Полная версия

Birds of New Zealand, Hawaii, Central and West Pacific

TECTONICS The outer mantle of the earth is formed by solid rock (the lithosphere), covered by an accumulation of sediments, volcanic products and changed basic rock (the crust). The lithosphere overlays the asthenosphere, a mantle of plastic flowing rock.

The lithosphere is horizontally subdivided into seven or eight major plates and many minor plates, which ride on the asthenosphere. Some of these plates and parts of them are denser and heavier, lay lower and form the floor of the oceans. The plates move in relation to each other:

• at spreading (divergent) boundaries (A1);

• at collision (convergent) boundaries (A2); and

• at transform boundaries (A6), where two plates move in opposite directions.

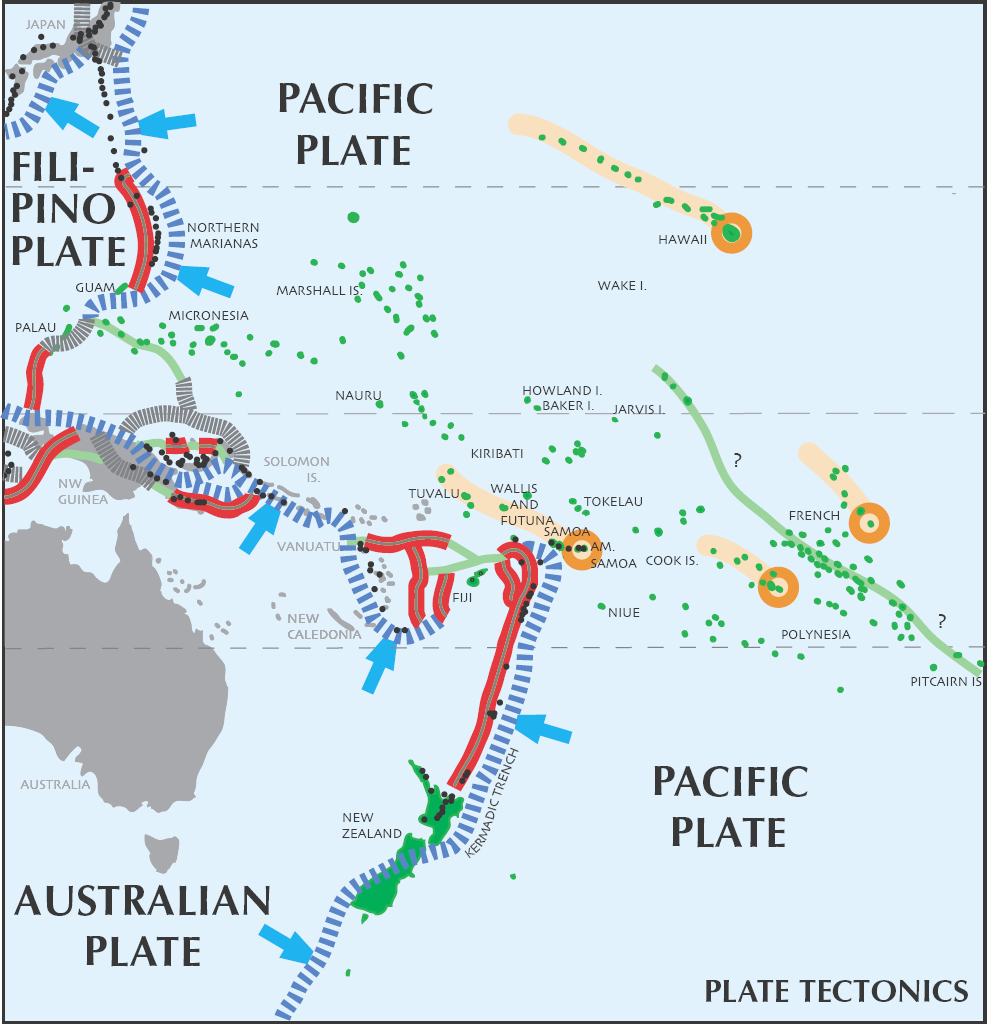

The area covered by this book is dominated by a convergent border between the oceanic Pacific Plate and the continental Australian and Filipino Plates (see map ‘PLATE TECTONICS’).

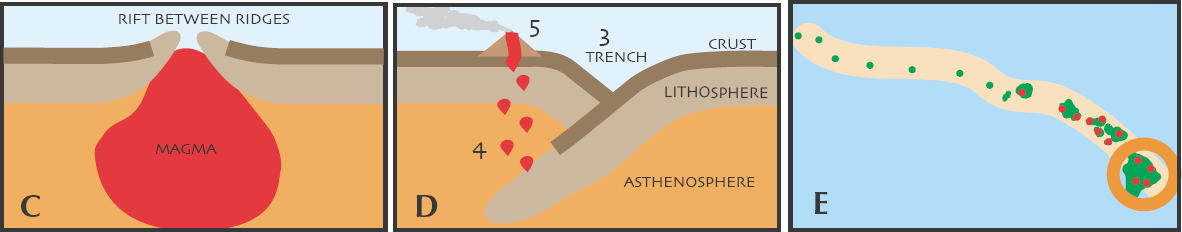

Tectonic plates separate (or diverge) from each other along a 80,000km long, mainly mid-ocean network (A1) that encompasses the earth. Nearest to the area is a network segment along the west coasts of North and South America. A typical spreading (or divergent) zone (C) can be described as a pair of parallel ridges on both sides of a rift. The rift bottom fills itself with upwelling, red-hot magma, which drives the plates apart and forms new ocean floor.

Collision boundaries are zones of subduction, where heavier oceanic plates dive under lighter continental plates as shown in A2 and D. These zones are marked by a deep trench (D3). When the crust, together with lithospheric material, sinks into the asthenosphere it is heated to such a high temperature that magma chambers (D4) are formed, which float to the surface forming rows of volcanoes (D5) arranged in island arcs (the Kermadecs and Northern Marianas are typical island arcs). These arcs form a sort of perforation, along which the edge of the overlaying plate is often torn off and dragged under itself on the back of the submerging plate.

Other types of conflicting boundaries are also possible (A6), for example, where plates or plate fragments rub along each other under a sharp corner.

The speed of spreading is unevenly dispersed along the mid-ocean ridge system. Tensions are solved by many fissures (A7) perpendicular to the rift. The rift segments (B8) shift in relation to each other; the parts of fissures between rift segments are called transform faults. The movement at their sides is in opposite directions, which may cause volcanic activity. The outer parts of the fissures are called fracture zones; these separate areas moving in the same direction, which causes no or only low volcanic activity.

Here and there, far from the edges, magma penetrates through the ocean plate. These places are known as hotspots (E); hot magma wells up via these holes giving birth to volcanic islands at the surface. Because the ocean plate moves in a north-westerly direction the hot spots keep drilling holes, forming chains of islands, the youngest being the most eastern one. The Hawaiian islands are a good example.

The map ‘PLATE TECTONICS’ also shows a transform fault (green line on map), running from the Nazca Plate (near South America) via the Pitcairns to the Line Islands, which could have produced the many islands of the Pitcairn, Tuamotu and Line Islands. However, their origin could also have been a hot spot near Easter Island.

REEF BUILDING There are many species of coral organisms. The group that can build a reef is only found:

• in clear salt waters;

• at depths shallower than 50m (beneath this depths the coral skeletons change to coral limestone, darker yellow-green in figures);

• with an optimum temperature of 26–27°C; and

• strong currents and/or heavy agitation (otherwise food particles are unable to reach the tentacles of the polyps).

