Полная версия

Britain in the Middle Ages: An Archaeological History

It is also worth noting that the impact of the Black Death in 1348 was so devastating that the southern British population could not have retained any vestiges of immunity from earlier infections. In other words they must have been completely free from it – and for several generations. It seems to me that the plagues Bede writes about are unlikely to have wiped out whole swathes of the British population, thereby releasing land for huge numbers of people from across the North Sea to settle on. It is, however, entirely possible that plague in the seventh century could have played a role in freeing the survivors from restrictive ties and obligations.2 Just as we will see in the four-teenth century, the greater availability of land ultimately led to prosperity – which was such a feature of southern Britain in the Middle Saxon period.

For these and other reasons I suggested in Britain AD that the Anglo-Saxon invasion was more a spread of ideas than of actual people, as there is no convincing archaeological evidence for war cemeteries or for David Starkey’s ‘ethnic cleansing’. In a few decades I feel sure that genetics will be able to sort the problem out, one way or another. If it is indeed found that wholesale population replacement did take place, the challenge to archaeologists will be to work out how this could have happened. What was the social mechanism that enabled such a huge ethnic transformation to occur without, it would seem, major social disruption and conflict?

Maybe we can learn something here from the story of the Vikings, who were successful invaders, but who also seemed hell-bent not so much on rape and pillage (which certainly happened) but on settling down and becoming English peasant farmers. The Viking army, however, left clear and unambiguous documentary and archaeological evidence for warfare – something which is still lacking in the archaeological record of the Dark Ages. Perhaps some other, more subtle and archaeologically undetectable, process was at work in Early Saxon times. Maybe strict new codes of marriage introduced by the arriving Anglo-Saxons prevented native British women from having children; maybe too there was some other form of eugenic apartheid. As yet we simply don’t know, but one day we might find out. Either way, it will require some creative thought.

In Britain AD I also discussed the events that led up to the Synod of Whitby (AD 664), at which it was decided that the future of England lay with the Roman rather than the Celtic Church. From a very long-term perspective this was a most important decision, because it ensured that thenceforward British intellectual and spiritual attention would be directed towards Europe. The medieval period was also a time when the authority of the Church played a central role in most aspects of the life of the nation. Before Whitby the Church was altogether more fragmented, and its growth more organic. After Whitby it became both more centralising and more institutional, and soon became a significant power in the land. The increasing importance of the Church also promoted literacy and gave rise to a greater and more widespread use of written documents.

By the early seventh century the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of what was later to be England were beginning to emerge, and we know of a series of very rich or ‘royal’ burials at places such as Sutton Hoo, Taplow and Prittlewell. I described these graves in Britain AD, and I will not repeat myself here, other than to say that these lavish finds show that society was clearly becoming increasingly hierarchical, and that powerful ruling elites had begun to emerge.3 By the end of the Early Saxon period Christianity was of growing importance, as is well illustrated at Prittlewell (AD 650), where an otherwise pagan chamber burial, with roots that can be traced back to the pre-Roman Iron Age, had been ‘Christianised’ by the addition of two gold foil crosses.

The documentary evidence for Middle Saxon England is much better than that for Early Saxon times. Among the sources available to us, two stand out. The first has to be the work of that great genius of northern Britain, the Venerable Bede, who wrote his Ecclesiastical History of the English People in 731. But there is also a most remarkable eleventh-century source, a tax assessment known as the Tribal Hidage. This document gives us an important glimpse into the earliest geography of England, and I will consider it further in Chapter 3, when we come to discuss the development of administrative units such as the shires.

I mentioned Brian Hope-Taylor in my Introduction. His remarkable excavations at Yeavering in Northumberland transformed our knowledge of Earlier Saxon high-status architecture. His work has given us a vivid picture of life within a royal household in northern Britain prior to the onset of Viking raids. Strictly speaking, Yeavering was in use in the decades just before 650, the notional start of the Middle Saxon period, but dates such as these are for convenience only – and it is convenient for me to ignore them now. First I want briefly to discuss life in Britain north of, say, Yorkshire. Then we will turn our attention further south. The contrast between the two regions will help explain the phenomenon that has come to be known as the Vikings.

