Полная версия

Britain in the Middle Ages: An Archaeological History

Archaeology often seems to advance in fits and starts. First there will be a period of major reassessment brought about by new discoveries, then things will calm down while people consider the implications of what has just happened. Sometimes there is then a long period of stability – some would call it complacency – when every new discovery is seen to support the status quo. Finally the first hints begin to appear that all might not be as it seems – and the whole cycle starts again. These major changes in outlook and interpretation (theorists refer to them as ‘paradigm shifts’) tend to happen one by one in the different sub-disciplines of the subject. Thus prehistory today is just recovering from a major change of direction when straightforward functional interpretations, often based around economics, gave way to so-called ‘post-modern’ approaches, which placed symbolism and ceremony at the heart of ancient culture.

A big change in direction has just happened in the world of early medieval studies, and we now find ourselves at the second stage, when the implications of what has happened are being considered. As often occurs in archaeology, the shift in thought appears at first to have been triggered by new discoveries – in this instance thousands of metal finds, many of them coins – but the new information has come at the right time to support a radical new view of Europe in earliest medieval times.

The principal exponent of the new approach is Michael McCormick, Professor of History at Harvard University, whose huge new book will take most people some time to assimilate.14I won’t attempt a summary of its 1,101 pages, but some of his conclusions are directly relevant to our story. We will shortly be discussing trade in greater detail, but to understand what was going on we have to look at the bigger picture, because trade cannot take place in a vacuum. People trade with each other not just because they need what others can supply, but because they have the means to do so and have established reliable lines of communication. Trade and communication are inextricably linked. Professor McCormick has shown that sometimes the communication can take place over very long distances indeed.

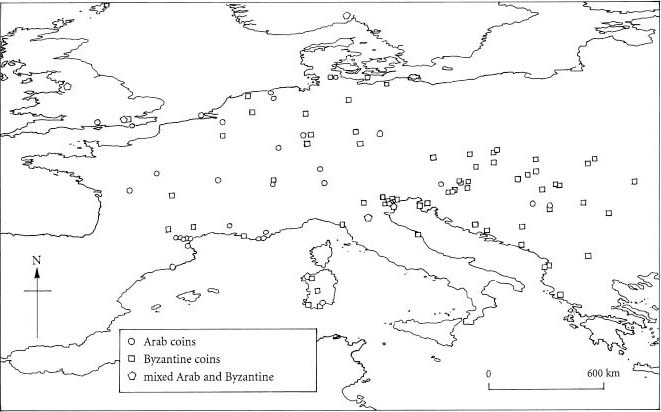

McCormick’s reconstruction of trade in the fourth to the ninth centuries is based on a number of sources, but especially on an exhaustive study of Mediterranean travellers’ records, findspots of Arab and Byzantine coins, and ship movements in the Mediterranean Sea, which in turn are based on contemporary records such as customs registers. These sources have provided a huge amount of information on the way that people and ships moved around Europe, and McCormick fully acknowledges that many Arabic records have yet to be tapped.

Europeans have a tendency to regard Europe as the wellhead from which all culture springs, following the flowering of Classical Greece in the fifth and sixth centuries BC. The modern concept of ‘the West’ is of a culture which is entirely European and essentially self-generated. The one or two acknowledged non-European influences, such as Christianity, are the exceptions that prove the rule. This Europe-centred world view is dangerously flawed, one-sided and misleading. Currently the Muslim world is seen by some as being in direct opposition to the West. It is viewed as having different attitudes to democracy, women’s rights and the relationship of Church and state. Laying aside the validity or otherwise of these modern perceptions, it might be helpful to show how the early flowering of culture and science in the rapidly expanding Muslim world played a significant role in fostering the development of early medieval Europe. The cultural traffic has by no means been in one direction only. But first, some essential dates and facts.

