicrafts, bows and arrows, and beadware, with very little evident enthusiasm or hope of a sale. These, I was told, were the Makká people, who had come in from the Chaco, the Paraguayan Outback that lay just across the river.

The old Post Office was the finest 19th-century stucco building I found, with a charming interior patio full of carefully tended tropical plants, and an elegant stone staircase up to the flat roof, where there was a café and an unrivalled view down across the square to the river beyond. Flags, of the Paraguayan variety, of all sizes, flapped energetically from many buildings in the strong evening wind that rose off the river, bringing the stink of the poor up into the centre of town. It was evident already that there were many poor, and they surrounded the city proper in their slums. A few of them slunk about furtively in the shadows, watched intently by armed police who carried shotguns, machine-guns and assault rifles, and wore six-shooters in black special-forces style low-slung holsters. I had been greeted jovially by a police officer as I walked about the square below the Post Office. He smiled elaborately and said that, with my permission, as I was evidently a foreigner, I would not mind if he gave me a few words of friendly advice. Under no circumstances was I to wander down the steps and into the favela – he used the Brazilian word for a shanty town – below us. The centre of Asunción was safe, he said, relatively safe even at night. The favela was not. I would be attacked, robbed and perhaps killed within minutes of going down there. It would be best if whenever I wandered around I kept an eye out for police and soldiers. If I could see police and soldiers I was probably all right – no one would attack me. If I couldn’t, then I was not safe. There was a great deal of crime at the moment, he told me, due to the unsettled conditions in the country. Not only foreigners were at risk, ordinary Paraguayans were attacked every day, even here in Asunción. I asked if everyone had identity papers, even the poorest of the poor, even in the favela. Everyone had papers, he said, absolutely everyone. Not to have papers was a criminal offence in itself. He wished me a good evening, smiled again and then strolled away. His warning and the slight chill in the air had suggested I should now retire for the night. I made my way back to the hotel and shuttered the windows tight. There were many mosquitoes on the wall and I spent half an hour killing them before turning in. I couldn’t really tell if these were the fast, intelligent variety or the slow, stupid ones. I rigged up my mosquito net, purchased in London, and crept under it. The bed was hard and uncomfortable. My room cost US$5 a night. I determined to move upmarket and out of the centre of town after the census was over.

Four

Du Côté de Chez Madame Lynch

Gabriella d’Estigarribia sat in the shade under a palm tree by the swimming pool and sipped her grapefruit juice delicately. She had a wide-brimmed straw hat on, her face in deep shadow, yet already the sun had caught the pale, fair skin of her face.

‘Foreigners come to Paraguay, find they can do nothing with the people, become angry, then give up, eventually, and go away again in disgust,’ she said evenly, not looking at me, but rather at the hummingbird which hovered like a tiny helicopter over the swimming pool.

‘Why is it so hard to get things done, for foreigners?’ I asked.

‘Not just for foreigners, for everyone. Some say it is the mentality of the Guarani people, who used to be called “Indians” before they were converted to Catholicism by the Spanish. Then, by a sort of unexplained miracle they ceased to be Indians and became Paraguayans. People say the Guarani live entirely in the present – the past is forgotten, the future unimagined. Remembering things and making plans for the future are both of no interest to them. Promises are made, events planned, but nothing happens – inertia sets in. From the first the Europeans had to use authoritarian means – force, coercion – to get anything done. The Jesuits used to whip their converts on the famous, oh-so-civilized, we are told, Reductions, as well as the ordinary secular colonial overseers on the plantation.’

‘That was a long time ago, surely. What about today, in the new post-Stroessner democracy?’

‘His Colorado Party is still in power. He was displaced by an internal coup because he had grown old and flabby. He was arrested at his mistress’s house. She was called Nata Legal – nata being “cream” in Spanish – that makes her Legal Cream in English, no? What better name for a mistress. He tried to call out the tanks but the only man with the keys for the ignition had gone off to the Chaco for the weekend – so no tanks. There was an artillery duel in Asunción – you can still see the pockmarks in the buildings from the shells – then he was gone, bundled off to Brazil where his stolen millions had been sent ahead. Now we have mounting chaos because no one is frightened any more. Corruption is universal. Everyone takes bribes if they can. Before, under Stroessner, you paid your 10% in bribes to the Party and then you were left alone. Under this so-called democracy you are constantly being made to pay up by everyone, and still nothing is done, because no one is forced to do it any more. You must have noticed the city is falling apart from neglect.’