It is strange how certain bits and pieces of what you learned at school or university stay with you in later life. Sometimes these half-remembered fragments are of little consequence: does it really matter, for example, that one could have walked across the North Sea 12,000 years ago? Although I was quite interested in the archaeology of early medieval Britain, I never really got to grips with what was happening in the north of the island, except to marvel over the illuminated pages of that superb masterpiece in the British Museum, the Lindisfarne Gospels. This came to the museum in 1753 as part of its ‘Foundation collections’, which also included the only copy of that remarkable Anglo-Saxon epic poem, Beowulf..4

Before Brian Hope-Taylor’s excavations and the great growth in Scottish and northern archaeology that has happened since, the main sources of information on early medieval Britain were carved stone crosses, inscriptions, and of course those superb illuminated manuscripts. Their rich decoration owed much to various influences from within Britain, and the style has come to be known as the ‘insular tradition’. Here the term ‘insular’ is not meant to be pejorative; it simply signifies that the manuscripts produced on the island of Britain were quite distinct from those being produced elsewhere in Europe. They were also just as good as, or even better than, anything on the Continent. Besides the Lindisfarne Gospels there are two other famous examples, the Books of Durrow and of Kells (both in the Library of Trinity College, Dublin).5 All three are Gospels and are particularly renowned for their intricate ‘carpet pages’ of elaborate interlaced design whose vivid 3-D effects would actually make them lethal if woven into floor coverings. The spirit behind the restless movement of this work recalls, for me at least, the unquiet world of pre-Roman, so-called ‘Celtic’ Art. There is little here of the Roman Church, or indeed of Roman culture.

The suggestion of ‘Celtic’ influences summons up images of Ireland, but one should not be misled into thinking that the insular tradition was about Ireland, or those Irish settlers in Scotland, the Scotti, alone. English, or rather Anglo-Saxon, influences were also very important contributors to this rather heady graphic cocktail. We saw in Britain AD how there is growing evidence for mobility in Anglo-Saxon England, and the same can be said for the lands around the western seaways.6 The art of the insular tradition is clearly a fusion of both English (Anglo-Saxon) and British traditions, but its great flowering was sometime after the Synod of Whitby. The Book of Durrow and the Lindisfarne Gospels are probably mid-seventh century, and Kells is slightly later (late eighth). It may have been the stability provided by the new post-Whitby political and ecclesiastical regime that provided the environment for the new style to emerge and flower. One is tempted to reflect that it is far easier to alter the outward form of religious rituals than the feelings and emotions that lie behind them.

At college we learned in some detail about the glories of these three great works. I also remember seeing the Book of Kells as a small boy when I was taken by one of my Irish uncles, Esmonde, to the library of Trinity College, Dublin, where he himself had been a student. Esmonde was to become a historian of Hitler’s pre-war policy at London University, but at that stage his life in Dublin was rather wild and included some very colourful friends, like the playwright Brendan Behan. Esmonde taught me by example that the past was far too important to be taken too seriously. In the drab days of the 1950s those huge, colourful pages, glinting with gold, made a lasting impression on me. The Book of Kells features large animals, strange beasts and the huge-eyed faces of biblical characters such as the Gospel writers. It has always been among my favourite works of art.7

One might suppose that such great art was produced in a well-endowed culture where people had the time and resources to lavish upon such things. Indeed, that was how life in northern Britain was seen when I first learned about the Celtic Church. Brian Hope-Taylor’s excavations at Yeavering, if anything, reinforced this view of a heroic age that could still find the time to encourage the contemplative life of men such as Bede, or the masters who created the great illuminated manuscripts. That term ‘heroic age’ says it all. But what does it really mean?

The best answer I have come across has been provided by the greatest scholar of northern Britain in early medieval times, Professor Leslie Alcock, who has just published a magisterial review of his subject.8 Alcock makes it clear that this was indeed a heroic age in which great feats of valour on the battlefield were celebrated in verse and song; but there was more to it than just fighting. Many sources refer to scenes from the life of Christ, and it is apparent that the essentially pagan ideals of the heroic age were transferred to Christian beliefs. The ideals of a warrior elite were tempered by the humanity of those who, like Bede, opted for the quieter life of the soul.