The Prophet Mohammed (the name means ‘praised’ in Arabic) was born sometime around 570 and died in 632. The Muslim or Arab Empire expanded rapidly between the year of the Prophet’s death and 650.15 From the mid-seventh to the mid-eighth century this vast empire was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty from their capital in Damascus, Syria. They were considered impious and tyrannical by many – especially in Iraq – and were replaced in 750 by the Abbasids, whose capital was in Baghdad. The Abbasids claimed direct descent from the Prophet, via his uncle Abbas. The Shi’ites disputed this claim, holding that true direct descent could only be via the Prophet’s daughter Fatima and her husband Ali.

FIG 4 Distribution of Arab and Byzantine coins in Carolingian (750–900) Europe. Some of the findspots contained more than one coin. The findspot in north-west England is the Viking hoard from Cuerdale, Lancashire, which included many Arab and Byzantine coins.

The sheer scale of the cities of the early Islamic Empire dwarfs anything in contemporary Europe. We still do not know the precise size of Baghdad under the Abbasids, because no accurate survey exists, but it was probably in the order of seventy square kilometres.16 Their royal city at Samarra, 125 kilometres north of Baghdad, has been described by Alastair Northedge as the largest archaeological site in the world. It was built and occupied for less than a century, yet its streets and houses covered a staggering fifty-eight square kilometres after only twenty years. Although now entirely deserted, it is still visible from the air, where mile after mile of carefully-laid-out gridiron streets can clearly be seen. Within the city were hunting reserves, racecourses and gardens. There were also numerous palaces, one of which was approached by a massive processional way, perhaps resembling The Mall in London.

The rulers of the Muslim world were known as caliphs (from the Arabic khalifa: ‘deputy of God’), and the caliphate of the great Abbasid, Harun al-Rashid, who ruled from 786 to 809, and who features in the Arabian Nights, was truly vast. It extended from modern Tunisia through Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Iran and what was once Soviet Central Asia. Oman, Yemen and much of Pakistan were also within his power. This great empire was no flash in the pan. Harun’s capital Baghdad was the largest city in the known world, and spread for miles on either bank of the Tigris. By this time the early internal conflicts within the Muslim Empire had been resolved. We know that Harun was in contact with Charlemagne, because he gave him, among other things, a superb and highly decorated enamel water jug on the latter’s coronation by the Pope in Rome in the year 800. During this time the Caliphate and Byzantium were in almost permanent conflict. Harun’s son, al-Ma’mun, who eventually succeeded him and ruled from 813 to 833, was an enlightened ruler, a great builder and supporter of science and the arts. But following Harun’s death, Baghdad and the Caliphate began to be plagued by civil war. Baghdad itself eventually fell to Shi’ite attacks in the mid-tenth century.

McCormick (following the work of earlier Belgian historians) has shown that trading contacts with the thriving economic, cultural and scientific world of the Caliphate played an important part in the development of Europe, most of which was under the control of Charlemagne’s Carolingian Empire (about 750–900). It was contact with the Caliphate and Byzantium (once the eastern Roman Empire) that helped to kick-start early medieval Europe following the disruption caused by the collapse of the western Roman Empire. Westerners tend to think of the Carolingian Empire as huge and magnificent, but it would have appeared less significant and perhaps somewhat peripheral to someone like Caliph Harun. It was the Carolingian Empire which ultimately fuelled the growing trade around the southern North Sea.

Slaves, many of them from Britain and mostly captured on military campaigns, were the principal ‘commodity’ exported to the Arab Empire. The trade had been very brisk between 650 and 750, but received a boost when sometime around 750 the Caliphate suffered an attack of bubonic plague. European traders from Venice, Byzantium and the Carolingian Empire filled the gap in the Arab labour market. The scale of this trade was truly remarkable:

The last five decades of the eighth century were also the era when the Carolingian conquests could well have flooded the market … through the capture of large numbers of war slaves … As the slaves flowed out in these final decades of the eighth century, Arab coins, eastern silks, new Arab drugs, and old eastern spices surged into Italy. The slave market fuelled the expansion of commerce between Europe and the Muslim world.17