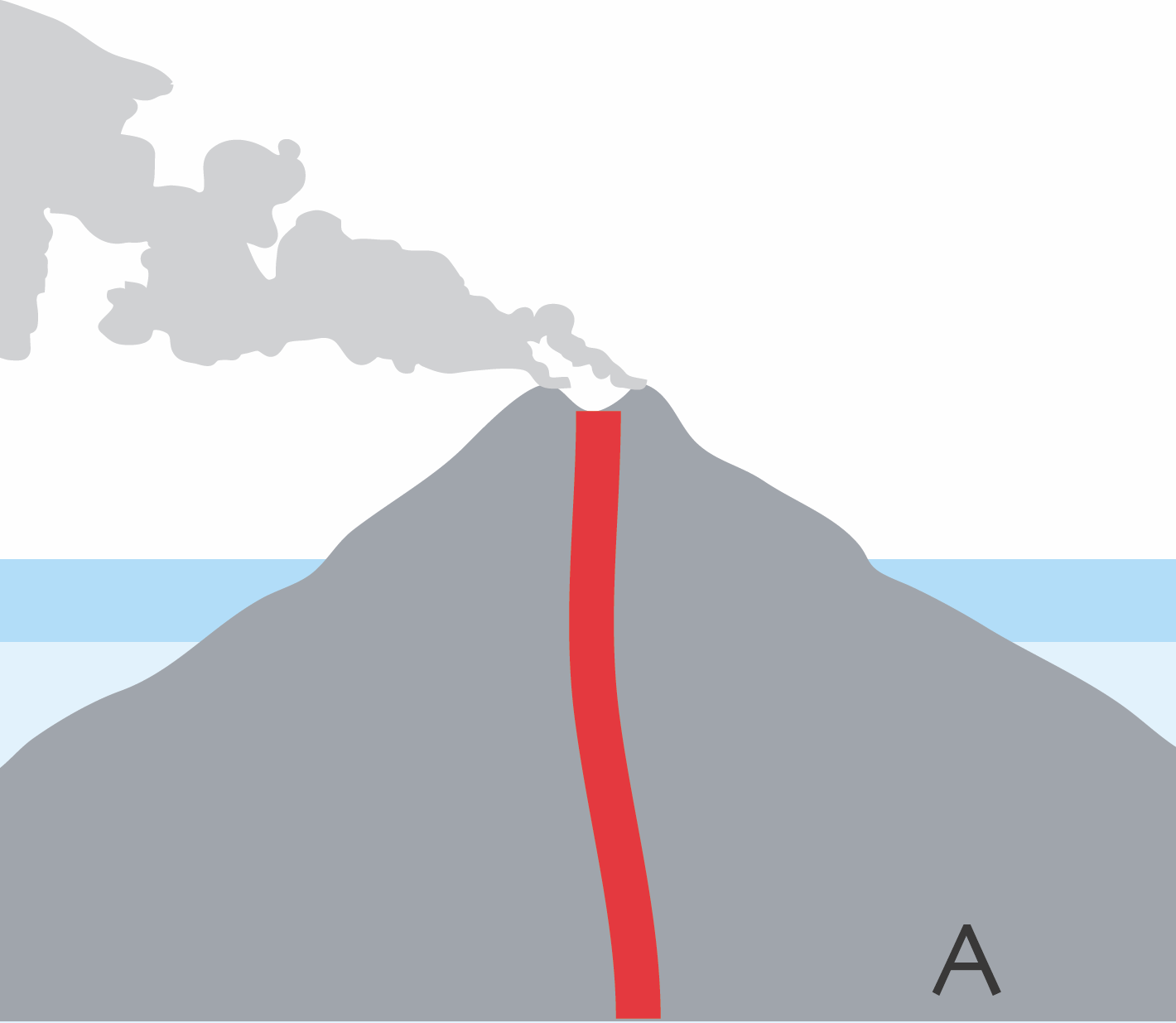

Most if not all tropical Pacific islands have a volcanic origin. Reef building starts as soon as a new volcano has emerged (A) and coral larvae have been carried in by ocean currents.

The first stage is a fringing reef (B) at a short distance from land and normally en-compassing a shallow lagoon. It takes about 10,000 years from stage A to reach stage B.

In the course of time the volcano erodes or the local ocean bottom subsides. If coral growth can keep up with the speed of this process, a barrier reef (C) is formed on the base of coral limestone; note the wider, locally deeper lagoon.