The political situation in what is now northern England in the seventh – ninth centuries was extremely unstable. This is remarkable, because the eighth century saw what has been called a Northumbrian Renaissance, epitomised by scholars such as Bede and religious houses such as Lindisfarne. To the north and east, occupying the land in England and Scotland around the Cheviot Hills, was the kingdom of Bernicia, with Deira to the south, centred around the fertile Vale of York. Deira was taken over by Bernicia in the mid-seventh century, and both were then subsumed within the large kingdom of Northumbria, whose borders fluctuated quite widely, especially when campaigns against its northern neighbours took a turn for the worse. Southwestern Scotland was occupied by the Scots (or Scotti in Latin), who were in fact settlers from Ireland. North of the Firth of Tay were the Picts. During the heroic age much of the warfare took place between Angles from Bernicia and the Picts or the Scots further north.

Yeavering is about as far north in what is now England as it is possible to go. It is located in the Cheviot Hills, at the heart of Bernicia, just below a prehistoric hillfort known as Yeavering Bell. If you struggle over the ramparts of this hillfort in late winter, when the rough grass is low, you can clearly see the circular outline of collapsed Iron Age roundhouses. The settlement is on gently sloping ground at the foot of Yeavering Bell, whose commanding presence is everywhere, and which must have been the principal reason why the site was selected as a royal centre. The inhabitants of Yeavering could claim descent and protection from the ancestral figures who constructed the great hillfort.

This Bernician royal settlement – and I use that loaded word advisedly – went through a number of different phases. Great timber halls appear, are modified and replaced. Cemeteries even grow, come and go. But throughout its development the site shows the clearest signs of organisation and thought. Alignments matter, and symbolism is significant. Sometimes as I read Brian Hope-Taylor’s report – which I still consider the finest excavation report produced by a field archaeologist working in Britain – I feel I am in the Bronze Age, where sites like Stonehenge were about alignments almost more than anything else. Just as the presence of the nearby hillfort had a political message, alignment on celestial phenomena such as solsticial sunrise (or sunset) was a way of linking the world of the living to the power and authority of another world. These things mattered in the Bronze Age, as in Saxon times – as indeed they do today. Ceremony and ritual are methods that society uses to confer special authority on those selected (by whatever means) to rule.

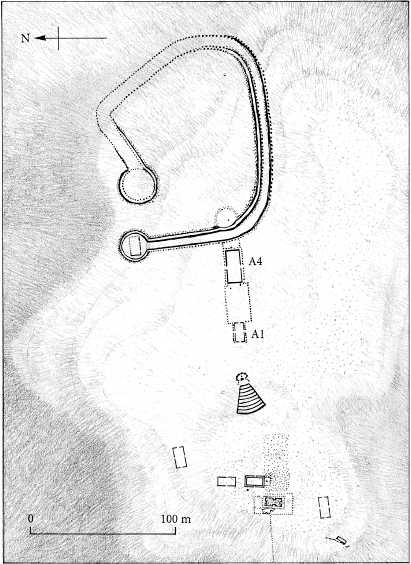

FIG 2 The Bernician royal settlement at Yeavering, Northumberland, at its climax in Phase III, in the 620s. Six timber halls and a kitchen building lie to the east of the Great Enclosure, an elaborately defended meeting place, with two circular entranceworks, one of which contained a timber hall. At the centre of the settlement is a tiered timber grandstand or viewing platform where public ceremonies would have taken place. The large hall A4 and the smaller building A1 were joined together by a post-built yard or enclosure..