The new vision of early medieval Europe differs profoundly from the existing ‘conventional wisdom’. As McCormick puts it, this is a Europe

which is not the impoverished, inward-looking, and economically stagnant place many of us learned about in our student days. On the contrary, in its origins, Europe’s small worlds came to be linked to the greater world of Muslim economies … These links were perhaps more modest compared with what had once existed [in Roman times] and with what would develop … but they were real and, in economic terms, they counted, especially given Europe’s small scale.18

He goes on to point out that trade brings with it cultural contact, and that at the time Arab science was far ahead of anything happening in Europe. The trading contacts were also with Byzantium, which was not then the sealed-off world within the walls of Constantinople that it was later to become. McCormick sees early medieval Europe as more culturally open than at any other time in its history, before and in all probability since. We know that Charlemagne would have been acquainted with Franks, Anglo-Saxons, Danes, Lombards and Visigoths, but McCormick points out that he would also have had Venetians, Arabs, Jews, Byzantines and Slavs among his many contacts. It is thus surely not completely absurd to imagine an Arab or Venetian merchant walking through the streets of Lundenwic, as London was then known.

How did this flowering of early medieval trade affect life in Middle Saxon England? To find the answer we have to consider the origins of the first towns, because these were the safe places in which trade could take place. I will discuss the flourishing of Later Saxon towns in Chapter 4. Here I am concerned with the origins and roots of urbanism. Put simply: how and why did towns develop? What was the wider economic picture that encouraged their growth? Had I been asked those questions twenty years ago, I would probably have replied with a stock anthropological answer – as befits a prehistorian. I would have said that elites in various communities were competing with one another to control certain key natural resources such as salt, water, ores or productive land. But in the last two decades simple ideas such as this have been blown out of the water by a mass of new information. What sparked, and continues to fuel, controversy within the profession is that this new information was produced by hobby metal detectorists. These people are non-academics, and almost every archaeologist’s Aunt Sally. But are they wholly evil? I think not. Far from it, in fact.

Even so, I have to admit I am not happy about metal detecting. In archaeological terms it is fundamentally wrong to wrest objects out of their contexts for personal gain. Responsible metal detectorists might reply, with justification, that often they donate their best objects to museums, and that in any case the ‘context’ from which they removed their finds had usually been eradicated by intensive modern agriculture. That may be true, but for every responsible metal detectorist there are others who prefer to conduct their hobby less openly. I was president of a local detectorists’ club in the 1980s, and I well recall that our weekly meetings were attended by two or three dealers in antiquities who often had extended ‘conversations’ with club members in the car park.

In the 1980s metal detecting grew rapidly in popularity. Even if they had wanted to – and many did – archaeologists would never have been able to make the hobby vanish. It was clear that it could never be banned, because the law could not possibly be enforced: detectorists would be driven underground, and if that happened, any chances of monitoring what they were finding would disappear. As it is, it’s hard enough to prevent dedicated illegal ‘nighthawks’ from detecting over legally Scheduled Ancient Monuments (sites of national importance granted statutory protection).

While the attitude of most archaeologists in the early 1980s was hardening, one exceptional and farsighted individual, Tony Gregory, began to work with detectorist clubs in Norfolk. Pretty well single-handed he started to change archaeological attitudes. He was a close friend of mine (sadly he died in 1991 of cancer), and I spent several smoky evenings upstairs in Norfolk pubs while club members showed him their latest finds and he made notes of where they had been found. As he pointed out, it was bad enough that the finds were being removed in the first place, but it was an archaeological catastrophe that their findspots were being lost too. Those findspots are archaeologically every bit as important as the objects themselves.

Eventually the government bowed to archaeological pressure to regulate what was going on. In 1997 it sponsored the Portable Antiquities Scheme, which exists to ensure that findspots are recorded and major new finds are saved for the nation.19 This work is carried out by regional FLOs, or Finds Liaison Officers, who have the tricky task of retaining the trust of both archaeologists and detectorists. Even despite the Portable Antiquities Scheme, I still find the haphazard removal of finds from their contexts a very difficult moral dilemma, and one made no simpler to resolve by the outstandingly important new information that has recently begun to emerge.