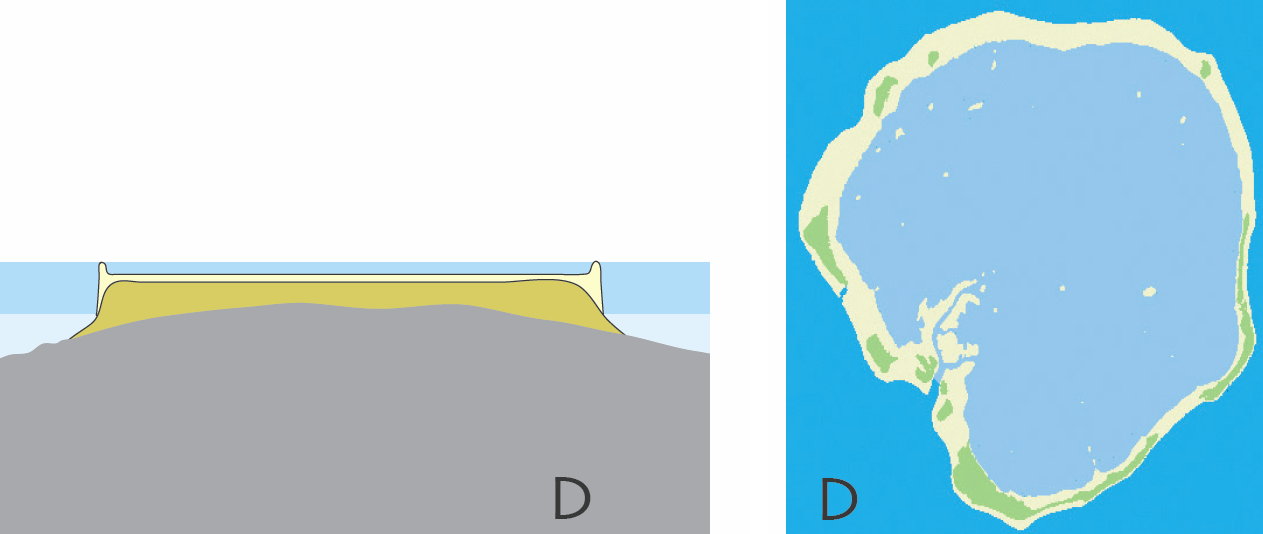

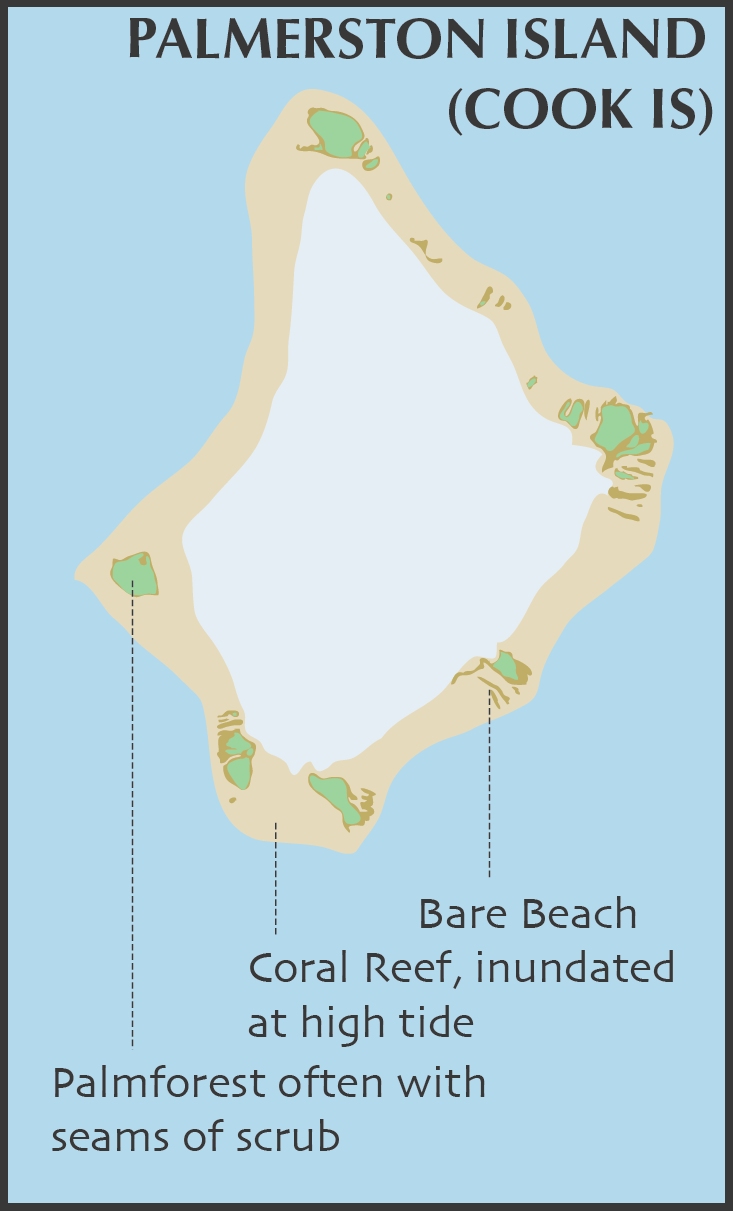

Ultimately, all land will be eroded, and the barrier reef will become an atoll (D) en-closing an open lagoon. The process from A to D can take 30 million years.

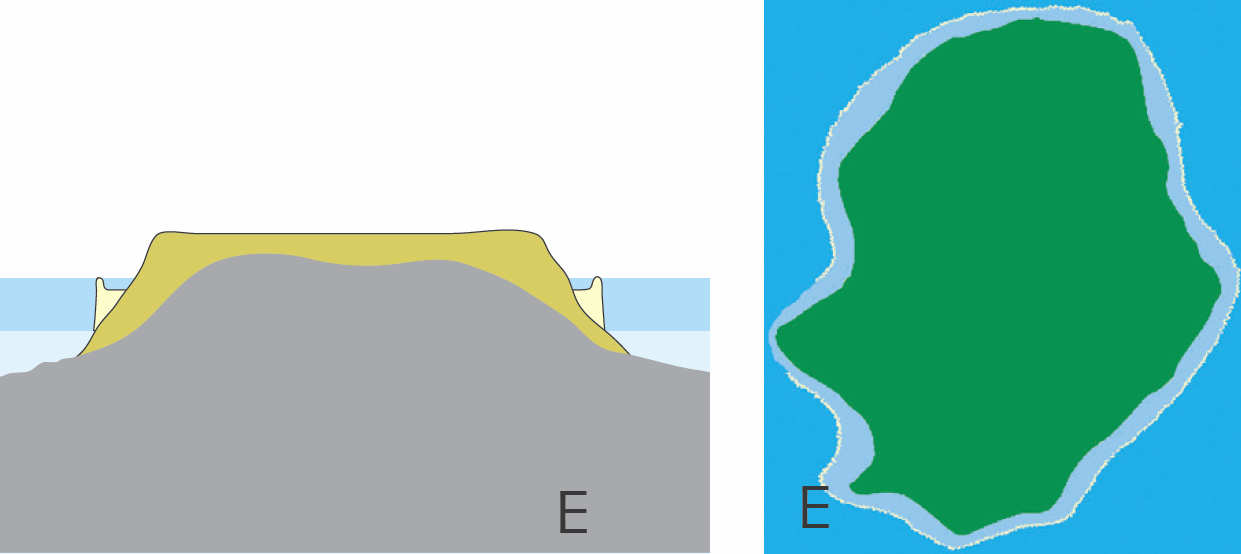

It is possible that an atoll can be uplifted by movements in the earth’s crust, by which an uplifted coral island is formed. A limestone rock emerges (E) and becomes encircled by a fringing reef.