Hope-Taylor was able to distinguish five phases of post-Roman occupation at Yeavering, of which the most elaborate was Phase III. This phase ended with a catastrophic fire which the excavator attributed to hostile action. I’m not certain that the evidence he cites is absolutely convincing, because timber and thatched buildings can burn like tinder in exposed situations. All it takes is a spark on a dry roof on a breezy day – or night. But if the fire was indeed caused by hostile action, it is likely to have been a British rather than a Viking raiding party, as Viking raids had yet to get under way. Leslie Alcock has reassessed Hope-Taylor’s dating and is unable to link the great fire to any known historical event. Taking the evidence together, he suggests that the most elaborate and extensive phase (III) of occupation happened in the 620s. The later two phases (IV and V) may have continued into the 640s.9

Just to the east of the settlement was the Great Enclosure, with two circular entranceworks, one of which contained a hall. The enclosure is a massive affair, perhaps resembling a lowland hillfort, and was surrounded by two ditches and two sets of triple palisades of posts. This has to be seen as a fortification of some sort, but at the same time it does seem strange that the largest halls were positioned outside it. I think we are looking here at some form of gathering place that was meant to instil confidence in those who met there. Maybe it was a marketplace that was given royal protection – and the elaborate defences were also a way of reminding people that they were only able to trade there safely thanks to a powerful ruler.

In post-Roman Phase III the settlement consisted of at least six rectangular timber halls, one of which, Hall A4, was truly huge: 80 x 37 feet (24.4 x 11.3 metres); this gives a floor area of 3,000 square feet (275 square metres) – the largest known hall of the Saxon period. The settlement also included a cemetery and a unique timber grandstand or viewing platform. Hope-Taylor suggests that the shape of this structure would fit with the focus being on some sort of throne. The curved wall to the rear of the possible throne would have helped to project the voice of anyone addressing the audience from it. Perhaps a single post behind the throne carried some sort of royal standard or emblem.

The buildings at Yeavering were grand in the extreme, but the finds from the site were strangely unexciting, comprising perhaps two or three boxes of locally made pottery, a handful of coins, clay loom-weights, some metalwork and a quite a few iron nails. Compared to the ‘productive’ sites of Middle Saxon southern Britain, which I will discuss shortly, this is a less than lavish collection of material. The underlying concept of what constitutes royal pomp, or panoply, at Yeavering contrasts hugely with what we know about contemporary sites in the south, at places like Sutton Hoo in Suffolk, where the ship-grave of King Raedwald of Essex (who died in AD 625) contained treasures from all over Europe and the Mediterranean world. Yeavering seems to be more introspective, to be about impressing people with grand buildings and awe-inspiring structures rather than with wealth pure and simple. It also suggests that the royal house of Bernicia was probably more concerned with local relationships and hostilities than with long-distance trade. Again, this attitude to political life is markedly at variance with what was happening further south – and indeed with what was happening, and was about to happen, in monasteries in the north, at places like Lindisfarne, Jarrow and Monkwearmouth, where those masterpiece manuscripts of the ‘insular school’ were to be created.

Yeavering was not unique in its large timber halls. Other early examples have been found across Northumbria (there are a dozen at Thirlings) and in southern Britain, at sites like South Cadbury in Somerset and West Stow in Suffolk, which I will discuss further shortly.10 We know from sources such as Bede that these great halls were spaces where feasting and general carousing took place under the approving eye of the lord. But they were also about more than simple pleasure. They were places where justice was dispensed, and their arrangement was intended to show – display would perhaps be a better word – the lord and his family to good advantage. The guests were either the lord’s subjects or neighbouring nobility who attended his table as part of the continuing business of regional diplomatic relations. The great halls played an important part in the development of early medieval society in Britain.

The rarity of finds at Yeavering tends to be a feature of early medieval sites in northern and western Britain. Coins too tend to be rare, and it would seem that the economy was mainly based around barter. In situations such as this we should be careful of simply assuming that somehow coins = trade. In actual fact exotic coins can be collected as beautiful objects in their own right, they can be used as a way of storing wealth, and of course the royal name and portrait carried on many of them is a political statement in itself – and one which would only be seen by members of the upper echelons of society.

Throughout northern and western Britain there is evidence for trade with the Mediterranean region and Gaul. Usually this comes in the form of amphora fragments. Amphorae were large, robust vessels in which wine and oil were exported from the Mediterranean. Fine table wares were often made in north Africa. Coins do not appear to have been used in these transactions, and it is usually assumed that other items were exchanged, such as tin (in Cornwall) or copper, lead, silver or gold (elsewhere). Other items produced in north-western Britain probably included hides, fur and slaves. Wool and cloth do not seem to have been produced in exportable quantities.