In her thirties, married and with two small children, Gabriella came from an old Paraguayan family which had been in the country, on and off, since the Spanish Conquest. Her ancestors had come from the Basque provinces of Spain, as had so many of the other conquistadors. Like many of her Paraguyan ancestors, she had spent years abroad in exile, in her case in Miami, in Italy and in England, during the decades of political repression. We were sitting outside in the lush tropical garden of Madame Lynch’s tropical estancia. Once this had been a cattle ranch in open country, belonging to the mistress of the dictator López, now it was a hotel, surrounded by a well-heeled suburb of Asunción, an hour’s walk from the centre of town. You could get a bus or taxi down Avenida España, which made the journey much shorter, but the spate of robberies on public transport meant that many, including myself, preferred to walk. The Avenida España had well-armed police at frequent intervals, as well as motorized patrols during daylight hours, and most of the shops and institutions on either side had highly visible private armed guards sitting outside in plastic chairs with pump-action shotguns or automatic rifles across their knees. At each petrol station there was an army patrol permanently stationed, two or three uniformed men with automatic rifles. This was the route to the airport from the centre of town. If there was a coup d’état or a revolution, this was the route the outgoing government would flee along: clearly they wanted to make sure there would be enough petrol available to get them to their planes. It was the petrol supply for Stroessner’s tanks that had been under lock and key, I later learnt, when the crunch had come, not the ignition keys. Clearly, this government didn’t intend to make the same mistake. Stroessner still gave maudlin interviews to journalists from time to time from his hideout in Brazil, where he bemoaned the fact that he was a much misundertood former dictator – but then they all say that, those that survive. An avowed fan of Adolf Hitler, his secret police, known as the Technical Service, were among the most feared in South America. Cutting up political opponents with chainsaws to a musical accompaniment with traditional Paraguayan harp music was a popular finale, the whole ghastly symphony played down the telephone for favoured clients. Like his local hero the Argentine dictator Juan Perón, Stroessner had a taste for young girls – very young, pre-pubescent. When a daring journalist had once asked Perón if it was true that he had a 13-year-old mistress, he replied, ‘So what? I’m not superstitious.’ His reputation among Argentines had soared after this was revealed, the ultra-young mistress being seen as a sign or both power and virility. The 13-year-old in question used to parade around Perón’s apartment dressed in the dead Eva’s clothes, to the slothful admiration of her ageing beau. Stroessner was reputed to favour the 8–10 age group. His talent scouts waylaid them outside school, from where they were taken to discreet villas to be enjoyed by the Father of his People. If they performed nicely they and their parents would be sent on a free holiday to Disneyland in Florida, the nearest Paraguayans can get to Heaven without actually dying first. Stroessner, the half-Bavarian, half-Indian dictator had sent a gunboat down the river for Perón, the mulatto dictator, when he had taken refuge in the Paraguayan Embassy, after his overthrow. Forced into exile, Perón had fascinated the young supremo by recounting his adventures and reminiscences. ‘They used to worship my smile – all of them!’ he cried. ‘Now you can have my smile – I give it to you!’ and here he had taken out his brilliant set of false teeth, and passed them across the table to the startled Stroessner. Perón had found Paraguay too dull, and he had to agree to abstain from political intriguing in Argentina, which was irksome, so after a short period of rustication up the river he had taken himself off to the Madrid of Generalissimo Franco, where he lived in exile with the mummified corpse of Eva Perón upstairs in the attic of his Madrid villa, surrounded by magicians and occult advisers. The mummifier, Pedro Ara, who had taken a year over his task, had used the ‘ancient Spanish method’ and had charged $50,000 for his work, a bill that was never paid. Throughout the last weeks of Eva’s agonizing illness the embalmer had stood close by on guard in an antechamber, night and day, waiting in anticipation, for he had to start the process of mummification the instant she died ‘to render the conservation more convincing and more durable’. Her viscera were removed entirely and preserving fluids were sent coursing through her entire circulatory system before rigor mortis set in. Some areas of her body were filled with wax and her skin was coated in a layer of hard wax. The complete process was slow, painstakingly slow. After the fall of Perón, the military mounted ‘Operation Evasion’ in which the body of Eva Perón was ‘disappeared’ to prevent her becoming the focus of a popular cult; for many people, particularly women and the poor, she has already become a saint.