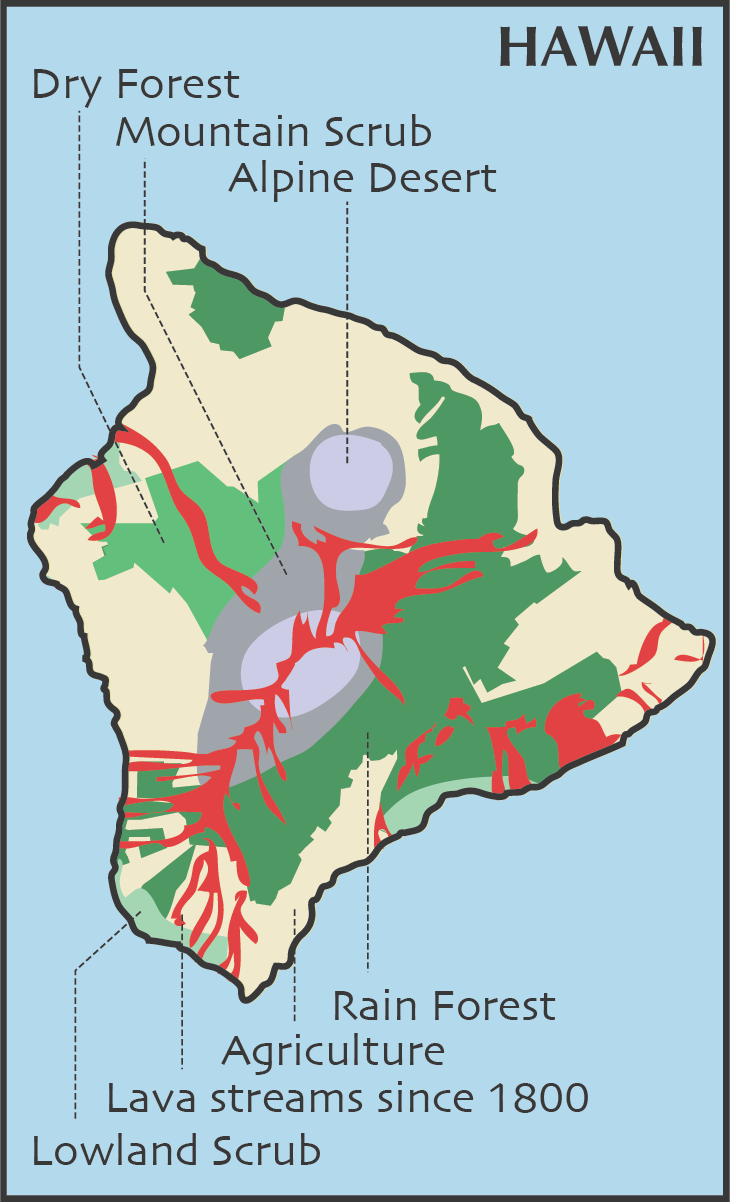

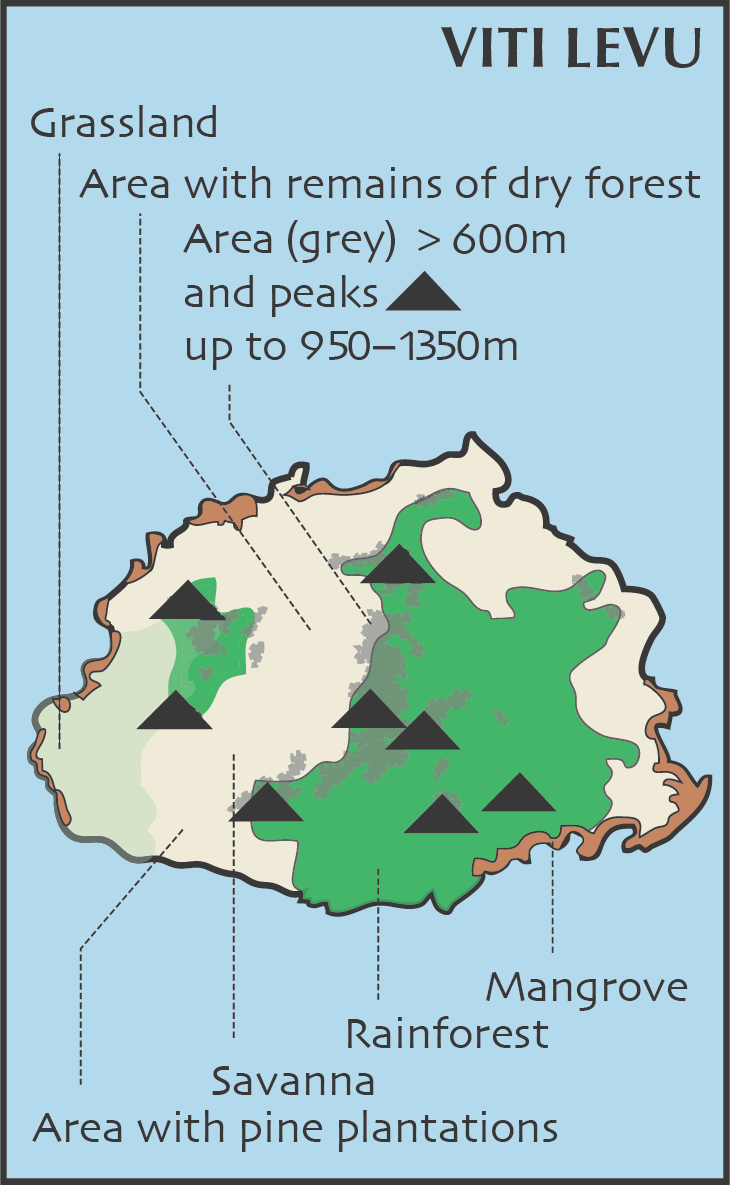

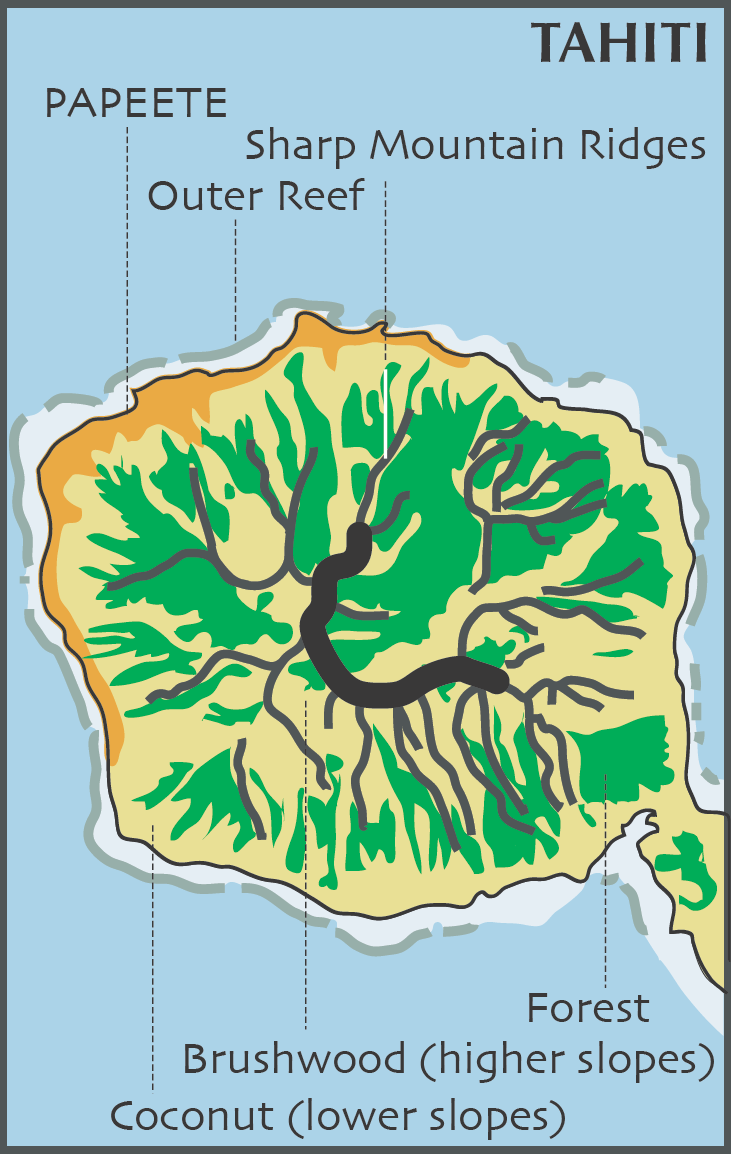

LAND USE AND VEGETATION TYPES Once most islands were mainly covered by forest. The arrival of man brought about many changes in this environment and the following are the main present-day habitats.

Ocean

Open Tropical Ocean: warm water contains less prey (fish, squid, etc.) than cold water, therefore most seabirds in the tropical ocean are more numerous at places where deep cold currents from higher latitudes well up above (under) sea mounts (submerged volcanoes) and at the western edges of the Pacific.

Temperate Ocean: water temperatures between 10 and 18°C, found between the tropics and 48°S and N. Rich in oxygen and nutrients, very rich in fish (less species than in tropical seas, but often in large shoals) and in other life forms.

Coastal habitats

Lagoon: shallow, clear water rich in food for terns, gulls, noddies, tropicbirds and frigatebirds.

Seashore: especially important for migrating shorebirds.

Mangrove: mangrove stands support many bird species and form a habitat where heronries are often found.

Littoral Forest: the forests and thickets bordering the beach.

Lowland forest types

Lowland Dry Forest: found at the dry north-western side of high mountain chains, where the rain, brought in by the eastern trade winds, is released on the eastern slopes. All forms of dry forest are almost completely transformed to agricultural use. In the mixed exotic/native remains a few of the original endemic bird species may be found, plus many alien species.

Lowland Rainforest: as highland rainforest but with a more diverse range of tree species, denser undergrowth and many tree ferns.

Agricultural habitats

Coconut/Breadfruit Forest: found in the coastal areas of many Pacific islands. Mixed with species such as guavas, mango and Ficus. This is an ancient man-made habitat.

Farmland: food crops, fruit orchards, floriculture, vanilla, etc.