Many sites, such as forts and rural settlements, echo Yeavering in revealing fine buildings but a rather small inventory of finds. One exception is the early Christian community at Whithorn Priory in south-west Scotland. This remarkable site has produced many fine buildings, which were accompanied by a large collection of pottery, glass and other objects.11 Many of these were imports. The site developed into a very significant settlement that has been described as proto-urban – not quite a town, but almost. The large numbers of finds might in part reflect the high quality of the excavation, but then Yeavering, to name just one example, was dug to equally high standards and produced little. One key to what might be special circumstances at Whithorn was provided by the distribution of the sixty-five coins, which mainly occurred around the church doorway. This could possibly suggest that there had been a church collection point of some sort here, and that the coins around it were mislaid offerings. However, it doesn’t explain how the people who made the offerings obtained their coins in the first place.

So if the coins at Whithorn cannot be linked directly to trade, what about the many imported Mediterranean, Gaulish and Continental objects? Surely these indicate extensive trade? In fact a close study of the various types of exotic pottery shows that they were actually imported rather sporadically and over quite a long period, from the late fifth to the eighth century. What was the nature of the trade between north-western Britain and elsewhere? Some would have taken place through Anglo-Saxon middlemen at places such as York, where we know that a coin mint had been established in the late seventh century. Some took place under the aegis and protection of the Church, as at Whithorn. But was there regular to-ing and fro-ing; was there continuous and active communication? On the whole I think not. Contacts had been established and could be called upon when needed, which is another way of saying that this was essentially a command economy.

Professor Charles Thomas has suggested that the trade between the Mediterranean region and his site at Tintagel Castle in north Cornwall would have involved ships which loaded up at various Mediterranean ports and then headed towards Britain, probably via the Spanish and Portuguese coast.12 Maybe this happened every few years, we cannot tell, but it was never the constant and increasingly active, coin-based trading network that we now realise existed around the southern North Sea basin from at least the later seventh century. That was something altogether different, and both north-western Britain and Ireland lay outside it.

In 1970 I briefly flirted with the idea of transferring my academic allegiance from prehistory to the Saxon period. There were several reasons for this. First and foremost, I suddenly felt daunted by the prospect of directing my first major excavation at Fengate, in Peterborough. This was already one of the best-known prehistoric sites in Britain, and its sheer complexity was very challenging. I also knew that the following spring I would have to turn talk into action, and like many young men I had been quite free in voicing my criticisms of the previous generation. Now I would have to prove whether or not I could dig as well as them – and secretly I knew that many of them had been very good indeed. Prehistory was also going through a rather complacent period; by contrast the archaeology of the Saxon period seemed very exciting. New discoveries were being made on an almost daily basis. It wasn’t just a matter of finding new sites and artefacts, but people were coming to grips with what seemed to be a wholly new world. In the 1950s the post-Roman centuries were seen as retrogressive, a return to barbarism and incompetence, but in the sixties and seventies this was reversed. It was realised that the Saxon landscape was not cloaked in forests of neglect. People did not live in muddy holes – so-called Grübenhaus ‘pit-dwellings’ – in the ground. Instead, new buildings, settlements and landscapes of great sophistication were being revealed. Vitally important excavations at places like York, Lincoln, London, Thetford and Southampton were radically transforming our knowledge of Saxon and Viking towns.

I watched all this and I freely admit I wavered, but I then decided to stay a prehistorian. Now I’m quite sure it was the right decision. But I recall one lunchtime on the first excavation at Fengate that I directed, back in 1971. In those less Health and Safety conscious days we would go to the pub for beer and sandwiches, and then – I’m now ashamed to admit this – sometimes I’d drive heavy machinery in the afternoon. Anyhow, I was standing at the bar listening to our Inspector from the Inspectorate of Ancient Monuments at the Department of the Environment, Brian Davison. He was telling us how his dig a few years previously at Thetford had thrown light on the way Saxon townspeople organised their rubbish collection.13 I almost choked on my beer. That was precisely the sort of detail I wanted to reveal about the Bronze Age. But where was I to find the evidence? For that brief moment I bitterly regretted my earlier decision. Then, as happens, the feeling wore off when I returned to site.