This new information is transforming our understanding of trade and exchange in northern Europe between the seventh and tenth centuries, and it is doing this by means of so-called ‘productive’ sites. The term was coined (pun unintended) by numismatists, and would never have been chosen by archaeologists, who might have dubbed them ‘rich’ or ‘significant’ sites. To me, ‘productive’ is a word one might attach to an oil well. That quibble aside, ‘productive’ sites have turned the world of Middle Saxon archaeology upside down – with more than a little help from some distinguished specialists in ancient coinage.20

The four hundred years between 600 and 1000 (the seventh to eleventh centuries) are now seen to have been a period of economic renewal following two centuries when northern Europe was searching for new identities and direction, following the demise of the official Roman Empire in the west. I say ‘official’ because some form of Romanised authority did continue, but it had now been devolved to local and regional government. The Church, which had become the favoured religion of the Roman Empire under Constantine from AD 324, also played an important role in maintaining such government during a period which archaeologists and historians now refer to as Late Antiquity.

The new economic order seems to have been arranged around a series of major commercial centres, known as emporia in Latin and wics in Anglo-Saxon or Early English. Finds from the emporia in Britain and on the Continent are characterised by their richness and range. Most importantly they provide clear and unambiguous evidence for long-distance trade. These sites sprang up quite rapidly around the coasts of northern Europe, and their arrival coincided with the appearance of a widely adopted silver coinage which became the common currency for the emerging states around the shores of the North Sea. The importance of the emporia has been recognised for some time, and it was believed that they came into existence in the earlier seventh century as seasonally occupied trading centres, operated by independent merchants who worked outside aristocratic or elite control.21 It was believed that from about the 670s they began to come under such control. But following discoveries such as the magnificent burial at Prittlewell (AD 650) at the emporium or wic of Ipswich, we now realise that these places were probably under royal or elite control from the outset. That is not to say, however, that they were not also well integrated into the local economy, or that specialist traders were not also involved. They almost certainly were.

The emporium system was essentially elite-driven: it was all about power, prestige and display in the highest echelons of society. We now understand that while such motives were undoubtedly significant, many more people were involved, and it has become possible to see the whole process in far broader terms. It is becoming clear that the emporia formed the pinnacles of an integrated trading system that was united not just by ships and the sea, but by the network of good roads that had been established by the Romans, and had never been completely abandoned.

The true significance of ‘productive’ sites has only slowly filtered into the academic literature, largely because the realms of academia and metal detecting rarely come into contact. Archaeologists and numismatists are rather better at making such contacts, so the new discoveries have gradually been surfacing in journals and websites devoted to those particular interests. As the information is largely derived from metal detectors it is biased in favour of non-ferrous finds, because most of the machines used today have a discriminator function which allows iron to be screened out. The reason is that the modern ploughsoil is richly scattered with millions of old nails, many of them derived from the ash of scrap timbers burnt on farmyard muckheaps to add potash to the manure. Signals from these nails tended to drown out other signals in the metal detectorist’s headphones. Iron nails, it must also be said, are of no commercial value. So all iron finds, and usually non-metal finds too, such as pottery, tend to be ignored, thereby biasing the information enormously. Were archaeologists to excavate and metal detect ‘productive’ sites, they would plot and keep everything.

This mass of new information is appearing not just in England, but in Europe too. Places like Holland and Denmark have decided to cooperate with the detectorists, and as a result information is flooding in. Elsewhere, however, in Germany, France and Italy, for example, the hobby is still illegal, so new discoveries in these countries are happening very much more slowly, and through traditional means, such as official excavation. We know that illegal finds from these countries are entering the black market. We also know that some are being given false provenances in countries where detecting is less frowned upon.