Savanna: low production grassland with some tree cover, many breadfruit shrubs and dominated by exotic grasses. Often replaces (dry) forest after repeated burning.

Grassland: areas dominated by grasses with little tree and shrub cover, also replacing former forest. Savanna and grassland in Pacific islands are normally the result of human activity.

Wetlands

Wetlands: rare freshwater habitat in the Pacific; most original wetland is drained and changed to crop- and grassland. Wetland bird species are now dependent on man-made ponds, reservoirs, sewage fields, etc.

Upland forest types

Production Forest: mainly Caribbean Pine or Eucalyptus plantations.

Upland Dry Forest: once covered about one-third of the lar-ger Fijian islands and also was common at the leeside of the Hawaiian islands; now greatly altered to savanna with sparse vegetation.

Montane Rainforest: various forest types united by high humidity and limited temperature variations. Exact timing of dry season varies. Characterised by epiphytes and mosses. This habitat has often disappeared from the smaller islands and the remains on larger islands are threatened.

Cloud Forest: the highest parts of rainforest, which are characterised by a high incidence of fog.

Secondary Forest: new natural forest where the original forest has disappeared. As a habitat it is highly variable, from low woodland to tall forest with more open canopy than virgin forests and lacking old emergent trees.

Other habitat types

Lava Plains and other bare ground at high altitudes: for some bird species this forms an important habitat (Hawaii Goose, Omao, Tahiti Petrel, White-tailed Tropicbird).

Some Basics for New Zealand

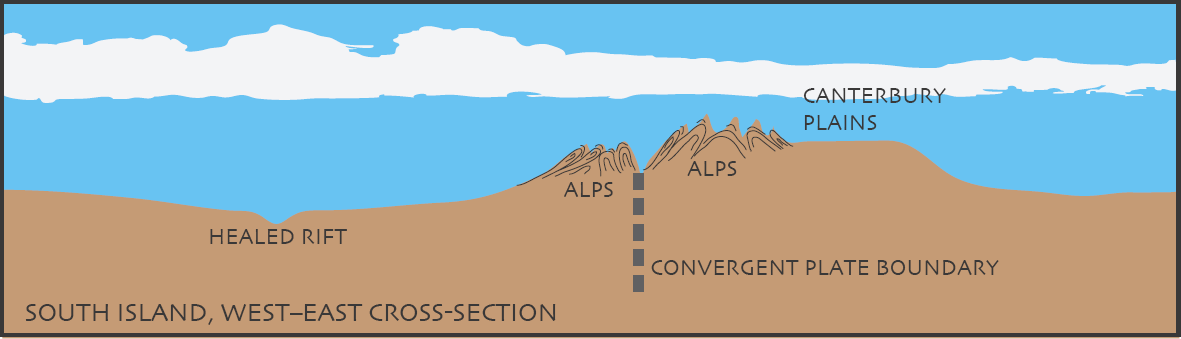

GEOLOGY The core of New Zealand was pushed, compressed and folded up against the Australian area some 370 million years ago. About 300 million years later (or 70 million years ago) New Zealand and Australia were separated along a rift that created the Tasman Sea. The rift ‘healed’ and 25 million years ago the eroded and flattened remains started to be uplifted again.

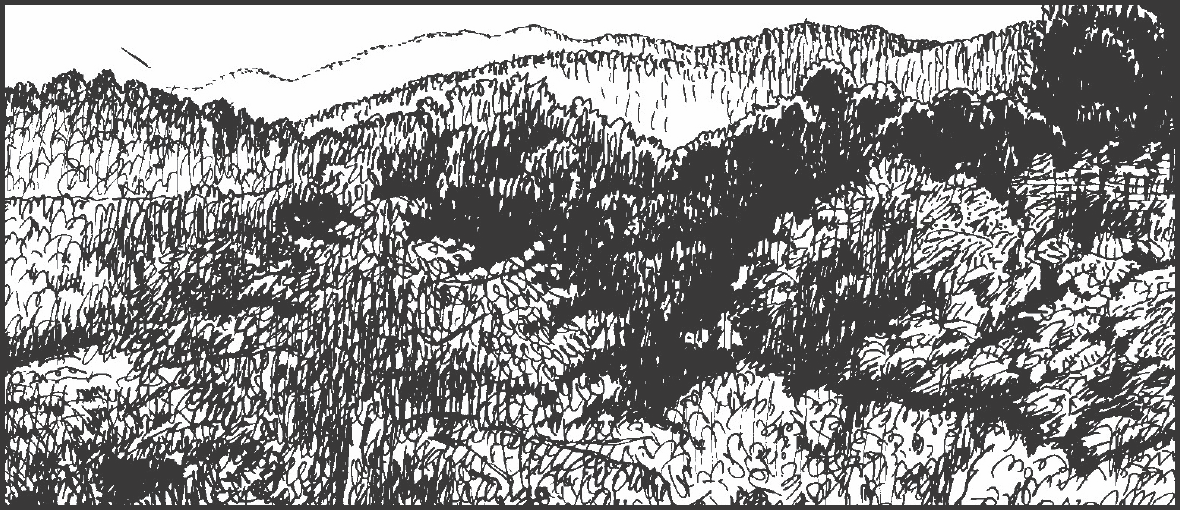

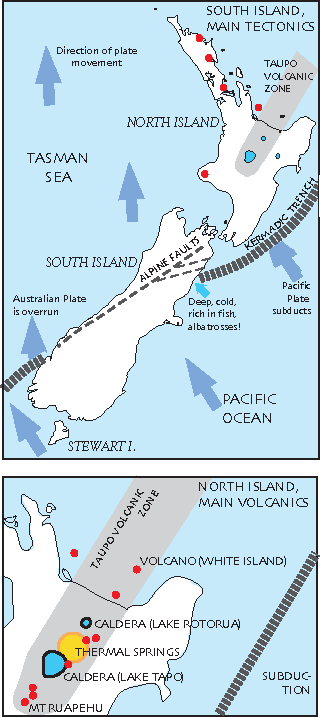

South Island is dominated by a row of Alps over the full western length. The subduction processes in the trenches north and south of South Island are contrary to each other, pressing the alpine area together. Along the main Alpine Fault both ‘Alp-halves’ are sliding along each other (the western ‘half’ moving faster north). Secondary faults are forming the highlands near Kaikoura. This is also the place where the deep Kermadec Trench brings cold, fish-rich water near the coast, attracting a host of seabirds.

North Island is dominated by volcanic activity. The Pacific Plate dives under the Australian Plate that carries the island. Where the plate sinks into the liquid-hot asthenosphere, magma is released and ‘floats’ to the surface forming an arc of volcanoes in the Taupo Volcanic Zone. In this zone and elsewhere there are several lakes in places where once large to very large magma chambers exploded (each one forming a ‘caldera’), after which the remains collapsed and were filled by rain water. It is also the zone where many hot springs are found; the water that surfaces here (often as steam) is heated deeper down in the earth’s crust. The volcanoes and calderas outside the Taupo Volcanic zone are mainly remnants of older volcanic arcs.

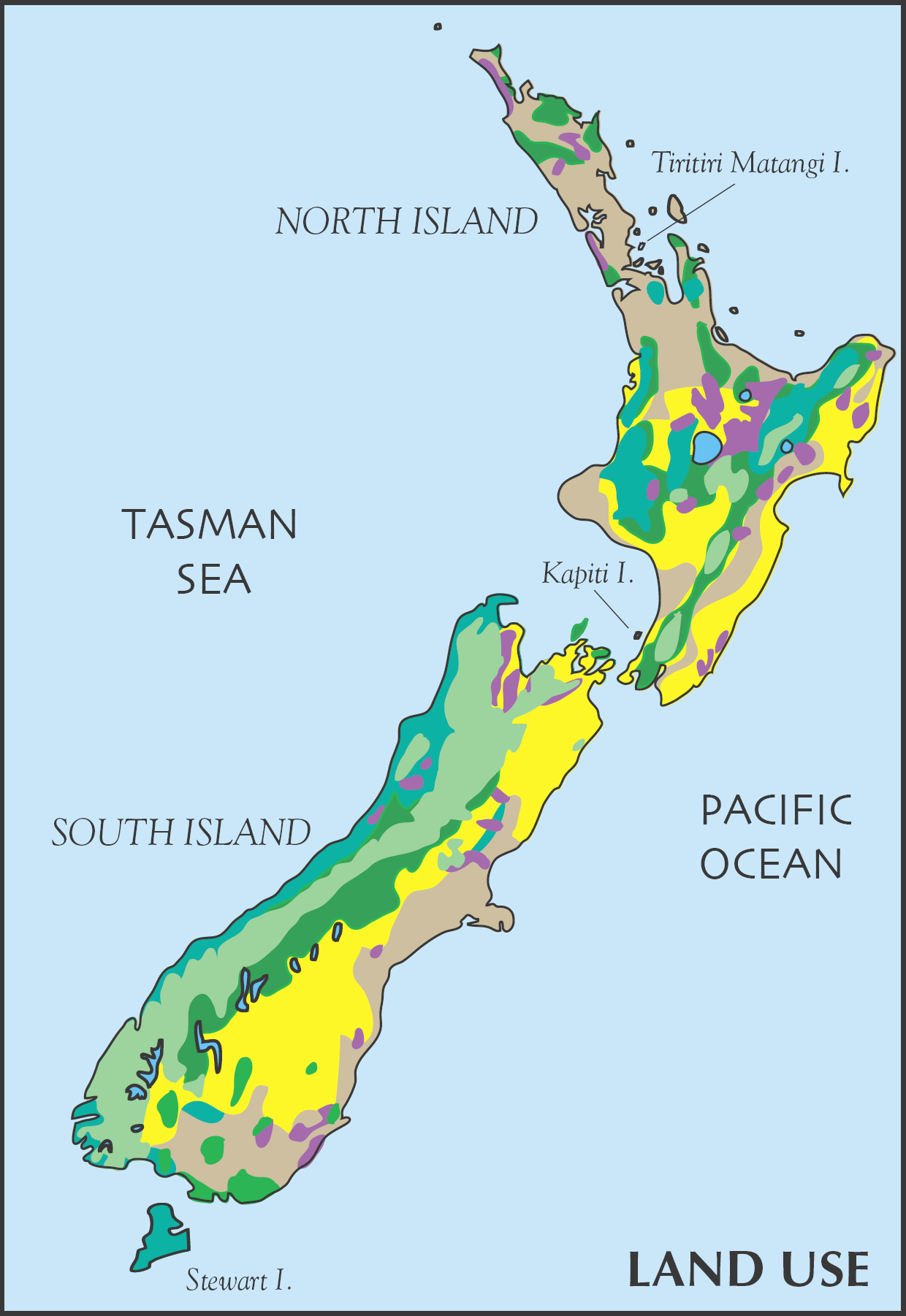

LAND USE AND VEGETATION TYPES Originally the greater part of New Zealand was covered by forest. After the arrival of the Polynesians (ad1000) and later on the settlement of the Europeans (from about ad1840) more than 50% of the forest was cleared, mainly by fire and grazing. Origin-ally there were no mammals in New Zealand except seals and three bat species, but when the first people arrived they introduced unwillingly or with full intent a wide range of animals, which started to compete with or to live on the native flora and fauna, driving many endemics to complete or near-extinction. The most dangerous intruders were black rats, mice, feral cats and possums. The latter not only eat eggs and nestlings of indigenous species but also the saplings and fresh shoots of indigenous trees and plants. The best places to see remaining endemics are a few islands and a single mainland sanctuary that have been made predator-free.

Before the arrival of the Europeans there were very few deciduous tree species, the 13m-high Tree Fuchsia (Fuchsia excorticata) among them.

The main habitats include the following:

Farmland, orchards, high producing grassland: together covering about 24% of the total land area.

Extensive grasslands: low vegetation, mainly with exotic and indigenous grasses. Livestock tend to be grazed over large areas. Some extensive grassland may have conservation or recreational uses.

Mosaic of different types of forest and farmland: among these is coastal forest, which is not very tall and is made up of plants that can tolerate salty winds. It generally lacks large conifers and has fewer vines and epiphytes. The canopy is dense and wind-shorn.

Lowland forest: resembles tropical rainforest, but is less rich in species. Found mainly in the northern half of North Island. A typical species is Kauri, a gigantic conifer with small oval leaves. Further south other tall species such as Southern Beech dominate. In most places all or most tall trees have been felled.

Upland forest: dominated by Southern Beech. Undergrowth less dense than in lowland forest. Before the introduction of possum, deer and goat, was rich in berry-producing shrubs.

Planted forest: mainly pine species, but also eucalyptus. Often with rich undergrowth of native plants. Covers about 7% of total land area.

Lakes: the lakes of South Island are drowned glacier valleys, those of North Island are mainly water-filled calderas (collapsed magma chambers).

Note: most natural inland wetlands of New Zealand have been drained for agriculture.

The Birds

Island Avifauna

The area covered by this book is characterised by its immense water surface, its countless small islands and the often enormous distances between them. This makes the avifauna typically island in character.

Of the 125, worldwide recognised true seabirds (albatross and petrels), 87 (or 70%) occur in the area.

As a result of the islands never having been connected to other land masses, the birds that are present have arrived on their own wings or with sea currents, by evolution or by human introduction (Polynesians and Europeans). About 70 species (9%) have been introduced, at least 201 species (25%) are endemic, so about 510 species came unsupported from elsewhere.

Before the arrival of humans there were no mammals in the area, except seals, bats and fruit-bats. There were not many birds of prey either. Many bird species could therefore afford to lose the ability to fly; 12 flightless species (excluding penguins) can still be found, namely five kiwis (all species), three rails (Weka, Takaha and Henderson Island Crake), three ducks (Auckland Duck, Auckland Teal and Campbell Teal) and one parrot (Kakapo).

The arrival of man with his domesticated animals and stowaways, such as black rats and the wilful introduction of predators such as weasels and stoats (as means to control other introduced animals such as rabbits), meant the extinction of many species. Fairly recently it appeared that avian diseases spread by mosquitoes have been responsible for the extinction and near-extinction of several species on the Hawaiian Islands (e.g. the Hawaiian Crow). In the mid 1960s the Brown Tree Snake sneaked into Guam. Without the natural predators of the snake or adequate defence by the autochthonic birds the Guam Flycatcher was extirpated and the Guam Rail could only survive in captivity.

An appendix to this book presents a list of 59 species that have become extinct since 1800.