It is becoming clear to numismatists working with this new material that there was something approaching an explosion of coin-making around AD 700. To give some idea of its scale, the volume of money then in circulation in southern England was not to be paralleled until the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. The situation in Britain was mirrored on the Continent, and it is now quite clear that the ‘explosion’ in currency production represents a sudden increase in trade across large parts of northern Europe.

There is good evidence to suggest that the coins from ‘productive’ sites were still more or less in situ when the detectorists found them. This would suggest that at such sites coin-loss equates with coin-use. In other words, we can safely assume that the coins were mislaid during trade, and were not placed in the ground as offerings, or concealed in hoards for safekeeping in times of strife. This assumption is based on the distribution of finds from ‘productive’ sites, which are spread across the landscape and do not occur in small, tight clusters. Numismatists have shown, moreover, that the coins found on one site reflect those from others. Changes in currency tended to happen across regions, which again suggests trade rather than hoarding and burial (often hoards contain antique or outdated coins kept purely for the value of the gold or silver they contain).

Analysis of the coin finds from ‘productive’ sites and other smaller ‘hot spots’ is still at an early stage, and so far no new mints have been identified, but we can be reasonably sure that the patterns revealed in these new and very early distributions are ‘real’ – in the sense that they reflect ancient trade. One example will suffice. Detectorists have discovered an isolated ‘hot spot’ of late-seventh-century Early Saxon coins, known as ‘primary porcupine sceattas’,* in the upper Thames Valley. We know from other evidence, including coinage, that this was to be an important area for the production of wool, starting in the mid-eighth century. The new ‘hot spot’ suggests not only that the wool trade in the chalklands of this region was under way much earlier, but that it began less gradually than was previously supposed.

It would be a mistake to view trade in early medieval Europe as being part of a free market economy, any more than it was in the Bronze Age. In the past, just as in certain parts of the world today, trade was controlled or encouraged by influences other than purely market forces. Usually these non-market forces represented figures or centres of power within the structure of the state, such as kings, landowning nobles, military leaders and, increasingly, the Church. Protectionism – in the sense of the protection of vested interests – is not just a modern phenomenon. Having said that, the evidence provided by emporia and ‘productive’ sites does strongly indicate that genuine trade did take place within the contexts of a rapidly developing political structure. The question that has to be asked is, to what extent did these power politics affect the growth and development of early medieval commerce?

Two recent studies have suggested that royal power was used both in the Baltic area and in Rouen to influence the arrangement and location of the trading quarters in major emporia.22 In the Baltic example the Danish King Godfred relocated all the merchants from the original settlement to one over 130 kilometres distant in the early ninth century. In the French example an essentially organic trading landscape of ports and trading posts, many of them owned and run by monasteries, was centralised by royal authority, reacting to increasing Viking raids, around Rouen, which then became an important urban centre, but one very much under royal control. In neither instance was trade discouraged by these changes.

Studies of eighth-century coin distributions suggest that trade within the various regions of northern Europe was tightly-knit and integrated. There were consistent patterns that developed over time and space. There does not seem to be evidence (yet) for currency stopping short at national boundaries. Although we know that the process of state formation was under way at this time, there is as yet no evidence that this was impeding or adversely affecting the development of wider patterns of trade.

The relatively recent recognition of ‘productive’ sites, ‘hot spots’ and other smaller centres within the hinterland of the major emporia does raise the question of the extent to which non-royal patronage and influence could affect the day-to-day business of trade in such places. It seems inherently unlikely that the hand of royalty extended to these more remote and distant places. So did these places develop as a result of simple private enterprise? The general consensus, while acknowledging that individuals and individual motives undoubtedly played a significant role, prefers to see the Church as the engine or inspiration for these smaller centres of trade. Some of the English ‘productive’ sites in Suffolk, Norfolk and the Isle of Wight were located at or near former ecclesiastical sites, and for others in, for example, East Anglia, the change was the other way around, with seventh- and eighth-century ‘productive’ sites acquiring a religious dimension by the eleventh century. There is other evidence too that the Church played an important part in the growing economies of southern Britain in the eighth and ninth centuries.