The islands’ isolation has also had these effects:

• many species are fearless and docile. Indigenous birds in New Zealand, for instance, are often easily approachable;

• the genus Acrocephalus spread over many islands and split up in 12 endemic species; these differ mainly in the degree of leucism. The Tahiti species occurs also as a rare melanistic morph;

• islands tend to produce dwarf (none in the area) or giant species. The giants are extinct (unless one wants to consider Takahe, the world’s largest rail and Kakapo, the world’s heaviest parrot, as such). Extinct are the ten ostrich-like, forest dwelling Mao species in New Zealand (the largest reached a length of 2.7m). They were preyed upon by the likewise extinct Haast’s Eagle, which, with a length of 1.7m, was the largest raptor that lived in historical times. Other giants – likewise extinct – were Moa-nalos (giant ducks from Hawaii), Vitilevu Giant Pigeon and Eyles’s Harrier from New Zealand;

• a large amount of endemics. An endemic is a species that occurs only in an area with well-defined boundaries, such as a continent, a country, an island or a habitat. In this book 201 species are mentioned as endemic; only those, occurring with their full life-cycle solely in one of the 20 countries of the area, are treated as endemics, but does not include those restricted to, for example, a group of countries or the whole area. Subspecies are incidentally mentioned as endemic in the captions.

The Endemic Species of the Area

The following pages show maps and the endemics as thumbnails (not depicted to relative scale), arranged per country. The numbers preceding the species refer to the plates and numbers of the species on the plates, while the numbers at the end of the entries refer to the islands on the maps of the countries where the species occur.

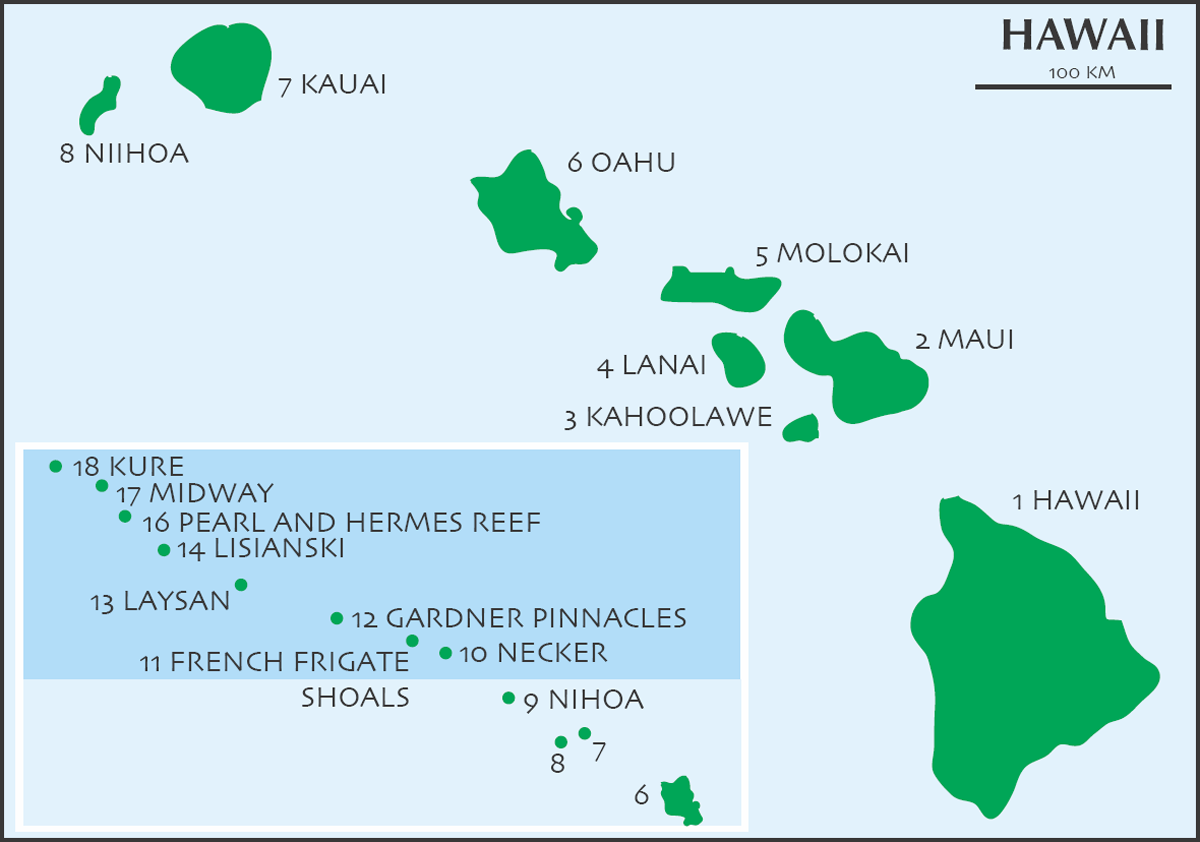

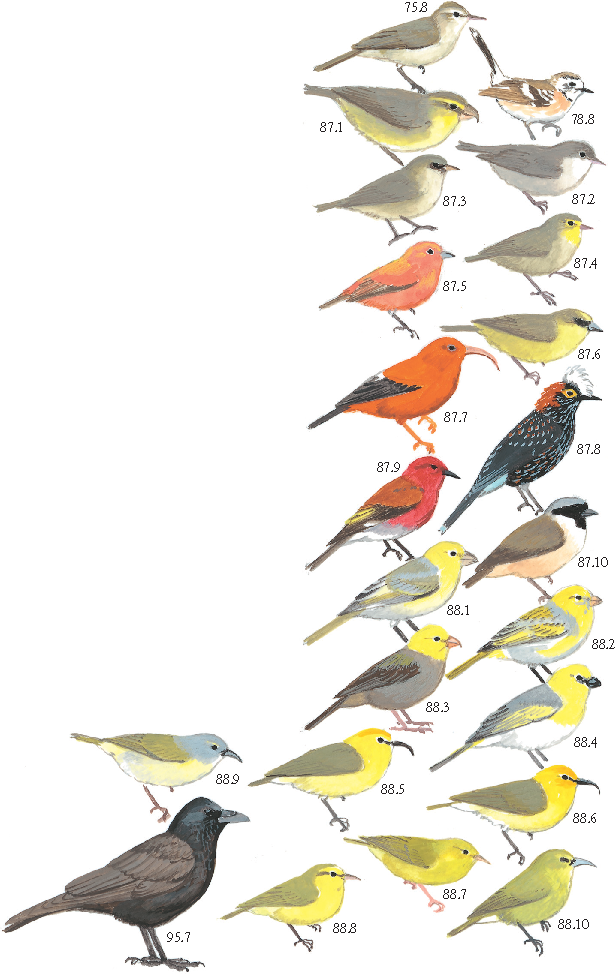

Hawaii Endemics

304 species, including the following 33 endemics:

11.6 Hawaiian Petrel Breeds Ha 1,2,4,?5,?7

Pterodroma sandwichensis

24.6 Hawaiian Goose Ha 1,2,5,7

Branta sandvicensis

27.2 Hawaiian Duck Ha 1,2,6,7,8

Anas wyvilliana

27.4 Laysan Duck Ha 13,17

Anas laysanensis

32.6 Hawaiian Hawk Ha 1

Buteo solitarius

38.7 Hawaiian Coot Ha 1–7

Fulica alai

74.1 Omao Ha 1

Myadestes obscurus

74.2 Kamao ?Ha 7

Myadestes myadestinus

74.3 Puaiohi Ha 7

Myadestes palmeri

74.4 Olomao Ha ?5 (no records since 1980)

Myadestes lanaiensis

75.8 Millerbird Ha 8

Acrocephalus familiaris

78.8 Elepaio Ha 1,6,7

Chasiempis sandwichensis

87.1 Maui Parrotbill Ha 2

Pseudonestor xanthophrys

87.2 Akikiki Ha 7

Oreomystis bairdi

87.3 Hawaii Creeper Ha 1

Oreomystis mana

87.4 Maui Alauahio Ha 2

Paroreomyza montana

87.5 Akepa Ha 1,?2

Loxops coccineus

87.6 Akekee Ha 7

Loxops caeruleirostris

87.7 Iiwi Ha 1,2,5,?6,?7

Vestiaria coccinea

87.8 Akohekohe Ha 2,?5

Palmeria dolei

87.9 Apapane Ha 1,2,4–7

Himatione sanguinea

87.10 Poo-Uli Ha ?2

Melamprosops phaeosoma

88.1 Laysan Finch Ha 13,16

Telespiza cantans

88.2 Nihoa Finch Ha 8

Telespiza ultima

88.3 Ou Ha 1

Psittirostra psittacea

88.4 Palila Ha 1

Loxioides bailleui

88.5 Nukupuu Ha (extinct?)

Hemignathus lucidus

88.6 Akiapolaau Ha 1

Hemignathus munroi

88.7 Anianiau Ha 7

Magumma parva

88.8 Oahu Amakihi Ha 6

Hemignathus flavus

88.9 Hawaii Amakihi Ha 1,2,5

Hemignathus virens

88.10 Kauai Amakihi Ha 7

Hemignathus kauaiensis

95.7 Hawaiian Crow Ha 1

Corvus hawaiiensis

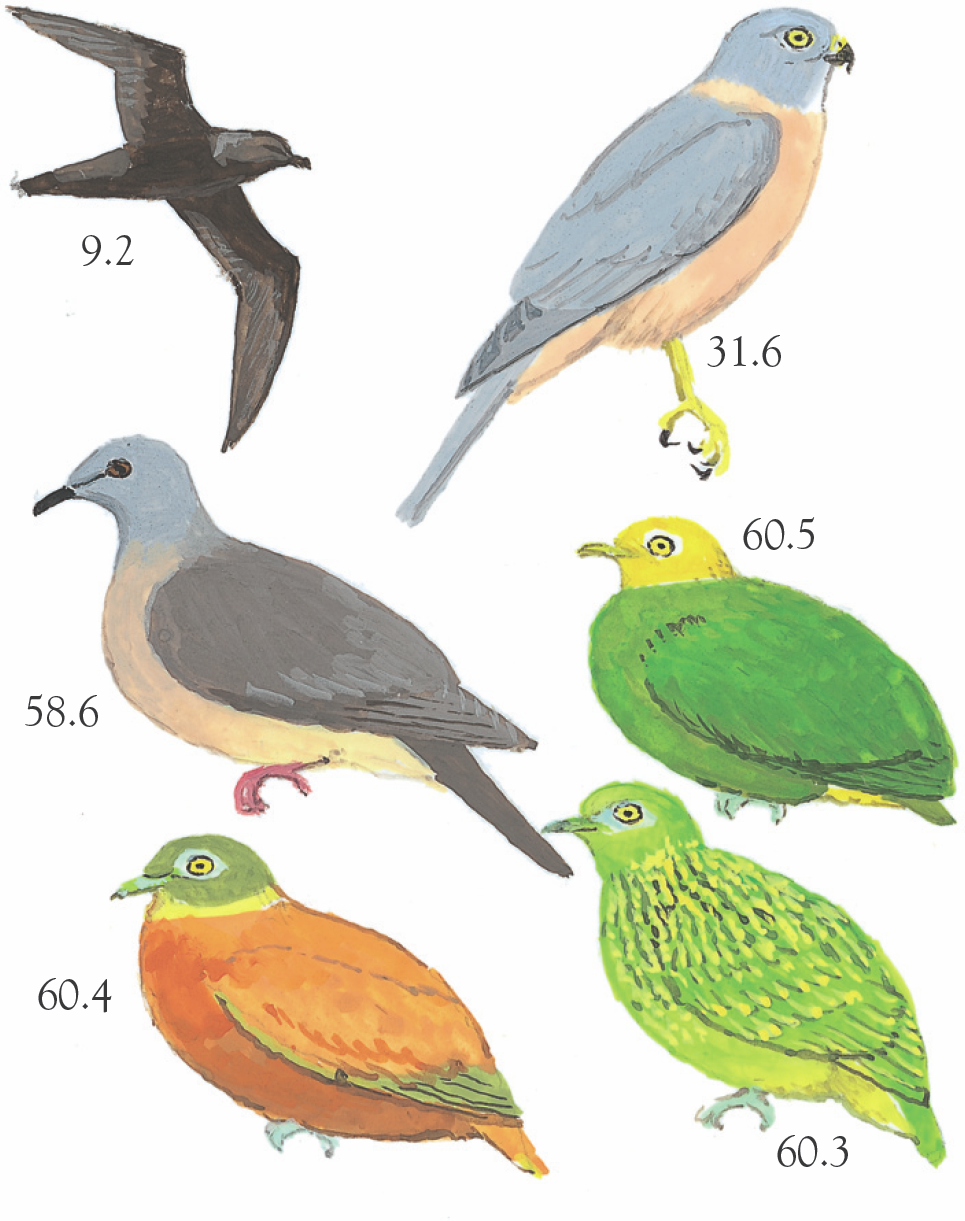

Fiji Endemics

149 species, incl the following 28 endemics:

9.2 Fiji Petrel Fi 10

Pterodroma macgillivrayi

31.6 Fiji Goshawk Fi thr., excl. 7

Accipiter rufitorques

58.6 Peale’s Imperial-Pigeon Fi all main Is.

Ducula latrans

60.3 Golden Dove Fi 1,9–11,14

Ptilinopus luteovirens

60.4 Orange Dove Fi 2,4,8,16,18,22

Ptilinopus victor

60.5 Velvet Dove Fi 3,15

Ptilinopus layardi

61.2 Crimson Shining-Parrot Fi 1,3,15

Prosopeia splendens

61.3 Red Shining-Parrot Fi 2,4,10,16–18

Prosopeia tabuensis

61.4 Masked Shining-Parrot Fi 1

Prosopeia personata

62.1 Collared Lory Fi thr., excl. S 7

Phigys solitarius

62.3 Red-Throated Lorikeet Fi 1,2,4,11

Charmosyna amabilis

74.8 Long-Legged Warbler Fi 1,2

Trichocichla rufa

75.3 Fiji Bush-Warbler Fi 1–4

Cettia ruficapilla

77.9 Black-Throated Shrikebill Fi 1–4,11

Clytorhynchus nigrogularis

78.6 Ogea Monarch Fi 23,24

Mayrornis versicolor

78.7 Slaty Monarch Fi thr.

Mayrornis lessoni

79.5 Vanikoro Flycatcher Fi thr.

Myiagra vanikorensis

79.7 Blue-Crested Flycatcher Fi 1,2,4

Myiagra azureocapilla

80.5 Kandavu Fantail Fi 3,15

Rhipidura personata

80.9 Silktail Fi 2,4

Lamprolia victoriae

81.6 Fiji Woodswallow Fi 1,2,4,6,11,16

Artamus mentalis

83.2 Layard’s White-Eye Fi 1–4,11

Zosterops explorator

86.3 Rotuma Myzomela Fi 21

Myzomela chermesina

86.4 Orange-Breasted Myzomela

Myzomela jugularis Fi thr., excl. 21

86.6 Kandavu Honeyeater Fi 3

Xanthotis provocator

86.9 Giant Honeyeater Fi 1,2,4

Gymnomyza viridis

91.7 Pink-Billed Parrotfinch Fi 1